With the election this month of an Argentine pope, Argentina was briefly put under an international spotlight. The news cycle has since moved on, but the political issues roiling the country remain, and they are narrated all over the country’s urban walls.

The word graffiti comes from the Italian graffiato, meaning “scratched.” In Argentina, graffiti puts politics in public places for public consideration, communicating present conflict as well as past grievances. With a bit of context, graffiti enables an informed viewer to bear witness to past and present political realities.

In the United States, a common form of graffiti is a “tag”—a painted inscription of the pseudonym of the graffiti artist onto a wall or any available surface. In Argentina, while tags exist, it is more common to see graffiti with a political message. The sheer quantity of political graffiti is shocking to any visitor to the country. It is literally everywhere: on public, private and government buildings; bridges; underpasses; and even across the front of people’s houses or on their windows.

Pausing to understand the meanings of these hasty scribbles opens a window into understanding Argentina’s political issues and the ways frustrated citizens, particularly younger ones, are grappling with them. The walls truly do speak.

These graffiti photos are from ten different cities in the northernmost regions of Argentina in the provinces of Jujuy and Salta. They were taken in December 2012.

In Argentina, the past is very present. There is a substantial amount of graffiti that reflects deep dissatisfaction with historical events and the ways in which they are still resonate.

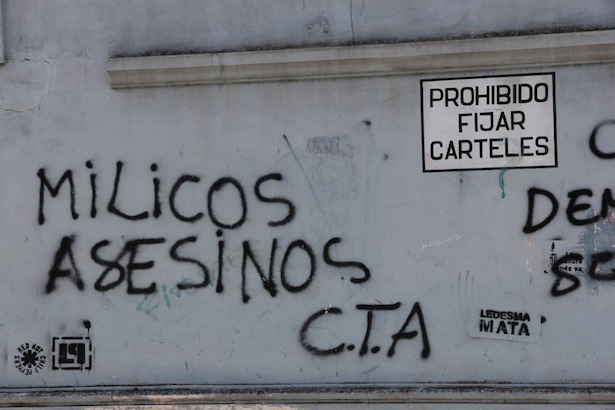

Argentine graffiti frequently includes the words milicos (military) and asesinos (murderers), accompanied by the name of a political figure.

This graffito makes the claim that many supposed perpetrators of crimes during Argentina’s dictatorship (1976–83) have gone unpunished to this day. During the dictatorship, a period that came to be known as the Dirty War, military officials and members of the Junta made over 30,000 members of Argentina’s political opposition ‘disappear’. The military accused the opposition of forming a terrorist movement in support of communism, and launched a campaign to eliminate its supporters. Many of these opposition members were later discovered to have been murdered by the regime in camps set up throughout the country by the Argentina’s military leadership, also known as the Junta. Because of the continued military threat during and after the country’s transition to democracy, hundreds of military leaders and supporters of the regime who committed such crimes were never brought to trial.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

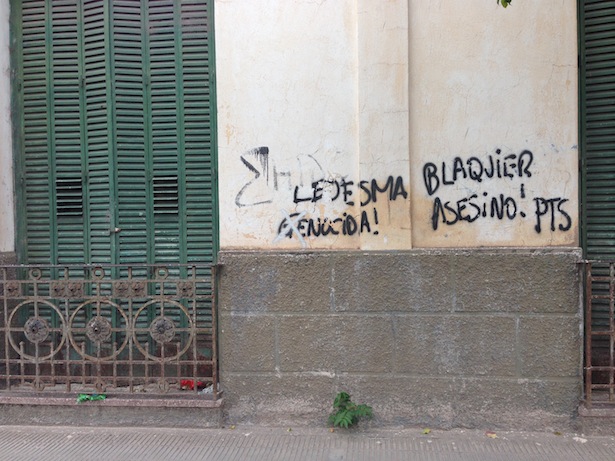

The image below has the name Blaquier and the word asesino. Blaquier is the owner of Argentina’s biggest sugar processing industry, Ledesma.

"Ledesma genocida! Blaquier asesino!" / "Ledesma Genocide! Blaquier Murderer."

He is now 85, and the graffiti on the walls accuses him of helping the military detain student activists in one of his factories in Jujuy province. The factory was transformed into a makeshift concentration camp where the student activists were tortured, beaten and interrogated during the dictatorship. In 2005, military trials were reopened after two of Argentina’s impunity laws were overturned, and in November 2012, Blaquier was first charged for his role in the crimes.

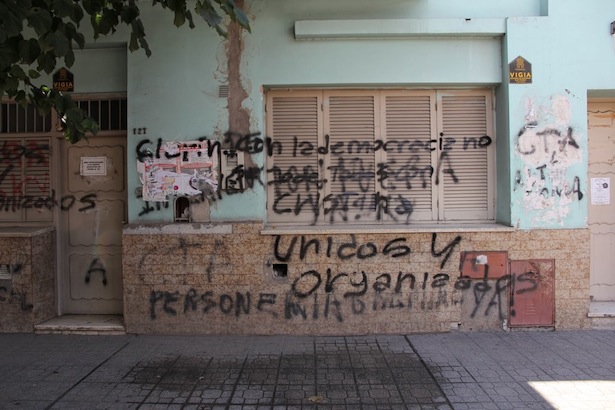

Cristina: "Con la democracia no se jode. Dejen de robar." / "Cristina: You don't fuck with democracy. Stop stealing."

Much of the graffiti I saw and photographed expressed discontent over current national politics. This graffiti translates to: “Cristina, don’t fuck with democracy,” referring to Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, the current president of Argentina. Among several reasons for these accusations could be the country’s current inflation rate (estimated by economists to be 26 percent, while the government cites it as 11.1 percent); the state’s assumption of control of private pension funds valued at 30 billion; the government’s restrictions on currency exchange, making it difficult for citizens to travel outside of Argentina; restricted freedom of speech; and, most significantly, an accusation of widespread corruption.

"Clarín: con la democracia no se jode. Todos con Cristina. Unidos y organizados." / "Clarín: You don't fuck with democracy. Everyone united and organized behind Cristina."

This particular graffito announces the dates of anti-government strikes: 13S, 8N, 6D, representing 13 September 8 November and 6 December of 2012. On these dates, thousands of people throughout the country marched against Kirchner and her government. This photo was taken in an affluent neighborhood in San Salvador de Jujuy, the capital of Jujuy province.

You can also see a mouth with an “x” across it. This image represents the current national conflict between Kirchner and the Argentine media giant, Grupo Clarín. In order to suppress content, much of which is critical of the government, Kirchner’s regime has cut off Clarin’s newspaper distribution and print supplies. Without substantial proof, the government has also accused Clarin of supporting the military dictatorship during the Dirty War.

The grafiteros behind this graffiti believe that Kirchner is attempting to eliminate Clarin in order to limit public access to information and to block freedom of speech. Eliminating Clarin would mean that the government would distribute the majority of the news via its publicly sponsored news corporations throughout the country.

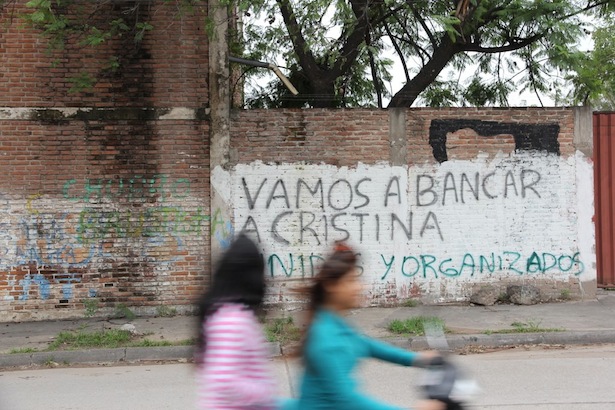

Those in support of Kirchner responded to the previous graffiti with their own pintadas. On walls throughout Argentina, much of the graffiti had the same expression in support of Cristina’s regime: “Clarin: con la democracia no se jode. Todos con Cristina. Unidos y organizados.” ”Clarin: you don’t fuck with democracy. Everyone United and Organized with Cristina.” These supporters of Cristina believe that Clarin publishes inaccurate information about the government and that it did indeed assist the military dictatorship.

Much of Kirchner’s support comes from the lower economic classes; they are less affected by the country’s growing inflation because their “purchasing power is more protected by the government’s social programmes,” according to a pollster quoted by the BBC.

"Vamos a bancar a Cristina. Unidos y organizados." / "We will support Cristina. United and Organized."

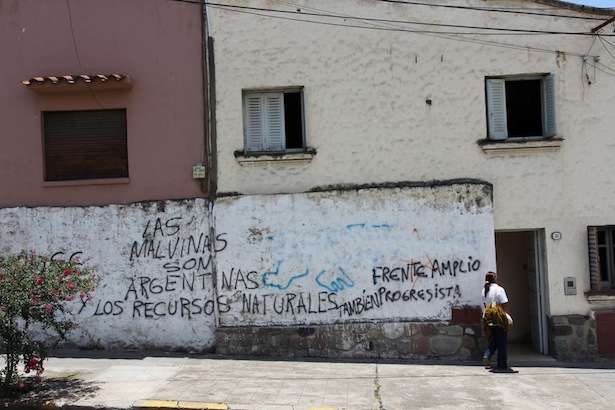

Argentina’s battle with the United Kingdom over the Malvinas islands is also the subject of much graffiti. The Malvinas are located approximately 310 miles from the Argentine coast but populated by British citizens.

"Las Malvinas son Argentinas y los recursos naturales también." / "The Malvinas are Argentine and so are the natural resources."

Both countries want jurisdiction over the islands because of their lucrative potential for oil exploration. In 1982, Great Britain and Argentina went to war over the islands. Argentina lost nearly 650 soldiers, with 320 of them dying after Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher sent a dispatch to sink the Argentine ARA Belgrano ship. This issue is also frequently cited by academic scholars as a defining moment that brought about the end of the country’s military dictatorship, as much of the public stopped supporting the military Junta after the loss. Over the past two years, President Kirchner has stirred up the issue again by making repeated claims to the islands in the media. Some argue that she is using the issue as a means to gain political support and popularity.

"Fuera la estación de Malvinas." / "Get the transmitter out of the Malvinas."

These images demand removal of an energy transformer in a residential neighborhood in Jujuy. The transmitter emits powerful rays that can threaten the health of the local population. The neighborhood is called the “Malvinas,” named after the contested islands. This graffiti was painted by a group that also has a website making similar complaints.

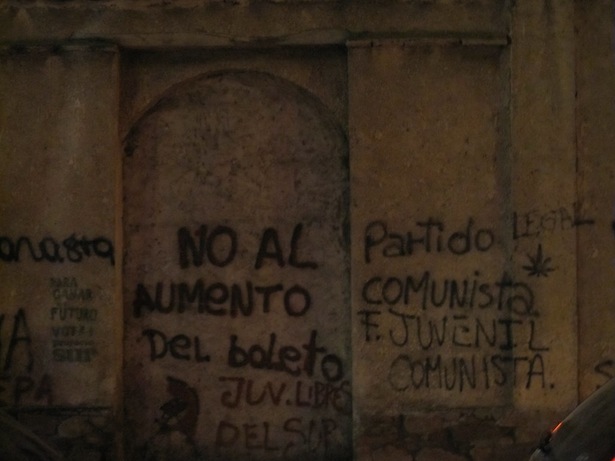

"No al aumento del boleto." / "Against an increase in bus ticket prices."

Finally, this graffiti reflects dissatisfaction with a local law that raised bus prices.

The world saw images of happy and hopeful Argentine citizens after the election of Jesuit Jorge Bergoglio as the first Latin American leader of the Vatican. Despite the festivities in the news, Argentina’s current political realities scrawled on its walls shows a population extremely frustrated. In his new position as leader of the Catholic Church, one can only hope that Pope Francisco will use his new position to also make efforts to help redress some of the searing political issues in his own native country.