“Old wineskins must make room for new wine.” During the Rainbow Coalition days of the 1980s, Jesse Jackson used that biblical reference to press the Democratic Party to make structural and strategic changes in order to seize the opportunities presented by the country’s demographic revolution.

Today, this change is more imperative than ever, with an unprecedented number of Democratic gubernatorial nominees of color in the 2018 election cycle. These new candidates, propelled by large numbers of new and potential voters, create new opportunities for Democratic gains across the country. But to take advantage of these opportunities, Democrats will have to discard their old approaches.

Just two African Americans in US history have been elected governor: Doug Wilder in Virginia in 1989 and Deval Patrick in Massachusetts in 2006. This year alone, there are three black gubernatorial nominees: Stacey Abrams in Georgia, Ben Jealous in Maryland, and Andrew Gillum in Florida. In addition to the black candidates, there are three Latino gubernatorial nominees—David Garcia in Arizona, Michelle Lujan Grisham in New Mexico, and Lupe Valdez in Texas. And if that weren’t enough, the Democratic nominee in Idaho, Paulette Jordan, is bidding to become the first Native American governor in the country.

The very fact that these leaders are the nominees shows that they have already proven their popularity. What they need—and indeed, what most candidates of color need in a country where the average black or Latino family has just 10 percent of the net worth of the average white family—is money. That’s why this is a moment of truth for the donors and institutions who comprise the core of Democratic spending on gubernatorial races.

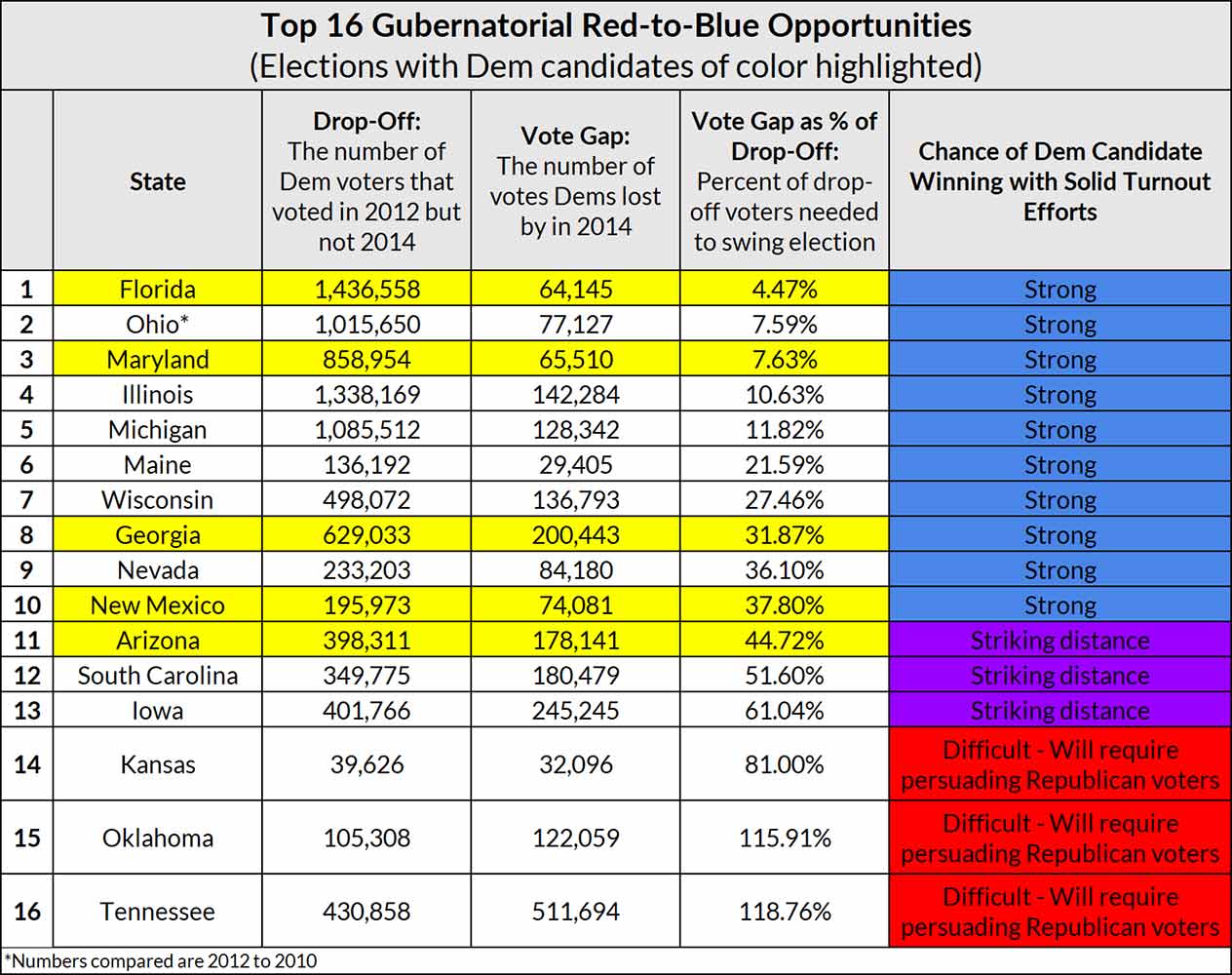

In each of the last two election cycles, the Democratic Governors Association, which is “dedicated to electing Democratic governors across the country,” has spent nearly $90 million on gubernatorial races. A data-driven analysis of the underlying composition of the electorates in all 50 states and the closeness of the last gubernatorial election shows that five of the top 12 battleground races have nominees of color.

Logic would dictate that Democratic investors should try to turn out as many Democratic voters as possible, especially in those races that are and have been the most winnable. People of color are consistently the most Democratic voters of all, giving nearly three-quarters of their votes to Democrats (in the case of Obama, the number was four-fifths).

Furthermore, academic research by Yale University professor Ebonya Washington and others has affirmed that candidates of color at the top of the ticket increase voter turnout among Americans of color.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Fortunately, some major players on the more progressive side of the party are taking note. Tom Steyer’s organization, NextGen, for example, stepped up in Florida, spent over $1 million in the primary backing Gillum, and turned Steyer’s organization’s infrastructure—with its 120-person staff and 1,000 volunteers on 45 college campuses—into an electoral army supporting Gillum. NextGen is quintupling down and investing an additional $5 million into the Florida election, recognizing that a rising tide of voters coming out for Gillum will lift all Democratic boats, including that of endangered incumbent US Senator Bill Nelson.

Alarmingly, other major players like the DGA do not appear to have adapted to the new environment, and are instead clinging to outdated approaches that have overlooked and under-invested in the candidates of color who have represented some of the best opportunities for Democratic gains such as Jealous in Maryland, Garcia in Arizona, and Abrams in Georgia.

The dozen blue or purple states with Republican governors offer the greatest potential for Democratic gains this year, and simple arithmetic suggests that a $90 million spending plan would allocate roughly $7.5 million to each of those top 12 most competitive states. That $7.5 million figure should obviously be adjusted for various factors such as size of a state’s population, but it is a useful baseline to assess the efficacy and intelligence of the political investments. But the DGA is falling far short of that benchmark.

Even where DGA is spending the most to support the nominees of color, it has still only allocated less than $4 million in each state (reports are that it has spent roughly $3 million in Florida and $1.3 million in Georgia). Campaign filings as of September 30 show just $765,000 from DGA going to support Abrams in Georgia. In Maryland, one of the most Democratic states in the country, DGA has invested nothing.

The old approach to making political-investment decisions relies primarily on polls, but polls are, by definition, rooted in the past, because the universe of those polled is determined by looking at who voted in 2014, not who is likely to vote this time around. That’s why pollsters missed the Gillum surge in Florida and the size of the Abrams margin in Georgia. And it’s why they’re underestimating the strength and potential of Ben Jealous’s running in Maryland, a state with twice as many Democrats as Republicans.

Compounding the problem is that, unlike NextGen, which is so transparent that it publicly posts the progress of its organizing efforts, the DGA operates in a shroud of secrecy that shields it from the best practices of transparency and accountability to stakeholders. As a result, there is little public rationale or explanation for why it is failing to properly invest in the states with the most promise for Democratic pickups. What we do know is that it has started advertising in Oklahoma and Kansas, states that are significantly whiter and less Democratic than the states with nominees of color.

The unprecedented diversity of this slate of candidates is not simply a statistical quirk. It is a natural response to the resurgent racism of this president and this moment. It should be no surprise, then, that leaders from the communities bearing the brunt of the attacks are standing up and fighting back. Most promising is that voters are responding in large numbers to these calls to take our country back.

The electoral math shows that these candidates can win, with proper investment. It is those who control the purse strings who must change how they do business.