The 2020 Democratic presidential primary began as a thrilling, historic political experiment with a field that included no fewer than six women, four of them popular US senators. It wasn’t parity, but it was progress. A quarter of the 24 (or so) candidates running were women—roughly the same percentage as serve in Congress—and two were women of color.

While Hillary Clinton, the 2016 front-runner, became the Democratic nominee and ultimately won the popular vote, she was an anomaly: uniquely qualified and able to push almost all her challengers out of the race immediately but also uniquely wounded by her decades at the political front. 2020 would be different. In addition to the four senators—California’s Kamala Harris, Massachusetts’s Elizabeth Warren, Minnesota’s Amy Klobuchar, and New York’s Kirsten Gillibrand—we had New Age author Marianne Williamson and Hawaii’s Representative Tulsi Gabbard, an Iraq War veteran. For the first time, we’d learn what happens when a group of women run against one another for the highest office in the land.

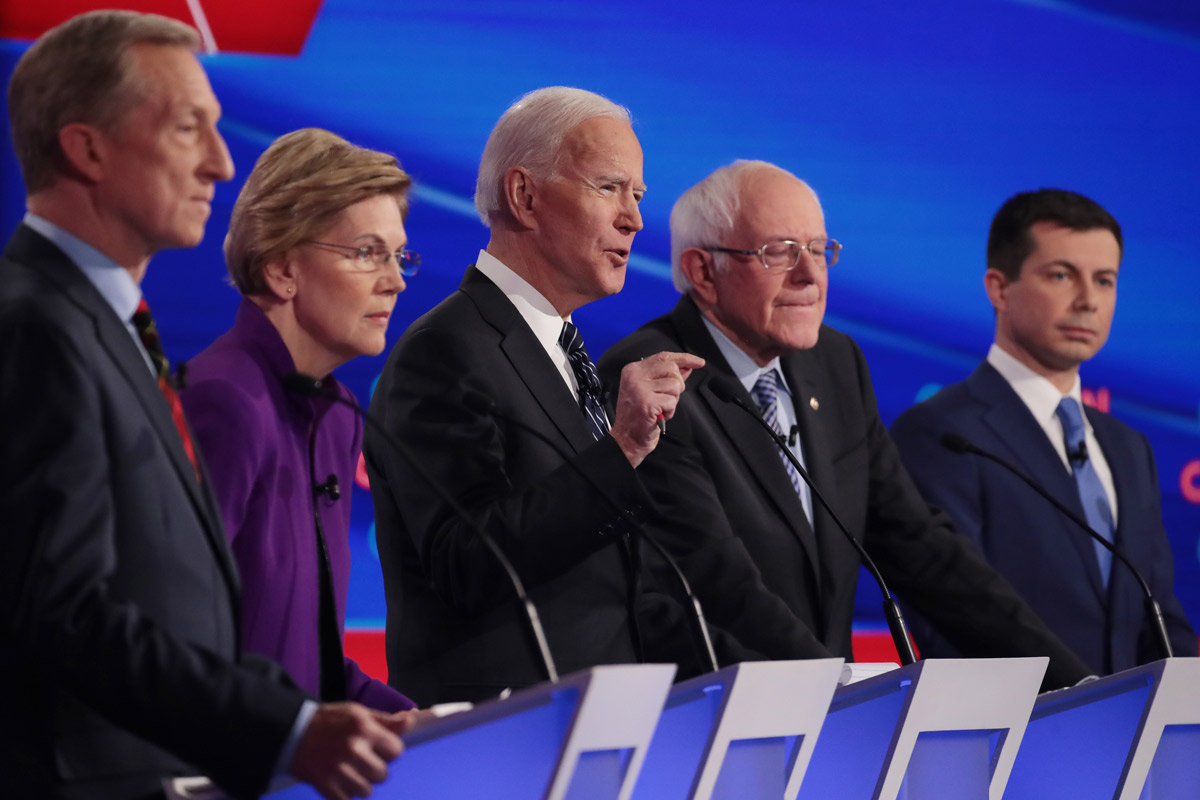

About a year later, just weeks before the Iowa caucuses, there were only six Democrats on the debate stage. All of them, unfortunately, were white, but one-third were women. That’s a measure of good news, at least, for women, right?

Maybe. But when progressive women talk among ourselves, we talk—fiercely but quietly—about the sexism that has made this road harder for the female candidates. We check ourselves because of the “bleak paradox” The New York Times’ Michelle Goldberg identified last year. As much as we want a female president, we believe that sexism played a big role in Clinton’s loss, and we see it hurting the female candidates this time around, too. But the more we talk about it, the more we remind Democrats, male and female, that nominating another woman is a risk.

Then came the report that at a precampaign dinner in December 2018, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders told Warren that he didn’t believe a woman could win the presidency. Initially, CNN cited anonymous sources; Sanders denied he said that, and he accused “staff who weren’t in the room” of “lying about what happened.” Then Warren confirmed their sources’ story, saying in a statement, “I thought a woman could win; he disagreed.” Within 24 hours, Sanders supporters, possibly amplified by trolls and bots, got #RefundWarren—a demand that she return donations from disappointed lefties—trending on Twitter.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

For many feminists, Sanders’s reported skepticism of Warren’s chances seemed yet more proof of the headwinds against the ambitions of all the female candidates, which helped push two promising female senators (Gillibrand and Harris) out of the race early As the backlash against Warren reminded us, the worst offense for a female candidate is to be—or to be called—a liar; the second worst is to be in danger of bringing down a popular male candidate.

No wonder former vice president Joe Biden said it so blithely in early January: Yes, Clinton faced “unfair” sexism (is there a fair kind?), but “that’s not going to happen with me.”

No, Joe, it won’t.

The record crop of female candidates seemed to be the big story of 2020, but at first they struggled to get any attention at all. Instead we were treated to glowing profiles of young male upstarts like former Texas representative Beto O’Rourke, whose campaign debuted in Vanity Fair, and South Bend’s ex-mayor Pete Buttigieg, an early media darling of Vogue. In March of last year, media critic Margaret Sullivan wrote in The Washington Post about the “potentially dangerous” ways media coverage of the “B-boys”—Beto, Biden, and Bernie—was eclipsing that of the four talented female senators in the race. (By the way, most women I’ve talked to agree that the most definitive proof of sexism in the 2020 race is the continued prominence of Buttigieg, a 38-year-old former small-city mayor, who unites us in the angry belief that no woman could get this far with a résumé so flimsy.)

The female candidates’ early struggle to gain traction took a toll. Gillibrand, who fought to attract donors and never got above the low single digits in the polls, tried to emphasize her leadership on women’s issues, particularly her fight against sexual assault in the military and her well-crafted proposal for paid family leave. But she dropped out in August, her candidacy mortally wounded by the perception that she (along with 33 other Senate Democrats, but who’s counting?) railroaded popular Minnesota Senator Al Franken into resigning after eight serious allegations of sexual misconduct surfaced against him.

Then came the shocking departure in early December of Harris, who had immediately become a top-tier candidate with an impressive campaign launch that drew at least 20,000 people in Oakland a year ago and who surged to the top tier after a standout debate performance last June. She ran on a platform of pragmatic solutions for struggling families, including a refundable monthly $500 tax credit and federal funds to boost teachers’ salaries, but she changed her campaign themes multiple times and eventually ran out of funds to support an ambitious early-state campaign build-out. (On January 10—not unexpectedly, given that she was polling around zero—Marianne Williamson dropped out as well.)

For her part, Warren, the most popular female candidate, has faced a kaleidoscope of sexist slurs and jabs since announcing her candidacy nearly a year ago. 2019 began with some pundits and activists mocking her drinking a beer in an Instagram livestream; 2020 began with some of the same folks mocking her dancing onstage in Brooklyn with former housing and urban development secretary Julián Castro the night after he endorsed her. His endorsement should have been the focus of Warren’s news coverage that night, but it wasn’t. Let’s hope “But she danced” doesn’t become shorthand for sexist media myopia in 2020 the way “But her e-mails” did in 2016.

Warren has had major highs and lows, some of her own making. In early 2019 she was unfairly written off as another version of Clinton, “elitist” and not particularly “likable,” and continued to be hurt by her decision to use (legally meaningless) DNA test results to “prove” her claim to an infinitesimal genetic Native American ancestry. But as she got deeper into her campaign, her warm, one-on-one retail politics strategy, with the endless selfie lines and the pinkie swears promising little girls they can grow up to become president, combined with her bold ideas—a wealth tax, Medicare for All, the Green New Deal, free public college—and her myriad detailed plans for them made her a front-runner by the fall. She racked up a series of endorsements from a diverse list of grassroots groups and activists, including the Working Families Party, Black Womxn For, and Medicare for All activist Ady Barkan, as well as positive headlines in mainstream and progressive news outlets. By early October, she was basically tied with Biden for the national lead, according to the RealClearPolitics polling average, and placing high in the early primary states too, as Sanders slipped a bit and Harris lost her post-June-debate bump. But Warren began to fall almost immediately.

These days, she seems to have arrested her decline, hitting a plateau in most recent polls and landing in second place, behind Sanders, in the all-important Des Moines Register/CNN/Mediacom Iowa poll released on January 10. With an outstanding field staff and a decent amount of cash on hand, Warren remains a formidable top-tier candidate. Klobuchar, who has positioned herself as the get-it-done moderate in a field of dreamers, also endures in the second tier of credible candidates.

But all of the female candidates have been undermined by double standards. When I talk to other women about sexism in the 2020 race, the complaints fall into two categories. First, female candidates get hurt by going on the attack, while men generally don’t. Second, women get dogged to provide more details about their policy plans—and then get criticized for those details.

“It matters that women be both credentialed and likable,” said Emily’s List vice president for communications Christina Reynolds. “Men don’t have to be likable.” The Post’s Sullivan concurred, saying, “One of the things that make women ‘unlikable’ is ambition, but ambition is essential to running for president. It’s a circle of hell that’s hard to overcome.”

Another circle of hell: To be seen as credentialed, women often have to produce more-detailed policy proposals than men, whose legitimacy are generally presumed. “We expect more of women in order to be credentialed,” Reynolds notes. “They can’t get away with broad policy strokes. They need policy details. But then the details are where they get in trouble.”

Let’s start with the problem of going on the attack. It’s expected of men, especially in this race, where it proves their macho bona fides against the bullying Trump. As I write, Sanders and Biden are hitting each other hard on their respective Iraq War histories, and the media covers it as business as usual. “Biden and Sanders Differ on Foreign Policy. They’re Happy to Tell You So,” announced a New York Times headline in early January, adding that both men seemed “energized” by the “renewed” debate. Yet women who go on the offensive, even with good cause, aren’t typically described as “energized” or “renewed.”

Gillibrand paid the price for her alleged aggression before she even declared her candidacy, in terms of her (widely exaggerated) role in prompting Franken’s resignation. The one breakout moment the senator had in a debate—when she unearthed a 1981 op-ed by Biden that opposed an expanded federal child care tax credit because it would contribute to “the deterioration of the family”—also cost her. Gillibrand interpreted the op-ed as an attack on working women; Biden took her raising it as a personal attack on him. He struck back personally, citing not only his track record on women’s issues but also her support for his stances. “I came up with the It’s On Us proposal to see to it that women were treated more decently on college campuses,” he replied. “You came to Syracuse University with me and said it was wonderful…. I don’t know what’s happened, except that you’re now running for president.”

Many pundits thought she had been unfair to Biden. In The Washington Post, Jonathan Capehart argued that Gillibrand “totally mischaracterized” Biden’s op-ed. Joe Pinsker in The Atlantic argued that “the truth is a little murkier” than Gillibrand’s attack. The op-ed was ideologically bizarre, but Biden indeed characterizes daycare as a way for parents to avoid the “individual responsibility” of raising their children. While reaching back almost 40 years for a hit on Biden may have made Gillibrand look a little desperate, for feminists, it felt like a fair-game example of the former vice president’s uneven evolution on matters related to questions of gender and family. After all, Biden supported the Hyde Amendment, which bars Medicaid funding for abortion, until about six months ago. But what I scored as a clear win for Gillibrand at least partly backfired. A few weeks later, she dropped out of the race.

Similarly, when Harris took on Biden, it buoyed her in the polls temporarily but cost her in the end. In June he got criticism for touting his early-career work with segregationist Senate colleagues like James Eastland and Herman Talmadge. In Biden’s most cringe-worthy statement on the subject, he kvelled that Eastland “never called me ‘boy.’ He always called me ‘son.’” The fact that “boy” is a slur traditionally reserved for black men went mostly unremarked by Biden. Reporters reminded us that Biden worked with segregationists on federal legislation to squelch court-ordered busing plans. New Jersey Senator Cory Booker, at that point also a presidential candidate, went after Biden for his work with segregationists, and Biden came in for criticism when he demanded that Booker apologize to him.

At the first Democratic debate, in late June 2019, Harris made her stand, saying, “It was hurtful to hear you talk about the reputations of two United States senators who built their reputations and career on the segregation of race in this country….you also worked with them to oppose busing.” She went on, “There was a little girl in California who was part of the second class to integrate her public schools, and she was bused to school every day.” Then the closer: “That little girl was me.”

Harris was quickly named the winner of the debate, and for a time, she climbed in the polls. Aimee Allison of She the People, which advocates for women of color in politics, was moved to tears by Harris’s story. “I felt like it showed she was uniquely prepared to lead the nation,” Allison said, “explaining how our rights and protections have been traded away by both parties.”

But the backlash began almost immediately. It turned out Harris’s campaign had a “That little girl was me” T-shirt ready to go, as well as a tweet to promote it during the debate. “That was a bridge too far for some people,” Sullivan recalled, incredulous. “It should not be a surprise that a candidate for president has a zinger prepared for a debate, as well as a tweet or two and maybe even some merchandise! But in some people’s minds, it made Harris too calculating.” Allison said, “It was as if she didn’t have a right to tell her story.” The Washington Times labeled Harris “the angry black presidential candidate.”

Biden hit Harris the way he’d hit Gillibrand—personally. “I was prepared for them to come after me, but I wasn’t prepared for the person coming at me the way she came at me,” Biden told CNN, reducing Harris to “the person.” Then he lowered the boom, invoking his late son Beau Biden, a former Delaware attorney general who died of brain cancer in 2015 and to whom Harris was close. “She knew Beau. She knows me.” (At least Joe Biden didn’t turn that into a T-shirt.) A full month after the debate, the Biden campaign and its surrogates were still crusading against Harris’s perfidy, summed up in the July 27 Washington Post’s headline “‘Beau’s flipping in his grave’: Biden supporters say Harris’s attacks betray her relationship with his son.” The piece crackled with recrimination, a fire that spread as countless Biden supporters told the same stories to countless political reporters. The Harris campaign made mistakes, but it arguably wasn’t punished for any of them as harshly as it was for her Biden critique.

Meanwhile, Warren, steadily rising in the polls, was able to avoid attacking her rivals. She came in for some criticism for her sassy response to a question about how she would answer a theoretical homophobic voter who believed marriage was “between one man and one woman.” She said she’d tell him that he should feel free to “marry one woman” and added jokingly, “assuming you can find one.” As New York’s Rebecca Traister noted, “Lots of people loved it. The clip went viral.” But some men weren’t so thrilled. The Washington Post, calling Warren’s quip “acerbic,” quoted Democratic strategist Hank Sheinkopf, who characterized it as “a battle cry for men to turn out against” her.

However, after Warren hit her early October polling high, she came under attack from some of the other candidates in the October 15 debate. Klobuchar and Buttigieg criticized her for failing to explain how she’d pay for Medicare for All, and Biden insisted she give him credit for whipping votes for the Consumer Financial Protect Bureau (which reporting suggests he didn’t do). The Washington Examiner called her an “unlikeable,” “petty,” “ivory-tower elitist.” O’Rourke branded her as “punitive” in how she talked about the wealthiest people in the country, even as he agreed that a wealth tax could be necessary. None of those are good looks for women.

By the December 19 debate, Warren was going on the attack, too. She took on the rising Buttigieg for the fundraiser he held in a “wine cave” and for his overall reliance on wealthy donors and closed-door donor events. She faced an immediate backlash, with reporters revealing that she held pricey fund-raisers with big donors when she ran for the Senate in 2012 and 2018. She has never denied participating in the corrupting farce of big-donor politics; why she gave it up for her 2020 run is a key component of her campaign pitch. But she was depicted as a hypocrite nonetheless.

Just a couple of weeks later, Politico reported that she was waving the white flag: “Warren ends wine cave offensive.” Damaged by her attacks on Buttigieg (who, it should be acknowledged, declined in the polls over the last month), she avoided critiquing him directly when asked about his fundraising haul and began returning her focus to policy. Politico reported that even some Warren supporters found her foray into negativity “disappointing.”

But if attacks can backfire, staying in your lane and playing nice with policy questions can hurt women, too. Harris stumbled more than once in explaining her stance on health care, first saying she would get rid of private insurance, then backtracking. By the time she announced her own plan, which would have maintained heavily regulated private insurance if people chose it, she’d lost the messaging war, even as many experts praised her combination of a high-standard private option in a mostly public system, implemented with a longer transition period than Sanders’s plan would provide. She was branded a flip-flopper on private insurance and dinged for having an inadequate grasp of her own health care policy, with Jacobin railing against her “phony Medicare for All plan.”

Warren may have been even more damaged by her Medicare for All rollout than Harris was, at least partly because policy and plans are supposed to be Warren’s thing. First she was attacked for not admitting that her plan would hike middle-class taxes. Then in November she got specific: She proposed that employers pay the government 98 percent of what they currently pay for private insurance, plus a financial transaction tax and other corporate tax hikes. Sanders described the employer contribution as a “head tax” that would hurt employers of lower-wage workers, and his supporters didn’t like that she proposed starting with a public option and builds in more time for the transition away from private insurance. So while she has been hit by the left for her go-slower approach as well as her funding plan, the media has mainly focused on how and when she would phase out private insurance. On CNN’s State of the Union in early January, host Jake Tapper asked Warren repeatedly whether private insurance would be banned by the end of her first term, though that would take a vote of Congress, and neither Warren nor Sanders can promise in the end that there will be at least 60 votes in the Senate for Medicare for All. Warren tried to tout the things she could do with executive orders and budget reconciliation rules, but she and Tapper wound up talking past each other, and she came off as evasive.

Sanders has benefited from consistency, as well as the fact that he said up front his plan would require a middle-class tax hike. But he has also benefited from leaving his plan vague and getting a pass on it. Could you imagine a world in which he is dogged at every interview with questions about how much taxes would go up and for whom exactly? He is not. As he said to The Washington Post’s Robert Costa, “I don’t give a number and I’ll tell you why: It’s such a huge number and it’s so complicated that if I gave a number you and 50 other people would go through it and say, ‘Oh….’”

While we’re on health care, Buttigieg’s “Medicare for All Who Want It” has a nice ring of the voluntary—for whoever wants it? Great!—but it’s far from voluntary. Buttigieg’s plan would not only institute a version of the Obama administration’s individual mandate, which was repealed under the Trump administration; if people fail to find their own insurance, it would enroll them into healthcare coverage and charge them at the end of the year. Public policy expert Matt Bruenig, a Sanders supporter, described it as a “supercharged” version of Obama’s “unpopular” mandate to The Washington Post in an article that ran on Christmas Eve and got no significant follow-up. The truth is that no one knows exactly how Buttigieg’s plan would work, and almost no one asks him.

Meanwhile, Biden’s public-option plan would put people into a government plan similar to Medicare, which isn’t specified. He backs an individual mandate, too. But he hasn’t yet spelled out how it would be enforced, and few reporters are grilling him. “The scant coverage that Biden’s plan received,” Libby Watson wrote in The New Republic, “failed to spark much of a broader conversation, despite the fact that there’s been a near constant demand placed on Medicare for All proponents to show how that plan would be financed. This is madness.” And the madness has continued right up to the eve of the first votes in Iowa and New Hampshire.

I had already been writing about the way sexism is playing out in the 2020 race when the Sanders-Warren dustup became public. It was painful, but at least it provided some clarity. Suddenly we were talking publicly about the way perceptions of electability hold women back. Not talking about it hadn’t worked to eliminate it.

To me, it seemed possible that both progressive senators could be telling their version of the truth: Sanders, gruff and blunt, might well think he was just speaking honestly when he told Warren—as he admitted he did—that the sexist Trump will weaponize gender against her. Warren, who has repeatedly been told her gender is a disadvantage in running for office, heard a bleak confirmation: Yet another man—one who is generally an ally—doesn’t believe a woman can win the presidency. But we’ll likely never know precisely what was said; they were the only two people in the room.

At first, appallingly, the backlash seemed to hit Warren, who was cast as a liar by Sanders’s supporters and even some of his campaign officials. First, #RefundWarren took over Twitter; after the debate, Sanders backers began using a snake emoji in tweets about her, which seemed to hark back to misogyny’s origin story, in which Eve listened to the serpent and got herself and poor Adam evicted from the Garden of Eden. Warren got blamed for leaking the story on the eve of the last pre-Iowa debate, when in fact, reporters have been chasing the story for a while, and The Intercept’s Ryan Grim tweeted that Warren told him the leak wasn’t intentional.

Warren was backed into a corner: She had to either confirm the story or call her colleagues liars. Sanders campaign manager Faiz Shakir predicted the latter when he told reporters, “We need to hear from her directly, but I know what she would say—that it is not true, that it is a lie.” Instead Warren said it was true, in a statement that also praised Sanders and urged that they put the issue behind them.

When it came up at the Des Moines debate, Warren was ready and turned the electability question on its head. “Look at the men on this stage. Collectively, they have lost 10 elections. The only people on this stage who have won every single election that they’ve been in are the women—Amy and me.” And the same had been true of the other two female senators who ran for president: Harris and Gillibrand had likewise won every race they’d entered, until 2020.

The crowd cheered; Warren had slain the electability monster. Or had she? On the one hand, it’s a little depressing that those four female senators had to have perfect electoral records in order to run for president when the men surely didn’t. On the other, Warren reminded us that despite the obstacles, women know how to win.

“Yes, women face sexism. Women also run and win,” said Christina Reynolds, pointing to the 23 Democratic women who flipped House of Representative seats in 2018, as well as those who have helped statehouses trend blue ever since 11 women nearly flipped the Virginia House of Delegates in 2017. Elizabeth Warren “is right. Democratic women outperformed men in #election2018,” tweeted Kelly Dittmar of the Center for American Women and Politics, whose research proved it.

For all this progress, we still haven’t shattered “the highest, hardest glass ceiling,” as Hillary Clinton famously described the presidency (even though she proved a woman could get almost 3 million more votes than a man—and still lose, thanks to the ultimate institution protecting white male privilege, the Electoral College). As I write, Warren and Klobuchar are still in the fight. For better or worse, we’re now past the point of trying to downplay the double standards that women face. And we’ll know more about them, because of the women who chose to compete in this inspiring, bewildering, and occasionally enraging Democratic primary.