My great grandmother Kitty Levake Adams had deep roots in rural southwestern Wisconsin. But after my great grandfather passed at the end of World War II, she moved up to Madison, where she lived for the last 15 years of her life. Every Election Day, however, she would return to her hometown, Blue River, and work the polls.

She believed it was her democratic duty. And she knew it was the single best way to keep up with all the news from the town where she had spent most of her life. I share her sensibility and that’s one of the reasons why, despite all this year’s encouragement of early voting, I chose to cast my ballot in person on Election Day.

Election Day in small towns like Blue River, and in urban neighborhoods across this country, has always been about more than voting. Of course, presidents and governors and myriad state and local officials are chosen. But there’s more to it than that, as Kitty Levake Adams knew.

For her, Election Day was the moment when her village of 400 came together for a sort of civic celebration that began shortly after dawn and continued well into the evening. People came to vote and stayed for the conversation. They brought main dishes and desserts for the poll workers. They checked back in the evening to see who had been elected in a town where contests for village posts were congenial and good-spirited, and where Democrats and Republicans, Progressives and Socialists all played their parts in the communal life of a town that was just a bit too small for maintaining partisan grudges.

That did not mean that party politics and ideological stances were neglected. The Adams family embraced Robert M. La Follette’s progressive vision, which first found expression in the Republican Party but eventually served as the basis for the Progressive Party that broke the grip of the two major parties in the mid-1930s. My great grandfather, who served for many years as village president of Blue River, filled his fall days and nights with campaigning for “Fighting Bob” and various and sundry other La Follettes, and for his radical friend John Blaine, the three-term governor of Wisconsin and US senator who hailed from down the road in Boscobel.

But on Election Day, the campaigning ended and Kitty and her friends took charge. They oversaw the voting and the counting of ballots, and no one messed with them. They arrived early, got the ballots and the ballot box in place, and then opened the doors for a long day of democracy. It was never all that busy in Blue River, There was plenty of time to talk about farm prices and work, weather and grandchildren.

My great grandmother wasn’t about to give up on the social event of the season. So, after she came up to Madison, she would cast her vote in her new hometown and then head out to Blue River to help out with the primaries and general elections of the spring and fall. After she had settled in on Madison’s east side, she was informed that she shouldn’t be running elections in Blue River. Fair enough, she said. Then Kitty would just head back to the village hall and hang out with her friends on Election Day.

I thought of all this family lore as I was preparing to vote in this year’s bitterly contested presidential election. I started writing in March about the threat to democracy that the coronavirus pandemic posed, publishing some of the first articles on the need to improve structures for voting by mail. Throughout this fall’s election season, I’ve been an ardent advocate for making it easy for everyone to vote in the way that is healthiest and safest and easiest for them. I’ve helped friends with busy schedules and family members with preexisting conditions to navigate the absentee voting process. And, of course, I’ve been furious with the partisan machinations of President Trump and the right-wing partisans who have sought to make that process more difficult—with legal challenges to voting rights that are best understood as voter suppression.

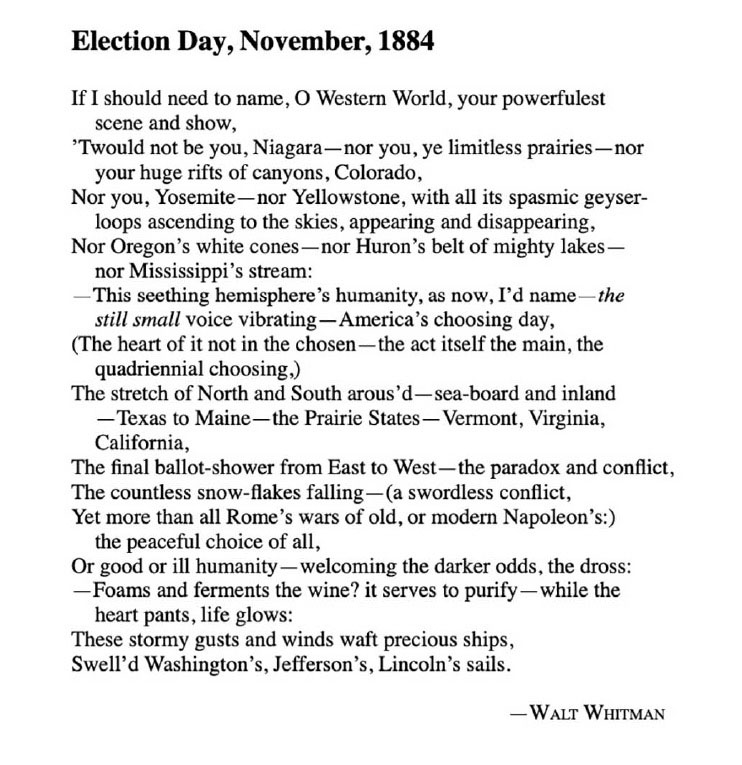

But, like my great grandmother, my grandmother and my mother, I have always delighted in the rituals of Election Day. So, despite it all, I cast my ballot on Tuesday afternoon at the neighborhood school. My daughter Whitman, Kitty Levake Adams’s great great granddaughter, was working the polls. And I thought of one of my favorite poems by my daughter’s literary namesake: