EDITOR’S NOTE: The Nation believes that helping readers stay informed about the impact of the coronavirus crisis is a form of public service. For that reason, this article, and all of our coronavirus coverage, is now free. Please subscribe to support our writers and staff, and stay healthy.

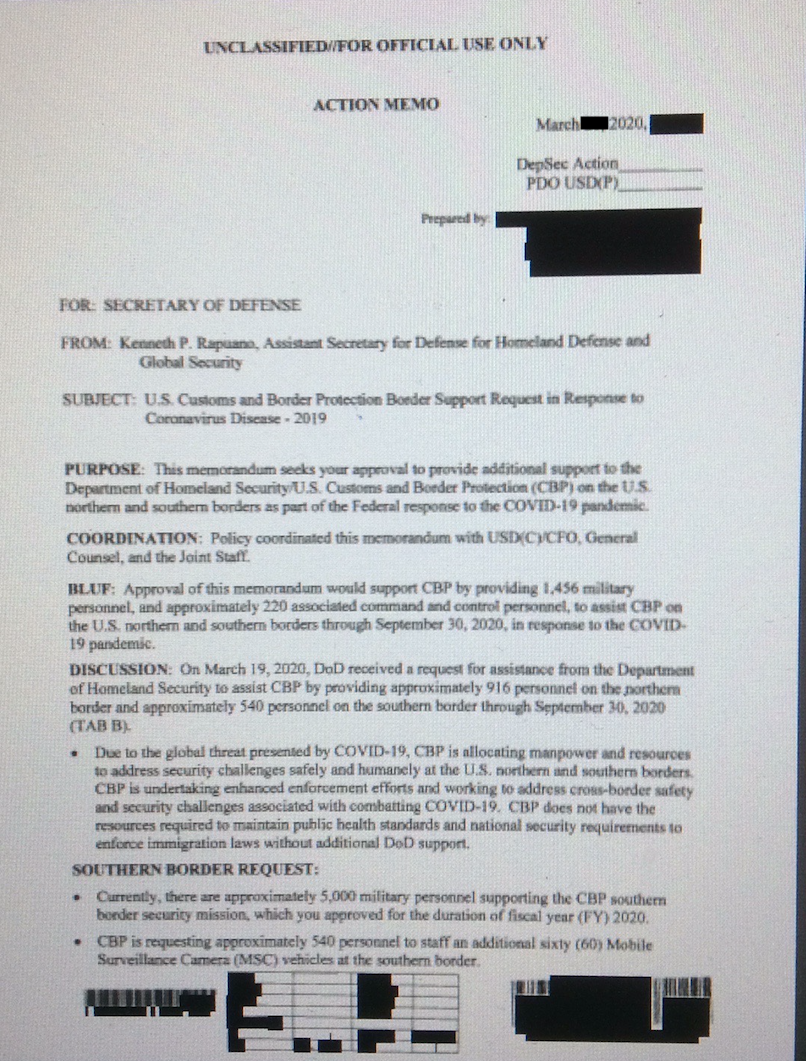

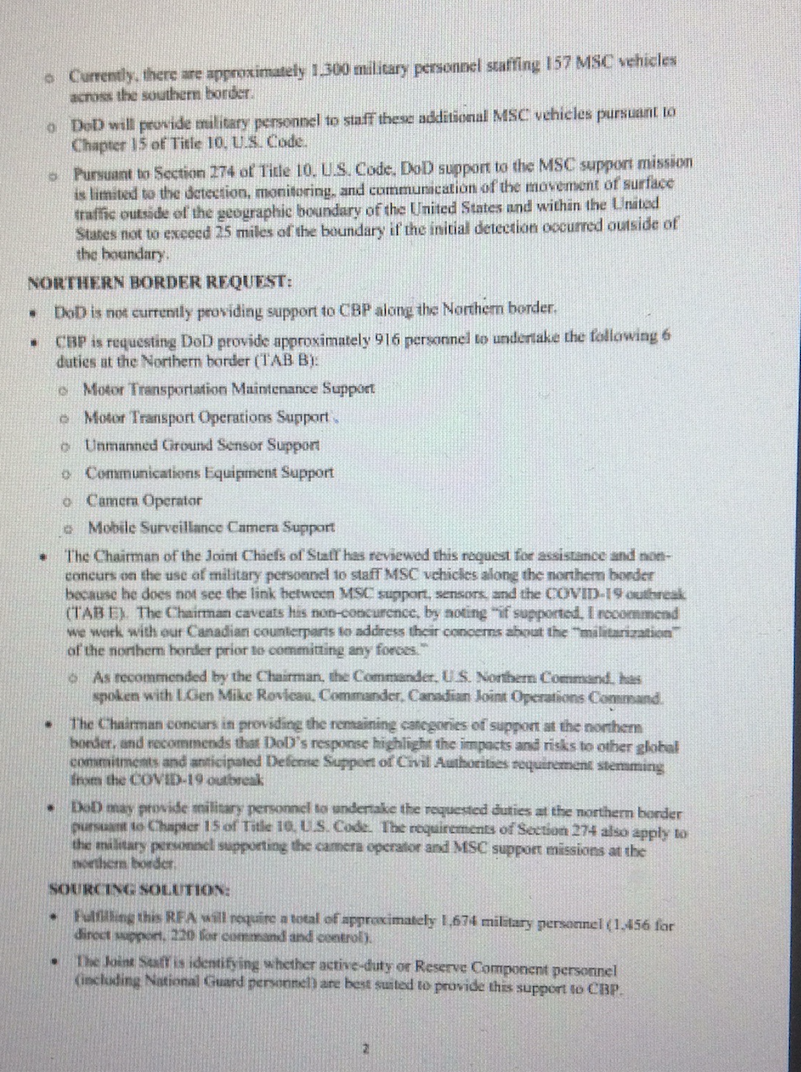

In late March, Customs and Border Protection (CBP) requested military support to surveil the US-Canada border with mobile cameras and underground sensors. The request was rebuffed by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who feared opposition from the Canadians, according to an internal Pentagon memo obtained exclusively by The Nation.

The memo reveals that CBP sought 916 military personnel to undertake duties at the Canadian border, including operating mobile surveillance cameras, unmanned ground sensors, and motor transportation. Overall, CBP’s request was estimated to cost $145.3 million.

In addition, it would provide 540 military personnel on the southern border—adding to the 5,000 military personnel including military police, marines, planners, and engineers.

The memo, marked for official use only, was sent from Kenneth P. Rapuano, assistant secretary for homeland defense and global security, to Secretary of Defense Mark Esper. It was provided to The Nation by a Pentagon official on the condition of anonymity to avoid professional reprisal.

Stephanie Carvin, a professor of International Relations at Carleton University in Ottawa, expressed outrage at the proposal, telling The Nation, “Americans remember 9/11, but Canadians remember 9/12 because that was the day our border shut down…. The United States is 80 percent of our trade—it’s our oxygen. If it’s cut off, we can’t breathe.…

“Militarization runs against almost everything institutional in Canadian foreign and domestic policy going back the last 20 years, and I don’t say that lightly.”

The memo ties Covid-19 to border enforcement, describing the request’s purpose as being to help CBP “as part of the Federal response to the Covid-19 pandemic.” But it later cites immigration enforcement as one of its goals. “CBP does not have the resources required to maintain public health standards and national security requirements to enforce immigration laws without additional DoD support,” it notes.

Despite CBP’s concerns, undocumented immigration to the United States remains relatively low, with the vast majority of it coming across the southern border. Furthermore, the incidence of Covid-19 is far higher in the United States than Canada or Mexico.

Political scientist Stephen Saideman, who serves as director of the Canadian Defence and Security Network as well as Paterson Chair in International Affairs at Carleton University, called the plan a “harebrained idea.”

“It seems like a strange use of resources at this moment in time,” Saideman said. “There is no threat of Canadians fleeing to the US given that national health care in Canada becomes a far greater magnet during a pandemic; Canada is not only a week or two behind the US in terms of the progress of the pandemic, but is also flattening the curve better; [and] there has not been much threat of illegal migration in this direction historically.”

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

The Nation previously reported on a memo from March in which the Department of Homeland Security requested military support up north, stating that “any unknown or unresolved illegal entries into the United States in between Ports of Entry (POE), have the potential to spread infectious disease.”

Carvin described the mood in Canada when the plan was first reported as “first shock and then laughter.”

President Trump has repeatedly accused foreigners of spreading diseases, accusing Mexican migrants of bringing “tremendous infectious disease…pouring across the border.” He has also demanded that Covid-19 be called a “Chinese” virus. But he has not publicly targeted Canadians—yet.

The US-Canadian border, often described as the oldest demilitarized border in world history, has historically been free of a military presence from either nation; but that could change under the Trump administration, which has already moved to restrict travel between the United States and Canada.

The plan does not appear to have been low-level speculation, judging from the seniority of staff involved. The memo notes that the commander of US Northern Command spoke about it with the commander of the Canadian Joint Operations Command.

While the chairman of the Joint Chiefs rejected the plan, he also appears to leave open the possibility, provided the Canadians approved.

“The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff has reviewed this request for assistance and non-concurs on the use of military personnel to staff MSC [Mobile Surveillance Camera] vehicles along the northern border because he does not see the link between MSC support, sensors, and the COVID-19 outbreak,” the memo states. “The Chairman caveats his non-concurrence, by noting ‘if supported, I recommend we work with our Canadian counterparts to address their concerns about the “militarization” of the northern border prior to committing any forces.’”

Maj. Mark Lazane, a spokesperson for the Pentagon’s US Northern Command, told The Nation, “DoD [Department of Defense] has a long history of supporting Customs and Border Protection in securing the U.S. borders; however, we do not have an approved mission assignment to support CBP along the northern border. For information regarding potential future support, please contact CBP or the Department of Homeland Security.”

Neither Customs and Border Protection nor the Department of Homeland Security responded to a request for comment.

Correction: A previous version of this article misattributed two quotations from Stephanie Carvin to Chrystia Freeland, Canada’s Deputy Prime Minister, who declined to comment. The story has been corrected.