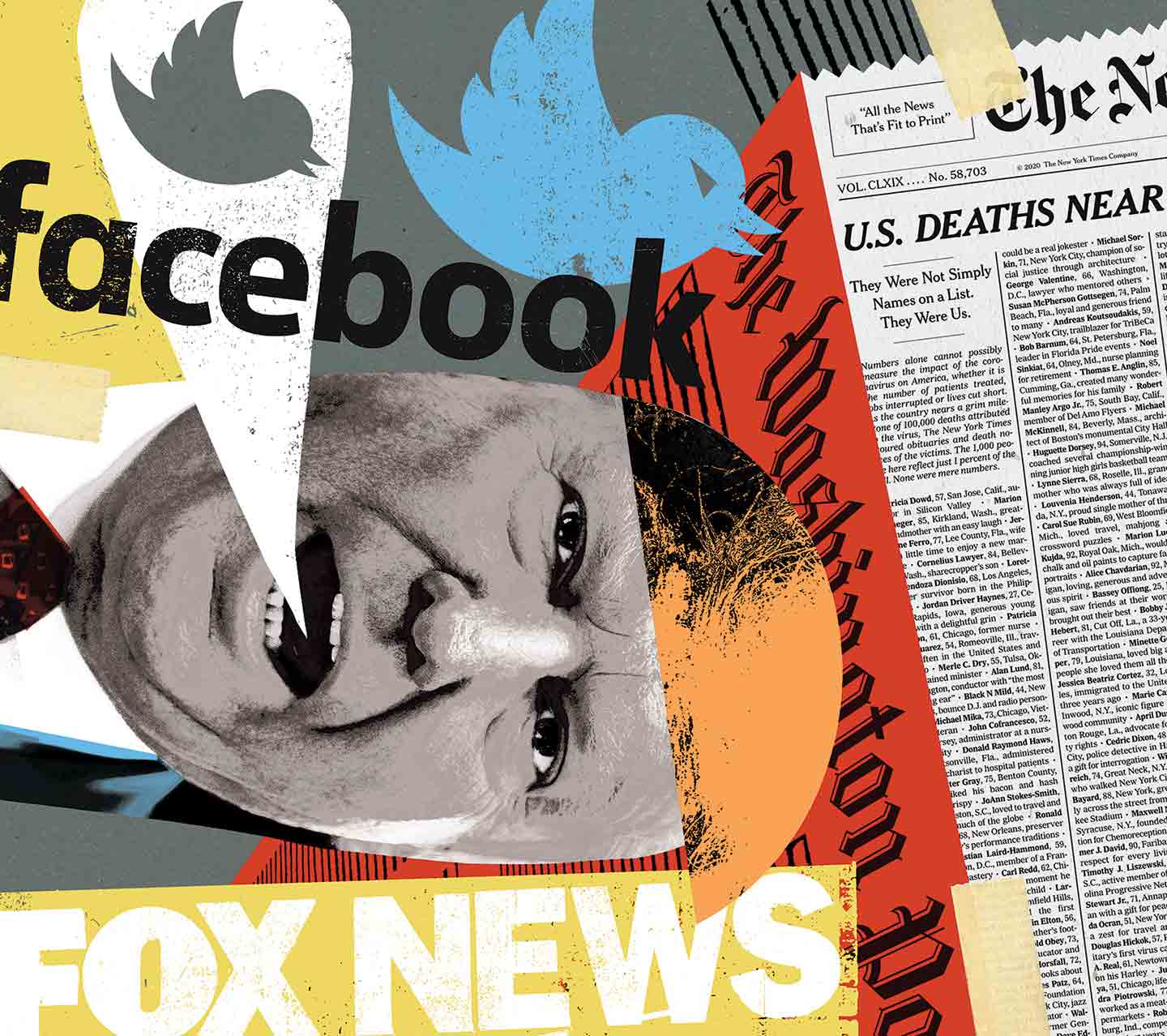

The importance of accurate information has been all too apparent during the Covid-19 pandemic. Besides charting the devastation of the virus, the World Health Organization has mapped a subsequent “infodemic,” a period of often dangerous and inflammatory misinformation circulating globally. This infodemic has had deadly effects. Donald Trump and Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro have denied the scale of the pandemic and then peddled false cures, leading to hospitalizations and deaths among people who followed Trump’s advice to drink bleach or take hydroxychloroquine. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi got in on the act, claiming that yoga could increase immunity to Covid-19.

The misinformation would be laughable if it weren’t so deadly. A group of economists studying the pandemic in the United States has shown that as a result of bad information, there have been higher death rates from Covid-19 among viewers of Sean Hannity, a Fox News host who downplayed the threat. Meanwhile, Republican opposition to mask wearing may have contributed to skyrocketing infection rates in the United States in July.

Many of the tools used to fight misinformation have proved inadequate. Fact-checking politicians’ statements can be haphazard, and rebuttals often arrive long after the lies have gone viral and may not reach the people exposed to them. Attempts to build trust in the media through audience engagement have been limited in scale and remain mostly local. Twitter and Facebook have attempted to crack down, removing damaging accounts and pointing people to trustworthy sites with reliable information, but both companies have been slow to act. Their business model, after all, is based on audience engagement and outrage, so it’s the controversial and often false information that makes them the most money. There is no financial incentive to crack down.

Reliable information is clearly needed, but journalists find themselves in a difficult position. Although they have been classified as essential workers, tens of thousands have been laid off or furloughed around the world. News audiences have risen dramatically in 2020, but sharply declining revenue in previous years—particularly from advertising—has crippled many newsrooms. Now the economic effects of the pandemic have set the stage for what some are calling a media extinction event.

This is true in the United States, where things are so bad that the Poynter Institute, a nonprofit journalism school and research organization, says it’s updating its job loss tracker almost every day. As of this writing, the institute reports that 18 local newspapers have merged, at least 1,500 newsroom staffers have been permanently laid off, a minimum of 20 publications have suspended their print editions, and at least 30 local newsrooms have closed. (Also, journalists of color are often the most likely to be laid off, as The Washington Post reported in May.) But the crumbling of news organizations is not confined to the United States; it is happening all over the world. As the Botswanan journalist Ntibinyane Ntibinyane warned in April, many African newspapers might not survive the pandemic, and the same is true in countries as diverse as Bolivia, Brazil, India, Liberia, the Philippines, and the United Kingdom.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

The desperate situation that the media finds itself in—and that we all face with it as a result—is the focus of Victor Pickard’s new book, Democracy Without Journalism? Confronting the Misinformation Society. Written before the pandemic hit, the book is all the more relevant in a world transformed by Covid-19. Among other things, it offers a critical examination of US media history, arguing that at crucial moments, a market-centered understanding of the media has undermined the public good that news outlets provide. Yet the book also offers us an important reminder that it is not too late to right this wrong by creating what Pickard calls “a permanent public news media shielded from the market.” The “current crisis,” he says, “offers opportunities for reasserting the public service mission of the press.”

Democracy Without Journalism? is the story of how the United States missed so many opportunities in the past. Pickard begins with the early years of the United States and the tension between American democracy and classical liberalism. For him, the prevailing assumption that laissez-faire politics and “capitalist competition” would best serve “democratic communication” has had disastrous consequences. Far from creating a liberal marketplace of ideas, it has resulted instead in a system dominated by powerful elites who have limited the range of political points of view, narrowed the field of reporting, and starved local news of funds.

For Pickard, the abiding faith in the market has not just impeded the flourishing of a truly free and diverse press; it has also hindered our ability to institute policies that might correct this situation. He examines areas like government regulation and monopoly control to illustrate how US policy at key points in history led to the news media’s precarious state today, and he highlights those moments when the United States might have pursued a more democratic path for journalism.

One important example for Pickard is the debate over the role of the press that took place during and after World War II. As Sam Lebovic observes in Free Speech and Unfree News, freedom of the press was viewed as “an obvious antidote to dictatorship” in the wake of the war against fascism and then in the dawning years of the Cold War. Media concentration was likewise seen as a potential danger, spawning a vigorous debate over how to regulate the news industry.

To study this threat, the Commission on Freedom of the Press was established in late 1943. Known as the Hutchins Commission (after its chair, University of Chicago president Robert Hutchins), it held numerous meetings and eventually published a report. But within the commission, analysts were divided. Media reformers wanted to break up the major newspaper monopolies, insisting that freedom from corporate control was an important part of press freedom, but they lost out to those who viewed freedom from government interference as the best way to preserve the marketplace of ideas.

The commission’s “corporate libertarian” views, as Pickard puts it, prevailed, as they did more generally in debates over government support for the media. The Federal Communications Commission, which was established in 1934, hewed to the position that it should play a limited role in regulating the press. By excluding the possibility of government-supported media reporting in the public interest, the FCC left those who wanted to protect journalism fighting with one hand tied behind their back.

Pickard notes that this did not have to be the case. From the nation’s earliest years, the federal government supported the news media in indirect ways. Drawing on the work of Richard John, who examined how the founders viewed the post office as central to the nation’s information infrastructure, Pickard argues not only that the Hutchins Commission was a missed opportunity but also that the debate showed a considerable misunderstanding of the government’s role in the past. Newspapers and magazines, he writes, have long enjoyed various government subsidies, including most obviously from the Postal Service, where over time they accounted for the majority (by weight) of what the post office shipped and delivered. In fact, if one added up all the discounted postal rates that newspapers and magazines have received since the 18th century, the sum would amount to several billion dollars.

Thus government subsidies were an important part of the news industry from its earliest days. The embrace of a corporate libertarian position did not hew to past practices; instead the refusal to invest in the press only marked an abdication on the part of the federal government—one that created an opening for further monopoly control.

Without government funding or regulation, newspapers and broadcasting companies became dependent on advertisers and wealthy owners, setting the stage for the fiercely partisan reporting we see today from the Sinclair Broadcast Group, Fox News, and even more extreme outlets.

The American fidelity to laissez-faire created another problem: As a result of free-market ideology, newspapers and magazines are seen not as a public good but instead as commodities to be sold for profit by private companies outside the control of public institutions.

In Democracy Without Journalism? Pickard outlines a series of proposals to create a more robust news media in the United States and thus a more democratic society. He calls for the creation of a fund that would support local journalism, especially in the country’s growing number of news deserts, and for stronger privacy restrictions and more regulatory bodies to prevent further consolidation in the industry.

All of these policies are perfectly reasonable and, as Pickard shows in the book’s sections on other countries, are currently enjoyed by many other parts of the world. But he also recognizes that the notion of a government-funded media system remains anathema to many in the United States—especially (but not only) to Republicans, who have long opposed an expansive role for the FCC and government regulation of huge media companies. In his book’s last chapters, Pickard surveys many of the ongoing battles between Republicans and Democrats over the role of the FCC, as well as the prospect of more public subsidies for newspapers, radio, and television.

Instead of effective corporate regulation, the Fairness Doctrine—the 1949 replacement for the Mayflower Doctrine, which constrained broadcasters from editorializing—had long served as a consolation prize for media reformers. It required broadcasters to cover socially important issues and to fairly present opposing sides. But even that proved too much for Republicans, who repeatedly framed the policy as an attack on broadcasters’ free speech until it was revoked by Congress in 1987.

Pickard considers the battle over public television and radio, which resulted in many fewer institutions (and with far less money) than media reformers originally envisioned. And even after it became clear that the 2008 financial crisis was destroying America’s newspapers, the federal government and the FCC in particular chose to do basically nothing about it. Insisting in 2011 that “government is simply not the main player in this drama,” the FCC concluded that all the media needed was more transparency, increased government advertising, and support from philanthropists. These recommendations were assailed at the time as falling far short of what was required. More than 120 news outlets were shuttered in 2008 and the first three months of 2009; others shrank, and an estimated 13,000 newspaper jobs were lost in 2008, followed by another 15,000 in 2009.

Since then, the growth of Big Tech has further confounded the industry. Unregulated, Google and Facebook have taken away what little advertising revenue remained in the hands of newspapers and magazines. Social media platforms such as WhatsApp and Twitter have spread vast amounts of misinformation, sparking violence and killings in India, Mexico, Myanmar, and Nigeria, to name just a few examples.

Pickard has spent years working with the media activists at Free Press, a nonprofit organization that supports independent media and has called for the major social media platforms to be taxed more aggressively, and in Democracy Without Journalism? he draws from this experience to make his case for greater government investment in media outlets. A dedicated tax on online advertising could raise as much as $2 billion for independent journalism, he notes, but he quickly adds that this should be only a start. What the country needs is a public media fund of about $30 billion annually. It would be paid for by taxing media and platform monopolies and repurposing existing subsidies, with the money flowing directly to a set of genuinely public media institutions.

Pickard’s public media fund is a bold idea, and it has already been adopted in some places on a more local scale. In New Jersey, for example, Free Press was able to persuade the state government to set aside funds for the Civic Information Consortium, which has a mandate to revitalize local media, particularly in “underserved, low-income areas and communities of color.”

The New Jersey program, Pickard argues, could be extended to most states to help create public radio and TV stations, and the Los Angeles Times recently put forward a raft of proposals as well, including making it easier for news outlets to convert to not-for-profit status, as The Salt Lake Tribune did in 2019; low- or no-interest loans for communities that want to set up locally owned news outlets; and tax deductions for subscriptions to nonprofit news sources. But all of these proposals still require political will—and right now, neither the Democrats nor the Republicans have embraced them.

Some of the most inspiring sections of Democracy Without Journalism? are those that discuss the news media outside the United States where a political will has been present. As Pickard observes, many countries have secured quality independent journalism through public funding and regulation. Norway and Sweden subsidize the press, as do Australia, Canada, Germany, and the UK. The BBC proposed the Local Democracy Foundation and is now funding journalists to cover local council meetings that would otherwise go unreported. Canada even gives tax credits for digital news subscriptions.

A publicly subsidized news industry would not only allow the United States to keep pace with many of these countries; it would also clarify how the news itself is a public good. There is yet another reason to do so: Regulation and funding can make it possible for the views of local communities to be heard, which are often drowned out by the corporate-backed, syndicated voices of right-wing figures like Hannity and Laura Ingraham.

Pickard’s proposals may seem hard to realize, but public media systems all over the world show they can be achieved. As Pickard reminds us, if we don’t take steps now to safeguard journalism, then democracy, such as it is, may not survive the present.