Last year, Columbia students were up in arms about the sexual assault epidemic on their campus. After shocking stories of the university’s seemingly deliberate mishandling of numerous investigations and disciplinary hearings, many students went public: demonstrating on campus, covering buildings in red tape, interrupting parent orientations and posting the names of alleged rapists on bathroom walls.

In April, the school drew national media attention after students filed three federal complaints—prompting investigators to examine twenty-three separate cases regarding Columbia’s response to sexual assault and mental health needs. The complaints came on the heels of numerous federal Title IX complaints across the country leveled by students at UNC, UC Berkeley, Occidental, Dartmouth, Swarthmore, USC and Emerson College accusing their respective administrations of similar mishandlings.

Before Columbia’s campus erupted, other Columbia students had spent months negotiating with administrators for relatively uncontroversial changes like a release of anonymous aggregate data on campus assault prevalence and increased accessibility to information regarding the rape crisis response process.

Members of the college Democrats, for example, had been meeting quietly with administrators, formulating a flowchart for the university in order to clarify what rights and resources survivors were entitled to.

After four months of negotiation, university administrators agreed to publish the flowchart online, but when they did, students found that the administration had cut crucial information, including which academic and living accommodations survivors were entitled to and what evidence would be admissible at university sexual misconduct hearings.

The E-mail

On May 5, one of the students involved in negotiating the flowchart e-mailed the administrators requesting that, in future negotiations over sexual assault policies, student voices be part of the final decision-making process (The Nation obtained this e-mail exchange from another anonymous source). She wrote (emphasis added):

I would request that in the future we could have direct contact with whoever makes the decision on what information can be included or excluded. I am sure that you expressed to them which pieces of information we felt most strongly about including, but perhaps we might be able to make a stronger case for ourselves if we can communicate with them directly. Will this be possible for future projects that students might want to work on with you/other administrators?

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

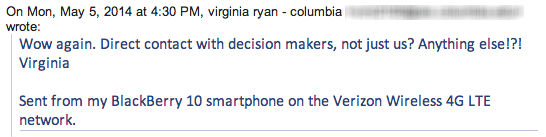

In response to the notion that students might have some say in what goes into an informational flowchart for students, Virginia Ryan, a university Title IX compliance officer accidentally sent the following e-mail, meant for her colleague Michael Dunn, Columbia’s deputy Title IX coordinator and director of investigations:

If this is the Columbia administration’s attitude toward a student request to discuss small improvements, like a flow chart, imagine their attitude toward the growing campus demand that students help overhaul Columbia’s entire treatment of and response to sexual violence. Ryan has not replied to requests for comment. In an e-mail to the student afterwards, Ryan apologized, claiming that “the tone and content” of her message was not meant to convey “intent to ‘handle’ students.”

The student’s response to Ryan’s accidental message is worth republishing in full:

Still Shut Out

Despite this embarrassing exchange and the national uproar around Columbia that has continued unabated since last year, students report to The Nation that they still feel marginalized and cut off from the school’s reform efforts.

On August 15, Columbia released its revised Gender-Based Misconduct Policy—a reform measure that, while significant, upset many students, who claim it did not take into account student voices and hence fails to address Columbia’s institutional anti-survivor bias. Two anonymous student leaders, who were notified about the updated policy three days before its release, agreed to speak to The Nation.

According to one of the students, administrators from the Office of the President and the University Senate had told students that they could participate in the policy revision process after a new executive vice president of students affairs had been hired. A few days later, a small group of student representatives were surprised when Columbia’s new special adviser to the president on sexual assault prevention and response, Suzanne Goldberg, called them in to discuss certain “developments” and then abruptly told them that the policy had been reformed without them and was set to be published later that week. “We were told to sit back and wait,” said the student. “I don’t know why they had to lie about this.”

The students who had been promised a role in the revision process were not even allowed to see the policy prior to publication. “We were told by university officials that the only students who were able to see the policy were two students on PACSA [Columbia’s Presidential Advisory Committee on Sexual Assault], who only received copies of the policy after it had been written,” said one student, who attended the meeting with Goldberg. Another added, “The two PACSA students are not survivors and they were only given three days to make little comments on a plan that they had no input in.”

In response, Goldberg argued to Newsweek that sufficient student input was achieved, despite the lack of direct student involvement, “Many of the policies’ provisions were direct responses to student concerns and suggestions raised throughout the last academic year.” Goldberg also claimed to Columbia’s student newspaper that the meeting with students was convened to inform students about the policy and move forward in cooperation: “One of my interests in having that meeting was to solicit the students’ ideas for how to best engage with the community going forward in the academic year.”

But to many students, such promises for future collaboration sound like a broken record. In response to the announcement, a coalition of anti-rape students groups issued an open letter, condemning specific administrators for their refusal to work with students:

Our goal is and always has been to work with the administration—including President Bollinger, Jeri Henry, and Melissa Rooker, who were central to the development of this policy to address these critical concerns. Instead, we have been stonewalled, misled, and deliberately excluded from the revision process. Thus far, their refusal to meaningfully engage with students and their failure to respond to our concerns has made constructive communication impossible.

The New Policy’s Anti-Survivor Bias

Columbia activists argue the administration’s refusal to accept student input has reinforced the very anti-survivor institutional bias in the reformed policy that students hoped to counteract by being at the table. An analysis of the new policy supports their concerns.

The hearing panels, for example, set up to adjudicate sexual violence accusations, are “drawn from a small group of specifically-trained University student affairs administrators.” In other words, the panel members are not necessarily legally trained, and cannot be expected to operate independent of the administration’s interests, since their jobs exist in the department responsible for managing Columbia’s student life image.

Similarly, the dean of the accused assailant’s school still decides whether to grant an accuser’s appeal, despite the fact that the dean is not present at the hearing, may have no significant legal background, and has an obvious interest in maintaining the image of the school. After consulting with Columbia’s office of Gender-Based Misconduct, the dean even possesses the power to change the sanction.

“The reforms announced by Columbia today reflect significant changes to the previous system,” explained Zoe Ridolfi-Starr, the lead complainant in this year’s Title IX filing against Columbia, “but these changes are clearly just an effort to ensure they are compliant with the recently passed Campus SaVE Act, rather than a response to the serious and urgent concerns that students have been raising for the past year.”

Starr argues that because of this refusal to collaborate with students, major elements are missing in the reform plan. These include a failure to guarantee academic and residential accommodations for survivors—decisions which are left to the discretion of Columbia officials—and a lack of clear sanctioning guidelines. Columbia has not responded to The Nation’s requests for comment.

Given the hostile sentiments revealed in the internal e-mail as well as Columbia’s numerous alleged broken promises to survivors and allies, some activists have given up on the notion that Columbia will ever work with them in good faith.

Carlene Buccino, a Columbia junior, argued that the only way to extract concessions from the university would be to disrupt the school, financially and organizationally. “Nothing so far has done anything.… It’s going take a lack of money, like no donations or funding, or some type of major protest, ’68 style. Otherwise they just don’t give a damn.”

“Clearly the administration is doing everything in its power to shut us down,” said Michela Weihl, an activist, part of Columbia’s anti-rape group No Red Tape. “So we’re going to have to find other ways to threaten what they actually care about to get what we actually need.”