On May 15, the Federal Communications Commission voted to move forward with their proposed rules for net neutrality, the principle that all Internet traffic should be treated equally. The proposal, which will now be open for public comment for four months, would dramatically change the Internet. The new rules would allow Internet service providers (ISPs) like Verizon or AT&T to charge websites like Facebook and Twitter for faster service. This has a whole range of consequences for you, the avid Internet user. We’ve put together this explainer to help you understand what the proposal means and how you can tell the FCC what you think about the proposed rules.

What is net neutrality?

For a detailed look at what net neutrality is and the history behind legislating for an open Internet, see our earlier explainer here. As I wrote in December, the principle of net neutrality “guarantees a level playing field in which Internet users do not have to pay Internet service providers more for better access to online content, and content generators do not have to pay additional fees to ensure users can access their websites or apps.” In other words, all Internet traffic should be treated equally.

What has happened up until this point?

The history of the current proposal goes back to 2010, when the FCC issued an Open Internet Order. This created some net neutrality rules, which prohibited Internet service providers from blocking content and prioritizing certain kinds of traffic. Consumer rights advocates criticized the rules as too weak because they did not cover mobile web providers. Telecommunications companies, though, countered that the rules were too strong.

Currently, Internet service providers are legally classified as “information services,” and the law says that no discrimination or price regulations are “necessary for consumer protection.” This means that the FCC has no authority to regulate those services, though the commission does have indirect authority to regulate interstate and international communications. After the FCC released its Open Internet Order, Verizon filed a lawsuit against the FCC claiming that the commission didn’t have the authority to make those rules or enforce them over Internet service providers like itself. In January of this year, the DC Court of Appeals agreed with Verizon and said that the FCC can’t stop Internet service providers from blocking or discriminating against websites or any other Internet traffic unless the Internet is reclassified as a public utility. But the court also said the FCC does have some authority to implement net neutrality rules so far as it promotes broadband deployment across the country.

The FCC took that small window of opportunity and worked on a new proposal over the last few months. On Thursday, they voted to present the proposal to the public for comment, which is what’s on the table now. It’s called a notice of proposed rule-making.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

What is a notice of proposed rule-making?

A notice of proposed rule-making, or NPRM, is a bureaucratic term to describe an announcement that a government agency is thinking of making rules about an issue and is giving the public the opportunity to weigh in. This NPRM process happens for every government agency with some authority to make new rules. By opening up an NPRM, the FCC is saying to the country, “Hey, we’re considering this proposed rule. What do you think of it?”

What’s in the NPRM?

The entire NPRM document is ninety-nine pages and you can read it here. The FCC’s proposed rules, as previously mentioned, leave the door open for content creators to pay to get faster service. Internet service providers have been considering arrangements like this for some time. In these agreements, ISPs like Verizon or AT&T would approach companies like Netflix or Facebook and say, “We’ll give your users faster access to your website if you pay us a fee.” The proposal would create a fast lane for content creators who can afford to “pay to play,” while keeping a slower lane for sites that can’t afford to make such agreements.

In an attempt to try to balance that with the public interest, the Commission introduced three rules to keep the Internet “as an open platform enabling consumer choice, freedom of expression, end-user control, competition, and the freedom to innovate without permission.” Those three rules would require transparency about broadband providers’ practices; prohibit blocking any lawful website or app and ban “commercially unreasonable practices.”

What do these rules mean?

The transparency rule would require Internet service providers to publicly share a performance report that would include information about their Internet speed and traffic congestion, as well as any instances of blocking content or pay-for-priority agreements like the ones described above.

The no blocking rule would prohibit any Internet service company from outright blocking lawful content for any reason. This would prevent an Internet service provider from, for example, blocking the sites of their competitors.

The third rule, banning “commercially unreasonable practices,” is not as clearly defined, but it generally bans unfair business practices. FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler has said in the past that he wouldn’t accept, for example, practices that would slow down your access to a particular website if you paid for a certain Internet speed. So if you paid for high-speed Internet access and you want to read something on TheNation.com, your Internet service company can’t slow your access to DSL speeds because that would be “commercially unreasonable.”

So what are people saying about the proposal?

Consumer rights advocates like Free Press and Consumers Union argue that these rules would essentially create two tiers of Internet service, which does not amount to “real” net neutrality, which is intended to treat all Internet traffic equally. These groups have also argued that the Internet should be reclassified under the law and regulated as a public utility. The Consumers Union has argued in previous comments that public utility regulations have “protected consumers in the traditional phone marketplace and [are] appropriate for broadband Internet access.”

On the other end of the debate are Internet service companies like Verizon and AT&T who say that the FCC should regulate from afar under a less rigorous enforcement scheme. They prefer that the Internet stay under a “light-touch” regulation scheme as an information service rather than a public utility. Verizon, in a statement after the proposed rules were announced, said that utility regulation on the Internet “would lead to years of legal and regulatory uncertainty and would jeopardize investment and innovation in broadband.”

Some content providers have been quite critical of the proposal. A group of 150 companies, including Amazon, Google and Netflix, sent a letter to the FCC in May pressing the commission to ban paid prioritization for services. Some companies, including Netflix, say they might reluctantly sign on to a paid prioritization agreement with an ISP, but they do not want to pay extra just to reach their customers with quality video service. The proposal “could legalize discrimination, harming innovation and punishing US consumers with a broadband experience that’s worse than they already have,” a Netflix spokesperson said on May 15.

What happens next?

Now the public has the opportunity to submit comments to the docket—the place where people file their ideas about the proposed rules. The public has until September 10 to submit comments, but really you can submit comments until the FCC puts the rules on their meeting agenda. The FCC is supposed to take all comments into consideration, but of course heavy lobbying from all sides of the debate influences that process. That doesn’t mean your comment doesn’t matter, but just be aware it’s not necessarily a fair process.

How can I tell the FCC what I think?

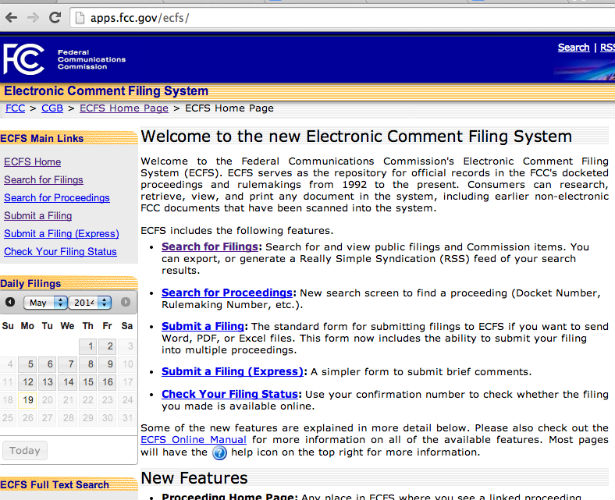

If you have access to the Internet, you can go to the FCC’s e-filing website and click ”submit a filing.”

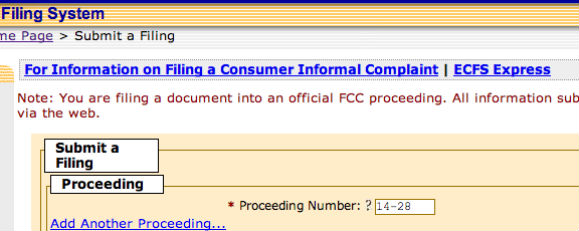

Next enter “14-28” into the proceeding number.

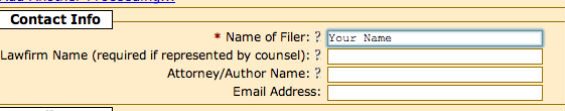

Enter your name.

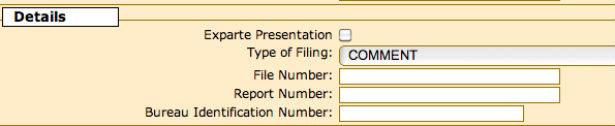

Make sure you have “comment” as the filing type under the “details” section.

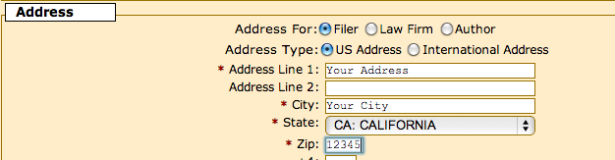

Enter your Address.

Have your comments ready to go in a Word document or text file, and then under documents, click “choose file” and upload your comments and click continue.

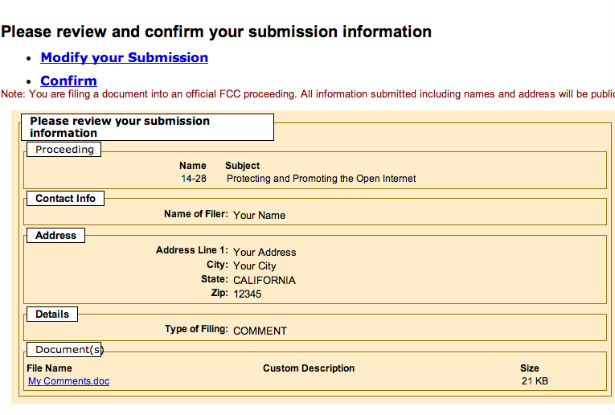

The next page is a confirmation page so you can check your information to make sure it’s correct. When everything is ready to go, press “Confirm.”

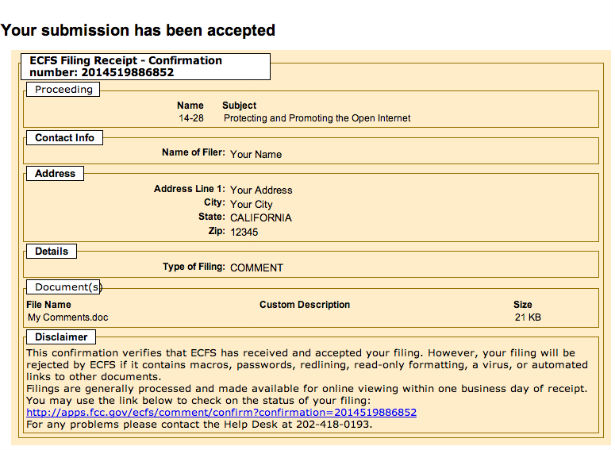

Next you’ll see a final confirmation page that your comments have been submitted.

How else can I file a comment?

You can also file by paper. You can submit your comment by hand or messenger delivery, by commercial overnight courier or by first-class or overnight US Postal Service mail. All filings must be addressed to the commission’s secretary: Office of the Secretary, Federal Communications Commission. US Postal Service first-class, Express and Priority mail should be sent to FCC Headquarters at 445 12th Street SW, Washington, DC, 20554. Commercial overnight mail must be sent to 9300 East Hampton Drive, Capitol Heights, MD, 20743.

If you want to drop off your comment, you can go to room Room TW-A325 at the FCC Headquarters address above, Monday through Friday, between 8 am–7 pm.

For people with disabilities, you can request materials in accessible formats (Braille, large print, electronic files, audio format) by sending an e-mail to [email protected]v or calling the Consumer & Governmental Affairs Bureau at 202-418-0530 (voice) or at 202-418-0432 (text telephone).

What happens after the comment period closes in September?

The FCC will review the comments and might make adjustments to its proposal based on the input they’ve received from the public and the meetings they’ve had with businesses and public interest groups. Once they’re ready to vote, they’ll put the rules on their open meeting agenda for an official vote. The FCC is expected to make their final decision by the end of the year.