The Show Must Go On: Behind the Scenes at a Tennessee Drag Show

Meet the performers serving queer education in a deep-red state.

Off the Clock is a monthly column that brings us into the after-hours lives of people on the left.

Knoxville, Tenn.— Queen Anastasia Alexander has a logistics problem. In two hours, she has to drive to Chattanooga, and she needs that time to get ready—even after 16 years, becoming Anastasia is a lengthy process. There’s just one challenge: In Knoxville, Tenn.—home to the Krystal burger, the company that gave us the Dumpster, and the first drag ban of 2023—Anastasia does not get out of the car as Anastasia. And she needs gas.

I am the problem here. I was running late, and she needed to fill her tank before she would head out. This left me waiting outside the queen’s house, at the end of a gravel driveway off the highway, for her to return.

Anastasia, better known as John, is a 35-year-old drag queen who does customer service by day and back handsprings at Club XYZ in Knoxville by night. Amid an anti-trans and anti-queer legislative nightmare, John is on a mission: to acquaint straight people with drag. This evening, he and a handful of other drag performers from East Tennessee will perform a family-friendly drag show in Chattanooga for an audience that includes religious leaders and influential community members. A local nonprofit has gathered the performers as part of a larger effort to foster respectful dialogue on sensitive topics.

Though casual, it feels consequential. As lawmakers continue their relentless legal battle against trans and queer rights, the queer people I know are suspended in a solution of equal parts fear, distraction, uncertainty, and a desire to not panic, lest they alienate moderate allies pumped with misinformation.

A blue Hyundai growls down the gravel. Out pops a roughly 6-foot-tall angel with a flat top, a brown glow, and a wide smile. “Hey, girl,” John says, ushering me into the house.

Time to glam.

It’s 4:12 pm in John’s sanctuary: that is, the room in his and his husband’s home that he devotes to all things Anastasia. To the left of the door, 29 pairs of heels rest on a shoe rack. On the desk: a standup mirror and a lazy Susan filled with lipstick and makeup brushes. Above it all, three of the cabinet shelves are devoted to brightly colored hair spray bottles assembled in neat rows.

“I very much see Anastasia as an extension of myself, but not who I am,” John says. Well-meaning cis people often confuse the character for a trans-feminine gender identity. It’s this kind of nuance that is often lost in the bluster of a moral panic. “We all have certain things we want to portray and do out, and drag is just an extension of that concept. Nobody gives it a second glance when it’s an actor.”

But when John wears a wig and slinks across the stage as Anastasia on public property and in front of anyone under the age of 18? That, according to Tennessee’s legislative and executive branches as of April 1, is an adult cabaret performance harmful to minors and punishable by a Class A misdemeanor or Class E felony.

What this means for the future of the state frightens John. The uncertainty and threat of violence remind him of the increase in hate crimes that Donald Trump’s election in 2016 emboldened. Like many drag performers of color, questions have begun to overwhelm his thoughts: Will my queer club be shot up next? How will I respond? When the club announces my name before a performance, will it allow someone to target me?

Helpfully, a federal judge in the Western District of Tennessee temporarily halted the rollout of Tennessee’s drag ban in early April, citing the sweeping potential of the law to criminalize protected speech due to its vague language. In the meantime, the right-wing push to demonize queer existence in legislative and judicial systems has spawned drag-ban bills in at least 13 other states.

For much of his life John absorbed this kind of discrimination. The oldest of his mother’s two children, John grew up in rural North Carolina with his Southern Baptist grandmother, so sheltered and alienated from frequent moves that he was unsure of his sexuality until he was 18. Not knowing he was queer, when others seemed to know, was confounding, John says. “Like being tested on something, but you don’t know the answers or the questions.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →But it also spawned a wellspring of empathy. “My grandmother did the best she could,” John says. “She was raised Southern Baptist, so I was raised Southern Baptist. I can honestly say she never stopped loving me. She was just in fear of what her heart and her mind and her brain were telling her—and then what the Bible was saying, and what the preachers were saying, and what her friends…were telling her at the same time. That’s a lot of different chefs in the kitchen, you know what I’m saying?”

As a teenager, John was lonely and often retreated to the world of television: a magical place where it was easy to decode a character’s confusion, played for laughs. Where you could be imaginative without getting called a “faggot.” Where you didn’t have to worry about when to punch your bullies versus when to spit at them.

When he turned 18, John went to his first drag show—though at the time, he didn’t know it was drag. “Why does the MC keep calling [these women] drag queens?” he remembers saying to the friend who brought him. A drag queen is a guy who dresses up in girl clothes, his friend replied. That’s what he was looking at. “I flipped out,” John says. “No, no, nope. This is not covered by the Bible. I cannot be here.”

The shame is funny now—but it’s why John is compassionate with the ignorant and tender with the baby queers. He, too, once feared what he did not know.

John tells this story while sculpting his face with brushes and sticks. He swirls on the foundation. Then he draws two contouring lines that streak from each side of his nose to each side of his temple. After darkening the outer streak edges as needed, John dots the corners of his eyes with a golden glitter. My favorite moment is when he carefully applies a rosy eyeshadow to one half of his eyelid at a time. Over time, the layers of precision meld into an optical illusion that draws one’s eyes toward perfectly chiseled cheekbones.

At 5:15 pm, face complete, John smooths a piece of tape over his nose to prevent his glasses from smearing his makeup.

Almost showtime.

The roadtrip to Chattanooga is what you might expect from a gay man and a trans woman in the Southeast. We joke about which boys could ruin our lives. We pass a “TRUMP MAGA” message written on a roadside trailer. I learn that John crushes on Anderson Cooper so hard that no one is allowed to even think about the silver-haired CNN news host.

By 7:38 pm, we’re lugging John’s suitcase through the unassuming doors of the Seed Theatre, where roughly 30 religious leaders and community members have assembled in front of a raised stage.

I open the door backstage. Instantly, a wall of hair spray burns my nostrils with the smell of alcohol. I can barely move without stepping on someone’s suitcase of clothes. In one corner, a queen dressed in only spandex affixes a bald cap. Opposite her is a nonbinary beauty working on their eyeshadow. Anastasia slides into five pairs of spandex. Because all three mirrors are in use, she waits her turn to complete her eyelashes.

While prepping for the show, the performers—Gemini, Hormona, Therapy, Rita, and Anastasia—engage in the kind of exchanges that you can only witness when several kinds of queer and trans people assemble. They talk about neurodivergence and whether a “family friendly” song can include the word “shit.” Anastasia sings opening tunes from her favorite television shows and challenges Gemini to guess them. At one point, the MC, a trans woman, spies a cute audience member and informs the room. Therapy teases everyone by saying one of the categories should be “Family Dollar Items Only.” “Why’s she coming after us?” Anastasia howls from across the room.

It’s a small circuit. The performers either know each other or know of each other from social media and shows. Anastasia is acclaimed among them for her acrobatics: She leaps, cartwheels, does back handsprings. It’s something John picked up from the drag scene in Asheville, N.C., where he debuted 16 years ago to a Tina Turner mixtape.

At 9:38 pm, the changing room bristles with pre-show jitters.

It’s showtime.

A drag show in the South usually has a few staples: an MC who vacillates between politesse and punchiness; at least one reference to Dolly Parton; and, depending on the scene, a lot of “body” and face makeup. Hormona meets two out of the three criteria when she opens the show, in a pink dress and crown, face caked in white makeup à la Marie Antoinette, to a cover of Parton’s “Jolene.”

There are a few differences from the shows I’m used to. The audience is all seated, and at first they are eerily quiet. But they catch on to the rhythm of applauding and tipping as the performers dart in and out of the spotlight. During her first performance, Therapy repeatedly squats to the floor in a pair of blue heels while using her hands to form “snapshots” around her face. This, as the MC explains, is voguing. Gemini, the nonbinary performer, takes an even-lesser known route when they walk onto the stage in a red-and-black suit with shoulder spikes. As I watch the crowd, I wonder if they had known that drag can be masculine, or genderless, and delightfully weird.

Backstage, Anastasia stands by the door, anxiously awaiting her turn as the last performer. After all this time, she still gets nervous. “Do I look OK?” she asks, gesturing to her flowing yellow dress that convceals a red top and a gold skirt. Yes, queen. When the MC calls her name, Anastasia bursts through the door and onto the stage.

Anastasia is patient at first, keeping her moves to a minimum as the audience settles into the first third of the dance mix. At the cue of an upbeat number, she peels off the costume’s first layer and jumps off the stage, touching her toes in mid air. After she lands, she drops onto her knees and dances from the floor. Then she pops back onto her feet—look, no hands!—and struts into the crowd, stopping only to squat in front of any particularly friendly tippers. As the disco beat starts to phase out, Anastasia dances her way to the front of the room, then springs backwards off of her hands, from the floor, back onto the stage—her fabled back handspring.

The audience erupts in applause—but the mix is not done. Nor is the queen.

Anastasia leaps from the stage again—this time with a front handspring—and a once-shy audience member hollers and holds up a dollar. As Anastasia grabs it from his hand, he smiles.

It’s 10:15 pm in Chattanooga, Tenn., and drag lives forever. Mission accomplished.

We cannot back down

We now confront a second Trump presidency.

There’s not a moment to lose. We must harness our fears, our grief, and yes, our anger, to resist the dangerous policies Donald Trump will unleash on our country. We rededicate ourselves to our role as journalists and writers of principle and conscience.

Today, we also steel ourselves for the fight ahead. It will demand a fearless spirit, an informed mind, wise analysis, and humane resistance. We face the enactment of Project 2025, a far-right supreme court, political authoritarianism, increasing inequality and record homelessness, a looming climate crisis, and conflicts abroad. The Nation will expose and propose, nurture investigative reporting, and stand together as a community to keep hope and possibility alive. The Nation’s work will continue—as it has in good and not-so-good times—to develop alternative ideas and visions, to deepen our mission of truth-telling and deep reporting, and to further solidarity in a nation divided.

Armed with a remarkable 160 years of bold, independent journalism, our mandate today remains the same as when abolitionists first founded The Nation—to uphold the principles of democracy and freedom, serve as a beacon through the darkest days of resistance, and to envision and struggle for a brighter future.

The day is dark, the forces arrayed are tenacious, but as the late Nation editorial board member Toni Morrison wrote “No! This is precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.”

I urge you to stand with The Nation and donate today.

Onwards,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

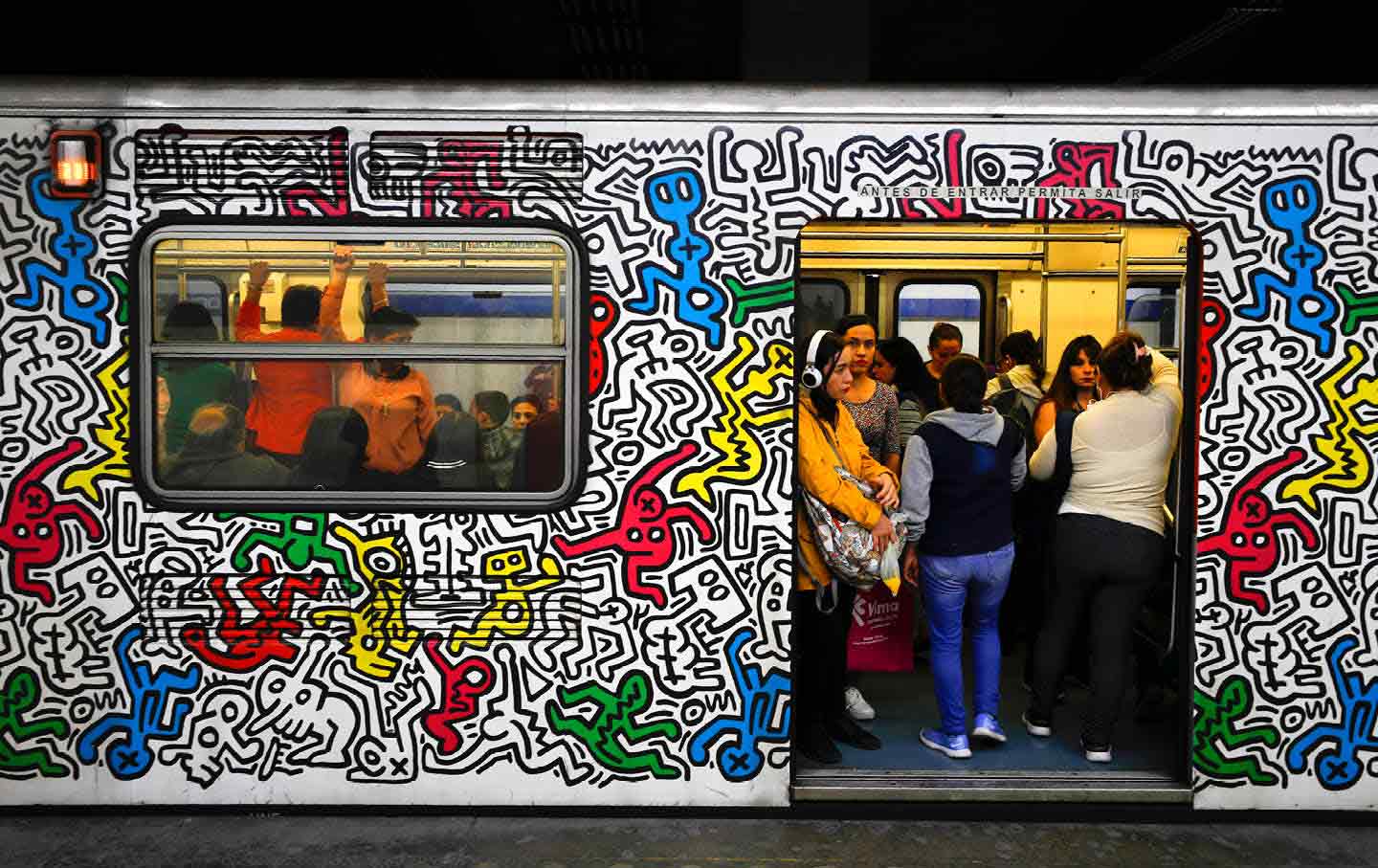

The Nonstop Gay Sex Party on the Mexico City Subway The Nonstop Gay Sex Party on the Mexico City Subway

The city’s metro hosts—and authorities unofficially sanction—a queer institution unlike any other.

Journalism’s Next Wave Journalism’s Next Wave

In 2024, writers with StudentNation captured the stories of an emerging generation—and revealed the future of journalism.

Who’s Watching the Kids Who’s Watching the Kids

Republicans are pushing a dangerous solution to the nation’s childcare crisis: deregulation.

Illinois Has Put an End to the Injustice of Cash Bail Illinois Has Put an End to the Injustice of Cash Bail

Amid a national backlash against criminal justice reform, Illinois has achieved something extraordinary. It’s working better than anyone expected.

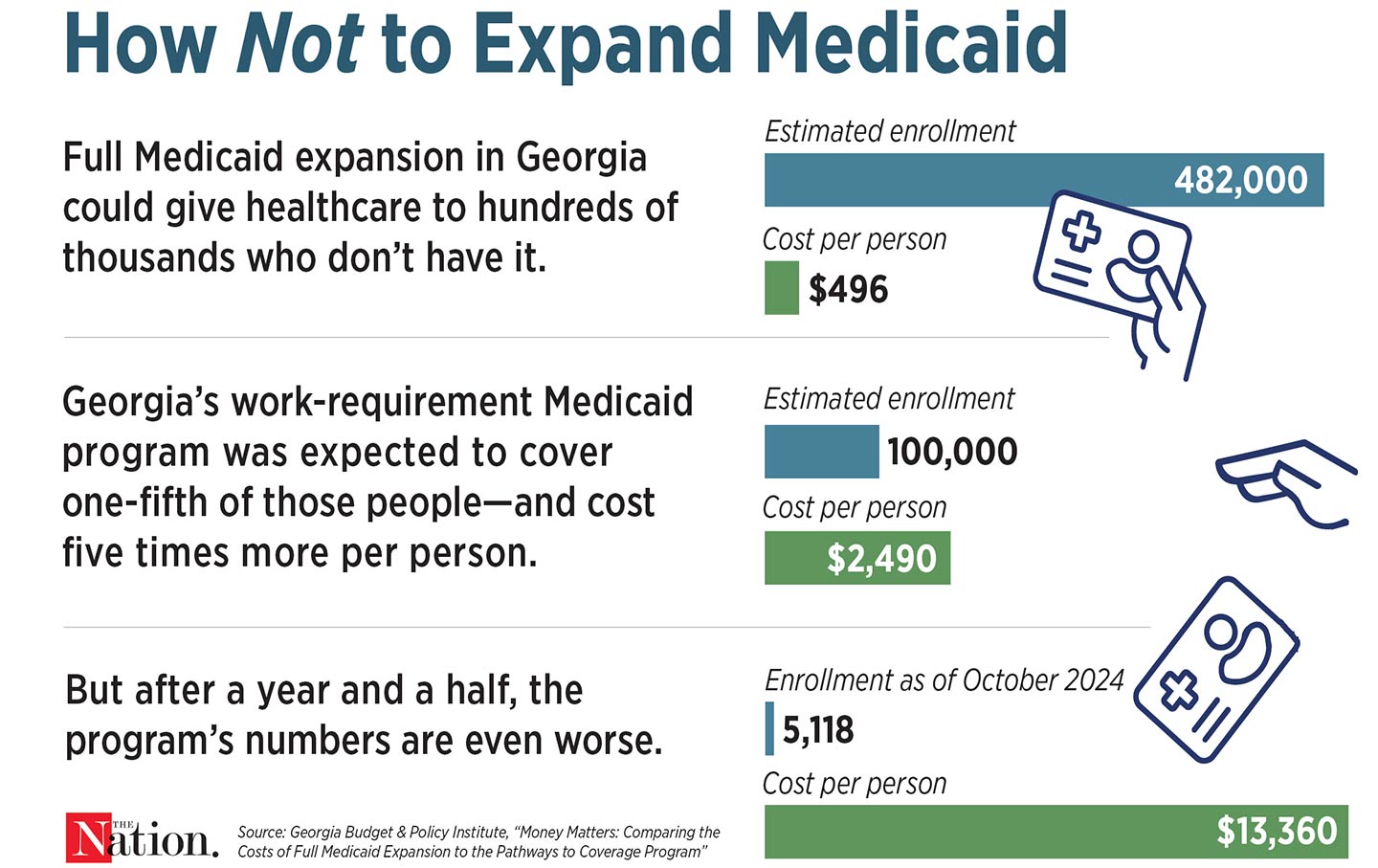

Georgia’s Disastrous Medicaid Work Requirements Georgia’s Disastrous Medicaid Work Requirements

Georgia’s Republican governor, Brian Kemp, said that 345,000 would enroll in the state’s Medicaid program, which has strict work requirements—so far just 5,118 people have.

Where Do We Go From Here? Where Do We Go From Here?

Thinkers, activists, and writers share their ideas on how to respond to the coming Trump era.