Did you hear about the 1960s NFL player who also happened to be a Marxist? A player whose studies of Trotsky gave him more than he got from Lombardi? A player who unabashedly told reporters he was a member of an organization called the International Socialists? A player who quit the league in protest over the ways football mimicked and promoted the war in Vietnam? A player who, upon leaving the game, wrote a letter to a team owner that read, “Someday you are going to have to decide what is most important to you: the profit you make and the property you own or the establishment of a democratic egalitarian society. In such a society football as a professional sports activity will no longer take place and I hope that when the barricades are drawn you will be on the right side.”

It’s all true. His name was Rick Sortun, he was an offensive lineman for the St. Louis Cardinals, and he has passed away, at the age of 73, his family by his side and “Bob Dylan playing in the background.”

You won’t see any “NFL Is Family” ads celebrating Rick Sortun, because the NFL doesn’t look kindly upon its rebels, and he never thought of this league as a “family.” As he said to me several years ago over coffee in Seattle, “It’s big business. But a big business where all the workers go home in pain. No more and no less.”

Upon hearing of Rick’s passing, I contacted Rick’s friend and onetime teammate Dave Meggyesy, the ultimate NFL rebel who wrote the classic memoir Out of Their League. Dave said, “Rick was a man of great integrity and commitment for all worker’s right to unionize. A strong teammate and my on-the-road roommate with the Cardinals. Rick did not suffer fools, a true radical in the best sense of that word. He was a lifelong friend, and he will be missed.”

In many respects, Sortun was Meggyesy’s first “convert,” the initial teammate he won to a radical worldview from the conservative trenches of the 1960s NFL. Sortun was a Goldwater Republican, and the two teammates would argue ferociously. After his fourth year in the league, Sortun went home to Seattle during the off-season and joined the International Socialists, “I looked at his political transformation,” Meggyesy laughed, “and said,’Rick! What happened to you?’”

In Seattle, the massive lineman’s actions at protests were the stuff of legend: a giant of a man whom you wanted “blocking” for you amid building occupations and sit-ins. Sortun was attending the University of Washington in the off-season, earning his master’s in public administration. This connected him to the student movement and thes struggle to kick chemical weapons–maker Dow Chemical off the UDub campus. Ann Mackie, a friend of Rick’s said, “We did a lot of demos together. It was nice having him on our side when we took over buildings. He was one of the great guys.”

Another comrade of Rick’s from Seattle, Bill Roberts, said to me, “Rick was very principled in always standing up for the underdog and, in a quiet way, radiated forthrightness, and fellow-feeling. He was large in body, but larger in heart, who made a positive difference to all lucky enough to know him.”

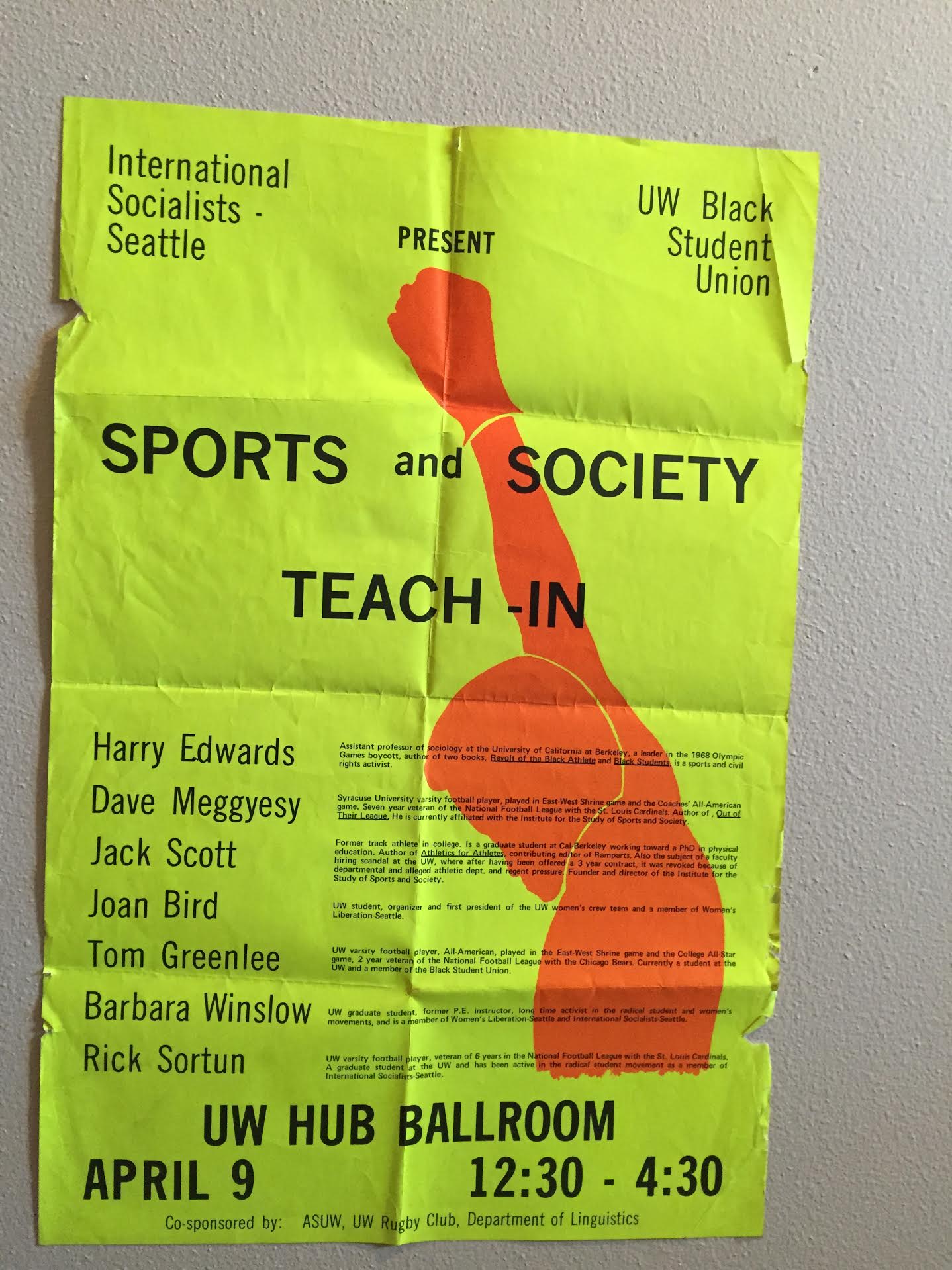

The pro-sports industry usually either defangs radical sports history (Muhammad Ali) or consigns it to the memory hole. Sortun is part of that hidden history of athletic rebels, someone who used this platform without fear to speak about his beliefs. Check this flyer from an event put on by the International Socialists. You have the legendary sports sociologist Dr. Harry Edwards; Jack Scott, a theorist of what was called “the athletic revolution” and someone who attempted to facilitate the escape of Patty Hearst; Meggyesy; pioneering crew captain Joan Bird; onetime physical education teacher and socialist Barbara Winslow; and Sortun. It’s a wild confluence of people, yet this is in no museum or Hall of Fame. It was found in Ann Mackie’s closet.

Yet what made Sortun so very special was the fact that he never stopped standing with labor. He became the longtime national president of the National Labor Relations Board Union, ironing out contracts and still walking the picket line. When I met him, he said being in the labor movement these last decades was “much tougher than the NFL,” but he didn’t waver. As his obituary in The Seattle Times put it, “Rick was always on the side of the worker.” He will be remembered for that more than for anything he did with a football. But if the NFL really is a “family,” it will mention the passing of Rick Sortun and not give short shrift on how he was truly “out of their league.”