Dissolve Into Nothing

The enigmatic science fiction of Djuna.

The Enigmatic Science Fiction of Djuna

The radical visions of South Korea’s mononymous, pseudonymous, and officially anonymous sci-fi novelist and film critic.

It would be easy to list the conditions that make South Korea ideal for science fiction. There’s the next-gen Internet, the past-meets-future cityscapes, the ubiquity of plastic surgery. There’s the fact that a handful of megacorporations manufacture and run just about everything, and that the nation’s population is shrinking toward a vanishing point; the country currently has the lowest fertility rate in the world. There is also the fact that two decades ago, South Korean scientists became the first to clone a human embryo, and then cloned a pet Afghan hound. Perhaps most sci-fi of all is the militarized border and what lies across it: the counterfactual sister state of North Korea.

Books in review

Counterweight: A Novel

Buy this bookScience fiction has long flourished on the Korean peninsula, starting in the early 1900s with translations of H.G. Wells and Jules Verne. By the mid-20th century, Korean writers were producing works of their own, initially as didactic stories in science education magazines and as vehicles for veiled social criticism. From the 1960s through the ’90s, the conventions of sci-fi proved well suited to describing what Sunyoung Park, a literature professor and translator, calls “the malaise of living under dictatorship in a fast industrializing society.” In Cho Se-hui’s best-selling novel The Dwarf, from 1978, a poor and rather abject family displaced by urban renewal clings to fantasies of space travel. The daughter absconds to do sex work but is rumored to have been kidnapped by aliens. “I dreamed every night,” she says. “In the dream my brothers had found jobs at a different factory and had left for work. Father made several trips a day to the moon and back.”

In the 1990s, Korean science fiction blew up and matured into a distinct form, powered by the early Internet, zine culture, and networks of fan clubs. Only some of this literature has been translated into English, but the movies and TV it helped produce have enjoyed a global reach: Bong Joon-ho’s The Host (US military dumps mutant-making toxins into Seoul’s Han River); Jang Joon-hwan’s Save the Green Planet! (ordinary guy tries to save Earth from a nasty alien disguised as a pharma bro); and the Netflix series The School Nurse Files (white-coated protagonist battles invisible jelly-like monsters), based on Chung Se-rang’s novel School Nurse Ahn Eunyoung.

One of the most popular science fiction writers in South Korea is Djuna, a mononymous, pseudonymous, and officially anonymous novelist and film critic who emerged in the mid-1990s as an active poster on the chat server Hi-Tel. Online sleuths have their theories about the person behind the name: Djuna may have been born in the 1970s; may live in the city of Bucheon; may be Catholic; and may even be a three-person collective. What is certain, based on Djuna’s film criticism, is that Djuna loves Anna Paquin, Cate Blanchett, and movies with strong female leads—and likes to poke fun at the autoerotic repetitions in the movies of Hong Sang-soo. We also know that Djuna is quite prolific, having written thousands of online movie reviews and dozens of stories and novellas, mostly sci-fi but also mysteries. Between 2019 and 2021, Djuna was president of the Science Fiction Writers Union of the Republic of Korea, appearing in publicity photos as a cuddly brown bunny.

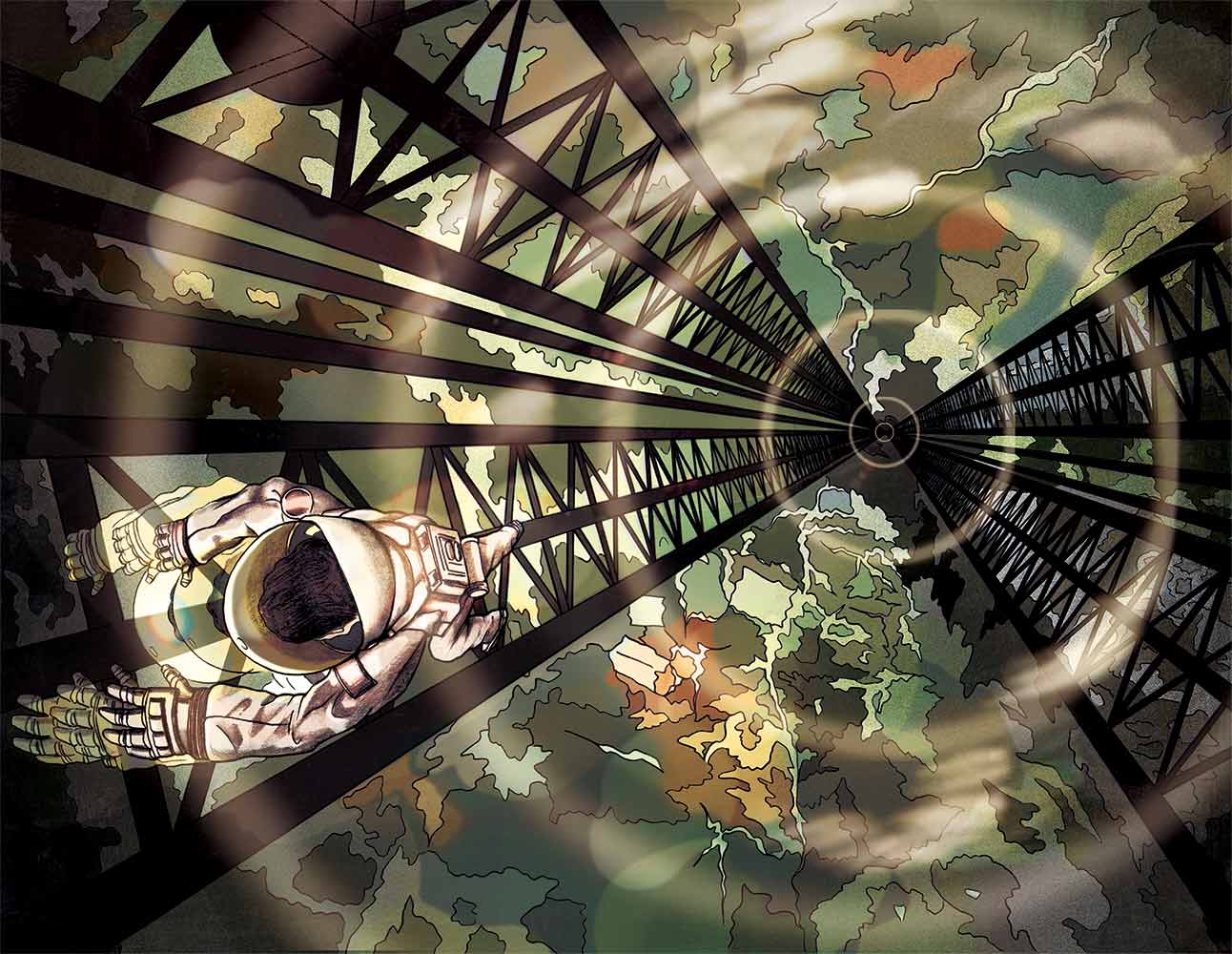

Over the past decade, a few of Djuna’s stories and interviews have made their way into English. Now Pantheon has published a novel, Counterweight, translated by Anton Hur, the essayist and translator of the South Korean writers Kyung-sook Shin and Bora Chung. Counterweight, which started out as an idea for a movie, originally appeared in South Korea in 2021. It tells the story of LK, a futuristic Korean chaebol that’s only slightly more evil than the conglomerates of today. LK colonizes a fictional Southeast Asian island called Patusan in order to build the world’s first elevator into space. (The “counterweight” of the title refers to its anchoring mass.) The elevator is the impressive realization of “a dream proposed by speculative fiction writers of old,” as Djuna writes, and so not all that original. But this one has a lurid backstory and a murder mystery that two LK employees try to solve. Though the book’s storylines can get twisty, they accrue into a sort of anti-colonial eco-noir set in a rapacious Korean corporation—which is to say, the global economy.

Like Djuna, Counterweight’s narrator, Mac, is an enigma: No one knows his real name, his nationality, or what his face looked like “before the surgery.” Mac’s history isn’t quite explained—he describes himself as “some old queen”—but he owes his new identity to Han Junghyuk, LK’s now-deceased president. As a functionary in LK’s external-affairs department, Mac serves the company loyally, monitoring laborers and killing off Patusan resistance fighters who, understandably, aren’t all that happy with their corporate/colonial overlords. Mac’s brain is plugged into LK’s Worm, a mega-database, which fools him into believing that he sees all and knows all.

But Mac comes to have doubts about this work—and the corporation that he works for. Could there be “a conspiracy that doesn’t involve me?” he wonders. One day, while engaging in routine surveillance, he decides to investigate a nondescript yet politically suspect office worker named Choi Gangwu. Mac later uses Choi in a counterinsurgent sting, only to witness the object of the sting get killed—but by whom? Was it a political assassination by the Patusan Liberation Front, or was it the fatal result of a transaction gone wrong with Green Fairy, a mercenary spies-for-hire group on the island? Or was the victim collateral damage in the succession battle among Han Junghyuk’s many descendants?

Partnering up with Choi, Mac tries to solve this mystery and discovers further crimes en route: the rape of two school girls (reminiscent of US military actions in South Korea), revenge killings involving handsaws, (even more) colonial land confiscation, a bomb attack. Mac’s hagiographic picture of the firm darkens, then splinters altogether. He realizes that Han Junghyuk has left behind an AI fragment of himself to guide the completion of the space elevator and override LK’s current leaders, including Han Junghyuk’s own son. “LK, to this day, is steered by the ambitions of a dead man,” Mac tells us.

Thoroughly disillusioned, Mac decides to switch sides and do all he can to destroy what remains of Han Junghyuk. Every clue points skyward, to the space elevator’s counterweight in deep space. To get to it, Mac and Choi Gwangu conspire against, and then with, an obscure relative of Han Junghyuk’s, a scientific genius whose two mothers (there are many queer characters in the book) were anti-capitalist, anti-colonial intellectuals. The two men use fake identities to stage a hostage situation, then launch an escape by space pod into the Indian Ocean. Mac and Choi’s operation is successful, for now. LK’s company AI is advancing fast, beyond the point of needing, or being susceptible to, “any kind of human intervention.”

Djuna assembles this fictional near-future from bits of the nonfictional present. Though superficially otherworldly, the villains who populate Counterweight feel familiar. LK could be Amazon or Tesla, Apple or Google—or, more to the point, one of many hereditary chaebols in South Korea: LG, SK, Samsung, Hyundai. The island of Patusan is make-believe, but South Korean companies do operate colonial factory towns throughout Southeast Asia, full of “thousands of people breathing, eating, excreting, sleeping, vomiting, copulating, and popping out babies,” Mac observes as his “insides turn.” The novel’s transnational corporations burn through workers and exploit both the deep sea and space for profit. The tropics are only the first to get plundered.

Counterweight is not primarily an environmental narrative, but the novel excels at descriptions of how capital swallows and spits up the natural world. We learn that Patusan had once been forested and thick with animal life; its “villages and cities…collapsed after draining their aquifers.” Most of the island’s inhabitants moved to Tamoé (also partly colonized by LK) and Pala in the same archipelago. Meanwhile, Patusan became full of insects, especially butterflies, which continued to flourish as the space elevator drew thousands of migrant workers to the island. Choi Gangwu’s first appearance in the book, in fact, is as an amateur lepidopterist: He is stuck in a muddy riverbank while taking “a photograph of an emerald butterfly sitting on a discarded Coke can.” Later, in another scene, Mac and Choi Gangwu go out for dinner, “down from the new city and into the ruins of the sunken city, where the Indigenous population lives,” and admire a bevy of “glow-in-the-dark aquatic insects.” Watching them under “the accompanying full moon,” moonshine in their bellies, Mac wonders if their view is “excessively beautiful, verging on tacky.”

Tackiness in Djuna’s fiction is not necessarily a bad thing. The author likes to play with gaudy excesses and clichés snatched from films. As a critic, Djuna has made a habit of cataloging such conceits and has even published a two-volume Dictionary of Fun Movie Clichés. Drawing on this vast inventory, Djuna peppers Counterweight with nods, explicit and sly, to movies and moviemaking. Green Fairy spies operate a lab that uses “the latest in Hollywood technology.” A “pair of ‘filming’ spaceships” shoot a “space-war reality show.” A scientist tortures Choi Gangwu by pulling “a giant iron lever that looks like it’s been repurposed from Dr. Frankenstein’s lab.” (In the title story of one of Djuna’s most popular collections, “The Bloody Battle of Broccoli Plain,” space vessels are known as Garbos, Dietrichs, Adjanis, and Deneuves.) Djuna is clearly having fun, but as fellow Korean sci-fi author Jung Soyeon has observed, Djuna also “uses the rules and clichés of the genre” to carry out social critique. The exaggerated weirdness of Counterweight functions like a fun-house mirror, except that all the ugly distortions are true.

A decade ago, Djuna described science fiction as the map of “a new body, a new mind, and new desire”—and who doesn’t want to start over? Toward the end of Counterweight, way up in space, Han Junghyuk’s digital “ghost”—a kind of eternal imprint—meets its simulated (but also real-world) expiration. His recollections and dreams play sequentially, like a film, one last time. He sticks a toy gun in his mouth and pulls the trigger. Bam! All of his constitutive thoughts “shatter in an instant. The fragments, like a flock of butterflies, flit off into the air before dissolving into nothing.”

We cannot back down

We now confront a second Trump presidency.

There’s not a moment to lose. We must harness our fears, our grief, and yes, our anger, to resist the dangerous policies Donald Trump will unleash on our country. We rededicate ourselves to our role as journalists and writers of principle and conscience.

Today, we also steel ourselves for the fight ahead. It will demand a fearless spirit, an informed mind, wise analysis, and humane resistance. We face the enactment of Project 2025, a far-right supreme court, political authoritarianism, increasing inequality and record homelessness, a looming climate crisis, and conflicts abroad. The Nation will expose and propose, nurture investigative reporting, and stand together as a community to keep hope and possibility alive. The Nation’s work will continue—as it has in good and not-so-good times—to develop alternative ideas and visions, to deepen our mission of truth-telling and deep reporting, and to further solidarity in a nation divided.

Armed with a remarkable 160 years of bold, independent journalism, our mandate today remains the same as when abolitionists first founded The Nation—to uphold the principles of democracy and freedom, serve as a beacon through the darkest days of resistance, and to envision and struggle for a brighter future.

The day is dark, the forces arrayed are tenacious, but as the late Nation editorial board member Toni Morrison wrote “No! This is precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.”

I urge you to stand with The Nation and donate today.

Onwards,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

The Perils of a Post-Racial Utopia The Perils of a Post-Racial Utopia

In Nicola Yoon’s One of Our Kind, a dystopian novel of a Black upper-class suburb’s secrets, she examines the dangers of choosing exceptionalism over equality.

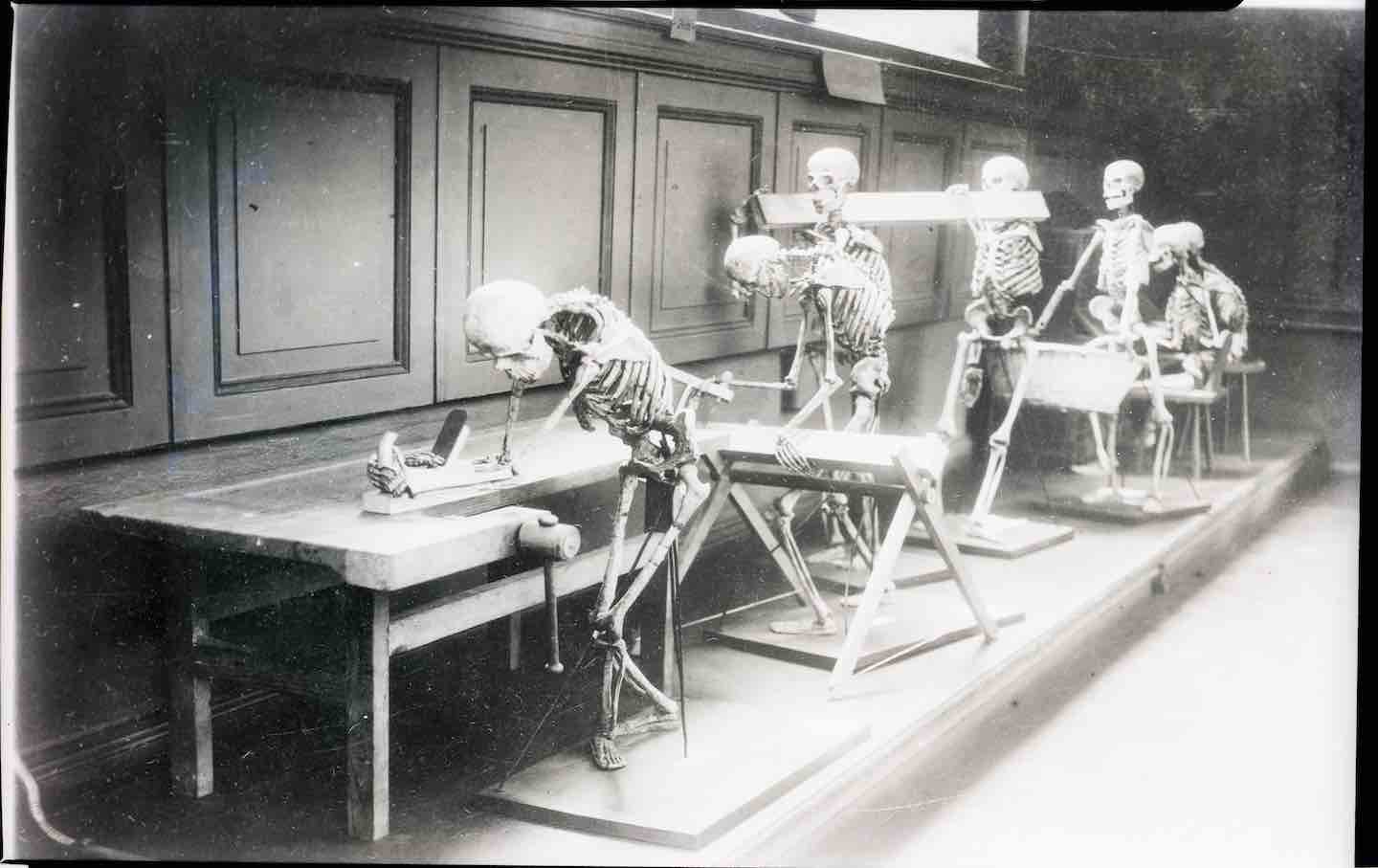

Why Americans Are Obsessed With Poor Posture Why Americans Are Obsessed With Poor Posture

A recent history of the 20th-century movement to fix slouching questions the moral and political dimensions of addressing bad backs over wider public health concerns.

Thomas Müntzer’s Misunderstood Revolution Thomas Müntzer’s Misunderstood Revolution

A recent biography of the German preacher and leader of the Peasants’s War examines what remains radical about the short-lived rebellion he led.

Is It Possible to Suspend Disbelief at Ayad Akhtar’s AI Play? Is It Possible to Suspend Disbelief at Ayad Akhtar’s AI Play?

The Robert Downey Jr.–starring McNeal, which was possibly cowritten with the help of AI, is a showcase for the new technology’s mediocrity.

Possibility, Force, and BDSM: A Conversation With Chris Kraus and Anna Poletti Possibility, Force, and BDSM: A Conversation With Chris Kraus and Anna Poletti

The two writers discuss the challenges of writing about sex, loneliness, and the new ways novels can tackle BDSM.

Lore Segal’s Stubborn Optimism Lore Segal’s Stubborn Optimism

In her life and work, she moved through the world with a disarming blend of youthful curiosity and daring intelligence.