Five years ago, I was in my living room in New Jersey, finishing up a dissertation on chastity in 19th century Russian literature when I got a call from the CIA. As the recruiter went through the details about why he wanted me to work in clandestine affairs, I found myself impressed by his timing. He had known precisely when to call; at any other time in my life, nothing about this offer would have been attractive. I grew up being told the CIA was why we couldn’t have nice things (like democratically elected leaders in South America). But I was at a low point. I had no job prospects, was about to lose my health insurance once I finished my PhD, and was planning to move back in with my parents at the age of 28. I had become depressed and was behaving extremely out of character—I stole someone’s sushi from my university department’s refrigerator, attended an on-campus self-actualization workshop where an ex–McKinsey consultant asked us to meditate in a circle, and applied for a job working on a salmon fishing boat in Kamchatka. I felt lost and unwanted, and here was someone telling me that I could be James Bond.

A few weeks later, I divested myself of whatever fantasies I had about the CIA and the fast cars I might drive and multiple passports I might carry and told the recruiter that I couldn’t go through with it. “Good luck with your dissertation,” he said in response, which I tried not to read as a threat. I noticed soon after that when I told some of my colleagues the story, they seemed incredulous, even though we all knew other Russian literature PhDs who had been approached by “the agency.” The idea of a black woman working as a spy was bewildering to them. Spies are supposed to blend in, and whiteness—the racial default in the United States, at least—is presumed to carry with it a kind of invisibility. I also asked myself how I could work for the CIA, but for radically different reasons. For as long as it operated, the CIA made itself abundantly clear where it stood on questions of racial equality and black self-determination, trying to undermine the Black Panther Party and Martin Luther King’s Poor People’s Campaign and having a hand in Nelson Mandela’s arrest. How could someone black participate in that history, particularly on behalf of a government that treated us like second-class citizens?

These ideas all came back to me as I was reading American Spy, the debut novel by Lauren Wilkinson. American Spy follows Marie Mitchell, an African American woman who works for the FBI before being contracted by the CIA to help sabotage a socialist government in Burkina Faso in the 1980s. In a sweeping and action-packed story that stretches from Harlem to Martinique and Ouagadougou, the novel never strays too far from the two opposing forces in Marie’s life: her identity as a black American and her consequently vexed relationship with the history of the institutions she serves. The novel often flashes back to her childhood and teenage years, when Marie’s affections are similarly divided. Her father works as a New York City police officer, and her sister enlists in the military in the midst of the Vietnam War. Yet her mother, who hails from Martinique, reads Frantz Fanon and considers her husband and his FBI friends “snitches,” while Marie’s boyfriend, Robbie, is a Black Panther sympathizer who calls her sister a “sellout” (a word that will haunt Marie into adulthood). Later, her colleagues at the FBI question why she joined the bureau, suspicious of her true loyalties.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

In this way, American Spy is unlike traditional spy fictions, which tend to center on heterosexual white men whose patriotism, both in life and on the page, is never questioned. As Marie goes back and forth between identities and affiliations—an American agent in Burkina Faso, a black woman in the United States—American Spy suggests that by virtue of who she is, Marie is already skilled in what it means to be a double agent. There are shadows of W.E.B. Du Bois’s concept of double consciousness throughout the novel that suggest provocative parallels between spycraft and black life in America. As such, Wilkinson does not graft the matter of race onto the spy novel but rather asks us to think about how being a minority is, in a sense, an act of espionage, a precarious state marked by shifting identities, competing loyalties, and a constant threat of violence.

Marie joins the FBI’s New York City field office in 1985, the famous “Year of the Spy,” when a string of high-profile espionage rings was uncovered in the United States. She becomes especially intrigued by the story of Sharon Scranage, an African American stenographer for the CIA who was stationed in Ghana and coaxed into giving up state secrets to her boyfriend, a Ghanaian intelligence officer. Scranage’s case foreshadows the complex set of feelings that will come over Marie when she finds herself attracted to her eventual target, Thomas Sankara, a real-life Marxist revolutionary who became president of Burkina Faso and is known, even today, as “the Che Guevara of Africa.”

When we first see Marie on the job, she is meeting with one of her informants, a young mother named Aisha—“my favorite snitch,” as she calls her. Aisha’s uncle leads the Patrice Lumumba Coalition, an actual organization that was founded in New York City in the 1970s to support African liberation movements and to protest apartheid. The organization is under FBI surveillance, Marie explains, because of its ties to the Communist Party USA and because some of its members are former Black Panthers. The legacy of COINTELPRO, the FBI’s wide-ranging effort to subvert the activities of socialist, black nationalist, and civil rights organizations in the 1960s, is always in the background of American Spy. Marie recalls seeing her father’s friend, an FBI agent she refers to as “Mr. Ali,” on TV at Malcolm X’s funeral, speaking as the secretary for the Nation of Islam under an assumed name. “Mr. Ali,” Marie explains, had “been one of a small handful of black special agents hired during J. Edgar Hoover’s tenure at the bureau. They were brought on to participate in the Counterintelligence Program—COINTELPRO—and used almost exclusively to undermine civil rights activists.” Marie worries that by developing Aisha as an informer, she, too, is becoming part of that legacy. So she forges her boss’s signature to terminate Aisha’s contract—the first of many acts of insubordination Marie will commit as she begins to question her role and place in history.

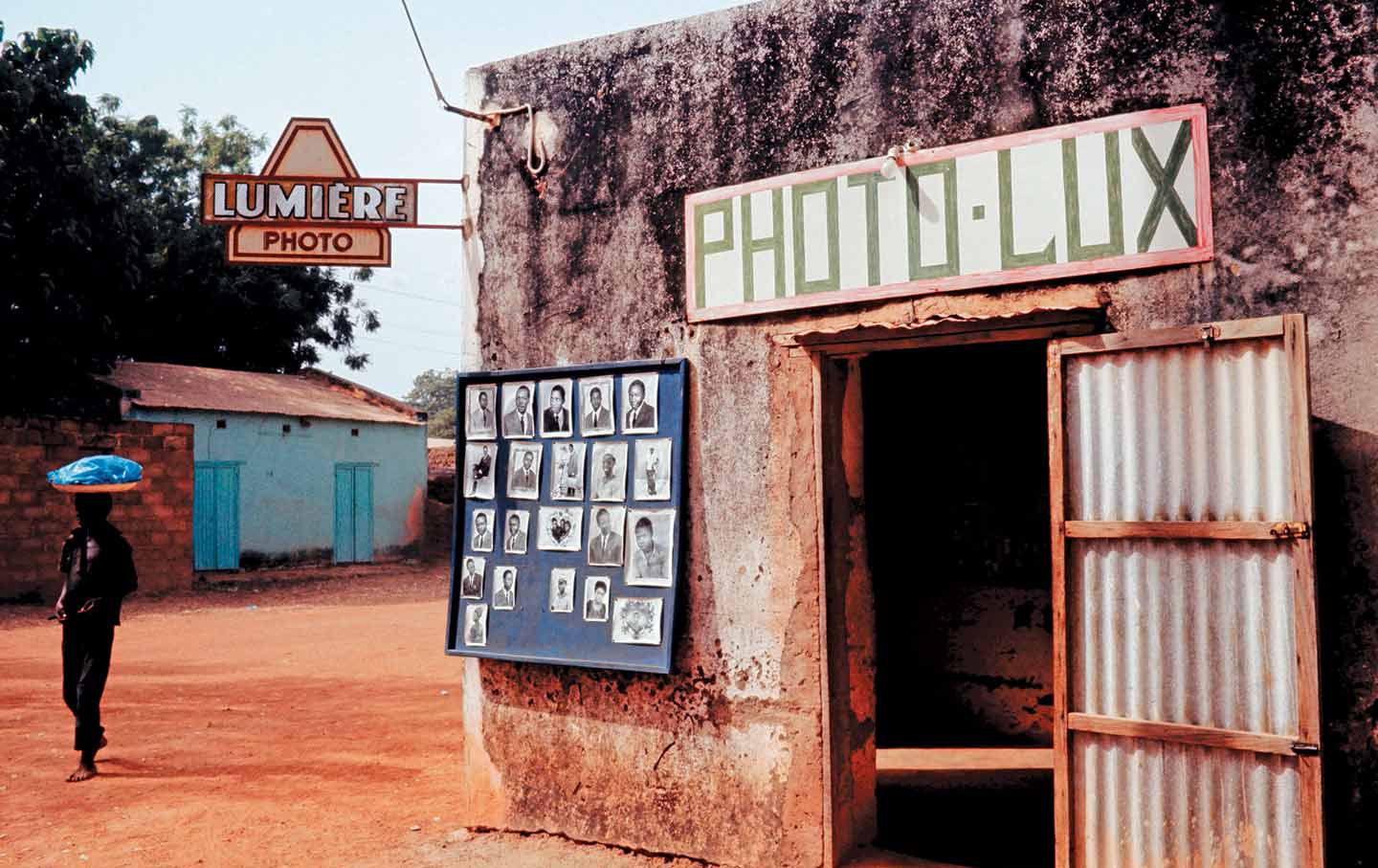

Marie is underutilized at the FBI. She feels there is a glass ceiling for her as a black woman and wants a higher-profile assignment, a chance to distinguish herself. The opportunity finally comes when Sankara, as Burkina Faso’s new president, comes to New York to give a speech at the United Nations. He is invited by the Patrice Lumumba Coalition to address a crowd in Harlem as well, and Sankara’s ties to the PLC give her an in. The CIA, which has installed an opposition party in Burkina Faso, wants Marie to pose as a UN aide and get close to Sankara to find out how much he knows about the agency’s involvement with the party. Eventually, the CIA sends her to Burkina Faso to work at an American NGO (one that gives refuge to women who have been accused of witchcraft). Her assignment is ostensibly to get even closer to Sankara and find out how much he knows about the US presence in the country, but Marie suspects a more nefarious plot is afoot.

American Spy is written in the form of letters from Marie to her two young sons. Years after the events in Burkina Faso, the three of them survive a home invasion and attempt on her life that leaves Marie’s would-be assassin dead. Fearing she might not have long to live, she writes the story of her life for her sons, trying to explain why someone would be after her and, perhaps even more important, to justify the choices she has made over her lifetime.

Wilkinson’s choice to frame the novel as a letter to two young black boys brings it into conversation with several other works that similarly confront issues of black life in the United States in epistolary form: Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me, James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, and Imani Perry’s Breathe: A Letter to My Sons.

The literary references throughout the novel are in many ways reflective of one of Wilkinson’s larger ambitions in American Spy: to redefine the spy fiction canon by thinking more expansively about what counts as an espionage novel. Though the novels of Ian Fleming and John le Carré certainly make their appearance, Wilkinson is writing as much in the tradition of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man and Nella Larsen’s Passing. Both novels explore the complexities of racial subjectivity in America by centering the question of what it means to carry multiple identities, to be at once black and American, an insider in one community and an outsider in another. For Marie, Passing is an important book: Her mother, Agathe, is light-skinned and was forced to pass for white by her aunt. Writing about Agathe to her sons, Marie observes, “She moved in and out of New York places where Negroes were interdits [forbidden], gathering her intelligence on the world that white people inhabited, always feeling she was about to be made.”

Marie often speculates as to whether navigating the racial divides of American society is what makes her such a good spy; when she takes on the assignment to infiltrate Sankara’s inner circle, she reflects, “It was my first undercover assignment, but I felt strangely confident; slipping into a false identity had proven to be easy for me. I’d had a lot of informal practice with performing different versions of myself to please other people.”

Performing different versions of herself is a skill we see Marie use over and over again in the novel, as she tries, as both a black American and a woman, to rise through the predominantly white and male ranks of the FBI—a feat that requires not so much code-switching as self-effacement. Inscrutability is Marie’s chosen defense mechanism against racism and sexism. Paradoxically, it has the effect of making her character seem at once underdeveloped and believable. She is impenetrable because she has to be. Like so many black women in white spaces, she finds herself forced to become skilled at making others feel at ease around her. “Spies have to be able to get close to people,” her sister tells her.

At the same time, Wilkinson’s story is also about the way that family can complicate identity and thus allegiance. We are accustomed to seeing our fictional spies quickly divested of family (e.g., the orphaned James Bond and Jason Bourne) and perhaps defined by that absence. However, Marie is defined by the overwhelming presence of one family member in particular: her father, the retired police officer. When Sankara and Marie walk around Harlem, he criticizes her father’s decision to become a cop (a fact that Marie doesn’t hide while undercover). “I think if you asked him he’d tell you he tried to do right by us while working within the system,” she explains. Sankara then tells her about his father, who served as a gendarme for the colonial government. When he wonders how black men could agree to enforce racist and unjust laws, Marie replies, “He was like my father: He wanted to ensure a better future for his children. That makes sense to me.” Marie’s pragmatism and her belief in the possibility of working within the system are what her relationship with Sankara will eventually test—ultimately leading to a dramatic twist in Burkina Faso, where Marie’s loyalties are complicated still further by desire.

Debates like the one Marie and Sankara have about the feasibility of working within a corrupt system to advance equality, particularly while black, are not new in African American letters. But they have gained a new currency in our culture in the wake of the Obama presidency. (Obama listed American Spy on his 2019 summer reading list.) The failure of his administration to push for bold agendas on issues like the racial wealth gap and mass incarceration spurred conversations about the limits of representation and neoliberal uses of identity. The logic of working from within systems to change them has been further tested in recent years, both in politics and culture. In the case of Senator Kamala Harris, the symbolic relevance of a black woman running for president was undermined by her record of tough-on-crime policies that disproportionately targeted poor minority communities. Films like Spike Lee’s BlacKKKlansman and Marvel’s Black Panther, which depict black protagonists cooperating with, if not working for, American intelligence agencies and law enforcement, brought this issue to the fore yet again. Critics like Boots Riley, the director of Sorry to Bother You, pushed back against Lee in particular, arguing that racial justice could not be won simply by diversifying organizations, like the police, that have historically perpetuated racial violence. “To the extent that people of color deal with actual physical attacks and terrorizing due to racism and racist doctrines,” Riley argued, “we deal with it mostly from the police on a day to day basis. And not just from White cops. From Black cops too.”

Wilkinson recognizes this danger as well but ultimately reserves her judgment, presenting the ethical choices faced by Marie as far murkier and more difficult to resolve, complicated by the multiplicity of allegiances that arise in a person’s lifetime. At its heart, American Spy is a refreshing take on identity that utilizes the tool kit of spy fiction to remind us of how wily a thing it is—for spies but for the rest of us, too. Marie is many things to many people, even when she is not undercover. As she shifts between Harlem, Martinique, and Burkina Faso, her identity shifts as well: “In the United States I thought of myself as black before I thought of myself as American. In Ouagadougou, routinely, those designations were reversed.” But unlike many of its predecessors, which score these shifts in identity primarily in a tragic key, American Spy tells the story of a fractured self as one that can be the basis for possibility and reinvention. If an agent is the sum total of her covers, then forging an identity in America is the ultimate spy thriller.