“When I came to prison [in 1993], an officer told me the only way I would leave is in a pine box,” said 51-year-old Eileen Huber. “At the time, I believed him. I don’t believe that anymore.”

Huber is one of nearly 56,000 people sentenced to life without parole, and one of nearly 204,000 (or 15 percent of the US prison population) serving a sentence that exceeds natural life expectancy. Advocates call these extreme sentences “death by incarceration.”

The United States is an outlier for such excessive sentences. Of the 193 United Nations member states, 155 prohibit life-without-parole (LWOP) sentences. In Europe, only 10 countries permit sentences of life without parole; in Latin America, only four countries still mete out life without parole.

Now, US advocates are turning to the United Nations. On September 15, seven organizations from around the country submitted a complaint to several UN special rapporteurs (human rights experts) charging that the United States’ extreme sentencing, including life without parole (LWOP), and other sentences that exceed life expectancy “effectively condemn individuals to death by incarceration (DBI), violate the prohibition against racial discrimination; violate individuals’ right to life; violate the prohibition against torture, and cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment; and are an arbitrary deprivation of liberty.”

The organizations—including the Center for Constitutional Rights, the Abolitionist Law Center, the Amistad Law Project, Release Aging People in Prison, the Drop LWOP Coalition, the California Coalition for Women Prisoners, and the Andy and Gwen Stern Community Lawyering Clinic at the Drexel University Law School—hope that the United Nations will declare that these sentences are not only cruel but also racially discriminatory and a violation of individuals’ right to life, family life, dignity, and liberty. They would like to see the UN recommend that the United States adopt maximum sentencing laws that include parole eligibility within a determined number of years.

Although the United Nations cannot force the United States (or any member nation) to implement new laws, its recommendations provide moral ammunition. Advocates hope that a UN recommendation will shift the ways in which lawmakers view such draconian sentences and spur legislative efforts to repeal them.

“It would provide a tool for the growing movement across the country to end death by incarceration and to correctly frame the issue as a violation of human rights,” said Bret Grote, legal director of the Abolitionist Law Center and co-author of the UN complaint.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

The US Supreme Court ruled in 2012 that mandatory sentences of life without parole for juveniles are unconstitutional. (The United States is the only country to sentence people to life without parole for crimes committed before the age of 18.) The ruling was not retroactive, which excluded thousands who had been sentenced as teenagers. This included Henry Montgomery, who was 17 when he was arrested and convicted in the fatal shooting of a white sheriff’s deputy in the 1960s. He appealed his exclusion and, four years later, in Montgomery v. Louisiana, the Supreme Court ruled that its earlier decision must apply retroactively. Montgomery was resentenced to life with the possibility of parole. In 2021, after 57 years in prison, he walked out a free man. He was 75 years old.

While 25 states have eliminated life without parole for people under 18 and another seven have no one sentenced to juvenile life without parole, many still allow life without parole and virtual life sentences for adults.

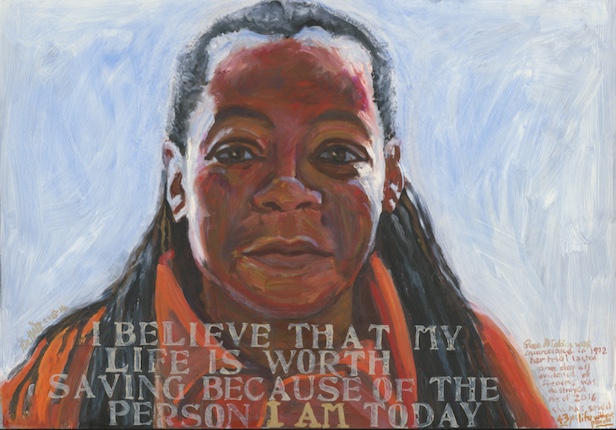

That includes Rose Dinkins, Pennsylvania’s longest-serving incarcerated woman, who entered prison in 1972. She had been convicted and sentenced to life without parole for the fatal shooting of two police officers.

In 1972, Dinkins was a 24-year-old mother with four small children. She parented through calls, letters, and visits. Now, those children are in their 50s, with children and grandchildren. Dinkins is 74 years old.

Other nations that allow life without parole use the penalty sparingly and only in the most extreme cases, such as the murder of two or more people or of a child, or murder for political, religious, or ideological reasons.

In the United States, however, several states allow courts to impose draconian sentences, including life without parole, for felony murder—a conviction which allows prosecutors to charge a person with murder even if they had not caused a death. Until recently, California was among them.

Felony murder, derived from English common-law, allows prosecutors to charge a person with murder if they participated in a felony in which a death occurred. Felony murder applies even if the person did not cause, or even anticipate, the death.

This includes Huber. “I had not taken life, but I did not have the bravery to attempt trying to stop someone I loved from killing,” she explained in her hand-written letter to the UN. Her then-boyfriend robbed and killed three different people. Huber had participated in the robberies, seeking money to buy drugs, but not the killings. She was convicted of felony murder and sentenced to life without parole.

Studies show that Black people are disproportionately arrested and sentenced to felony murder—in Cook County, Illinois, research found that nearly 75 percent of felony murder cases had a Black defendant (compared to less than eight percent with white defendants). In Pennsylvania, 70 percent of the more than 1,000 people serving life without parole sentences for felony murder are Black, nearly eight times the proportion of Black people living in that state.

In 1983, California’s state Supreme Court called felony murder “a barbaric concept that has been discarded in its place of origin.”

That place of origin, England, abolished felony murder in 1957. Since then, so have its former colonies of Canada, Ireland, and India, as well as Hawaii, Kentucky, Massachusetts, and Michigan.

In 2018, California lawmakers introduced SB 1437. It eliminated felony murder for defendants who did not kill, intend to kill, or act with reckless indifference to human life. (The person would still be prosecuted for the felonies in which they participated.) The bill was signed into law that year and made retroactive.

Between 2019 and 2021, 386 people were resentenced. The following year, the law was expanded to include those who were convicted of attempted murder and those who had pleaded guilty to manslaughter to avoid the harsher penalty if convicted of murder. Another 88 people were resentenced during the first six months of 2022. Others, however, were less fortunate, but no one tracks these numbers.

Huber applied for resentencing in 2021. The court denied her, stating that she had shown “reckless indifference to human life.” Huber is appealing that denial.

As the complaint notes, repeatedly, extreme sentences do not account for people’s maturation and change behind bars and instead fix them forever in a single moment.

“Isn’t part of the human experience learning from mistakes and becoming better?” wrote Robert Labar, Vernon Robinson, Charles Bassett, and Terrell Carter, who have been sentenced to life without parole in Pennsylvania. (Carter received clemency in 2022 and has been released.) “What distinguishes people from other animals is our capacity to transform and atone. We transgress, we’re held accountable, we transform, and then we make amends. Death by incarceration strips people of this experience.”

Huber agrees. “Everybody should have a chance to show their accomplishments [and how they’ve changed],” she said in a phone interview with The Nation. “I could have laid here and watched TV for the past 30 years, but I went and got certification, skills, things that I’d never get a chance to use. I just want a chance to prove myself.”

There is no time frame for the United Nations to decide whether to investigate the complaint. Should the body’s human rights experts decide to do so, they will begin by asking the US government for a response to the complaint with a deadline that can range from several to 60 days.

Pennsylvanians’ efforts to repeal felony murder and other extreme sentences have been less successful.

In 2018, lawmakers introduced a bill to extend parole eligibility after 15 years for those sentenced to life. A growing number of advocates with the Coalition to End Death by Incarceration converged on the state capitol at Harrisburg each year, culminating with nearly 500 in 2019. (The pandemic paused in-person protests for the next two years.)

In February 2021, lawmakers introduced SB 135, which would change sentencing for murder from life without parole to a maximum of 35 years to life. It has languished in the judiciary.

While legislation has failed to pass, these efforts have raised awareness among a growing number of lawmakers who are questioning these draconian policies. Democratic gubernatorial candidate Joshua Shapiro, who defended the state’s felony murder law as attorney general, has pledged to reform the law if elected this fall.

In 2020, Rose Dinkins’s only chance at relief—short of legislative change—was dashed when the state’s pardon board denied her application for clemency, or shortening her sentence.

“I implore the members of the United Nations to imagine becoming a shadow of a memory while still alive,” Dinkins wrote in her hand-written letter. “I have been missing from family celebrations for over 50 years.”

During her 50 years in prison, she enrolled in the prison’s educational, vocational, and self-help programs, earning her GED, associates and bachelors degrees, and cosmetology license. She also became certified as a paralegal and in auto mechanics.

“I have had time to reflect on my decisions and the circumstances that led to my incarceration,” the great-grandmother reflected. “I’ve learned a great deal about myself and grown tremendously. I believe laws should be passed to abolish DBI sentences because it implies people are not capable of change. These sentences provide no relief for reformed individuals.”