Twenty-three-year-old Rachel Corrie traveled to Gaza at the height of the second intifada intending to initiate a sister city project between Olympia, Washington, her home town, and Rafah as part of her senior-year project at Evergreen College. After a two-day seminar in the offices of the International Solidarity Movement in the West Bank, she continued on to Rafah to join ISM members, who were demonstrating against the Israeli military’s massive demolitions of houses on the Egyptian border. Less than two months after her arrival, on March 16, 2003, Corrie was crushed to death by a Caterpillar D9R Israeli military bulldozer.

Following the tragic event, Corrie’s family filed two lawsuits. The first was against Caterpillar Inc. The Corries claimed that the corporation was liable for Rachel’s death because it sold Israel bulldozers knowing that they would be deployed in violation of international law. The case was dismissed by a federal district judge in November 2005 for lack of jurisdiction. That same year, the family filed a civil suit in Israel against the State of Israel and the Defense Ministry. The objective of this suit was to illustrate, in Rachel’s mother’s words, “the need for accountability for thousands of lives lost, or indelibly injured, by [Israel’s] occupation…. We hope the trial will bring attention to the assault on nonviolent human rights activists (Palestinian, Israeli and international) and we hope it will underscore the fact that so many Palestinian families, harmed as deeply as ours or more, cannot access Israeli courts.”

The suit’s first testimony was heard in the Haifa district court in March 2010—the seventh anniversary of Rachel’s death—and after fifteen sessions and twenty-three witnesses, the closing remarks were heard on July 10, 2011. While the plaintiff and the defense team did not see eye to eye on the vast majority of the issues pertaining to the suit, they did agree on the basic facts: Rachel Corrie had been crushed to death by a Caterpillar military bulldozer while nonviolently protesting with fellow ISM members.

Given these indisputable facts, the central question the court then had to adjudicate was whether or not the state was responsible for Rachel’s death.

In the days leading up to the ruling, I wondered how the state was going to make the case that Corrie was to blame for her own death; I therefore read the 145-page summation submitted by the defense. The document appeared convincing at first. Indeed, if read on its own—ignoring the political context and the plaintiff’s summations and response—one might easily be persuaded that Corrie was a reckless human being who was fully responsible for her own demise.

The defense team introduced a series of arguments to persuade the court, two of which were pivotal for their case.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →The first had to do with who Rachel Corrie really was. Underlying the state’s reasoning is an Aristotelian syllogism, bolstered by photographs, graphic figures and authoritative references. The claim is straightforward:

1) the ISM is an anti-Israeli organization that supports violence and terrorism

2) Rachel Corrie was an ISM member, therefore:

3) Rachel Corrie supported violence and terrorism

The second argument was similar:

1) during the period in question, Rafah was a war zone and a closed military area

2) Rachel Corrie chose to be an activist in Rafah, therefore:

3) Rachel Corrie willfully (and illegally) subjected herself to the rules of engagement that apply in a war zone

If one accepts these conclusions and is convinced by the claim that the Caterpillar driver did not see Corrie despite the fact that she wore a brightly colored reflective vest, then it can indeed be inferred that she carries the blame for her own death.

What is amazing about the summations, however, is not their logic, but the way the state went about demonstrating its claims. Let’s consider the photographs, since they were brought forth as markers of unadulterated truth.

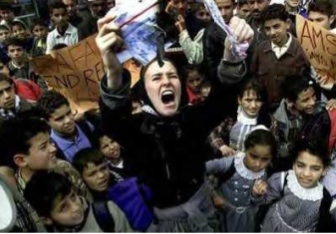

Corrie’s face is directed upwards, mouth wide open; she is screaming as she looks at a piece of burning paper held with both hands against the sky. She is portrayed here as the paradigmatic extremist whose fanatical behavior is influencing a group of young children huddled around her. The caption for this photo reads: “The deceased, Rachel Corrie, burning an American flag during a protest in Rafah.”

Directly under this photo of Rachel is a picture of four people, three of whom are holding guns and one wearing a uniform without a gun. The two standing figures appear to be foreigners, the person in uniform appears to be Palestinian, while the face of the second person sitting is intentionally blurred. (Why? We are not told) The title of this photo and of another one next to it (with several people posing in a similar manner, two with guns) reads, “Photographs of organization members holding guns, disclosed by the American journalist Lee Kaplan.”

Let’s set aside the question of whether the so-called journalist Lee Kaplan—whose claim to fame are articles he writes for the academic monitoring website IsraCampus—is trustworthy and think about what these images are meant to prove.

The fact is that we are not told where and when the two additional photos were taken, who the people in the photographs are, whether Corrie knew them or what their affiliation is. Yet this uncertainty is obscured by the placement of these suggestive photos adjacent to the one of Corrie. Through this crude juxtaposition, the state attempted to impute guilt by association.

Just a few pages earlier, the defense team offers the judge a key as to how to decipher the photos. One of the state’s expert witnesses, an Israeli reserve general—who incidentally was the IDF spokeswoman when Rachel Corrie was killed—is quoted as saying that the ISM carries out “illegal and violent” activities by “occupying terrorists’ homes to prevent their destruction, providing shelter to terrorists and terrorist operatives, taking an active part in clashes with soldiers, and serving as human shields for wanted people or for the homes of Palestinians.”

The prime incident mentioned by the state to back these accusations involved two ISM activists, who were, according to the defense, caught in the ISM offices in the West Bank city of Jenin hiding an Islamic Jihad leader who possessed a handgun and a Kalachnikov assault rifle. The Palestinian, we are told, was subsequently sentenced to thirty years in prison for terrorist activity. And yet, as the plaintiff’s attorney pointed out in his response, the absence of any record of the ISM activists being charged with “abetting a leading terrorist” or any other allegations is extremely mysterious.

A number of pages after the presentation of these images, the defense team concludes this part of the argument:

The members of the organization, including the deceased, were willing to risk their lives for the sake of advancing their agenda…. They lay down in front of weapons of war, entered fire zones where life-threatening live fire was deployed, and served as ‘human shields’ for leading terrorists in a way that endangered their lives.

The deceased also knew that the death of an American citizen would create a pronounced media/political outcry around the world, far beyond the death of a local Palestinian, in ways that would advance the organization’s agenda. Therefore, although there was mortal danger in the Gaza Strip and along the Philadelphi route in particular, the deceased chose to risk her own life, and she prepared herself in advance for this risk.

Rachel Corrie’s death, in other words, was suicide.

In order to strengthen this claim, the state also averred that Corrie illegally entered a war zone. In his response to the state’s summation, the attorney for the Corrie family, Hussein Abu Hussein, claimed that the state had failed to produce a written military decree, published by a commanding general, which would prove that the area had indeed been a closed military zone. Without a written decree, he convincingly argued, Corrie’s activities in the area cannot be considered illegal. Furthermore, he maintained that the precise meaning of the term “war zone” is disputed, and that Rafah at the time was not a war zone.

In his summation Abu Hussein mentions another line of argument. If one concedes to the defense that the area was a closed military zone and that at the time Rafah was indeed a war zone, then a crucial question emerges: Why didn’t the soldiers simply arrest Corrie, put her on a plane and send her back home?

The IDF has done this on numerous occasions with other activists. Indeed, in 1989 I was detained and held in prison for five days, together with twenty-nine other Israeli activists, for entering a closed military zone. Given that the defense team admitted that on that fateful March day before Corrie’s death, the soldiers and Corrie played a game of cat and mouse for several hours, whereby they would try to bulldoze an area and she would try to block them, detaining her does not seem like it would have been much of a problem. Indeed, if one were to accept the defense team’s narrative that Corrie was a crazy fanatic, why did the military allow her to protest illegally and unhindered?

Due to a deeply ingrained institutional bias that has been documented by law professor David Kretzmer of Hebrew University, the judge did not ask the defense team such questions. He was not disturbed by the fact that the state failed to produce a military order declaring the region a closed military zone, or by the fact that the state’s expert witness had been the IDF spokesperson at the time of Corrie’s death, or by the fact that several minutes were missing from the military tapes that recorded the incident. Nor was the judge at all disturbed by the state’s twisted presentation of the political context in which Corrie’s killing took place.

Whether or not Rafah was a war zone may be debatable, but it was clearly an arena of dangerous and often lethal confrontation. Human Rights Watch reports that during the first four years of the second intifada, the Israeli military demolished 1,600 houses in Rafah, a densely populated town and refugee camp located on the border with Egypt. Aerial photos depicting the way the terrain changed between April 2000 and December 2003 reveal the degree of destruction. As a result of these demolitions, 16,000 people—more than 10 percent of Rafah’s population—lost their homes, most of them 1948 refugees who were being dispossessed for a second or third time. Rachel Corrie came to the area to try, in her own humble way, to help these people.

“I feel a lot of horror,” Corrie said in an interview only days before her death, describing the situation as “a systematic destruction of people’s ability to survive.” She knew that joining the people of Rafah was dangerous, and she wrote to her family that she was often scared. Indeed, according to the Israeli military, between September 2000, when the second intifada erupted, and Rachel’s death in March 2003, close to 6,000 grenades were thrown at the IDF in the region, there were 1,400 shooting incidents between the IDF and Palestinians, and 150 roadside bombs were detected. Writing for Haaretz, Amira Hass reveals that bullets were fired in both directions. From August 2002 until March 2003, 101 Palestinians were killed in the region, forty-two of them children. One Israeli soldier was also killed during the same period.

The defense team used these statistics against Corrie, claiming that she put herself in harm’s way, but one could, more persuasively I think, say that she was an incredibly courageous human being who believed that all people should enjoy basic rights, such as freedom, self-determination and security. And Rachel was willing to struggle for such rights.

Haifa District Court Judge Oded Gershon showed no empathy toward this line of thinking, and on August 28 handed down his verdict: the State of Israel and the Defense Ministry were not responsible for Rachel Corrie’s death.

Tragically, the judge’s dismissive attitude mirrors the attitude of the US State Department from the time of Rachel’s killing up to the verdict. This was blatantly obvious right after the verdict, when the US ambassador to Israel noted that the IDF’s investigation was unsatisfactory. The State Department immediately retracted the statement and backed up the Israeli government. The State Department’s approach is part of a long tradition of close US-Israeli cooperation in the repression of Palestinians, which, as the Corrie case reveals, is carried out even at the expense of US citizens.

While the court did not do Rachel Corrie justice, I would like to believe that her memory can help advance her cause. Several years ago I wrote about the civil suit for The Nation, and at the time I ended the piece with Rachel’s last words to her mother. I cannot think of a better way of remaining optimistic after this terrible and unjust verdict than by invoking this brave woman’s own words once again: “I think freedom for Palestine could be an incredible source of hope to people struggling all over the world. I think it could also be an incredible inspiration to Arab people in the Middle East, who are struggling under undemocratic regimes which the US supports….”