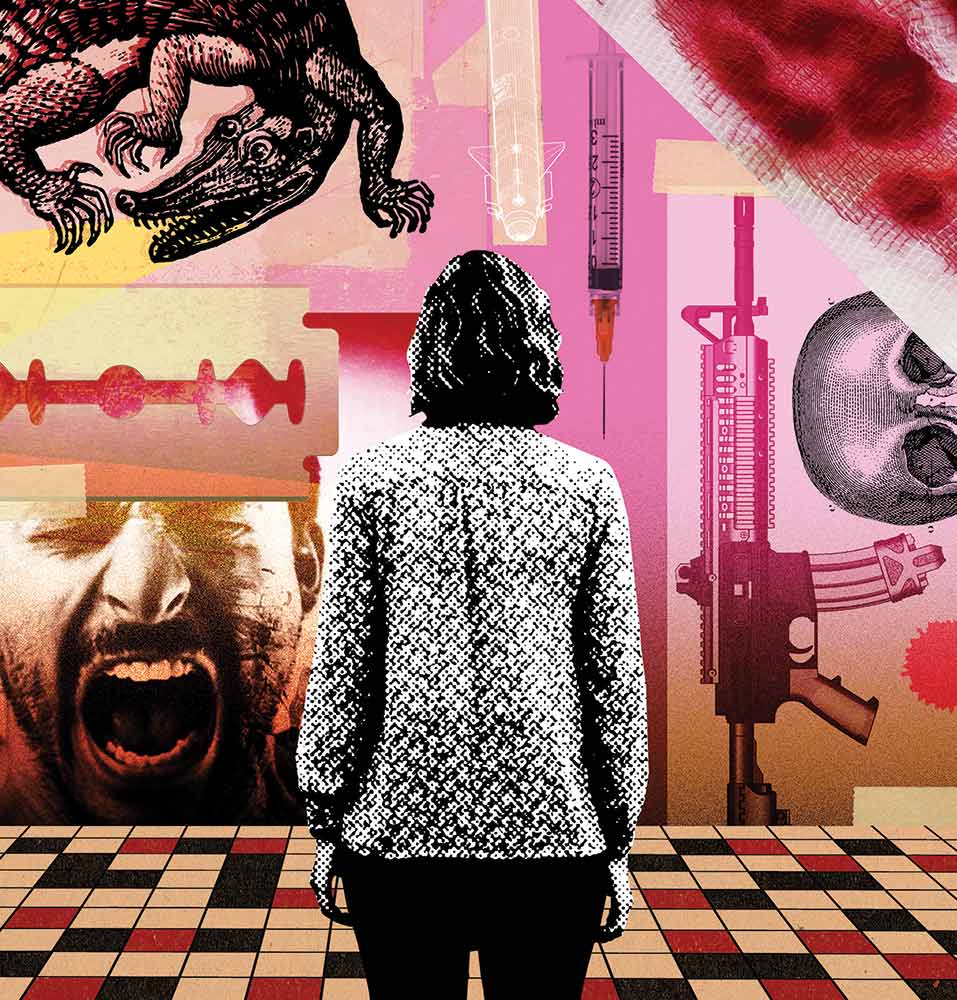

In the circus of shitty jobs that tech companies have created in a few short decades—from Uber drivers to Mechanical “Turkers”—the content moderators are the most damned: They’re the sin-eaters, the scapegoats in the wild. They suffer so that we, the rest of humanity, may go about our days, scrolling our feeds, shielded from the vast magnitude of human depravity in this world, at least as it is documented and shared in social media images.

You know the stories by now. A group of people, poorly compensated, are arranged in a call center environment as contract workers for a platform you’ve definitely heard of, in a nondescript office somewhere, likely in the Philippines or the American Southwest. At their desks, on a screen, they watch footage of people being raped or killed, of violence committed against children and animals—they see it and scrub the footage from the platform. The workers’ mental health suffers, and PTSD plagues them long after the last post they filter.

That we know these stories at all is a relatively recent development. There had been a few earlier reports on the practice, but a feature by Adrian Chen for Wired magazine in 2014 was uniquely galvanizing. In the story, Chen pointed out that a major problem for content moderators was that most people didn’t know about their existence. Chen’s story, which considered the psychological toll on these workers, cited research by Sarah T. Roberts, a UCLA professor and codirector of the Center for Critical Internet Inquiry, who published a book on the subject, Behind the Screen: Content Moderation in the Shadows of Social Media, in 2019. Further reporting in 2019 by Casey Newton in The Verge revealed how day-to-day labor exploitation—bathroom breaks monitored, workers surveilled by management while surveilling the lives of others—stacked enormous workplace anxiety on top of the trauma of the work itself. Raising public awareness about an issue like this is no small feat—but now that we know about content moderation, what are we supposed to do about it?

We could ask the content moderators themselves, but despite the various articles and books, their identities and lived experiences largely remain a mystery. There’s an absence of first-person essays, memoirs, and personal accounts; we hear from them instead through anonymous quotes and as unnamed sources. Who are they? How did they end up taking this job? What do they do for fun? Is it hard to hold on to friends and maintain relationships with such a traumatizing job? Another question that people might ask is: What do they actually see?

That’s what everyone asks Kayleigh, the narrator of Hanna Bervoets’s novella We Had to Remove This Post. Kayleigh’s aunt, her therapist, and her new coworker all want to know what it’s like working as a content moderator for Hexa, a subcontractor for a major social media platform. “People act like it’s a perfectly normal question,” Kayleigh says, “but how normal is a question when you’re expecting the answer to be gruesome?”

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

With its conversational tone and sly, somewhat withholding narrator, We Had to Remove This Post reads like a one-woman play—which makes sense, since Bervoets is a playwright in addition to the author of several novels exploring subjects like reality television, bioethics, and toxic fandom. The novella, the first work by the Dutch writer to be published in English, debuted in the Netherlands last year with a print run of over 600,000 copies. It is written as Kayleigh’s unofficial testimony to a lawyer assembling a case against the unnamed social media company. Kayleigh now works at a museum. Everyone, she thinks, including the lawyer, has a voyeuristic interest in her experience, while assuming the worst about her mental state: “I can’t help but suspect a certain amount of lurid fascination, an urge that compels them to ask but that can never be fully satisfied.” The chapters that follow reveal the gap of understanding between these workers and the public, though not always as the author intends.

Content moderation is beset by certain contradictions that invite such a narrative. It is care work—workers screen material for the well-being of others—that demands apathy or a high level of tolerance, as Roberts has written, for “images and material that can be violent, disturbing, and, at worst, psychologically damaging.” By that measure, Kayleigh is an ideal character to plumb social media’s depths: She’s brusque but not unemotional, reserved but not without private longings.

The book is partly an office novel and partly a chronicle of the breakdown of a relationship. Kayleigh and Sigrid, another moderator, get close during an office happy hour and soon move in together. Their relationship is propped up by tacitly understood but carefully established boundaries between life and work. “I never asked her what she dreamed about,” Kayleigh recounts. “I had some ideas. But they were all the things I’d rather not think about, either, at least not at night, with the lights off and our desks at Hexa miles away.”

But as the job grows more grinding and more harrowing, Sigrid asks Kayleigh for some emotional support: Who else understands the horrors she’s seen? Sigrid is haunted by a girl who posted pictures of self-mutilation and appears to have died by suicide. Sigrid forwarded the content to the company’s child protection department. “You did what you could, baby, didn’t you?” Kayleigh offers in response. But her attempt to console Sigrid is insufficient.

As it happens, Kayleigh and Sigrid aren’t the only people hooking up at the Hexa office. The content moderators rendezvous so frequently in the lactation room that the company removes the lock from the door. It’s a peculiar detail that sticks out and calls for additional context. An explanation can be found in Newton’s story for The Verge. “Desperate for a dopamine rush amid the misery,” he reported, Facebook moderators were often found having sex in the lactation room, so “management removed door locks from the mother’s room and from a handful of other private rooms.”

A turning point in the novel also comes directly from Newton’s article. The Hexa staff observe a suicide about to happen—not on the screen but out the office window; there’s a man standing on the roof of the building next door. Yes, they have witnessed scenes like this many times before, albeit mediated by their desktop monitors—but when it’s happening so close in real life, it’s visceral. The care that comes through in the author’s depiction of Kayleigh and Sigrid’s delicate relationship falters here. Sketched out briefly in this short book of just over 100 pages, the event becomes, in Bervoets’s telling, a muddled and not particularly original observation that the screen blunts emotions that people experience more vividly IRL. “That whole time it was like I’d been watching a video,” Kayleigh reflects later. Bervoets isn’t pilfering Newton’s work here; she lists him in a “Selected Sources” section at the back of the book, along with Roberts and Chen. The trouble is that, even when she borrows anecdotes from these sources, Bervoets’s fiction lacks stakes: Kayleigh, unlike most real-life content moderators, isn’t living paycheck to paycheck.

The Verge feature was shocking not because it told us what content moderators see and do—Roberts, Chen, and others had already revealed that much—but because it exposed the outrageous demands these workers faced in addition to the trauma. Newton wrote that content moderators were forced to “scratch and claw” to achieve near-perfect accuracy scores, because anyone with a score under 95 percent risked getting fired. In Arizona, the job paid $4 above the minimum wage, and the workers Newton profiled all had bills they struggled to pay.

Kayleigh seems much less subject to these dire economic conditions. From the very first pages, we see that she has landed on her feet, at a nice job in a museum, and will never have to watch a beheading video again. Bervoets has made the perplexing decision to tell this story from the point of view of a middle-class woman. Kayleigh is a landlord, too, who at one point evicts some tenants in a “polite way” from her mother’s house, which she has inherited. She has debts because she spoiled her previous girlfriend with a television, a turntable, fancy clothes, and a trip to Paris. It all sounds like the beginning of an incredibly bleak entry in the Confessions of a Shopaholic franchise.

Hexa doesn’t have to be depicted as a pressure-cooker environment, of course. It’s Europe—maybe they take the whole month of August off for vacations. But when Kayleigh’s coworkers become radicalized by the content they filter, such as Holocaust denialism and flat earth theory, in exactly the same way as the workers in Newton’s article, I have trouble believing it. Who are these workers? Why did they take this job? Why don’t they get jobs in museums instead—or anywhere else? We Had to Remove This Post doesn’t attempt to answer these questions or complicate the examples it draws from prior reporting or add more narrative or psychological texture, which means it only echoes the public awareness that Bervoets’s sources had already achieved. The public knows that content moderation is happening. It’s addressed, even joked about, in Kimi, Steven Soderbergh’s most recent film.

Kimi, which was released earlier this year, is about a white-collar tech worker, Angela (played by Zoë Kravitz), who monitors the feeds of an Amazon Alexa-like voice product, cleaning its data and coding automated filters. “Trust me, I know bad—I used to moderate for Facebook,” Angela tells a colleague in a video call from her spacious Instagram dream of an apartment. In less capable hands, this brief hint at a backstory might not have added up. Clearly, Angela didn’t work in an environment like the one in Newton’s article. But the character’s wealth does open up a new dimension to critique. For any worker, making bank is preferable to a few bucks above minimum wage, but what is fair compensation, anyway, when we’re talking about a job that shouldn’t exist?

In Kimi, Soderbergh finds a common thread between the horrors that content moderators are exposed to and the trauma of a drone pilot: Surveillance heightens their distress; the distance and inability to intervene create an enduring sense of guilt. Another approach to the subject of content moderation, taken by Sam Byers in his 2021 novel Come Join Our Disease, is to drag the reader in by their “lurid fascination” and force them to confront it. In the novel, a tech company recruits a homeless woman named Maya to work as a content moderator, and she then struggles with the transition from unemployment to the world’s most brutal office job. “This was a world that had spat me out with no hesitation or remorse,” Maya says. “Now it accepted me back without interest or apology. In doing so, it caused a new kind of vanishing.” To be a success in this job is to be invisible, just as Maya was in the encampment where she lived. In the graphic and revolting descriptions that follow, Byers undermines the fictional social media company’s expressed goal: “When we do it well, no-one even knows that what we do needs doing.” The novel reminded me of a quote from a moderator in one of Chen’s reports, who compared his position to a “sewer channel and all of the mess/dirt/waste/shit of the world flow towards you and you have to clean it.” None of this makes for a pleasant reading experience, but to Byers’s credit, that is the point.

“There in the Albuquerque foothills, we toiled in a row of gray pods like the hundreds of others lining the call center. Photographs of nature scenes and slogans like ‘There is no “I” in Team’ dotted the walls.” That’s Rita J. King writing about the time she worked as a content moderator for AOL, and the vulgar material she helped filter from its now-defunct chat rooms, in a cover story for The Village Voice in 2001. (Yes, the job has a history older than MySpace.) King’s story stands out, after all these years, because it was written by someone who has done this work: a voice backed up by experience, not just a quote that proves a human was there. In a more recent account, published in 2019 by The New Republic, Josh Sklar, a former content moderator at Facebook, points out that the media dwells on the “misery porn stuff” without noting the workers’ “actual thoughts about their job, beyond that they hate it. I wish it was content moderators talking about this.” In this way, a project like We Had to Remove This Post risks speaking over the actual workers: It never transcends the “misery porn,” the very “lurid fascination” that Kayleigh dismisses. There’s a mismatch between the author’s engaging style and the subject, which she fails to elevate—Bervoets’s imagination stops where the reporting she draws her inspiration from ends.

Perhaps, by listening to these workers, we’d end up with fewer screwy assumptions about their work and lives, such as that it’s possible to shop your way down to hell. Instead of asking what they’ve seen, a better question—and one that fiction like this might seek to resolve—is: What do social media content moderators actually want? Respect and resources—health insurance, mental health care, food, housing, child care, better pay—would be my guess. But that’s not what Kayleigh the polite landlord lacks, and so we are still left wondering.

Another good question is why we need these content moderators to begin with. In the reportage, and in all of Boeverts’s sources, there is more than enough evidence to conclude: If the torture of its workers is an intrinsic part of the system, then it’s Facebook that has to die (or TikTok or YouTube—kill ’em all).