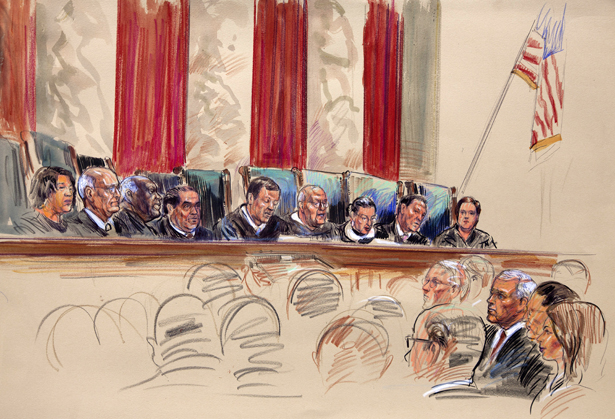

An artist rendering shows Chief Justice John Roberts, center, speaking at the Supreme Court in Washington, Thursday, June 28, 2012. From left are, Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Stephen Breyer, Clarence Thomas, Antonin Scalia, Roberts, Anthony Kennedy, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Elena Kagan. (AP Photo/Dana Verkouteren)

The Supreme Court closed out its 2011–12 term today in dramatic fashion, upholding the Affordable Care Act by a sharply divided vote. The Court’s bottom line, reasoning and lineup of justices all came as a shock to many. While I had earlier cautioned doomsayers that the law was “not dead yet” after an oral argument that others deemed disastrous for the law’s defenders, I don’t think anyone predicted that the law would be upheld without the support of Justice Anthony Kennedy, almost always the Court’s crucial swing vote. And while most of the legal debate focused on Congress’s power under the Commerce Clause, the Court ultimately upheld the law as an exercise of the taxing power—even though President Obama famously claimed that the law was not a tax. The most surprising thing of all, though, is that in the end, this ultraconservative Court decided the case, much as it did in many other cases this term, by siding with the liberals.

Justice Kennedy, on whom virtually all hope for a decision upholding the law rested, voted with Antonin Scalia, Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas. They would have invalidated all 900 pages of the law—even though the challengers had directly attacked only two of the law’s hundreds of provisions. But Chief Justice John Roberts sided with Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor, Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan to uphold the law as a valid exercise of Congress’s power to tax.

The Individual Mandate As a Tax

What led Roberts to cast his lot with the law’s supporters? The argument that the taxing power supported the individual mandate was a strong one. The mandate provides that those who can afford to buy healthcare insurance must do so, but the only consequence of not doing so is the payment of a tax penalty. The Constitution gives Congress broad power to raise taxes “for the general welfare,” which means Congress need not point to some other enumerated power to justify a tax. (By contrast, if Congress seeks to regulate conduct by imposing criminal or civil sanctions, it must point to one of the Constitution’s affirmative grants of power—such as the Commerce Clause, the immigration power, or the power to raise and regulate the military.)

The law’s challengers—and the Court’s dissenters—rejected the characterization of the law as a tax. They noted that it was labeled a “penalty,” not a tax; that it was designed to encourage people to buy health insurance, not to raise revenue; and that Obama himself had rejected claims that the law was a tax when it was being considered by Congress. But Roberts said the question is a functional one, not a matter of labels. Because the law in fact would raise revenue, imposed no sanction other than a tax and was calculated and collected by the IRS as part of the income tax, the Court treated it as a tax and upheld the law.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Chief Justice Roberts did go on to say (for himself, but not for the Court’s majority) that he thought the law was not justified by the Commerce Clause or the Necessary and Proper Clause, because rather than regulating existing economic activity it compelled people to enter into commerce. When one adds the dissenting justices, there were five votes on the Court for this restrictive view of the Commerce Clause. But that is not binding, because the law was upheld on other grounds. And while some have termed this a major restriction on Commerce Clause power, it is not clear that it will have significant impact going forward, as the individual mandate was the first and only time in over 200 years that Congress had in fact sought to compel people to engage in commerce. It’s just not a common way of regulating, so the fact that five justices think it’s an unconstitutional way of regulating is not likely to have much real-world significance.

Limiting the Medicaid Expansion

The other provision challenged conditioned state’s receipt of Medicaid funding on their implementation of the Act’s greatly expanded Medicaid coverage. Where Medicaid initially covered only several discrete categories of persons, under the ACA it extends to all adults earning less than 133 percent of the poverty level. The states argued that threatening them with loss of all their Medicaid funding was a coercive condition on the funding. Seven members of the Court agreed that if the law were enforced to take away state’s existing Medicaid funds it would be unconstitutional, but the majority upheld the provision as a condition only on the funds provided for the expanded Medicaid program. It seems unlikely that states will turn down those funds. Under the ACA, the federal government initially covers 100 percent of all new Medicaid costs, and while the federal contribution diminishes over time, it never falls below 90 percent of the program’s cost, so any rational state will likely take the money and expand its coverage.

All in all, then, the decision marks a major victory for President Obama and the backers of health insurance reform. As many Nation readers know, a single-payer system would have been much better, and the ACA is far from perfect, but the question here was not whether this was the best of all possible policies but only whether the Court would strike down the best healthcare insurance program that Congress could realistically enact. As Roberts put it, “We do not consider whether the Act embodies sound policies. That judgment is entrusted to the Nation’s elected leaders. We ask only whether Congress has the power under the Constitution to enact the challenged provisions.”

So why did Roberts do it? In part, the outcome reflects the fact that the truly radical position in this dispute was that of the challengers. Even very conservative lower court judges, including Jeffrey Sutton of the Sixth Circuit and Laurence Silberman of the DC Circuit, had concluded that the law was valid (although on Commerce Clause, not taxing power, grounds). But in addition, I cannot but think that at the back of Roberts’s mind was the Court’s institutional standing. Had the law been struck down on “party lines,” the Court’s reputation would be seriously undermined. In May, the Pew Research Center reported that favorable views of the Supreme Court as an institution had reached an all-time low. Sharply divided partisan decisions like Bush v. Gore and Citizens United appear to have done damage to the Court’s legitimacy—and ultimately, its legitimacy is the source of the Court’s power. Today’s result, which upholds the actions of the democratically elected branches on a major piece of social welfare legislation that affects us all against a challenge that was always a real long shot, driven more by politics than legal principle, may help repair the Court’s tarnished image.

A Good Year for Liberals Before a Conservative Court

Indeed, it is worth noting, as the term draws to a close, that this conservative Court issued a surprising number of liberal decisions this term. It struck down mandatory life sentences without parole for juveniles; invalidated a penalty imposed on broadcasters for “indecent” speech; struck down a law making it a crime to lie about one’s wartime honors; extended the right to “effective assistance of counsel” to plea bargaining; invalidated most of Arizona’s anti-immigrant SB 1070; ruled that installing a GPS to monitor an automobile’s public movements requires a warrant; retroactively applied a liberalized crack cocaine sentencing regime to persons who had committed their crimes before the reforms were introduced; and held that the Sixth Amendment right to a jury trial requires the state to prove to a jury beyond a reasonable doubt all facts that increase a criminal fine. All in all, not a bad year for liberals before a conservative Supreme Court. But stay tuned, because next year it is likely to take up affirmative action, the Voting Rights Act and gay marriage.

Read more of The Nation‘s coverage of the ruling on the Affordable Care Act:

George Zornick on how the ruling makes it easier for Republicans to deny Medicaid coverage to millions.

Ben Adler on the Republicans’ renewed attacks on Obamacare.

John Nichols on the ongoing push for Medicare-for-all.