Over the weekend, Kaniela Ing—the socialist candidate for Congress backed by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez—-lost his primary bid to represent Hawaii’s first district. Last week, Abdul El-Sayed lost in Michigan’s gubernatorial primary and Brent Welder failed in Kansas’s Third Congressional District primary. These losses have led many pundits to assert that a progressive agenda simply can’t win in most of the country. In Politico, Bill Scher writes, “The Berniecrat left desperately wants to convince naysaying political veterans (and annoying political pundits) that a democratic socialist platform holds the ticket to victory in heartland districts like this one,” but concludes that “It’s the future of the Bronx—and Detroit” only.

To be clear, it is better for the left when its candidates win rather than lose. But focusing exclusively on the horse race runs the risk of overlooking what really matters: Do voters support the policies of the Democratic left? A good way to assess the ascendancy of the left would be to examine public opinion on specific issues in specific districts. And our analysis of Civis Analytics polling as part of our New Progressive Agenda Project finds strong national support for many parts of the progressive agenda.

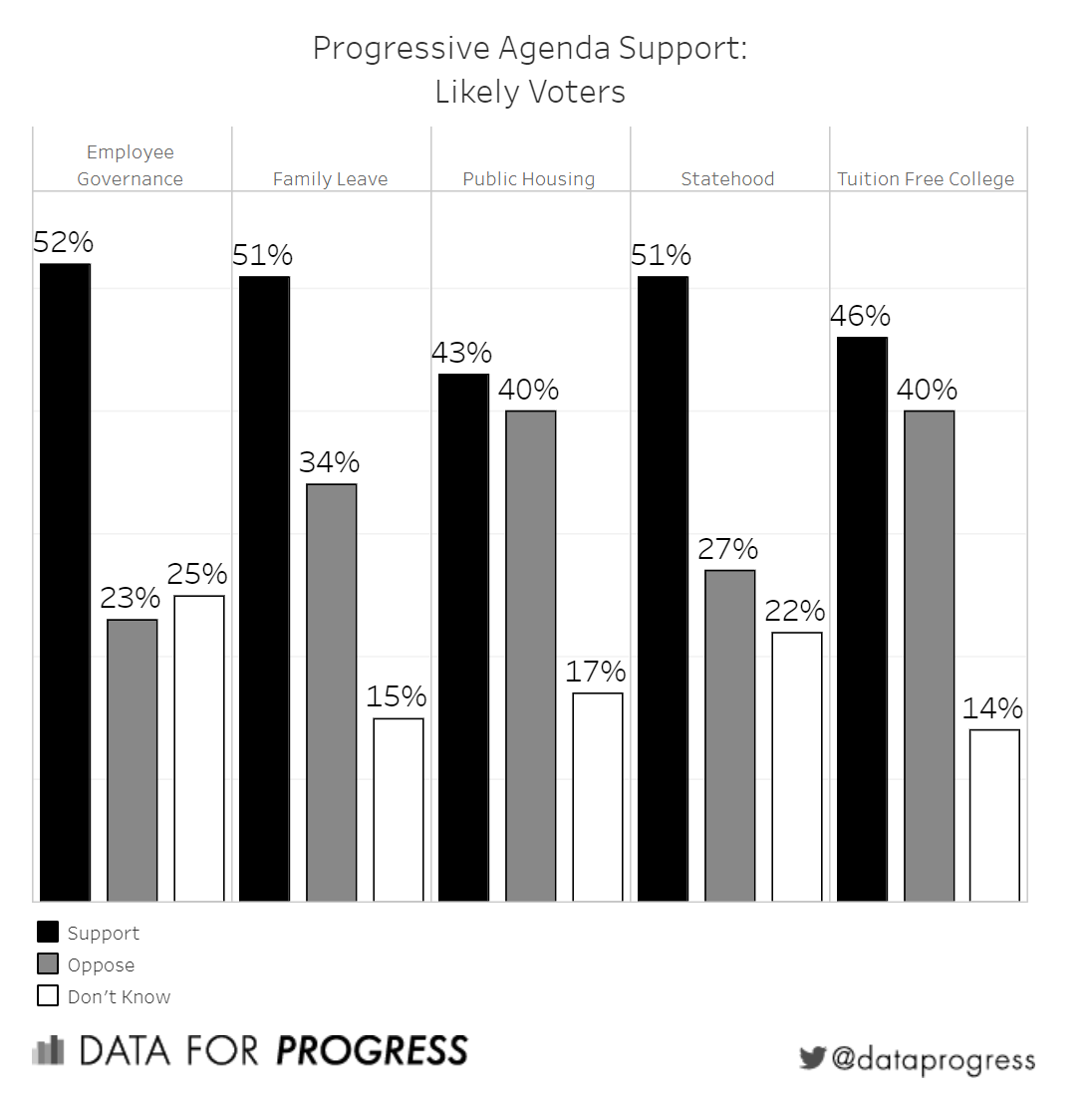

Nationally, all of these issues have net support from likely voters: free college (+6 net support), statehood for Puerto Rico and DC (+24) government-funded public housing (+3) and a policy that mandates worker representation on corporate boards (+29).

And what of a red district like Kansas’s third? Our analysis of Civis Analytics data suggests that paid leave, employee governance, free tuition, and DC Statehood all have net support among likely voters in the district.

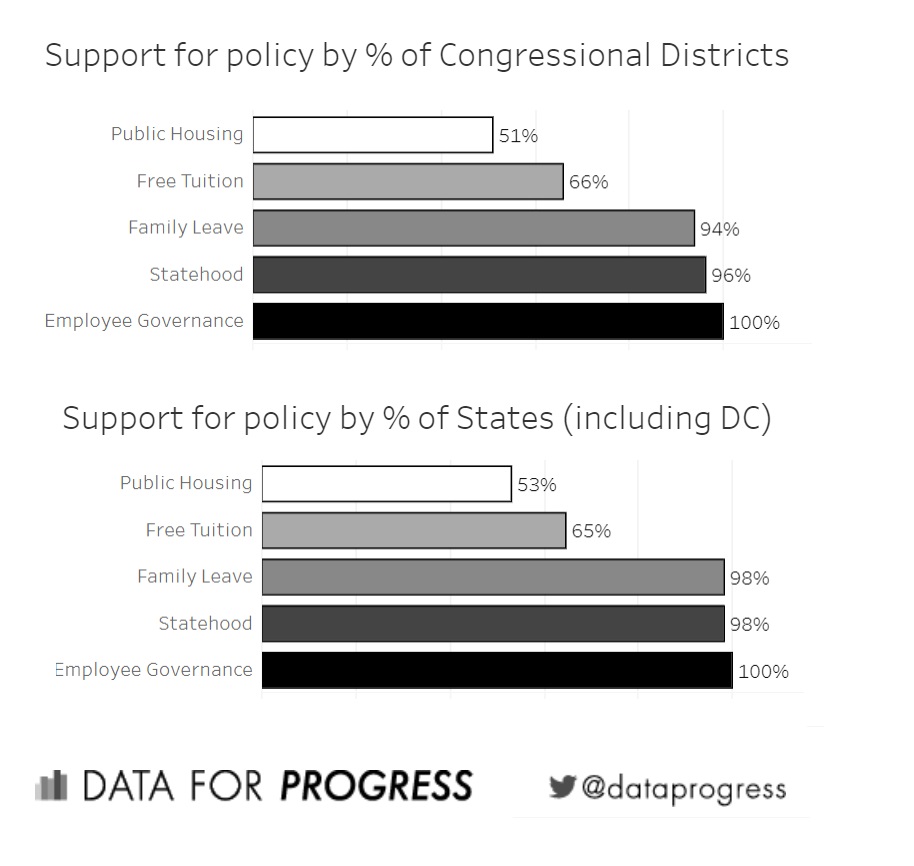

In some cases, progressive policies are even quite popular with Trump voters. The chart below shows the percentage of states and congressional districts where two-way support for the policies (excluding “don’t knows”) is greater than 50 percent (see more about our methodology here). You can see results for every district and state on our website, where our data was visualized by data scientist Jason Ganz.

We polled worker codetermination or employee governance, the idea that workers should have representation on company board of directors. The idea is radical in the United States context, but the practice is common in Europe. “Worker codetermination may well be the most popular policy that currently exists in American politics,” David Shor, head of data science at Civis Analytics’ political practice tell us, “This is the most popular policy we’ve tested for the New Progressive Agenda Project and one of the most popular policies we’ve ever seen, particularly relative to other labor issues.”

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Not only does it have majority support among Clinton voters, independent voters, and drop-off voters in every state, in many congressional districts it is popular with Trump voters. Though centrist pundits have suggested we need a “Boomer Corps” or deficit reduction as the policy platform to win back Obama-Trump voters, our data suggest the correct approach may be slightly different: giving workers more control over companies that employ them. As Tammy Baldwin tells us, “Wisconsin has a long and proud tradition of workers leading the way, but people all across the country are getting behind the idea of guaranteeing employees a seat at the table because it’s a clear, commonsense way to create shared prosperity for working families.”

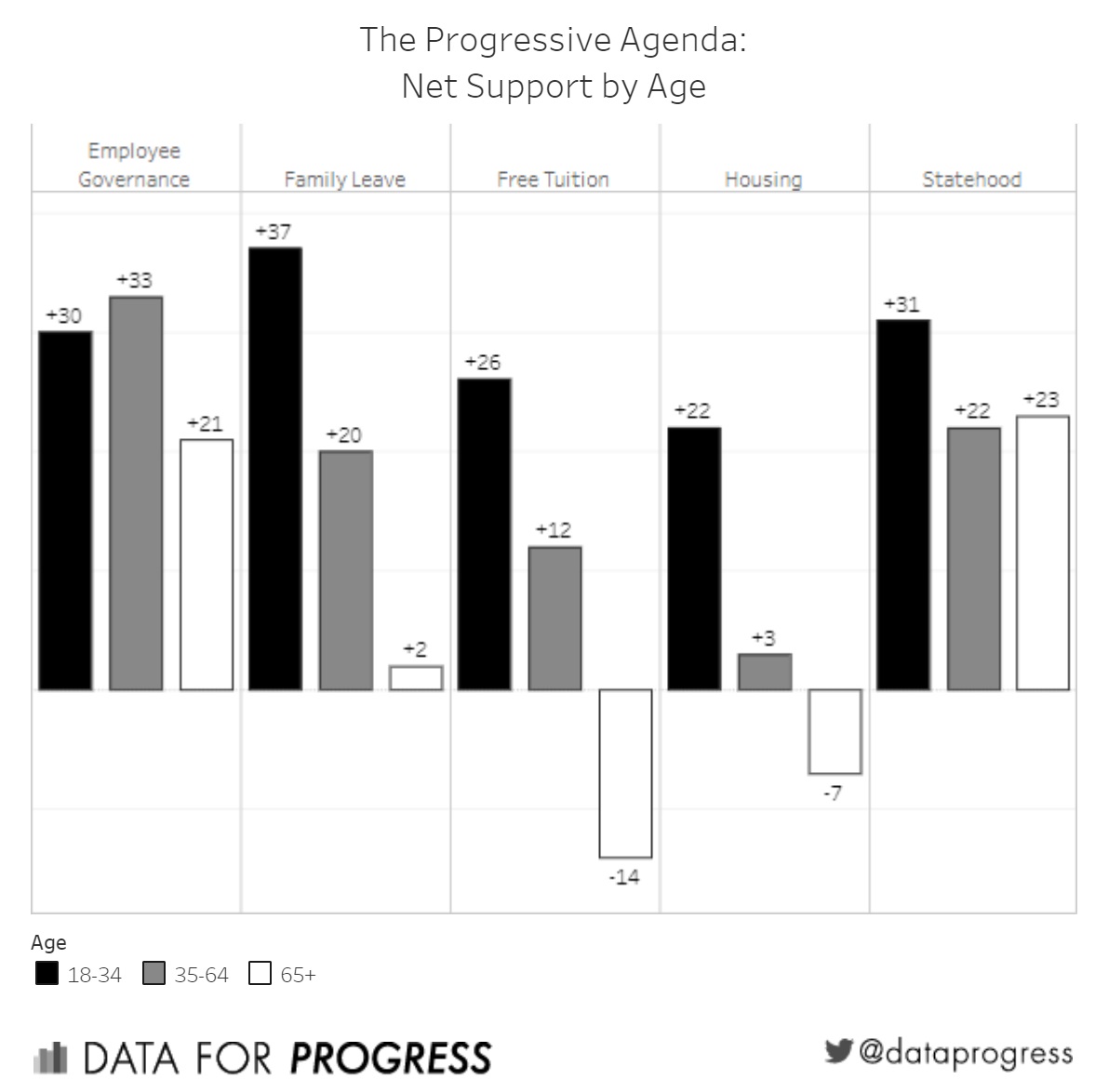

The progressive policies we polled are also popular across race and age groups. Young people and middle-age people support all of the policies, though the oldest likely voters are opposed to free tuition and public housing.

Black, Latino, and Asian likely voters overwhelmingly support all five progressive policies, and whites support all but public housing and tuition-free college. Family leave is popular nationally even without means testing—we didn’t set an arbitrary cutoff separating those who deserve paid family leave from those who don’t, and that didn’t seem to bother the public.

As the chart below shows, these policies are particularly popular with the young voters Democrats increasingly need to mobilize on election day.

This data is key to understanding what ideological pitches voters will be receptive to—not the outcomes of individual races. Much in the same way that Danny O’Connor’s one-point loss in the special election for Ohio’s 12th district does not signal that Democrats won’t be able to win tough races, El-Sayed and Welder’s specific successes or failures are the wrong standard to use when considering the viability of a progressive policy agenda.

This is particularly true in Michigan; El-Sayed had never run for elected office before and faced a candidate with a hefty statewide profile and the backing of unions and the local party—as well as a multimillionaire willing to spend almost unlimited sums to boost their name recognition. The question pundits should be asking themselves about his campaign isn’t why he lost; it’s why he got as far as he did in the first place.

For his part, Welder had trouble establishing authenticity in the district. Indeed, left House-watchers noted ahead of time that Welder’s biggest problem would be his weak ties to the district. There are many reasons why these candidates lost, but they are much simpler than Democratic primary voters’ deciding that they don’t actually think a public option for Internet access is a bad idea.

Given the popularity of left economics, why aren’t more Democrats running in that direction? Aside from a reluctance to challenge entrenched and monied interests, there is also a fundamental misunderstanding of what voters want. A growing political science literature suggests that policymakers tend to be to the right of their voters because they perceive voters to be more conservative than they actually are. In a recent study, political scientists Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, Leah Stokes and Matto Mildenberger found that only 14 percent of state legislators and legislative staff in 2017 reported that public opinion polls were “very important” in learning about their constituents’ opinions, compared to 71 percent who believed in-person meetings were the best gauge, or 44 percent who thought the same for phone calls, e-mails, letters, or faxes).

“Mounting research indicates that politicians and their top aides have only a murky conception of their constituents’ attitudes on a range of important policy issues,” Hertel-Fernandez said. “In our research, Congressional staffers were often off by twenty percentage points or more when considering their constituents’ opinions on repealing the Affordable Care Act, enacting tighter restrictions on carbon emissions, instituting background checks on gun sales, boosting the minimum wage, and increasing infrastructure spending.”

Campaigns often have limited resources to poll on policy issues that are important to them, and think tanks rarely provide them with accurate data relevant to their races. However, when they are provided with data, they move to where the public is. Political scientists Dan Butler and Dan Nickerson gave half of the New Mexico legislature district-level public opinion data on the governor’s spending proposals and found that the legislators with data voted more closely in line with public opinion than those that did not.

For years, progressives have been told that there policies would jeopardize the general election chances of Democrats. Our data suggest that in nearly every case that’s not true.

To be clear, progressives should be realistic about the challenges ahead. Simply adopting popular ideas is not enough to win elections, and a good policy platform is no use without an organized grassroots movement behind it. In addition, recent events in Washington, DC; New Jersey; and Seattle have shown that complete control of a government by Democrats is not enough to guarantee that popular progressive policies will actually be implemented. However, our data should make it clear that politicians who oppose these progressive policies aren’t doing so to their electoral advantage.