Brazil Is Soccer’s Holy Land—Unless You’re a Woman

The women’s national team has never won a World Cup—thanks in part to a decades-long legacy of sexist exclusion from the game that’s only starting to wane now.

Members of Brazil’s women’s national team after being knocked out of the 2023 tournament in Melbourne, Australia, on August 2, 2023.

(Hamish Blair / AP)It’s no surprise that most of the countries currently competing in the Women’s World Cup in Australia and New Zealand have never won the tournament. The sports world is as unequal as any other, and a lot of players are probably just happy to have made it to the competition at all.

But here’s something that is surprising: One of those teams with zero wins is Brazil.

Yes, that Brazil. Despite being perhaps the most dominant force in soccer history, Brazil has never fielded a winning team for the Women’s World Cup. It made the finals once, in 2007, and found repeated success in Latin American-wide tournaments, but it has yet to claim a trophy on the world stage. That unhappy streak continued on Wednesday morning when Brazil was knocked out of the 2023 tournament after a 0-0 tie with Jamaica.

Meanwhile, the US and European teams have triumphed repeatedly. As Jack Lang wrote for The Athletic, “It’s one of those facts that seems like it can’t possibly be true but is.”

Lang calls the Brazilian women’s relative lack of success “a strange quirk of history,” what with Brazil’s men having five wins and the women having had all-stars like Marta, Cristiane, and Formiga. In one sense, he’s right—it does seem inherently odd that the women’s team hasn’t won. But if you look a little deeper, you’ll find that rather than some inexplicable twist of fate, that missing win is the result of deliberate, damaging policy choices as much as devastating penalties and 0-0 ties. In soccer’s holy land, repressive politics, sexism, and lack of funding for women’s soccer reigned supreme for decades—and that’s only now beginning to change.

One reason the men’s team has such a lopsided win count is that they had the field to themselves for decades. In 1941, Brazil banned women altogether from playing soccer, at any level. (It was not alone in making this ludicrous choice.) By 1979, the year the ban was lifted, the men’s team had won the World Cup three times. It would be another 12 years before the Women’s World Cup even began.

When it did, Brazil’s lack of interest in its women’s team was clear just by looking at them: The women played in boxy, men’s cut, three-starred jerseys—literal hand-me-downs. What’s more, outside of global competitions like the World Cup, Brazil had no consistent professional women’s league (a stable nationwide league didn’t exist until 2013). At the youth level, investment in girls’ athletics was an afterthought.

Marta, now widely considered to be the greatest female soccer player of all time, couldn’t find a girls’ team when she first started to play in the 1990s. She’d dribble alone in the street, with grocery bags wadded up in the shape of a ball. Eventually, she practiced with boys—but in a culture where her skill, at times, paradoxically undermined her: She played so well that she was kept from competing in some boys’ tournaments. If she scored on a male goalie or knocked out a defender, that would be bad for the boys’ morale–embarrassing, coaches seemed to reason. Better to sit her out.

Even so, it was clear that she had real talent. As a teenager, she moved to Rio de Janeiro, where she played for a new women’s side at Vasco da Gama, and then to Recife, to play with Santa Cruz. But that double-blow of nonexistent girl’s teams and exclusion from boy’s squads remained common in Brazil—well into the early 2000s.

I experienced this myself. When I tried, at 10 or 11, to play with a boys’ club for the summer in my aunt’s neighborhood of Belo Horizonte, coaches turned me away, without even letting me try out, for the same reason. The irony of their assumption that a girl could be too good was lost on them, and when I returned to the United States, my failure became irrelevant. I was no Marta, but I had the option not only of a girls’ team but a girls’ travel team—and then later, a national premier league (NPL) team, and a high school team. When Márcia Taffarel, who played midfield for Brazil’s first World Cup squad, came to the United States, she saw a “paradise of women’s soccer.”

In the US—where the women’s team has won half of all World Cups to date—the legacy of policies like Title IX has made it so that nearly 400,000 girls play for their high school soccer teams. The women’s national team is also light years ahead of its male counterpart in international competitions. In Brazil, o país do futebol, soccer doesn’t even make a list of the four sports most practiced by teenage girls. (It is—dare I say, obviously—the top sport for boys.) In terms of athletics more broadly, girls’ participation in sports lags behind boys’. Those who go on to play professionally, for the most part, leave the country. Two-thirds of Brazil’s current national team plays abroad professionally, with eight in the NWSL.

After Brazil was eliminated by France in the round of 16 at the last Women’s World Cup, Marta made a plea to the young girls watching: “There isn’t going to be a Formiga forever. There isn’t going to be a Marta forever. There won’t be a Cristiane. Women’s soccer depends on you to survive.” Beneath her impassioned speech was a familiar subtext: The government, most men, those in power—they don’t care about you, or women’s soccer, or even women at all. To be a girl in Brazil is to fight for your right to play, and to be a woman on the national team is to carry the burden of legacy.

The year after the 2019 Women’s World Cup, and after years of advocacy, the Brazilian Football Confederation (CBF) announced that the women’s national team would receive the same allowances and minor tournament prizes as the men. Then-President Jair Bolsonaro, so obsessed with the men’s side that he co-opted the yellow jersey as the symbol of his far-right politics, later mocked the equal pay decision. “There are ridiculous notions…comparing women and men playing soccer, asking why Marta earns less than Neymar,” he said. “There is no comparison. Women’s soccer is still not a reality in Brazil.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The quip was unsurprising—to minimize women athletes’ decades of grit and success in an environment rigged against them was in lockstep with Bolsonaro’s governance. And to worship the men while diminishing the women was a page right out of the playbook of the brutal dictatorship Bolsonaro repeatedly, publicly, said he admired. In 1970, when Pelé brought home the men’s third trophy, Brazil was in the Years of Lead of that dictatorship—one that exploited soccer success to bolster its public image, finding it easier to market the military men coaching the national team than the many more who were torturers and murderers. It was during this dictatorship, too, that the ban on women’s soccer was made even more explicit. “Women,” began the decree, “are not permitted to practice sports incompatible with their nature.” To do so would be to undermine the reproductive labor by which they had been defined.

In response to Bolsonaro, Marta wrote just a sentence: “Some will be remembered as the greatest of all time, while others…” She left us to fill in the blank.

Things are headed in the right direction, though. This month, Marta, a rainha do futebol, a melhor do mundo, played in her last Cup. But she also recognized this year’s tournament was the “greatest Women’s World Cup” yet in terms of public support, and, at a press conference on Wednesday, vowed that this was just “the beginning” for the women’s game in the country. Part of that feeling, for Brazil at least, is the historic firsts that she, Formiga, Cristiane, Márcia Taffarel, and all the women of previous generations paved the way for.

This year, the CBF announced plans to introduce 64 women’s clubs as counterparts to existing men’s teams by 2027. On July 14, President Lula’s government declared that for the first time, public officials would be granted time off during the women’s team’s Cup matches. The policy, known as ponto facultativo, has existed for men’s matches for over a century—and in a country where life stops to watch Neymar play, that small step towards parity is a big deal.

A few days later, the CBF confirmed that, for the first time, Brazil’s women would play a World Cup without the men’s stars on their chests. When, at the request of players, the new uniform was released and worn, it was described as an affirmation of independence. And after Brazil was knocked out on Wednesday, Lula stressed the importance of “investing more in women’s soccer.”

Those are World Cup wins—in that they’ll each shape the developing future of Brazil’s women’s soccer. And when, one day, they win for real, it will be because of a history they’ve created. As Brazilian player Andressa said, “We will win our star. And when we do, we’ll carry it with us.”

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

The US Is Looking More Like Putin’s Russia Every Day The US Is Looking More Like Putin’s Russia Every Day

We may already be on a superhighway to the sort of class- and race-stratified autocracy that it took Russia so many years to become after the Soviet Union collapsed.

Israel Wants to Destroy My Family's Way of Life. We'll Never Give In. Israel Wants to Destroy My Family's Way of Life. We'll Never Give In.

My family's olive trees have stood in Gaza for decades. Despite genocide, drought, pollution, toxic mines, uprooting, bulldozing, and burning, they're still here—and so are we.

Trump’s National Security Strategy and the Big Con Trump’s National Security Strategy and the Big Con

Sense, nonsense, and lunacy.

Does Russian Feminism Have a Future? Does Russian Feminism Have a Future?

A Russian feminist reflects on Julia Ioffe’s history of modern Russia.

Ukraine’s War on Its Unions Ukraine’s War on Its Unions

Since the start of the war, the Ukrainian government has been cracking down harder on unions and workers’ rights. But slowly, the public mood is shifting.

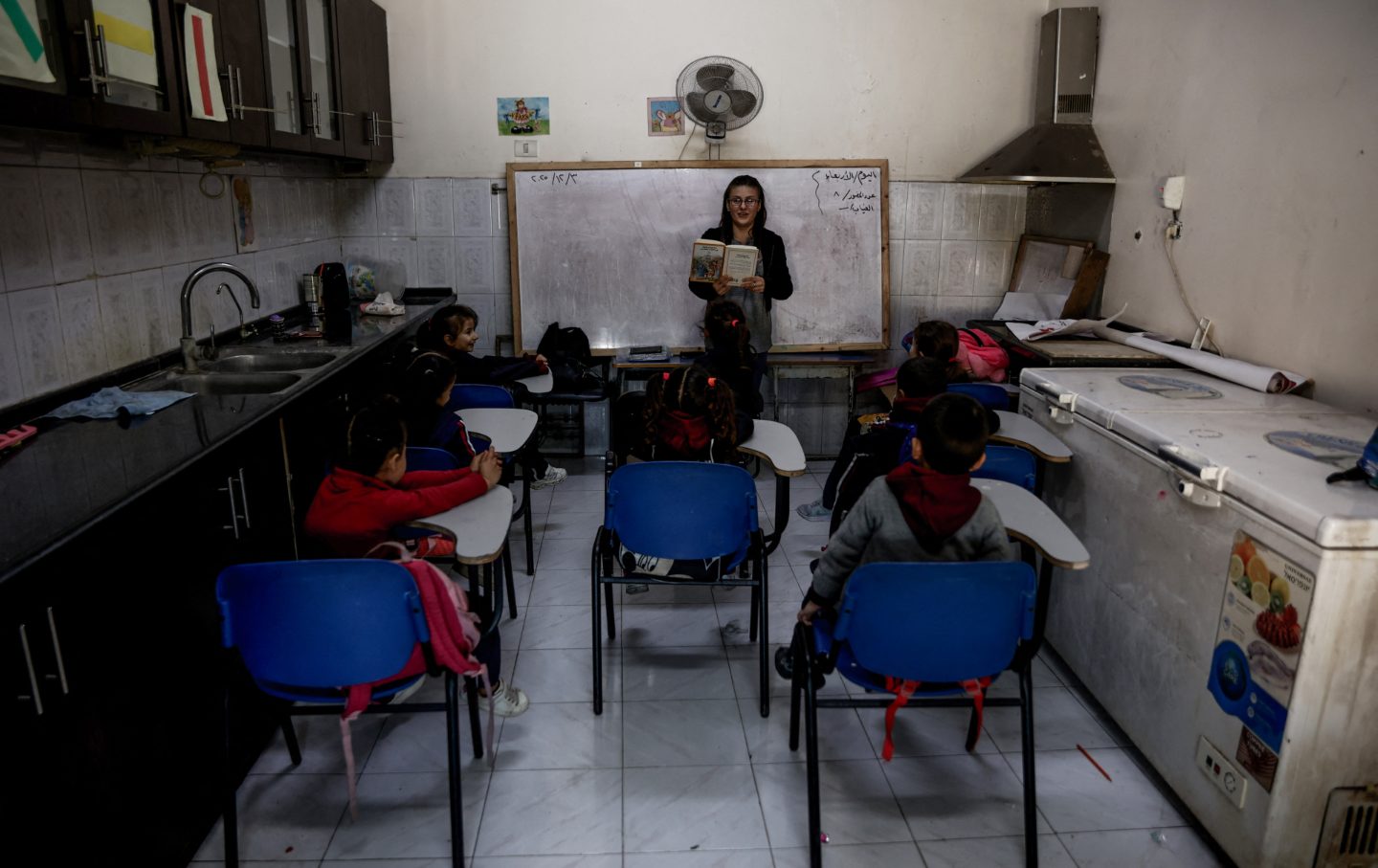

I’m a Teacher in Gaza. My Students Are Barely Hanging On. I’m a Teacher in Gaza. My Students Are Barely Hanging On.

Between grief, trauma, and years spent away from school, the children I teach are facing enormous challenges.