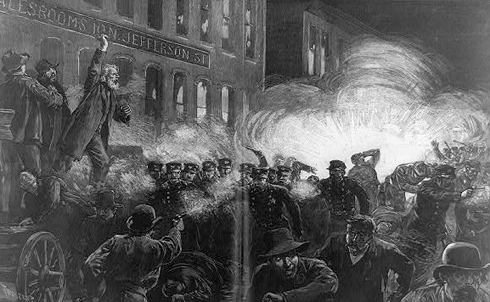

What began as a rally in support of striking workers and the push for an eight-hour workday quickly turned into one of the worst police massacres in American history when a bomb was hurled at police officers dispersing the crowd in Chicago’s Haymarket Square on May 4, 1886. The explosion and the melee that ensued as the police opened fire resulted in the deaths of eight police officers and an unknown number of civilian deaths.

In the show trial following the massacre, eight rally organizers were charged with the murder of the police officer killed by the bomb, even though prosecutors admitted that none of the men had actually thrown the explosive device. All eight were convicted of the crime they did not commit, and on the night before four of them were hanged, The Nation reported that two thousand people walked down Broadway in New York “bearing red flags and black banners inscribed with incendiary sentiments.” After the executions, a funeral procession through the streets of Chicago wore red ribbons and sung the Marseillaise.

Out of this travesty of justice arose the International Workers’ Day and the progressive tradition of May Day as we know it today. In the decades since the massacre, the workers’ movement has won a host of government reforms, union advances and a political approach that eliminated some of the worst horrors associated with industrialization. To mark this tragic event, but also to celebrate the great victories that came in its wake, we have assembled a collection of articles and images from The Nation’s archives in the following slides. It’s a very incomplete but, we hope, inspiring collection of some of the highlights of US labor history over the last 100 years.

Credit: Harper’s Weekly / Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

One century ago this year, on March 25, 1911, an infamous fire spread through the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York City’s Greenwich Village, killing 146 mostly female workers who were trapped on the building’s upper floors. As Joshua Freeman explains, the tragic fire captured the country’s attention in a way that no industrial disaster ever has before or since, but not only for the scale of destruction or loss of life. The fire remains such a touchstone for the American labor movement because it fulfilled “a deeply held belief, or at least a yearning to believe, that good can come out of suffering, that death does not have to be in vain" and because it led to far-reaching changes in factory regulations on safety.

Credit: Brown Brothers, 1911 / International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union Archives, Kheel Center, Cornell University

1909 saw the first mass-action of women workers in the US as tens of thousands of garment workers followed their colleagues at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in walking off their sweatshop jobs, demanding safer workplace conditions and the right to unionize. Over the eleven-week-long “Uprising of the Twenty Thousand,” as the strike came to be known, the immigrant workers were locked out of their jobs, arrested, beaten and spat on for being “on strike against God.”

But, courageously led by Clara Lemlich and the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, the workers ultimately won significant victories, as most of the garment factories became union shops and the industry workweek was capped at 52 hours.

Credit: George Grantham Bain Collection / Library of Congress

Significantly, one the factories that was not unionized during the uprising was the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, and a mere two years after the strike, the factory’s shoddy conditions led to disaster. A fire broke out on the eighth floor of the building near the end of the workday on March 25, 1911, and with doors locked to prevent stealing and early release, inadequate fire exits and shop floors laden with flammable materials, the flames quickly spread to the ninth and tenth floors. Desperate women, children and men trapped in the inferno were forced to choose between being burned alive or jumping to their deaths on the streets below.

The fire killed 146 workers, and more than 100,000 mourners turned out for their funeral procession. The tragedy became a turning point for labor organizing and for workplace safety: a report released a year later outlined specific policy changes for regulating manufacturing in tenements and employment of women and children. As reported in The Nation, the fire could have been easily prevented, and the failure stands as a shameful “lack of proper exercise of the police power of the State in safeguarding the lives of industrial workers.”

Credit: George Grantham Bain Collection / Library of Congress

After World War I, high inflation made it difficult for poorly-paid industrial workers to survive. In 1919, the unrest reached fever-pitch as steel workers across the country, mainly immigrants, struck against the United States Steel Corporation. Other workers steadily joined on as the “great steel strike” grew to more than 350,000.

After three months, government officials called in the National Guard and federal troops to violently quell the strike in many cities. Employers also incited a red scare by framing the immigrant protesters as foreign instigators of radical ideas. As George Soule wrote at the time, the strike was considered a failure, and led many to wonder whether the trade-union movement was “fitted to carry out their responsibility to the workers in the matter of leading and winning” their members’ struggle for greater workplace rights.

Credit: National Photo Company Collection / Library of Congress

With industrialization, children began whiling away long hours on factory floors or in garret workshops in low-paid jobs. But the labor movement pushed for protections for child workers, and forced the creation of the National Child Labor Committee in 1904. In 1913, The Nation wrote that “child-labor legislation is “spreading over the country with a rapidity greater than its most sanguine advocates could have expected a few years ago.” But it wasn’t until the Great Depression, when desperation became so enveloping that adults began accepting the same wages as children, that child labor effectively ended.

Credit: Lewis Wickes Hine / Library of Congress

The cause that mobilized the Haymarket protesters, New York garment makers and thousands of other workers in the nineteenth and early-twentieth century can be simply summed up in the slogan of the old labor song: “eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, eight hours for what we will.” What seems standard today was, in fact, a radical demand of labor’s early days—and in one of this magazine’s less enlightened moments, the editors went so far as to ridicule the “eight-hour delusion” as a “movement for growing rich faster by working less.”

It took decades of organizing and countless strikes, negotiations and shows of worker strength, but 1938’s Fair Labor Standards Act regulated child labor and instituted the eight-hour workday for the American workforce. This hard-won victory should not be taken for granted, but the ways in which the workplace has evolved over the past decades have done much to undercut the eight-hour day: in 2007, Steve Early and Suzanne Gordon explained that Americans spend far more time on the job than workers in any other advanced capitalist country, “whether unionized or not, most lack the legal protection necessary to resist forced overtime and ‘nonstandard’ shifts.”

Credit: New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection / Library of Congress

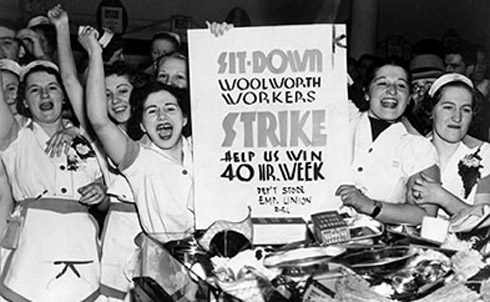

In a few short months in 1936 and 1937, the United Automobile Workers of America, transformed from a union of 30,000 into a “seasoned fighting organization of 400,000 members and in the process piled up some 400 contracts.” The union had taken on the giant and secretive General Motors by organizing a dramatic sit-down strike in the company’s factory in Flint, Michigan. Besieged by police and a ruthless management, the Flint strikers occupied their factory for weeks, refusing to leave despite tear gas and threats of violence.

During the strike, a General Motors stockholder went to visit the strikers on the factory floor, and described the workers’ grievances for The Nation’s readers: “I bought my shares at long odds and probably have already collected the purchase price in dividends,” he said. “When I place a winning bet in a horse race I do not claim a share in ownership of the horse. I know from my political economy that my position is the result of labor and sacrifice. Whose? Not mine.”

Credit: AP Photo / Library of Congress

Held to account by a powerful union movement and early civil rights leaders such as A. Philip Randolph, President Franklin Roosevelt’s administration facilitated major advances for labor and for workplace equality. In 1941, Roosevelt created the Fair Employment Practice Commission, which forbid discrimination based on race, religion, or national origin in defense industries.

Though Roosevelt’s action fell short of a full integration of the armed forces, it spurred a series of states to adopt their own commissions. “Not since the Civil War,” The Nation’s Will Maslow said in 1945, “has there been so much local interest in preventing racial or religious discrimination in employment.”

Credit: Farm Security Administration, Office of War Information Photograph Collection / Library of Congress

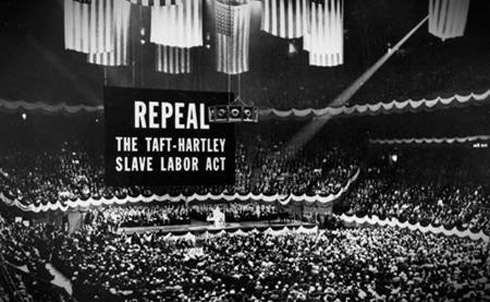

These gains were quickly tempered in the post-war period’s McCarthyist and anti-union atmosphere. 1947’s Taft-Hartley Act, passed over President Truman’s veto, severely restricted the power of unions and the actions labor could take in its defense. The American Federation of Labor (AFL), Congress of Industrial Organizations, and independent unions branded the act a slave-labor law, and The Nation’s Samuel H. Cohen reported that it “not only hampered union growth by checking the normal rate of new organization, especially in the rapidly growing industries of the South, but softened union bargaining demands by making Taft-Hartley procedures available to employers.”

The Taft-Hartley Act and similar anti-union legislation of the late-1940s were designed to slow labor’s growth, but by the middle of the next decade, the proportion of the workplace organized into unions nevertheless hit its historic high of over 30 percent. In 1955, to build on labor’s forward momentum, the Congress of Industrial Organizations merged with the American Federation of Labor to create the AFL-CIO. This brought some 160, 000 workers together into the largest federation of organized labor in the US.

The unions’ leaders deemed the move a necessary, progressive step to put craft and industrial unionism on the same level, “but the ambivalence of the men who would have to make this unity work… was symptomatic that what had taken place was a wedding without love.”

Credit: AP Images

From December 1962 until the end of March 1963, the American Newspaper Guild led the newspaper industry on its longest strike ever, with the nine affected newspapers losing over $100 million. The guild, as John Scribner wrote in 1934, provided a fundamental pubic service by helping readers determine whether papers were published in the public interest. “Few will be fooled by a newspaper that professes liberal editorial policies but deals with the guild in a reactionary manner,” he explained.

During the strike, in 1962, Donald Paneth and Herbert Shuldiner wrote that “wild-cat walkouts, closings, one-paper cities have emerged as a staple of the American scene.”

Credit: AP Images

Building on his experiences as a farmworker and community organizer in the barrios of Oakland and Los Angeles, Chavez did what many thought impossible—organize the most vulnerable Americans, immigrant farmworkers, into a successful union, improving conditions for California’s lettuce and grape pickers. Founded in 1960s, the United Farm Workers pioneered the use of consumer boycotts, enlisting other unions, churches and students to join in a nationwide boycott of nonunion grapes, wine and lettuce. Chavez led demonstrations, voter registration drives, fasts, boycotts and other nonviolent protests to gain public support. Though Chavez is an increasingly controversial figure among progressives with critics indicting him for a dictatorial manner and anti-democratic-tendencies, the UFW inspired and trained several generations of organizers who remain active in today’s progressive movement.

Credit: AP Images

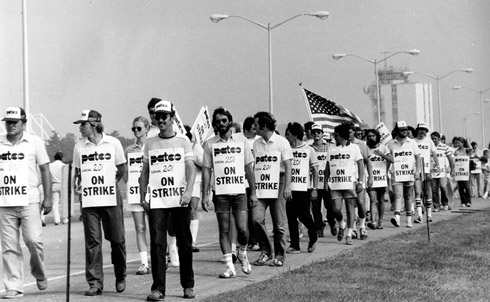

The Taft-Hartley Act came back to haunt American labor in 1981 when President Ronald Reagan claimed that the striking Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) union was in violation of the act’s prohibition against such actions by government workers. After ordering all air traffic controllers back to work within 48 hours, Reagan fired more than 11,000 workers who had disobeyed his order, and barred them from federal service for life.

John Dunlop, who had served as secretary of labor under President Ford, argued after Reagan’s radical action that “What is absolutely without precedent, at least in modern times, is that [the Reagan Administration] has brought in no outside, dispassionate group to look at the problem. That ain’t right. Also, the Administration has decided… to leave no avenue of escape for the union. You just don’t do that.”

Credit: AP Images

In the face of tremendous opposition from organized labor, President Bill Clinton signed the North American Free Trade Agreement, creating a trilateral trade agreement in North America between the US, Canada and Mexico. As Jeff Faux reported, NAFTA represented “the constitution of an emerging continental economy that recognizes one citizen—the business corporation.”

Coupled with this leap towards neo-liberalization, Faux explained, NAFTA wrote protections for workers, the environment and the public out of the picture, despite the fact that such checks on business’s power had been “part of the social contract established through long political struggle in each of these countries.”

Credit: AP Images

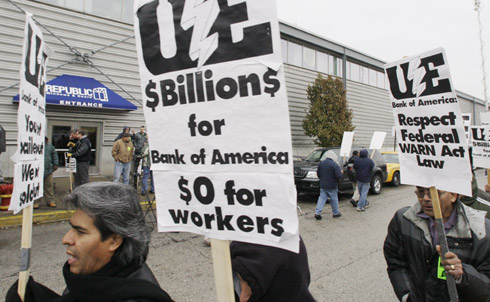

When employers started laying off workers to save their own skin as the economy took a turn for the worse in the late 2000s, embattled employees were left to fend for themselves. In one of the more egregious cases, after Bank of America refused to extend operating credit to Republic Windows & Doors in 2008, a Chicago-based manufacturer, the firm disregarded federal rules that require sixty days notice of a plant closing and announced that its factory would be closing the plant immediately.

In the tradition of the UAW’s actions in Flint over sixty years before, members of the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America responded by holding a sit-down strike. Their actions earned headlines, solidarity support from other unions, an endorsement from President-elect Barack Obama and commitments by the bank and the company to pay the displaced workers what they were owed. The Rev. Jesse Jackson likened the union members to Rosa Parks and described their actions as “the beginning of a larger movement for mass action to resist economic violence.”

Credit: AP Images

While US sweatshops in the early twentieth remain a stain on US history, the reality is that in America we haven’t completely rid ourselves of them. Robert Scheer recalls in The Nation the release of Thai slave workers at a garment factory in El Monte, California in 1995. The slaves had been held in a prison sweatshop, not allowed to leave the compound for years, making $2 an hour.

Scheer writes that the circumstances for the El Monte slave laborers were not a huge departure from the appalling conditions he had witnessed on other federal and state agency raids of California garment factories. The sweatshops predominantly employ Asian and Latin American immigrants “whose status as fugitive workers meant that, de facto, they did not enjoy the standard protections provided by labor, occupational safety and health laws.” The desperation of these laborers leave them at the mercy of their employers, and many arrive in global smuggling operations charging immense sums that take years to pay off.

Credit: AP Images

Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker’s attack on his state’s unions this spring thrust labor back into the spotlight for many Americans, and underscored that many of the lessons we thought we had learned from the Triangle Fire need to be relearned. Thousands of workers die every year on the job, and tens of thousands more die from occupational diseases. Large segments of the labor force remain almost entirely un-organized, and undocumented immigrants continue to operate in a legal limbo that makes them ripe for employer exploitation. All a reminder, writes AFL-CIO’s Tula Connell, that the "Triangle fire, a symbol of Gilded Age greed, still stands burning before us." Read Connell’s piece detailing the challenges facing organized labor, and offering resources you can use to protect your own workplace rights.

Research for this slide show provided by Sara Jerving

Credit: AP Images