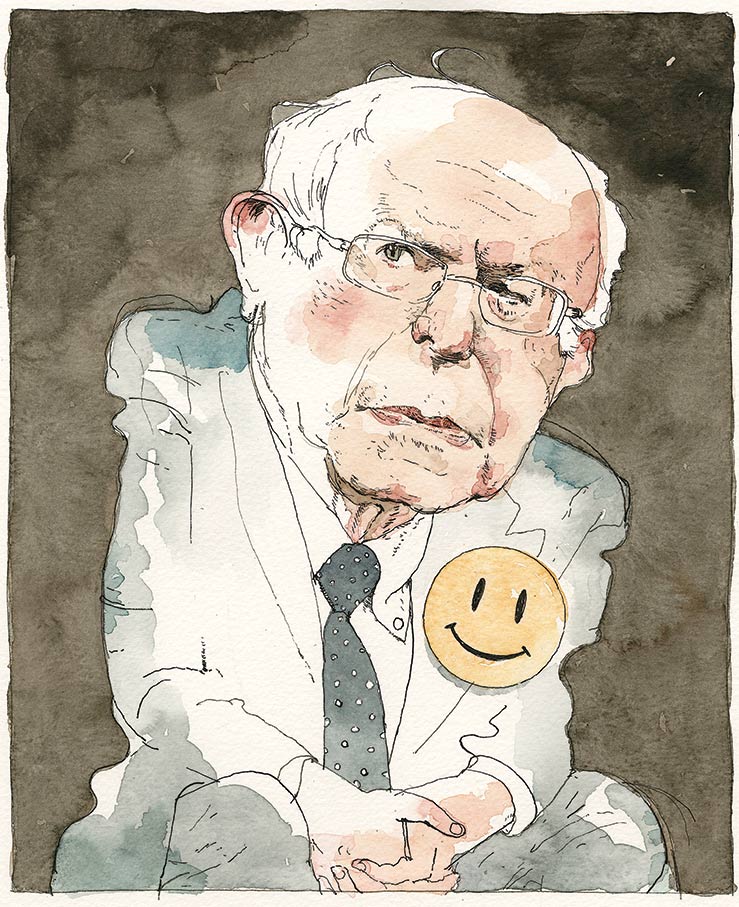

Burlington, Vt.—Bernie Sanders does not want to be mistaken for an optimist. “I’m a glass-half-empty kind of guy,” he grumbles, as he works his way through the stacks of budget documents that are strewn across the desk in his spartan office on the third floor of a 123-year-old red-brick building on the north end of downtown Burlington. That’s the image he’s fashioned for himself across five decades of political campaigning, and he’s comfortable with it. But the thing is, for all his genuine cynicism about the political and governing mechanisms he has long decried as corrupt, Sanders keeps erring on the side of what the writer Rebecca Solnit refers to as “hope in the dark.” He’s willing to take chances in order to push the boundaries of the possible: to run for and secure a seat in the US Senate as an independent, to bid for the presidency as a democratic socialist, to propose a political revolution. So it shouldn’t come as a surprise that—from his recently acquired position of prominence and power as chair of the Senate Budget Committee—Sanders has launched a new campaign to achieve “the most progressive moment since the New Deal.”

For Sanders, this is an urgent mission that is about much more than the proposals outlined in the budget plan he joined Senate majority leader Chuck Schumer in outlining on August 9. It is a necessary struggle to address the simmering frustration with politics as usual that Donald Trump and his Republican allies have exploited to advance an antidemocratic and increasingly authoritarian agenda.

“What we are trying to do is bring forth transformative legislation to deal with the structural crises that have impacted the lives of working people for a long, long time,” Sanders says. “Whether it is child care, whether it’s paid family and medical leave, whether it’s higher education, whether it is housing, whether it’s home health care—we’re an aging population; people would prefer to get their care at home—whether it is expanding Medicare to take care of dental and eyeglasses and hearing aids, what we are trying to do is show people that government is prepared to respond to their needs.”

That’s an echo of the big-government-can-do-big-good message that Sanders has carried for the past five decades through all of his campaigns. Yet now, for the outsider who has become a somewhat uncomfortable insider, the message has found its moment. He is heading to the White House to consult with President Joe Biden about strategy. He is taking on what Politico describes as “a central role in the Democratic caucus” of a chamber where critics once dismissed him as a left-wing scold. He is appearing with Schumer to declare, not from the sidelines anymore but from the eye of the media maelstrom, that “the wealthy and large corporations are going to start paying their fair share of taxes, so that we can protect the working families of this country.”

Bernie Sanders hasn’t changed—amid the budget documents arrayed across his desk in the old Masonic Temple building in Burlington is a book on Eugene V. Debs, the labor organizer and Socialist Party presidential candidate whom Sanders has revered for decades. But Washington has. Suddenly, the democratic socialist with ideas that were once labeled “radical” is being taken seriously by partisans who would not nominate him for president but who are ready to embrace substantial sections of his agenda. Biden takes the counsel of his former rival, often on the phone, sometimes in private meetings in the Oval Office—one of which secured presidential support for Sanders’s proposal for a sweeping build-out of the Medicare program to include full coverage of dental, vision, and hearing care.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

“The most difficult thing in politics and governing is to be pushing ideas that most people in power aren’t ready to accept. But when people in power recognize that those ideas are popular, and that they’re necessary, everything changes,” says Ben Jealous, the former NAACP president and Maryland gubernatorial candidate who now serves as president of People for the American Way. Jealous, who delivered a stirring address at the 2016 Democratic National Convention on behalf of Sanders’s first presidential bid, says the senator has entered a new stage in his long political journey. “I think that what happened is that Bernie went out and talked about these ideas. He showed how appealing they are, and that had an impact,” Jealous explains. “Now people in power—the president, members of the Senate—are listening.”

When I spent time with Sanders in Burlington in July, as he was busy building support for a budget plan, the senator was making calls and receiving them at a daunting rate. From Cabinet members and progressive allies in the movements he has always aligned with. From White House aides and moderate senators who needed just a bit more cajoling. He was surrounded by spreadsheets, priority lists, and policy proposals, yet he did not seem harried. To the extent that this hyperactive 79-year-old can be calm, he was. Or, at the least, focused.

Sanders recognizes that he can define only so much of the process.

He was angling for a $6 trillion budget plan, and what he ended up with is a $3.5 trillion package. But that’s still, as the senator says, “a big deal.” The plan anticipates funding to expand Medicare, federal paid family and medical leave protections, and major investments in child care, including an extension of the groundbreaking child tax credit that was included in the American Rescue Plan; to reduce the cost of higher education and make community college free; to develop initiatives to reduce reliance on fossil fuels; and to return to old-school progressive taxation that really does “tax the rich.” Sanders ally Ro Khanna, the Democratic representative from Silicon Valley, says that if anything akin to this budget is adopted, “it will be a historic shift in how we view the role of government.”

That’s what Sanders is counting on—not just for the purposes of budgeting but for the future of American democracy.

“Why it is imperative that we address these issues today is not only because of the issues themselves—because families should not have to spend a huge proportion of their income on child care or sending their kid to college—but because we have got to address the reality that a very significant and growing number of Americans no longer have faith that their government is concerned about their needs,” says the senator. “This takes us to the whole threat of Trumpism and the attacks on democracy. If you are a worker who is working for lower wages today than you did 20 years ago, if you can’t afford to send your kid to college, etc., and if you see the very, very richest people in this country becoming phenomenally rich, you are asking yourself, ‘Who controls the government, and does the government care about my suffering and the problems of my family?'”

Sanders argues that restoring faith in government as a force for good is the most effective way to counter threats to democracy. The senator, who has opened up more and more in recent years about his own family’s history as Jews who fled Europe but lost most of their relatives in the Holocaust, reads a lot these days about the rise of fascism in pre–World War II Europe, and he is highly engaged with conversations about contemporary threats to democracy. This is not just a reaction to what happened on January 6, when Trump incited an insurrection by supporters of his effort to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election. It is a concern Sanders has been speaking to with increasing urgency over the past several years.

Sanders devoted much of his speech at the 2020 Democratic National Convention to the topic. “At its most basic, this election is about preserving our democracy,” he said. “I and my family, and many of yours, know the insidious way authoritarianism destroys democracy, decency, and humanity. As long as I am here, I will work with progressives, with moderates, and, yes, with conservatives to preserve this nation from a threat that so many of our heroes fought and died to defeat.”

Almost a year later, on a summer afternoon in Burlington, I ask Sanders about a reference he made in that speech to Trump refusing to leave office and about even blunter expressions of concern he had made in conversations we had in the fall of 2020. “If you recall, I came pretty close to predicting exactly what Trump would do in terms of his response to the election,” he says. “I asked people to think about whether he was going to accept defeat and say, ‘Oh, gee whiz, good campaign. Congratulations, Joe. How can I help you?’ That wasn’t going to happen.” And, of course, it didn’t.

Since January 6, Trump has doubled down on his false narratives about the election, and his allies in legislatures across the country have made an ongoing assault on democracy central to their political project. “I take this threat of authoritarianism and violence very, very seriously,” Sanders says. “I don’t think that January 6th is a one-time situation. We’re seeing the growth of militias, and…even in rhetoric, the talking about violence from Trump on down.”

Sanders voted to convict Trump of high crimes and misdemeanors—twice—and has evolved into an ardent supporter of efforts to overturn the filibuster in order to pass the democracy-defending For the People Act and the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act. Those reforms are necessary, he says, to preserve democracy. But so, too, he argues, is the proposition that government can solve seemingly intractable problems and make the lives of working-class people dramatically better.

“If we do not restore faith on the part of the American people in their government, that we see their pain and we respond to that pain, that we have the courage to take on powerful special interests—if we do not do that, more and more people are going to drift toward conspiracy theories, authoritarianism, and even violence,” Sanders explains. “So I think that this is a pivotal moment in American history.”

Put that way, the responsibility is a daunting one. But Sanders got comfortable with daunting tasks a long time ago.

The Brooklyn expatriate mounted his first campaign for elected office—an audacious bid on the ballot line of a radical third party for the Senate seat he would eventually win in 2006—50 years ago next January. And he has never stopped campaigning. A willingness to take defeats as well as victories, along with a refusal to abandon his democratic socialist faith in the transformative power of a government that is harnessed in the service of humanity, has led election rivals and media commentators to portray Sanders as a gadfly. Yet the thing that political partisans and pundits often miss is the extent to which he has proven himself as a politician and a legislator.

As an independent member of the House from 1991 to 2007, and as a senator since then, Sanders earned a reputation for forging left-right coalitions and for masterfully amending pieces of legislation. He has shown a skill for leveraging committee chairmanships to achieve major goals. He did so during Barack Obama’s presidency when, as chair of the Senate Veterans’ Affairs Committee, he led a successful bipartisan effort to strengthen the VA health care system by authorizing 27 new medical facilities and providing $5 billion to hire more doctors and nurses to care for veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. And he has continued to do so since he took over as chair of the Senate Budget Committee in January.

When I interviewed Schumer recently, he praised Sanders for his role in passing the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan using the Senate’s arcane reconciliation process, which allows spending measures to advance without being blocked by a filibuster. Schumer, who relied on Sanders in the relief act fight and who will again rely on him if and when reconciliation is used to approve the budget, recognizes the Vermonter as an essential ally. “I have always believed that government is the answer, and that I share with…Bernie,” he says, echoing Sanders on the vital importance of making government work in this turbulent time. “I believe that democracy is at risk, and we cannot fail.”

“This democracy is at risk,” Schumer adds. “But if we show people that the American dream is still alive—and the Biden plan does that in many very significant ways—we can restore and improve it.”

It sounds like Schumer gets it. Does Biden?

When I ask Sanders that question in Burlington, he doesn’t hesitate. “Yes! Interestingly enough, I think he does,” Sanders replies. “When he talks about the competition between democracy and authoritarianism all over the world, I think he is talking about that. I do believe he understands this.” The challenge, of course, is to move from understanding to action. “It’s not enough to talk about it. You’ve got to act.”

That’s where Sanders comes in. He is already campaigning for the president’s new budget in ways that Biden and Schumer cannot. In his bids for president, Sanders did not just build a name for himself, as most candidates do; he built a movement that pushed progressive ideas about governing to the forefront. To a far greater extent than any campaigns since Ronald Reagan’s in 1976 and 1980, Sanders’s campaigns transformed the way people think about government. While Reagan convinced a great many Americans that “government is not the solution to our problem, government is the problem,” Sanders convinced a great many Americans—especially younger ones—that Reagan was wrong. “There’s been a real change in how people think about government,” says the law professor and author Jennifer Taub, “and Bernie was a part of that.”

Now, just as he did on the campaign trail, Sanders must get people nodding their heads and saying, “Yeah, we can do that,” this time about a budget that proposes to meet human needs by taxing billionaires and multinational corporations. He won’t have to work alone; he’s got a growing cadre of allies in the House, and he’s earned the respect of influential centrists, such as Virginia Senator Mark Warner. The reconciliation project will still be challenging, as skeptical comments about the budget plan from Democratic senators like Arizona’s Kyrsten Sinema offer a reminder of how difficult it will be to maintain the unity that is required. But this is work for which Sanders remains uniquely well prepared. When he campaigned for the Democratic presidential nod in 2020, a Quinnipiac poll suggested that voters saw him as the most honest and forthright candidate. He retains a level of trust and personal popularity among people who don’t put a lot of faith in politicians.

One afternoon in Burlington, we took a walk through the city. Or, to be more precise, a series of stops. Sanders is a fast walker, but he was constantly stopped by locals and by visitors from Idaho and Colorado and Texas and other states across the country. They all knew who the senator was. They all felt they could approach him. They all wanted to express their gratitude.

“Thank you for taking on the corporations.”

“Thank you for talking about taxing the rich.”

“Thank you for telling the truth.”

“Thank you for being there for us.”

Block after block, until we got to the edge of downtown, Sanders stopped and talked for a moment, smiled for the selfies, and moved on. Sometimes he would say, “I’m going to need you. We’ve got some big fights ahead of us.” Invariably, the response was: “Tell us what we’ve got to do.”

The fierce loyalty of his supporters, and the openness to his message from Americans who might not have supported his presidential bids but whose respect he’s won, makes Sanders a powerful player in Washington. He is in a better position than anyone else in the Senate Democratic Caucus to argue the populist case for big budgets and bold governance. Democrats, including the president, know they need Sanders. That gives him leverage that he has never had before. But with that leverage comes responsibility. I covered Sanders as a presidential candidate, and I saw how hard he worked with activists across the country to build movements for economic and social and racial and climate justice. Now he’s campaigning to turn that movement politics into a governing agenda. It’s a different kind of pressure, a different level of stress, and for Sanders, who has always preferred grassroots campaigning to roaming the corridors of power, it’s not as fun. But this glass-half-empty guy is not about to miss the chance to pursue a new New Deal moment and, in so doing, to renew the promise of American democracy. “If you’re asking me was I born to be an inside-the-Beltway player, I was not. I would much prefer to speak to a rally of 25,000 people than get on the phone and talk to some of my colleagues. That’s true,” he says, as he leans into the next campaign. “But this is my job. This is where all my energy is at the moment. I’ve got to do it, and I will do it.”