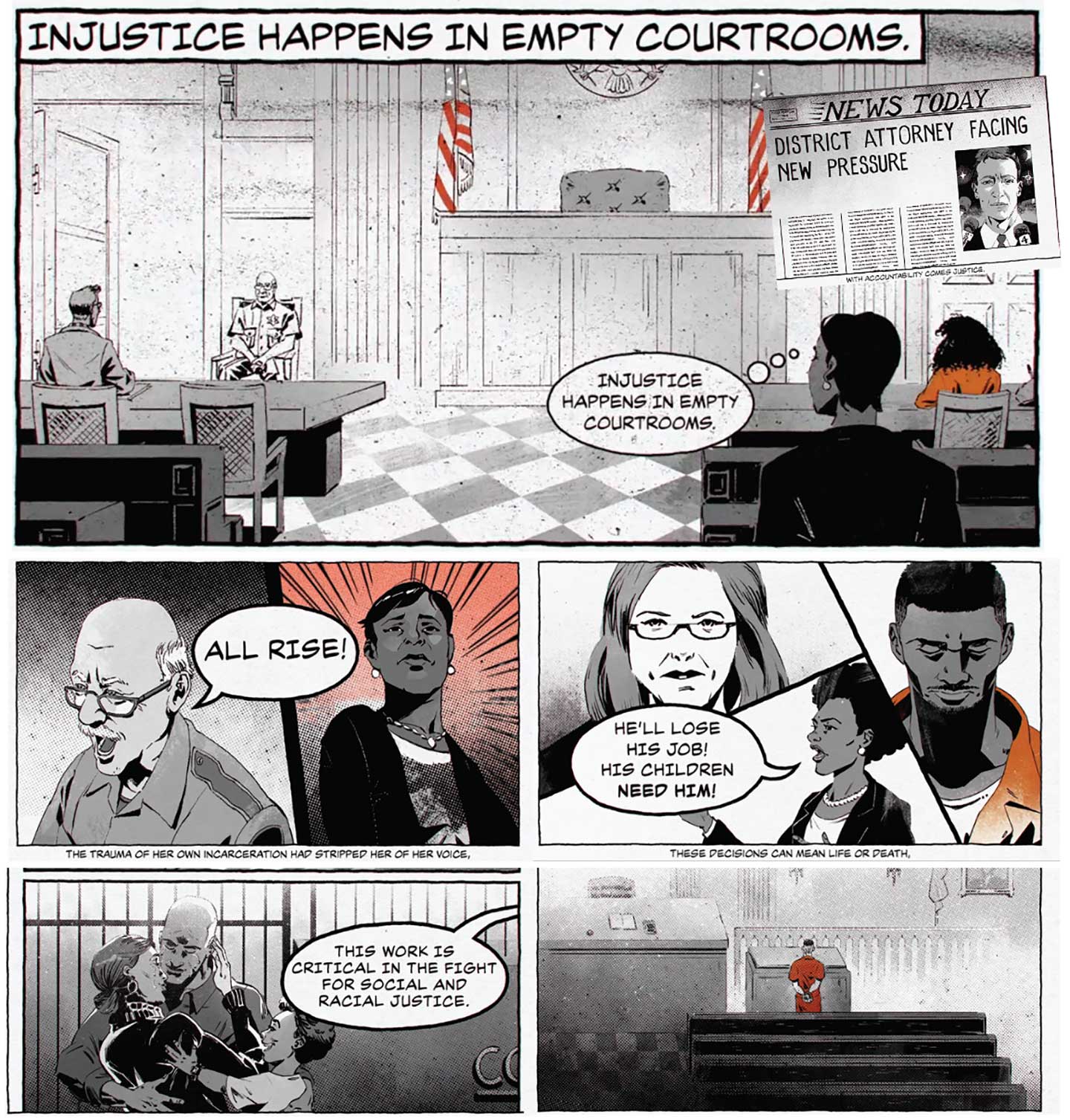

“We’re Only Here to Watch”

How courtwatchers are shifting the power dynamics in criminal courtrooms.

All over the United States, criminal courtrooms are full of poor people, disproportionately people of color, sitting on rows of benches—or, if there isn’t enough room, standing in hallways—waiting for their criminal cases or the cases of their loved ones to be called. When I was a public defender working in the Bronx, I once heard a young Black boy ask his father as they walked into a crowded felony courtroom, “Daddy, are we in church?” My heart sank at the boy’s question, as the superficial solemnity of a courtroom filled with people who looked like him met the tedium of the exchanges that the boy would find himself surrounded by once he sat down.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

For the words coming from the judges, clerks, and lawyers were not sermons; nor were they even the hearings and trials that many have come to expect from the media’s accounts of criminal court. In a New York City criminal courtroom, you might hear: “The People offer a 240.20 and community service.” “We have three bodies coming up.” “Do you waive the rights and charges?” “The People consent to an ACD.” “Case adjourned for motion schedule, time is excludable.” “Case adjourned for discovery.” “Case adjourned until the 180.80 date.” “The People are ready.” “Plea accepted. Mandatory court costs due in 60 days.” In the world of plea bargaining, in which well over 95 percent of cases do not go to trial, such statements make up the entirety of “criminal justice.” There is nothing more.

Between these statements, there is only waiting. So much waiting, even on a day with nearly 100 cases on the calendar: waiting for the judge to take the bench, for the prosecutors to find the right files, for the defense lawyer and defendant to appear—waiting that is then punctured by a blur of legal language. When I practiced as a public defender, between 2007 and 2012, the rules of Bronx Criminal Court forbade audience members who were not attorneys from reading in the courtroom. If a teenager was reading a book for school, a court officer would yell at him or her to put the book away and face forward in order to show respect—to listen to the words in the courtroom, as if those words carried important meaning.

The violence of criminal court is easy to miss in the faces of people appearing remotely on screens, the wrists in handcuffs, or the clerks handing out pieces of paper listing the fine amounts that people must pay to avoid being caged. The legal scholar Robert Cover, in a 1986 essay titled “Violence and the Word,” wrote: “I do not wish us to pretend that we talk our prisoners into jail. The ‘interpretations’ or ‘conversations’ that are the preconditions for violent incarceration are themselves implements of violence.” For those who work inside courtrooms, getting through a long day requires ignoring the violence of the courtroom and its language. It is in these courtrooms that assistant district attorneys refer to themselves as “the People” with casual certainty. And it is here where court officers, judges, clerks, interpreters, stenographers, program representatives, and even defense lawyers rush through their days with an eye toward leaving as soon as possible—or, worse, joke around with each other to pass the time while people wait handcuffed in dirty cells on the other side of the courtroom walls.

Enter the courtwatchers. When people enter courtrooms as a visible collective, not to wait for one case but to watch all of them, they disrupt the routine of casual forced submission. They wear matching T-shirts and take up entire rows. They come with pads and pens and fill out forms to capture the details of what they observe. The disruption is apparent immediately. It may be a court officer coming up to question their presence. It may be the prosecutors or defense attorneys whispering to each other and looking back. Or it may be a clerk telling them bluntly that they cannot come in if they are not connected to an individual case. So accustomed are court officials to seeing only the defendant’s family or friends in the audience that they often believe it is against the rules for strangers to watch courtroom proceedings, let alone groups of strangers. (They are wrong: The First Amendment generally protects people’s right to access criminal trials, whether they are family or not.) To simply be present inside a criminal courtroom as a collective—even when sitting quietly and following the rules, for most courtrooms do allow note-taking—is to push back against the established power dynamics there.

The criminal system’s actors are used to having an audience, but they are not used to being watched. It is hard to quantify the effects of the courtwatchers’ observation on the system they watch, but organizers with Philadelphia Bail Watch have given us a few data points. Their project emerged in 2018 as a joint effort of the Philadelphia Bail Fund and Pennsylvanians for Modern Courts. Philadelphia Bail Watch documents what goes on in the bail hearing room at the Philadelphia Criminal Justice Center, the city’s criminal courthouse. The basement room contains rows of seats for spectators, with a glass wall separating the audience from the hearing itself. Like the bulletproof glass of a liquor store, the glass partition situates the audience members as potential threats to the safety of the hearings—even though the people accused of crimes are themselves not even present, but rather streamed in by video. Philadelphia Bail Watch observes these hearings on and off throughout each year. Organizer Fred Ginyard explained that between one and 30 courtwatchers sit in the audience, taking notes on what the magistrates and lawyers say and decide.

Working with the bail fund, these courtwatchers also follow up with the people they see on the screens, whose bail is set by the magistrates in the room. One person freed by the bail fund described their experience on the other side of the screen in jail: “I heard all the questions they asked me, but I couldn’t hear when they were talking to each other. It was kind of hard to hear…and I was tired and dehydrated.” Using their own observations and the reflections of the people whose fates are on the line at the bail hearings, the watchers write formal reports and bring those reports to meetings with the courtroom players: the district attorney, the chief judge, the public defenders.

Once a year, these Philadelphia organizers conduct a 24-hour courtwatching effort, usually close to the holidays in December. Being there for 24 hours allows them to compare the outcomes of the day’s bail hearings with those from the rest of the year. In 2021, Ginyard headquartered the 24-hour effort in a hotel room across the street from the courthouse, so the courtwatchers would have a place to rest and snack between bail hearings. At least two watchers attended every hearing, in three-to-four-hour shifts from 8 am until 8 am the following morning. They wore matching black T-shirts with a royal blue outline of the Liberty Bell and “Philadelphia Bail Fund” in orange letters on the front. As the hearings continued into the night, there was evidence that the magistrates—five different ones over the course of the 24-hour period—noticed the courtwatchers, according to Ginyard. Two of the magistrates asked who they were through a microphone that broadcasts to the other side of the glass partition. Each time, the watchers replied, “We’re just here to observe.”

At one point, Ginyard witnessed the most comprehensive bail hearing he had ever seen: It took a full five minutes as the prosecutor and the public defender debated whether cash bail should be set, naming specific things about the accused person who appeared on the video screen, discussing his “ties to the community” and the importance of his criminal history. Ginyard gave a knowing look to his fellow watchers, who nodded back, amazed at what they saw as a performance for their benefit—the only time any of them had seen a bail hearing last for more than a minute or heard any of those arguments being made. As Ginyard said, “They put on a whole show…. It was like an episode of Law and Order.”

For the years 2018 and 2021, the courtwatchers have been able to draw quantitative conclusions about the effects of their presence, scraping data from the First Judicial District’s online portal and reconstructing the outcomes of bail decisions for every day of the year. (They were not able to get this data during other years.) In both years, the watchers found that during the 24-hour action, magistrates set cash bail less frequently than they did on other days of the year. This meant that magistrates were more likely to release people with no requirement that they pay money first, known as a release “on their own recognizance.” In 2018, for example, of the 97 people arraigned over the 24-hour period, 28 (or 28.9 percent) had cash bail assigned. According to a volunteer data analyst, this was the third-lowest “cash bail rate” for a 24-hour period in nearly a year. In 2021, the results were even more pronounced: During the 24-hour courtwatch organized by Ginyard—the one that included what the watchers saw as an extended performance for their benefit—magistrates set cash bail in just 25 percent of the cases. That 25 percent was not only lower than it had been on every other day of the year, but it was half the average rate of 50.1 percent.

The 24-hour courtwatches in Philadelphia provide a rare quantitative account of something that all courtwatchers report feeling as they sit in the audience: that they are changing the proceedings just by being there. In social science, this is known as the observer effect or, relatedly, the Hawthorne effect: People change their behavior when they know they’re being watched. Social theorists like Michel Foucault have examined how the act of watching can be a form of wielding power: In prisons, in schools, in hospitals, the architecture of observation by those in charge becomes a way to dominate and control people through surveillance. Social theorists call the turning of surveillance on those in power—watching the watchers—“sousveillance,” or surveillance from below. Sousveillance is a way to challenge the monopoly of those in power over information, technology, and control. And courtwatchers model how sousveillance becomes even more powerful when done collectively at the very location of domination, such as a courtroom.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Courtwatchers aren’t able to document all the details of how the system is operating. Though courtrooms are technically open to the public, they actively obscure what is happening within them. After sitting in her local municipal court, one volunteer for CourtWatch LA in Los Angeles wrote on her reflection form: “Imagine watching a foreign language art film. It’s all a blur. I maybe can capture a story, but not the specifics of the case. Or, if I get the specifics, [like the] case number, the story is obscured with jargon and information you can’t process.”

It is not just the legal jargon. Most of the “justice” has happened elsewhere: A police officer has decided to stop and arrest someone, a prosecutor has decided to charge them in the name of “the People,” and a defense attorney has reviewed the case and, sometimes, talked to their client. Legislators have in the first instance created the laws that allow these decisions. Countless other employees have done their jobs: They have handcuffed, caged, and fed human beings; typed, written, and stamped court forms; cleaned the courtroom; printed rap sheets and docket numbers; conducted assessments of people’s criminal histories, their employment status, their “ability to pay.” All of this has been done out of sight of the public. But to call attention to this smokescreen is to reduce its power; to bear witness to the little that is said in each case adds up to something larger. In this way, one basic goal of organized courtwatching is to create the palpable power shifts that can flow from the collective observation of those in power.

Courtwatchers also try to demonstrate solidarity with the people standing before the judges in handcuffs or appearing on video screens. Most fundamentally, the observers make the silent argument that those accused of crimes are people, too. Ginyard told me that part of the purpose of being a courtwatcher in Philadelphia’s bail hearing room is “to ensure that the person on the other side of that screen—who gets told ‘Don’t talk’ and ‘You can’t ask questions,’ and who gets ignored—knows that there are folks there to show that you can’t ignore a human being that you’ve put on a screen to dehumanize. You can’t ignore that, and we’re going to let you know.”

There are dangers in romanticizing observation. Knowing that people are paying attention to your case may be uncomfortable for some people accused of crimes, even if it is done in solidarity. And courtwatching faces more intrinsic limitations. Communal observation on its own cannot cure unfairness, even if it changes the behavior of state actors slightly in the moment. Bearing witness to someone’s being ordered into a cage does not make that outcome a fair one—and it can be a traumatic experience to witness the violence. Over time, officials may adjust to being watched, and transparency can legitimate and obscure what might otherwise be seen as oppressive.

On its face, the performance that the Philadelphia courtwatchers observed when the attorneys and magistrate seemed to carefully consider and argue a case before them might represent an ideal example of public justice. And yet, when the person went to jail after the magistrate set bail, the result did not become “justice”—or at least not the courtwatchers’ idea of justice—simply because the legal language of incarceration became momentarily comprehensible. Instead, the performance highlighted for the courtwatchers the absurdity of a system in which state actors can, on command, recite with feeling the arguments, reinforced over decades, necessary to justify incarceration.

At its most subversive, observation can cut through the obfuscation that legal language produces, undermining the legitimacy of the system that the language upholds. The benefit here does not come simply because, in the oft-quoted words of Justice Louis Brandeis, “sunlight is…the best disinfectant,” but rather because the people opening the windows are the people traditionally shut out of the process of “justice.” In those moments, “the People” are no longer just the assistant district attorneys; they are also the average people in the courtroom—people who do not approve of what the ADAs are doing in their name. As the Rev. Alexis Anderson, a founder of Court Watch Baton Rouge in 2019, says of the courthouse in which its members do their watching: “When we enter, we consider it the People’s House!”