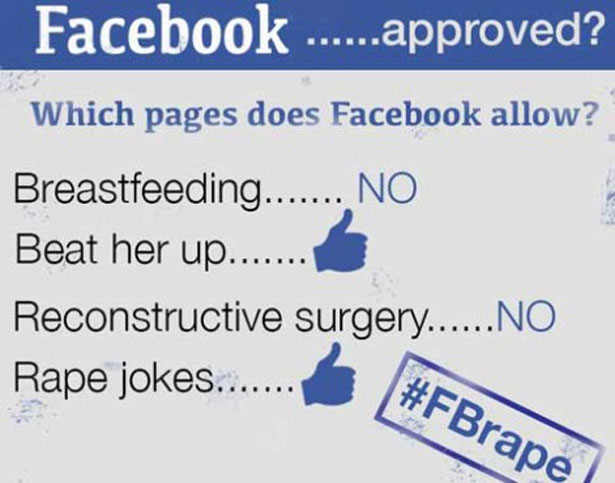

Photo courtesy womenactionmedia.org.

Feminists won big on Tuesday when an online campaign forced Facebook to revisit their policies on misogynist hate speech. In just a week, the protest—organized by Women, Action & the Media (WAM), Everyday Sexism and writer Soraya Chemaly—generated nearly 5,000 e-mails and 60,000 tweets directed at Facebook’s advertisers. After companies started to pull ads, Facebook responded with a lengthy statement committing to change their policies and admitting they hadn’t been doing their due diligence curtailing violent sexism: “In recent days, it has become clear that our systems to identify and remove hate speech have failed to work as effectively as we would like, particularly around issues of gender-based hate…. We need to do better—and we will.”

The success of the action is not just more proof that online activism is increasingly becoming feminism’s strong suit—from Facebook to Komen to transvaginal ultrasounds—but it also gives some hope that the culture is starting to shift around violence against women.

Jaclyn Friedman, executive director of WAM,* says the win left her “cautiously optimistic.” Friedman points to the outrage over the social media-documented rape in Steubenville, gang rapes in India and the suicides of several young rape victims as indications that Americans may have had enough of the consequences of rape culture. While she’s still unsure that the country is ready for widespread change, she believes “there’s a critical mass right now; it could be a tipping point moment.”

And with social media giant Facebook taking such a big step forward, Friedman says it could “move the bar for what we tolerate online.”

Like Friedman, I’m hopeful but wary—the fact that such a campaign needed to be launched at all is a depressing indicator of where American culture is on sexual assault and violence against women. That someone could think to post a picture of a dead woman who appears to be shot in the head with the tagline, “I like her for her brains,” or a woman lying at the bottom of the stairs with the line, “Next time, don’t get pregnant,” is enough to give any optimist pause. Even worse is that such hateful misogyny could be considered humor. And the fact that up until now Facebook didn’t classify this as “hate speech” means that the people behind these images and pages had their sexism validated and accepted.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

But this glaring, in-your-face misogyny may be the spark that pushes culture forward—there’s no arguing with these images, these court cases, these stories. Maybe it needed to get a lot worse—or more visible—for it to get better. For years, the most common anti-feminist talking point has been that American women don’t have it all that bad. That we should stop complaining and focus on women in other countries who are “really” oppressed.

But today, telling women that sexism doesn’t exist anymore is a really hard sell. Thanks to the Internet and the speed at which stories move—not to mention the vile sexism in most online spaces—any American woman who spends more than five minutes onlines hears about or experiences misogyny every day. And the absolute deluge of sexism—from “legitimate rape” and birth control controversies to rape jokes and high-profile domestic violence murders—makes it impossible for anti-feminists to call these stories anomalies in an otherwise equal society. What they really are is proof of systemic political inequity and cultural disdain for women.

So if we are at a serious tipping point—what should feminists do next? For issues of violence against women, I think the answer is clear. The action against Facebook is a great first step in focusing on the culture’s understanding of rape and domestic violence (something I’ve argued before). Now is also a perfect time for feminists to think critically about what kinds of stories capture their attention and energy. Why, for example, were so many feminists livid over Daniel Tosh’s rape “joke,” but forgiving of The Onion’s horrific piece describing Rihanna’s imagined violent death? It’s not real progress, or real feminism, if the mainstream movement only takes on causes that affect the most privileged.

For Friedman, her takeaway is that women need to know we can demand better. “Instead of thinking ‘that can’t be changed,’” she says, “let’s start thinking, ‘what can change that?’” The bad news is that there’s a lot that needs changing, but the good news is that it’s clear feminists—and maybe even all Americans—are up to the task.

*Full disclosure: Friedman and I co-edited a book together, Yes Means Yes.