Natural gas has no color. It has no odor. You can’t feel it. But with the right technology, it is possible to photograph it, and in 2014 NASA satellite imagery, a 2,500-square-mile methane cloud hovering over northwestern New Mexico is a searing hue of red.

As the earth heats up and sheets of ice and permafrost melt, more methane that is now trapped in the earth will escape to form other giant methane clouds,speeding up the process of global warming by way of the greenhouse effect. For now, the cloud above New Mexico’s San Juan Basin and the Four Corners region is North America’s largest on record. It’s the “personal opinion” of various natural gas and oil company executives and their affiliates that this cloud is a naturally occurring product of outcrops of vast coal beds, exacerbated by local coal mining operations. NASA scientists disagree: They say it is a consequence of natural gas processing, largely caused by to the 1 million tons—or $275 million worth—of methane that the drilling and fracking industry in the Southwest loses annually to pipeline leaks.

NASA’s colorful satellite pictures were Santa Fe artist Michael Namingha’s introduction to the hot spot. In a recent series of abstract, photography-based works, he juxtaposes sharp-edged polygons in bright red, neon pink and other colors against black-and-white chromogenic prints of aerial landscapes from the Four Corners region. The compositions are base-mounted to shaped plexiglass, creating 2-D graphic works that trick the eye to appear 3-D.

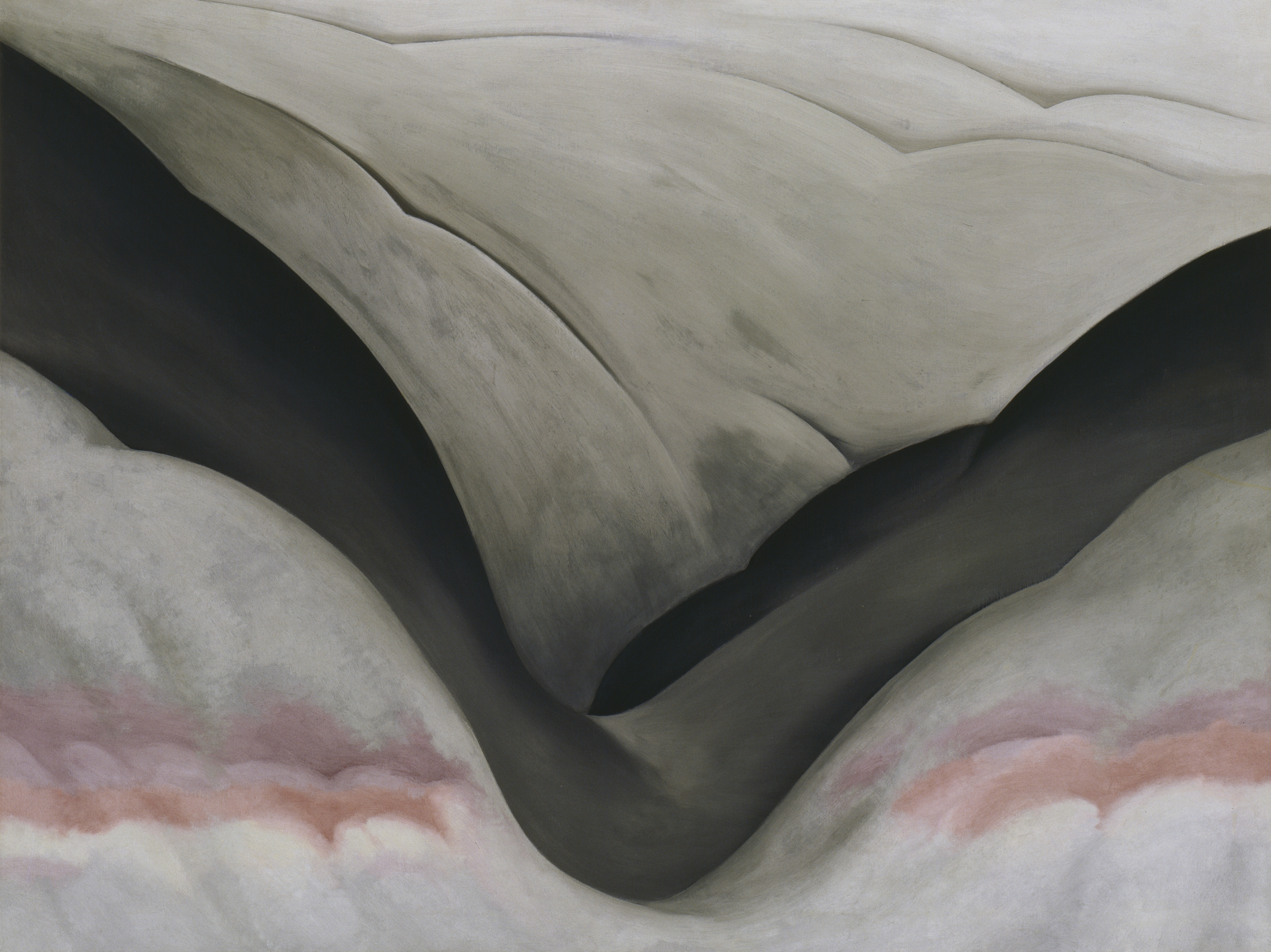

The formation Namingha chose to photograph is not just any otherworldly, volcanic desert, clawed through with white tiger stripes of ancient riverbeds: It’s the Navajo Nation’s Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness, which in the 1930s and ’40s captured the imagination of the mother of American modernism, painter Georgia O’Keeffe. She coined the badlands’ more widely known nickname, the Black Place, for its barren charcoal-colored mounds, and depicted the landscape abstractly in more than a dozen large canvases over the course of a decade. From her works, Namingha takes the name for his own.

With help from curators at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, Namingha visited the site and, having explored it before then only via Google Earth, decided to photograph it from above by drone. “The drone turned out to be a great tool,” he said in a phone interview from his home in Santa Fe, “because when we finally got there, I realized just how fragile that landscape is. There are parts where it almost crumbles like ash.”

On that trip, Namingha was taken aback by the overwhelming presence of the gas and oil industry. “Driving out there, we realized just how vast a network of drilling stations, water stations and refineries the industry has,” he said. “They have the whole infrastructure laid out.” Roaring Halliburton trucks, gas plants, fracking platforms, pipelines and chemical storage are all built up in a drilling site around Chaco Canyon, a national historic park sacred to the ancestral Puebloans, not quite 500 yards from the turnoff to the badlands where O’Keeffe used to paint.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

The first known oil well in the San Juan Basin was drilled on the Chaco Slope in 1911, decades before O’Keeffe painted her first Black Place canvas. Natural gas drilling there started in the 1920s. Pipelines were built to connect Albuquerque and Santa Fe in 1930, and by the early 1950s, they carried New Mexico’s oil and gas resources to California. Today more than 40,000 wells are in operation on tracts of federally leased land across the San Juan Basin’s 7,500 square miles. While 34,0000 acres of the Black Place and nearby Chaco are protected from drilling and fracking, an overground pipeline runs through the Black Place.

An estimated 140,000 New Mexicans live within half a mile of a drilling site. While the risks of methane waste and related pollution have not been extensively studied, they include health conditions such as respiratory ailments. According to the Environmental Defense Fund, these issues are hitting indigenous communities particularly hard.

O’Keeffe’s Black Place canvases, with their soft palettes and gentle eeriness, were hailed for capturing the essence of the natural landscape and the artist’s affection for it. In her work, the Black Place is mysterious and timeless. Namingha’s depictions are also somewhat abstracted, with his a spiritual follow-up to O’Keeffe’s impressions; aerial photography and blocks of color reference the land’s exploitation and imperilment. In 2018 this conversation played out in an exhibition at the O’Keeffe Museum of the series shown together, “The Black Place: Georgia O’Keeffe and Michael Namingha.”

“The thing about the O’Keeffe series especially,” Namingha said, “is that it raised awareness of what was—and is—happening in that region. A lot of people were just not aware. I got many people coming up to me saying, ‘I’m really glad you were able to convey that message through your work, because I had no idea that this was happening.’”

Namingha and his brother Arlo Namingha, a sculptor, follow six generations of Hopi artists.

As a child, their father, artist Dan Namingha, carved kachina dolls, figures that represent the spiritual intermediaries between Hopi people and the spirit world. As his 40-year career progressed, he would depict kachinas in abstract on canvas, along with architecture and landscapes evocative of his heritage. Departing from the visual patterns and imagery of traditional Hopi art, but retaining the cultural and spiritual themes, American Indian studies professor David Martínez writes that Dan Namingha’s painting and sculpture introduced Hopivotskwani—the Hopi way of doing things—into modern art.

Arlo Namingha took a similar path, working in more traditional Hopi forms and themes at the start of his career, then evolving into modern abstraction built on the same conceptual foundations.

Michael Namingha’s modernist works aren’t visually associated with the Hopi aesthetic, and he doesn’t think of his work as reliant on his Hopi-Tewa heritage. But in using abstract landscape-based works to cut to the heart of environmental and land use issues, inviting his viewers to discover and dig into the subject matter, Namingha brings elements of his father’s practice to his own. Cody Hartley, the director of the O’Keeffe Museum, who accompanied Namingha on his first trip to the Black Place, calls Namingha’s work Hopi modernism. “What I think he’s trying to do,” Hartley said, “is inviting us to look, to open up these questions, and to be a little provocative without being didactic.”

In Namingha’s “Black Place” series, the colors he uses to bisect black-and-white landscapes are inspired by the colors of fracking site markers, NASA’s methane cloud images, and other references to the current land use. Across his previous series, the blocks of color stand for land that is being sliced out, disappeared, or stolen from sacred places. His 2014 “Galisteo Basin” series focuses on an ancient Pueblo trade route later used by Spanish explorers and its Native owners’ decades-long battle against oil and gas exploitation. Vivid polygons splitting the images represent land that might one day be gone.

The writings and lectures of naturalist and educator Terry Tempest Williams inspired Namingha’s 2017 series about the removal of nature words, like “clover” and “raven,” from the Oxford Junior Dictionary to be replaced by words like “MP3 player” and “voicemail.” His response to drilling in the West has influenced her, in turn: In his “The Escalade Project,” a turquoise triangle slices through an aerial photograph of the Colorado River basin, referencing a controversial proposed Grand Canyon tourism infrastructure project that would build a tramway, hotel and restaurant complex into a cliffside at the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado rivers. As Williams writes in the preface to her 2016 book Erosion: Essays of Undoing, she was brought to tears when she first encountered his work at the Naminghas’ family gallery, Niman, in Santa Fe; it spoke to her heartbreak over the slicing up of the desert around her home in Castle Valley, Utah, by roads for natural gas extraction.

Curators have seized on Namingha’s background and frame of reference to place his works in dialogue with other indigenous artists whose work deals with themes of ownership, appropriation, exploitation, and recontextualization of Native American lands. A 2016 show, “You Are on Indian Land,” at the Museum of Northern Arizona included Namingha’s photographic series from the pilgrimage to Chimayó, a sacred site in north-central New Mexico. The text-photo works referred to the site’s appropriation by evangelical Christians with an obtrusive series of signs broadcasting guilt-inducing Christian messages. Other works in the show shared themes of colonialism, place names, and entitlement to and erasure of tribal lands from Native perspectives, including works by Cannupa Hanska, whose site-specific performance Settlement will take place at an upcoming Mayflower festival in Plymouth, England, as well as Nicholas Galanin, who told Mic that his installations and photography “come from a place that has known ‘America’ before ‘America’ decided to call this land ‘America.’”

While Hanska and Galanin deal with these themes head-on, Namingha’s work is in contrast nonconfrontational, even quiet, as if hovering far above the ground, where the sounds of oil trucks and heavy equipment fade away.

Namingha recently returned to Santa Fe from New York City, where he was part of an artist incubator program at the New Museum. Prior, he lived in New York, where he attended the Parsons School of Design to study fashion and branding. “Growing up, I learned to respect the land. All living things, plant life, water…the earth as a whole is our responsibility to respect and take care of,” he said. “I think moving away to New York City where there’s so much artificial landscape really made me realize just what it is that I have with the environment around Santa Fe. You can drive not far outside the city and it’s completely open land with big sky.”

Santa Fe is so visually and energetically integrated into the Southwestern desert, one can be on the city’s outer highway belt and barely detect its presence. There are few to none of the typical American urban architecture signals of a downtown—no glistening glass and metal buildings reaching dozens of stories into the sky. In curvature and in color, the city evokes the desert. After driving 20 minutes or less from its center, one can reach sage-scrub-covered expanses, forested mountains, and a million and a half acres of preserved national forest and wilderness.

“When I was in New York, I really missed the nature and openness, and in a way, it really started to inform my own artistic practice, in relation to what’s currently happening across the globe,” Namingha said.

Now the artist is focused on a new series that he started at the New Museum: “Altered Landscapes.” Just before returning to Santa Fe from the residency, he witnessed a sunset so searingly bright, he said, he found it disconcerting. “The colors were so intense, it was surreal. I was told it was because of all these wildfires occurring in Canada, that the smoke coming down was really changing the colors we were seeing,” he said. “It’s beautiful to look at, but it’s not supposed to be there.”

The scene reminded him of a line from Tom Ford’s 2009 film A Single Man: “Sometimes awful things have their own kind of beauty.”

“It made me think about that line,” he said, “and it made me think about where to go with my own work after the Black Place.” In “Altered Landscapes,” he manipulates aerial images of imperiled landscapes, removing the natural sky and replacing it with color is that is both beautiful and unnatural.

But after another year of massive California wildfires, the striking thing about these unnatural skies, he said, is that “they’re not that far from the truth.”