How Immigration Transformed Europe’s Most Conservative Capital

Madrid has changed greatly since 1975, at once opening itself to immigrants from Latin America while also doubling down on conservative politics.

The skyline of Madrid seen during twilight from the roof top of the Riu Plaza Madrid, 2019.

(Jörg Schüler / Getty Images)At the end of 2024, Spain’s National Institute for Statistics published a revealing figure: the number of Latin American–born residents in the Madrid region had, for the first time, surpassed 1 million—1,038,671, to be exact, or about 15 percent of the total population. Today, more Latin Americans live in Madrid than in Santiago (Cuba), Arequipa (Peru), or Valparaíso (Chile). This is all the more remarkable given that just a quarter-century ago, Madrid’s Latin American–born population barely surpassed 80,000.

Books in review

Madrid: A New Biography

Buy this bookFor anyone who has spent time in Madrid in recent years, however, these statistics will not come as a surprise. If you wander around the city’s northern district of Tetuán, near the Alvarado metro station, you’ll find yourself in Little Santo Domingo, a compact arrangement of streets lined with hairdressers, grocery stands, cell phone shops, clothing stores, and restaurants catering to the neighborhood’s large population of Dominicans, many of whom are already second-generation Spanish citizens. Take the metro from Alvarado some 14 stops south and you’ll arrive at Puente de Vallecas, on the far side of the Manzanares River, another corner of the so-called Latin American triangle. The district, which houses tens of thousands of working-class families of Colombian, Peruvian, and Venezuelan origin, is also home to the 100-year-old football club Rayo Vallecano. Shortly after Rayo signed Colombian stars like Radamel Falcao and James Rodríguez several years ago, a wave of yellow jerseys began washing over the stands of the Vallecas soccer stadium, representing the Colombian national team colors, drowning out the red-and-white of Rayo’s famous thunderbolt jersey—itself reminiscent of the Peruvian national team kit.

None of this existed before 1998. During the decades following the death of Spain’s dictator Francisco Franco in 1975, most madrileños from Latin America were political exiles. From well-to-do families, and often of Spanish or European descent, they had arrived in the capital fleeing the regimes in Cuba, Argentina, Uruguay, and Chile. After 1998, this mostly Southern Cone bourgeoisie was joined by working-class immigrants from Colombia, Peru, and, most significantly, Ecuador. Many of them were shuffled into domestic work, the service industry, construction, and agriculture—sectors that, given their place-bound nature, couldn’t offshore their low-wage work. These new immigrants, who were fleeing a different kind of oppression—poverty—saw the Spanish state, as the scholar Araceli Masterson-Algar has written, not as the loving madre patria (the colonial motherland) but as a stingy stepmother, a madrastra.

The most recent wave of Latin American immigrants has received a warmer welcome, especially from the region’s right-wing government. Madrid has become a new Miami for a wave of new-money arrivals from Mexico, Venezuela, and elsewhere. So much so, in fact, that part of the wealthy neighborhood of Salamanca, where people took to the streets on January 3 to celebrate the capture of Nicolás Maduro, is today known as Little Caracas. What attracts these moneyed migrants, in addition to the language, are the economic policies of Isabel Díaz Ayuso, the regional president and informal leader of the far-right flank of the conservative Partido Popular (PP). In recent years, Díaz Ayuso has managed to turn Madrid into a regional tax haven, offering some of the highest earners tax brackets in the low single digits, while cutting back on social services for the most needy populations. Her romance with the Latin American right is ideological as well: Making Latin America great again, she has suggested, requires a return to the values of the Spanish empire, and this high-powered class of Latin American conservatives are her allies in beating back the left in the former colonies. Piggy-backing on this idea, the Spanish far-right party Vox has been hosting the world’s far-right leaders in Madrid, hoping to put it on the map as the hinge between Latin American and European versions of Trumpism.

In a way, the city’s Latin Americanization is nothing new. According to the Australian writer Luke Stegemann, whose sprawling Madrid: A New Biography stretches from the Iron Age to the present, Madrid was “always a town of immigrants.” The idea of Madrid as a city of immigrants is a direct challenge to its stereotype as a proudly Spanish capital, known for its corridas de toros and aristocratically anointed soccer club Real Madrid. Stegemann wants to argue instead that the city’s greatness—culturally and politically—stems from centuries of tolerance, welcoming newcomers from elsewhere in Europe, North Africa, the Middle East and beyond. But is this how most newcomers have experienced the city? Or is it how most of the city’s leaders since 1975 would like it to be imagined?

Madrid famously owes its status as the capital of Spain to its topography, sitting as it does at the dead center of the Iberian Peninsula, squeezed between the Guadarrama mountains to the north and the Tajo River to the south. The land on which the city rests was perhaps an unusual location for early hunters and gatherers to occupy, Stegemann writes. Less protected by mountains than Toledo—the previous official capital from 1519 to 1561, but the unofficial capital of Castile since the 11th century—and far from any major waterway that leads to the sea, the city has nonetheless “been built over one of the richest archeological zones of the peninsula.” Sizable settlements in the location date to the eighth century. By the second half of the ninth century, Muhammad I of Córdoba would erect a fortress there, one of many he would build with the goal of protecting Toledo, located 50 miles to the south. This explains why Madrid, as Stegemann points out, “is the only European capital with an Islamic origin and…the only European capital with an Arabic name.”

In its premodern infancy, the city attracted travelers from all across the Mediterranean—not only North Africa and the Mediterranean islands of Malta, Sicily, and Sardinia, but also Greece, Lebanon, Egypt, and Syria. Many of these travelers eventually stayed. “The native and the foreign were blended, as ever,” Stegemann writes, “until ‘native’ itself became a densely patterned identity with multiple origins. From its very earliest times, the Iberian Peninsula was a mosaic of settlements, peoples, traditions, alliances, lifestyles, technologies, cults and rituals, and its capital city continues to bear witness to this magnificent diversity.” Since May 1561, when King Philip II handpicked Madrid to become the Spanish capital practically overnight, using it as the administrative hub of his rapidly expanding empire, scores of new migrants made their way to the city, increasing its effervescent heterogeneity as well as the richness of its culture.

In Stegemann’s account, the idea that Madrid is a city of immigrants becomes a refrain to bolster the image of a “beautiful” town that, he believes, has long been misunderstood and unfairly maligned as “a graceless city of reactionary generals and slow-moving civil servants.” “For centuries,” he writes at the book’s outset, the city “has attracted and retained citizens from around the peninsula, their multiple backgrounds and traditions all finding a home in the capital.” Throughout the book’s more than two dozen chapters, the phrase “everyone is welcome” affixes itself, like a plaque, to various plazas, parks, and other places.

This is a rather generous portrait of a city that, for centuries, was often hostile to the millions of people who were forced to resettle there in search of economic opportunity. In an article from 1835, Mariano José de Larra, one of Spain’s most important Romantic writers and one of Madrid’s most perceptive journalists, described the unstable working conditions of the waves of new migrants from elsewhere in Spain. “The same people who, in November, sell hems or braided slippers,” he observed, “in July sell horchata; in the summer, serve as lifeguards along the Manzanares River, in the winter as itinerant coffee sellers.” Larra’s article was aptly titled “Ways of Living That Are Not Enough to Live On.” (Larra, an afrancesado, or Francophile Spaniard, whose liberal satire was sharply critical of the city, is mentioned only once in Stegemann’s book.)

Two centuries later, the trend Larra described continues. Madrid’s precarious migrant workers feature prominently in Dispossession and Dissent, Sophie Gonick’s 2021 book on immigrants and the struggle for housing in the Spanish city. There’s Yvette, who “had seven jobs at once,” making a part-time salary of €300 a month with one job and supplementing that salary with the other six. There’s Morton, whose unusable law degree from Ecuador meant that he had to scrounge for whatever job he could find, “wherever there were possibilities to generate [enough] resources to be able to maintain the family back home.” And there’s Mabel, who summarized her work life—as well as that of thousands of fellow immigrants in the city—in one sentence: “Out of twenty-four hours in a day, we worked twenty.”

The situation has worsened significantly in the last few years. The housing crisis that affects all of Spain’s major cities is particularly serious in Madrid, where rents increased by close to 20 percent in 2024 alone. Since October of last year, the city has seen two massive demonstrations calling for affordable housing. As the richest region in Spain with the lowest percentage of social spending, Madrid has seen its poverty rates skyrocket: More than 8 percent of the population now lives in extreme poverty.

Inequality in Madrid is also nothing new. Stegemann connects the shanty towns that shot up on the edges of the city in the 1950s, when Franco was in power, with the living conditions of the urban poor in the late 19th century, described in detail by the novelist Benito Pérez Galdós. “Loneliness frightens me,” says the working-class protagonist of Galdós’s 1884 novel Torment. “Here,” in the city center, “seeing your next-door neighbor so close that you can shake their hand makes it feel like you live together.… When I hear about the families who have gone to live in that neighborhood, to that cemetery [José de] Salamanca is building beyond the Plaza de Toros, I get goosebumps.” Although Stegemann dedicates many pages to Galdós, he differs from him in using novelistic descriptions to hold the poor at arm’s length. Stegemann’s urban history spends little time discussing the perspective of the city these other residents might have had.

Despite frequent references to the idea of Madrid as a city of immigrants, the topic of immigration itself doesn’t occupy much space in the book. To be sure, the major demographic shifts that led immigrants from Latin America, China, and elsewhere to Spain began less than 30 years ago. But Stegemann’s lack of interest in immigrants is balanced by his fascination with those at the opposite end of the social ladder. Madrid is a book about power and those who have it.

Stegemann’s greatest-hits version of the city’s history, from Velázquez and Goya to the revolt against Napoleon and the Spanish Civil War, ticks back and forth like a metronome between two competing ideas: Madrid as an open, welcoming, and cosmopolitan metropolis befitting the grandest ideals of contemporary Europe, and Madrid as the Spanish castizo Castilian and the “proudly autonomous,” unshakable seat of monarchical, imperial, economic, and political power. One of the problems with the book is that it wants to tell a story about the first idea using historical resources that only support the second.

Another problem is that the book avoids reflecting on perhaps the greatest tension at the heart of its subject: What price has Madrid, as a city, paid for its status as Madrid, the Spanish capital? The two have long been synonymous with each other, but they need not be—and, for several hundred years, were not. What history might be told if we separated the center of political power from a city inhabited by people far removed from that power?

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Distinguishing Madrid the city from Madrid the capital is key to understanding why it is the most politically conservative capital in Europe. But doing so would require bringing economic and social history to the table. It would also require talking about the city’s most successful political party of the past 30 years, the Partido Popular, which, remarkably, goes unmentioned throughout Stegemann’s book. Since 1995, the PP has, thanks to Díaz Ayuso and two of her predecessors, Esperanza Aguirre and Alberto Ruiz-Gallardón, transformed the capital through various kinds of privatization schemes, turning much of the city outside the M-30 beltway into a space fit for an individualized, bourgeois, and seemingly accessible American lifestyle: cheap, single-family apartments with a small garage and the option to buy. Today, the rents in these suburbs are skyrocketing, and longtime residents are moving farther and farther away from the city. The reason, as The New York Times reported in April, is that the largest landlords in Madrid are now US investment firms such as Blackstone, Cerberus, and Lone Star, having acquired and raised rents on apartments all across the city and in many of its suburbs. Stegemann’s genealogy of present-day Madrid wants to convince us that the city does not deserve its bad rap. Yet the closer he gets to the present, the more he shies away from politics, as if speaking openly about the PP’s 30-year effort to create a city of property owners instead of renters somehow cheapens a narrative that is meant to be timeless.

A more honest history of Madrid would have seen the city for what it is—not just its positive or negative aspects but as a place that is in flux, filled with struggles over housing, migration, and (lately) the energy grid. Madrid matters not only because it remains the seat of Spain’s central government, which is able to suspend the right to self-government for any of the country’s 17 autonomous regions (as it did with Catalonia in 2017). It matters because it often prefigures changes that later sweep across the rest of the country. The push for sexual and cultural openness that drove La movida madrileña in the early 1980s, for instance—the moment that launched the career of Pedro Almodóvar—paved the way for Spain’s becoming, in 2005, the third country in the world to legalize same-sex marriage. A more engaging history of Madrid would not have limited itself to celebrating political moments and cultural achievements as so many trophies in a display case. Instead, it would have looked at those moments and achievements to understand what they might tell us about Spain’s future.

More from The Nation

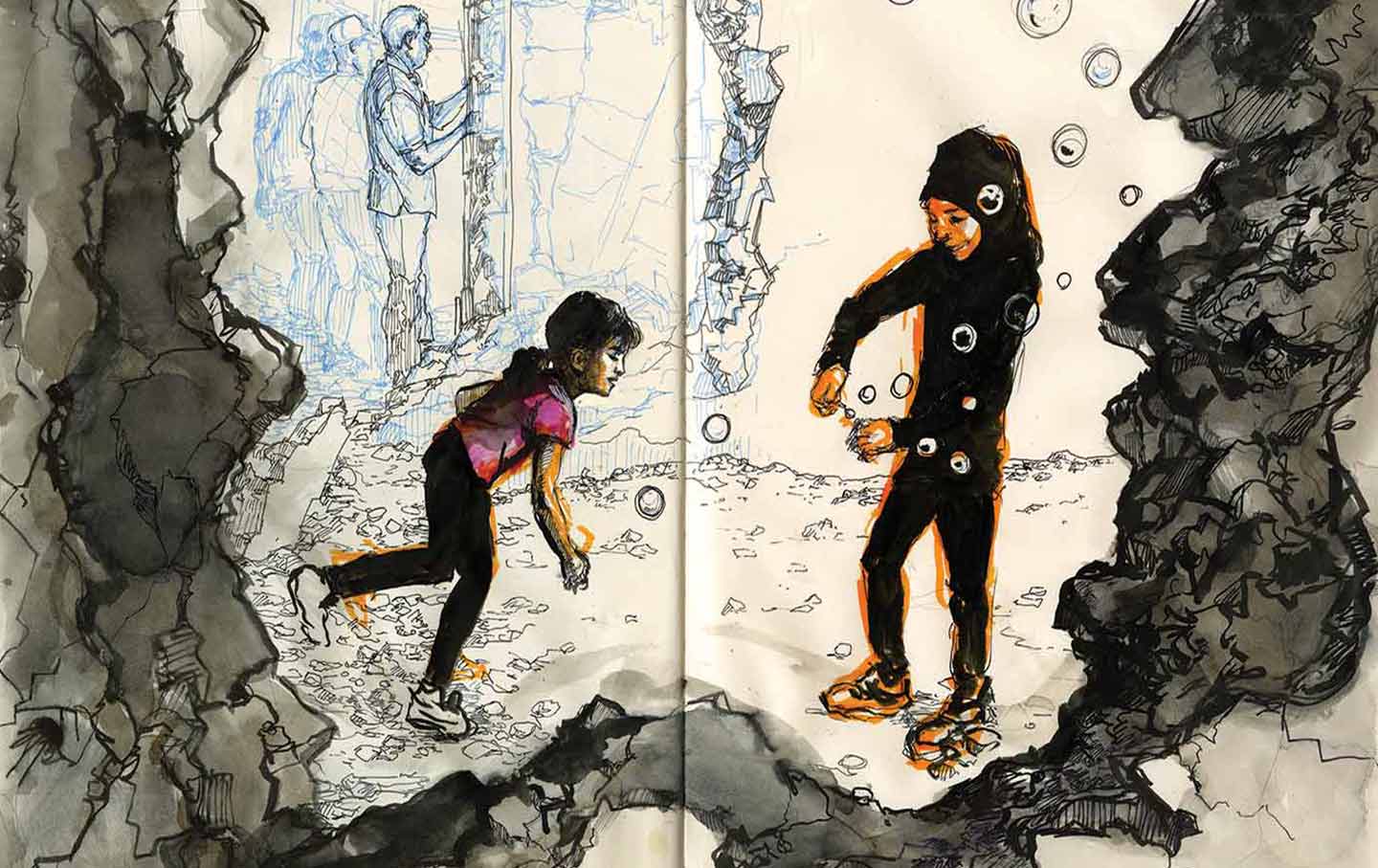

Molly Crabapple's Time Capsule of Resistance Molly Crabapple's Time Capsule of Resistance

A new set of note cards by the artist and writer documents scenes of protest in the 21st century.

The Exposure Therapy of “A Private Life” The Exposure Therapy of “A Private Life”

In her new film, Jodie Foster transforms into a therapist-detective.

How to Build a Moon Garden When the News Is All Horror How to Build a Moon Garden When the News Is All Horror

The Riotous Worlds of Thomas Pynchon The Riotous Worlds of Thomas Pynchon

From “The Crying Lot of 49” to his latest noirs, the American novelist has always proceeded along a track strangely parallel to our own.

Letters From the March 2026 Issue Letters From the March 2026 Issue

Basement books… Kate Wagner replies… Reading Pirandello (online only)… Gus O’Connor replies…