(AP Photo/Mary Altaffer)

The recently announced merger of Penguin and Random House, which is owned by Bertelsmann in Germany, sent shock waves throughout Western publishing circles. This new leviathan will publish a quarter of all books appearing in English, with annual sales of close to $4 billion, yet it is being treated by The New York Times and other media as a routine and perhaps even beneficial development.

Since the 1980s, when Random House was purchased by Si Newhouse’s Advance Publications, mergers have swallowed up most small and independent US and British firms. Publishing has been so dominated by the major conglomerates that another merger seems natural, the Times suggests. Indeed, others can be expected to follow. Rupert Murdoch has already expressed his disappointment at not having bought Penguin and his desire to buy another large firm to merge with HarperCollins, a subsidiary of News Corporation, which his family controls.

In a way, there’s a logic to this analysis. The mergers are occurring because book publishing has proved to be less profitable than the conglomerates had hoped. For most of the past two centuries, Western houses averaged a mere 3 percent annual profit. The new owners had hoped to raise the rate closer to 25 percent, to match those of their other holdings: newspapers, magazines and TV stations (even though these depend on advertising). But try as it might, publishing failed to churn out enough bestsellers.

Then came the competition from Amazon, which has entered the publishing market itself, hiring agents and editors to help it find bestselling authors. Amazon has also forced publishers to accept its pricing of e-books at $9.99—which has drastically reduced their profit margins and has the additional benefit for Amazon of weakening sales of the traditional trade paperback, the format publishers have counted on as a dependable earner. It has even refused to list the books of houses that resisted its policies. Amazingly, the Justice Department has taken an extremely narrow view of the antitrust laws, prosecuting the publishers resisting Amazon’s pricing rather than the behemoth pressuring them.

Faced with this challenge, the newly merged companies argue that they will save money on sales and distribution, and thus compete with Amazon or get a better deal. They can hardly argue that they will publish more profitable books, since they are doing all they can now. But they can cut the smaller titles, commonly known as the midlist. The Economist quotes Mark Oliver, a publishing consultant, saying that he “expects Penguin Random House to cut the number of midlist authors, just as music labels once cut mediocre crooners.” So much for literary authors or those attempting serious nonfiction. But as every business school student knows, the real savings come not from eliminating titles but from firing those hapless editors who still feel it part of their duty to find such books.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Citing Thomas Rabe, the head of Bertelsmann, the Times tried to reassure its readers that “the merger would also allow the combined company to invest in emerging markets, which show more promise for growth than developed markets like the United States and Western Europe.” That’s not an encouraging comment about their hopes for publishing in this country. When I was in India last fall, I met the chief editors of the leading European-owned houses, who did not seem to share such expectations and indeed worried about the sales and profit targets they were expected to meet. But Bertelsmann—famous for having more accountants in its headquarters than editors in all the companies it owns—must have more accurate projections than its employees possibly could.

Let us then assume that these optimistic projections are correct: fewer titles and editors, more efficient distribution and a better deal with Amazon, at least for the larger and stronger firms. Will this suffice to please the stockholders?

We have seen in recent months an important new corporate trend. Hoping to interest Wall Street in his more promising holdings, Murdoch has decided to group his less profitable newspapers with his HarperCollins publishing empire—his “underperforming publishing assets,” as the Times calls them. This would unmoor his really profitable holdings, like Fox TV and BSkyB, from the drag of the printed word. Pearson likewise has liberated the Financial Times and the very profitable Penguin education titles from a similar contagion. It would gladly have sold off Penguin trade—the best of the British publishers and, one would have thought, the jewel in the corporate crown—were it not for the huge capital gains taxes involved. Bertelsmann apparently hopes its new merger will raise the hitherto disappointing profits it has realized from the 10,000 titles Random House publishes annually through its 200 “imprints” (once flourishing independent houses). But what these maneuvers suggest is that trade books simply aren’t profitable enough, and never will be for their corporate owners, and that the houses that publish them probably should not have been bought in the first place.

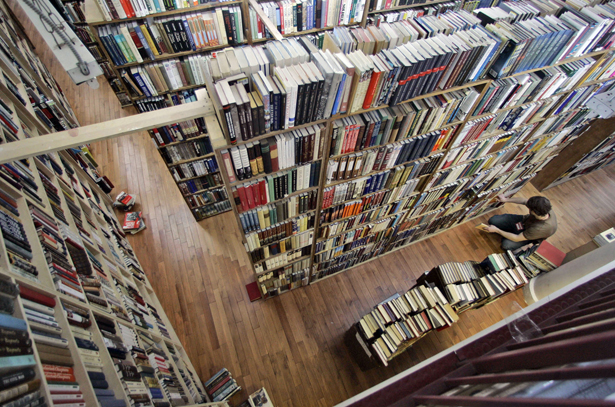

The future of books does not look good. The chains have long since succeeded in eliminating most of the independent bookstores by offering huge discounts until the competition gave up. In postwar New York, when I worked as a boy in the 8th Street Bookshop, there were 333 independents. Now there are no more than a few dozen stores overall, including chains. And even these are under increasing pressure from Amazon, which has vowed to eliminate the middlemen. With the end of Borders and declining profits for Barnes & Noble, even the chains are vulnerable. The stores that allowed readers to discover new books—and to receive advice from knowledgeable sales clerks—have largely disappeared. Amazon has not tried to fill this role, and has come to rely more and more on the publicity surrounding established bestsellers, lavishing on them full-page ads in the Times Book Review and The New Yorker. These will certainly continue to sell well in electronic format, even though the chains are beginning to fight back; there are reports that they are refusing to stock, or push, those bestsellers.

But as we can tell every week from the Times bestseller lists, the same handful of books tend to sell the best, in whatever format. The smaller titles will increasingly disappear from the catalogs of the larger firms, and the few remaining independent publishers will have even greater difficulty finding outlets for their limited production.

Again, according to the Times, agents and authors have expressed their fears and have supposedly been reassured by the conglomerate heads. But these promises are clearly meaningless. The agents will have fewer and fewer bidders, the authors fewer and fewer publishers. As for the readers, even the Times has not found a conglomerate executive willing to tell them that the future looks promising.

Amazon got big fast, hastening the arrival of digital publishing. But how big is too big? asks Steve Wasserman, in “The Amazon Effect” (June 18).