Louis Armstrong’s Last Word

Louis Armstrong Gets the Last Word on Louis Armstrong

For decades, Americans have argued over the icon’s legacy. But his archives show that he had his own plans.

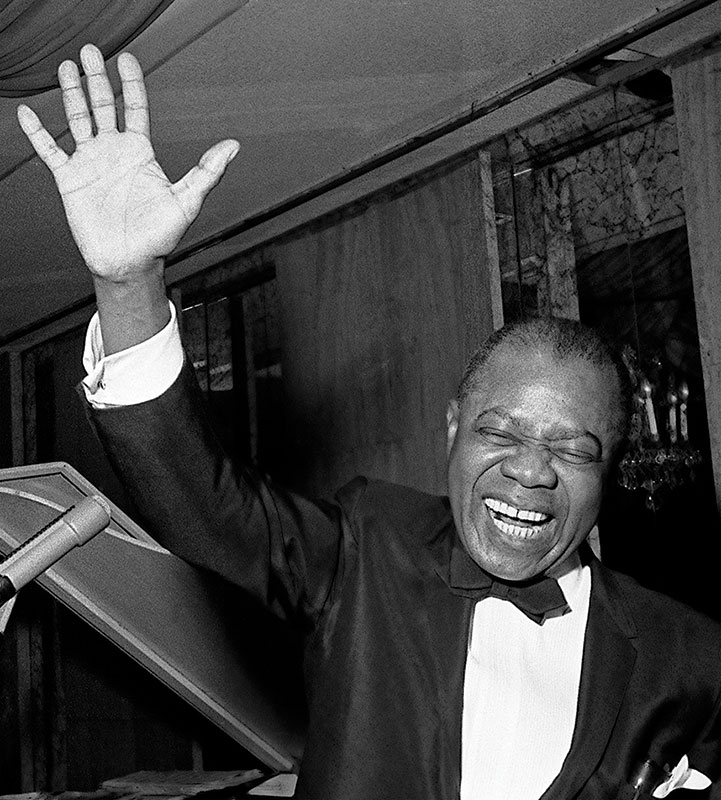

“I get this question all the time,” Ricky Riccardi admitted. The director of research collections at the Louis Armstrong Center looked at me carefully. “Just last week, when I tried to sum up Louis’s life and contribution in an interview, I went on for 28 minutes.”

“Can you give me the five-minute version?” I asked.

Riccardi took a breath. “OK. You can name a thousand great instrumentalists or you can name a thousand great vocalists, but he’s the only person you could find who changed the way people played their instruments and the way people sang. Louis does that in a four-year period in the 1920s; by 1930, if you aren’t playing or singing like him, you’re out of work.

“He was also born at the right time to be a multimedia superstar. Louis was there for acoustic recordings in 1923. After accompanying silent movies, he then made pioneering appearances in film, radio, and television. In many cases, he was the first African American to have featured billing in these new industries.

“He had a rags-to-riches story intimately tied with race. He was born in New Orleans one generation removed from slavery, saw lynchings as a child, then was part of the Great Migration. Eventually, he was in a position to call out a sitting US president, Dwight Eisenhower, over integration.

“He was the soundtrack to the Jazz Age, the Depression, and World War II. In the ’60s, his ‘Hello, Dolly’ took over from the Beatles as the No. 1 hit.

“If you had to pick one person to write the history of 20th-century American culture, it would have to be Louis Armstrong.”

Ever since his seminal first recordings as a leader with his Hot Five and Seven ensembles in the 1920s, jazz musicians have called Louis Armstrong “Pops,” a literal invocation of his role as an ancestor. One of the greatest living practitioners of jazz, the trumpeter Tom Harrell, told me he’d heard a memorable pronouncement of Armstrong’s technical contribution from the saxophonist Phil Woods. Woods—a fluid master of the alto saxophone who is best known to the general public for his solo on Billy Joel’s “Just the Way You Are”—told Harrell, “Louis Armstrong was the first person to play behind the beat on record.”

It’s a strong statement, but one that is borne out by a casual survey of the music recorded by others in the 1920s. Armstrong’s multimedia superstardom was the vessel for this subtle yet epochal reframing of the beat. Indeed, Armstrong’s rhythmic control could be his greatest legacy.

“It Don’t Mean a Thing (if It Ain’t Got That Swing),” as the Duke Ellington song puts it. There is no easy or agreed-upon definition of “swing,” but part of it seems to be how the musicians in an ensemble don’t play on quite the same rhythmic track. In the simplest terms, “behind the beat” means that the melody is a shade slower than the accompaniment. This effect gives another kind of ecstasy to the overall rhythmic feel. Armstrong was surely not truly the first to use behind-the-beat phrasing; the practice runs back through the Afro-Latin diaspora. But the anointed ambassador of the American mix was Armstrong. As his fame grew, as he became the symbol of American music to the whole world, Armstrong’s beat only got lazier and more confident. He could swing a whole band of the squarest cats all by himself.

It was almost an open secret: The beloved, avuncular icon who laughed with Bing Crosby in the movies was also a scientist of rhythm and harmony. None of the serious jazz musicians denied it. “You can’t play anything on a horn that Louis hasn’t played—I mean even modern,” fellow trumpeter Miles Davis told the journalist Nat Hentoff in 1958. In a 1970 birthday tribute in the eminent jazz periodical DownBeat, Quincy Jones wrote, “It’s a shame that anyone takes him for granted, ‘cause everything after John Philip Sousa that swings stems from Louis Armstrong.”

In spite of all this, Armstrong’s reception has long been contested. By the 1930s and ’40s, square white jazz critics claimed that Armstrong had sold out, but the deeper wound was closer to home. During that same period, when Armstrong was a pop superstar in Black communities, columnists in African American papers would debate his performance not as a musician but as the public face of Blackness. Some found a lot to criticize, and this rift would deepen over time.

“One shudders to think that perhaps two generations of black Americans remember Louis Armstrong, perhaps one of the most remarkable musical geniuses America ever produced, not only as a silly Uncle Tom but as a pathetically vulnerable, weak old man,” the critic and historian Gerald Early wrote in 1984. “During the sixties, a time when black people most vehemently did not wish to appear weak, Armstrong seemed positively dwarfed by the patronizing white talk-show hosts on whose programs he performed, and he seemed to revel in that chilling, embarrassing spotlight.”

In this context, it’s little wonder that Louis Armstrong got ready for posterity, carefully taking his legacy into his own hands. According to Riccardi, from 1926 onward, Armstrong and his family made scrapbooks of reviews, photographs, and letters. His wife, Lucille, presented him with his first and last house in late 1943, and that building soon became an archive in waiting. Already an inveterate letter writer, Armstrong started recording home audiotapes in 1950. On the road during that decade, doing hundreds of one-nighters a year, Armstrong toted around a custom-made steamer trunk with two tape recorders and a record player. He would record anybody and everybody while goofing off in his hotel room.

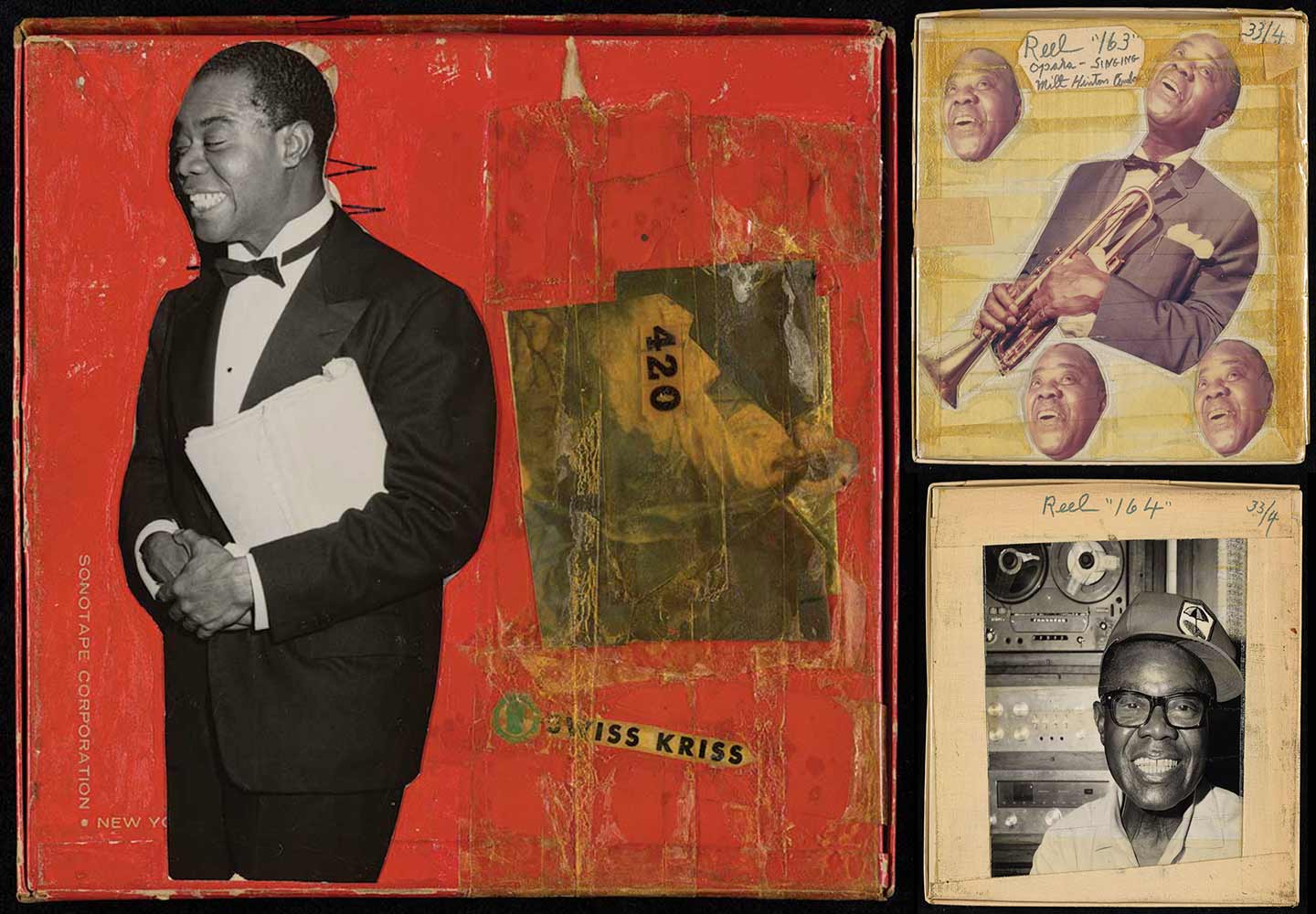

While he slowed down the relentless taping for a time in the 1960s, Armstrong came back for a last act from 1969 until his death in 1971, partly because Lucille bought him two state-of-the-art Tandberg reel-to-reel machines. Armstrong spent hours and hours in his study, creating roughly 200 mix tapes on the Tandbergs and writing down annotated playlists. The reel-to-reel tapes are carefully numbered, and many have artistic covers, usually collages Armstrong crafted by hand. He used his own photos and also cut out images from magazines and “laminated” them with Scotch tape in a homegrown, colorful style. Armstrong wired the house so he could play the recordings in different rooms.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The total collection in the Louis Armstrong Archive numbers more than 60,000 items, including books, records, tapes, photos, letters, and scores. The house, 34-56 107th Street in Corona, Queens, is preserved more or less as it was at the time of Armstrong’s death. “All of Louis’s things are there,” Lucille said at a press conference a month after his passing. “I’m going to keep them there. Eventually, I’ll probably give it to the city as a memorial to Louis. We had planned to do that. People can start coming to see the place where Louis lived.”

Lucille turned the house over to Queens College in 1987, and soon after, the Louis Armstrong Educational Foundation, founded and funded by Louis and Lucille in 1969, donated the archives to Queens College. In 1991, a modern-jazz enthusiast and saxophone player named Michael Cogswell became the institution’s archivist, and in short order oversaw the opening of the archives to researchers and of the house to the general public. Since 2003, countless visitors have been to the Louis Armstrong House Museum to see the studio with the Tandbergs, the living room with the Sèvres vase, and the brilliant blue kitchen boasting a custom Crown stove with six burners.

Cogswell, who died in 2020, spent the better part of his last two decades on another contribution to the Armstrong legacy that was finally realized this year. In 1998, he had enlisted help from the Louis Armstrong Educational Foundation while acquiring an empty lot across the street; this past July, the sleek and modern Louis Armstrong Center, designed by Caples Jefferson Architects, opened its doors on that lot.

I asked Ricky Riccardi if there were any other places comparable to the Armstrong house, museum, and archive. After first drawing a blank, Riccardi eventually arrived at his answer: Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello.

On a sunny day in August, I took my first look at the new building. Moments after I arrived at the center, Riccardi entered, carrying two large bags of takeout from a local restaurant in celebration of a staff member’s birthday. The new consulting archivist, a young man named Matthew Rivera—a former intern with the late archivist and radio host Phil Schaap—followed. Rivera had just collected a parcel of treasure: a collection of photos that Armstrong had sent his onetime drummer, the great Zutty Singleton. According to Riccardi, Singleton and his wife, Marge, were close with a man named Albert Vollmer, who, in addition to being Singleton’s dentist, was a jazz historian and the manager of the Harlem Jazz and Blues Band. After Singleton died, Marge gave many of the drummer’s artifacts to Vollmer, who is now in his 90s and is close with Matthew Rivera. When Vollmer learned that Rivera had become the consulting archivist at the center, he decided to donate Singleton’s photos to it.

Riccardi described the contents to the final arrival to the party, Hyland Harris, a jazz drummer who works as a manager at the center. “I gotta see this!” Harris exclaimed. We all walked in together.

Ricky Riccardi fell in love with Armstrong’s music when he was 15 years old, after encountering tracks from the 1950s like the almost 10-minute version of “St. Louis Blues” on Louis Armstrong Plays W.C. Handy. However, when he went to the library to learn more about his new hero, Riccardi ran into a recurrent harsh theme from the jazz criticism of yesteryear: Young Louis Armstrong was obviously a genius, the story goes, but then he sold out his artistry and became uninteresting after the mid-1930s.

One of the best-known biographies, James Lincoln Collier’s Louis Armstrong: An American Genius, along with Collier’s entry on Armstrong in The Grove Dictionary of American Music, perpetuated this myth of decline, which had become the conventional wisdom; so did the work of the musicologist Gunther Schuller, one of the first scholars to pay serious attention to jazz. That began to change only when, in the early 1980s, the Village Voice jazz critic Gary Giddins was granted access to the archive as he researched his book Satchmo: The Genius of Louis Armstrong. “Schuller scorned two-thirds of Armstrong’s career,” Giddins told me, “expressing disdain for his pop persona and actually suggesting that the government provide him with a stipend so that he no longer had to perform ‘Hello, Dolly.’” That binary opposition, Giddins felt, “completely missed the essence of who Pops was.”

“When I was 17,” Riccardi remembers, “Laurence Bergreen’s book on Armstrong, An Extravagant Life, came out. Bergreen spent 424 pages on Armstrong’s early years and 70 pages on the later years. At that point, a light bulb went on, and I said, ‘Everyone is missing the story of the later years—and that’s going to be the book I write.’” Riccardi’s big idea was deceptively simple: He would tell Armstrong’s story in reverse order, starting with the later years and working his way back.

Following a time at Rutgers University, where he wrote his master’s thesis on Armstrong, Riccardi made his first appointment to visit the archive in 2006. He was delighted by the voluminous tapes of conversations and interviews, which he calls “the missing link.” After three years of constant research, Riccardi took on a position at the museum working under Michael Cogswell. The first installment of his trilogy, What a Wonderful World: The Magic of Louis Armstrong’s Later Years, was published in 2011, followed in 2020 by Heart Full of Rhythm: The Big Band Years of Louis Armstrong, one of the best books on jazz ever written. The week before my visit, Riccardi had handed in a final draft of the concluding volume, tentatively titled Stomp Off, Let’s Go: The Early Years of Louis Armstrong.

The true connoisseurs of jazz history always find each other. We are almost a secret society. Hyland Harris and I have been friends for decades; we met on a gig where I was playing piano and he was playing drums. Cogswell recruited him to the staff of the Louis Armstrong House Museum in 2009, and while Hyland has always been an expert on modern jazz, the archives have proved to be a major education. “I was obsessed with bebop; I loved Charlie Parker,” he says. “Sure, I had heard the Hot Fives and Sevens and even knew some of the Armstrong big band music, but being around the Armstrong universe was humbling. There was so much I didn’t know—I had to dig in. At some point, maybe when they get to be around 40 years old, a lot of serious contemporary jazz players discover Armstrong because they have a new appreciation for melody. That’s what I hear from the cats when they come through.”

The main space in the new center features a glamorous display of “Our Neighborhood,” the large-scale love letter to Queens written by Armstrong near the end of his life. The neighborhood loved him back, and kept tabs on his daily practice: Toward the end of the letter, Armstrong notes that if he didn’t play for a few days, Lucille would get calls asking, “Is Pops okay?”

The bulk of the room is taken up by the exhibit “Here to Stay,” curated by the jazz pianist Jason Moran. It includes significant objects from Armstrong’s life, all the way back to a brick from the juvenile detention facility where he spent part of his adolescence, the New Orleans Colored Waifs Home for Boys, rescued from the rubble in 1965 by the photographer and Armstrong confidante Jack Bradley.

Many of the artifacts on display reached their new home by circuitous paths. When Armstrong was on tour in England in 1934, King George V gave him a trumpet that Armstrong played for years, including on hit records for Decca. In the mid-’40s, backstage at a double bill with the Charlie Barnet Orchestra, Armstrong casually gave the horn away to Barnet’s third trumpeter, Lyman Vunk. Vunk died in 1991, and in his will left the horn to the Armstrong museum. His widow met Michael Cogswell at the subway stop near the house, handed him the horn in a brown paper bag, and got right back on the 7 train.

After showing me around the first floor of the center, Riccardi and Harris took me up in the elevator to see the real riches: every item that has been preserved from Armstrong’s possessions and collections. Riccardi opened the new envelope of photos from Zutty Singleton, which included glimpses of musical history as well as healthy doses of goofing off. A posed shot of the Hot Seven shows only five musicians; Singleton’s inscription on the back explains, “Don Redman didn’t show up and Earl Hines was busy.”

For me, the most thrilling moment came as I looked at Armstrong’s scores. While much general understanding of jazz begins and ends with the idea of improvisation, almost all the jazz greats used piles and piles of sheet music as a clear starting point. However, very few of those scores have surfaced in the history books, even though the ink can offer tangible insights into a complex process. On his chart for the 1938 big band arrangement of “Struttin’ With Some Barbecue,” first recorded by the Hot Five in 1927, Armstrong noted, “ON THE BEAT,” perhaps as a reminder not to phrase the lead too relaxed. The score showed other marks of the everyday life of a working musician, the paper pocked with cigarette burns. On the chart for “Hello, Dolly”—yes, the very page Armstrong read from for his monster hit—he amended the lyrics to include “GOLLY GEE.”

Elsewhere in the archive, there are testaments to Armstrong the thinker, the participant in American civic life who famously spoke out against school segregation in 1957. In 1964, a profile in Ebony included a notorious photo showing Armstrong reading Blues People, a history of jazz in Jim Crow America by the Black radical poet and critic LeRoi Jones, who would change his name to Amiri Baraka the following year. It wasn’t merely a prop—Armstrong’s library includes that very copy of the book. “Louis wasn’t as politically naïve as some might have thought,” Hyland Harris says. “He took his career seriously, and definitely checked out whatever Black people were talking about. At one point, I thought the Ebony spread with Blues People might have just been a photo op, but when I found it in the archive, I knew that Pops had actually read the book.”

There are several trumpets in the archive that were owned and played by Armstrong; Riccardi, wearing white gloves, gently lifted and displayed the brass. When we got to talking about other early jazz greats, including Jelly Roll Morton, a grin shot across Riccardi’s face. “There’s some really extraordinary audio of Louis responding to Jelly Roll Morton’s Library of Congress set,” he said. “It’s like an episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm.”

Riccardi pulled up the interchange, wherein Armstrong listens to audio of Morton extemporizing on jazz history. Armstrong starts off by giving his predecessor a fine spoken intro, but soon hears Morton make an incendiary claim: Louis Armstrong, Morton says, did not invent scat singing. Armstrong stops the tape to correct the record. “I don’t think I’ll let you get away with this!” he begins, insisting that “nobody used the word ‘scat’ in New Orleans” before he came around. “After all,” Armstrong concludes, “I’m still in the business, and you’re still six feet in the ground, young man.”

It’s hard to think of another jazz musician who continues to create contemporary debate like Louis Armstrong. In 2019, Kenyon Victor Adams had a troubled six-month tenure as director of the museum, which, according to The Wall Street Journal, saw “conflict between Mr. Adams and some members of the board of trustees and staff over his vision and management style.” Adams oversaw the removal of a cutout of Armstrong, popular among visitors for photos, from the stoop of the house—not to mention a lapse in employees’ health insurance coverage. As the Journal reported, “Staff and some members of the board had expressed concern that Mr. Adams deviated too far from the museum’s stated mission of focusing on Mr. Armstrong’s life, cultural influence and humanitarian spirit.” In his resignation letter, Adams used current social justice rhetoric: “This kind of opposition, while not unique in museum leadership transitions throughout this city and nation, is a source of harm. And it is a harm that I choose not to endure at this time.” Today, the cutout stands proudly in its place.

It’s been a long time coming. In the 1980s, after Giddins, along with fellow travelers like the writer and archivist Dan Morgenstern, started moving the needle, Stanley Crouch and Wynton Marsalis began waging an all-out initiative to redeem Armstrong. Their most successful incursion was Ken Burns’s widely viewed PBS series Jazz, in which Armstrong is treated with due respect. Last year, a new documentary, Louis Armstrong’s Black & Blues, directed by Sacha Jenkins, used the archival tapes to present a picture of a politically savvy artist who engaged with the world around him.

The current executive director of the center is Regina Bain, who worked for the important scholarship organization the Posse Foundation before taking the reins at 107th Street. When I asked her about the future of the center, Bain lit up, extolling the importance of art, education, and community. “We plan to embrace contemporary artists and musicians who wish to create new works in response to the center,” she told me, giving particular emphasis to “our neighbors here in Queens.” Indeed, Bain made sure that the first gig at the opening of the new building was played by students from the Frank Sinatra School of the Arts in Astoria.

I first heard my own gateway Louis Armstrong album—the marvelous 1959 session Satchmo Plays King Oliver, a tribute to the bandleader and trumpeter who was Armstrong’s mentor—when I was a student myself. I had it on cassette, in a reissue called The Best of Louis Armstrong, and even played the opening track, “St. James Infirmary,” for a presentation in my eighth-grade class. I was drawn to its unlikely mix of dark subject matter—the singer is visiting his dead girlfriend in a morgue—and carefree commentary. I particularly wanted my classmates to hear Armstrong’s amusing spoken asides and chuckles in the breaks between the song’s phrases. A few years later, when the Robin Williams film Good Morning, Vietnam came out, all my classmates were suddenly singing Armstrong’s “What a Wonderful World,” leaving a perfect opening for the comparatively transgressive performance of “St. James Infirmary.”

The day I visited the archive, as if preordained, an original vinyl copy of Satchmo Plays King Oliver was lying on the worktable. I had never seen the LP, nor even discussed the record with anyone as an adult. “This was my first Armstrong,” I said, astonished. “I listened to it over and over!”

“That’s the only record date with video,” Hyland Harris said.

“Want to see it?” Riccardi asked. He dialed up footage of the song “I Ain’t Got Nobody” from the session. I was even more astonished.

I loved this music as a kid, but now I know the history: Armstrong’s 1959 All-Stars were a relaxed and soulful collection of the highest-caliber musicians, and they were redoing some of the tunes Armstrong had cut his teeth on. Since this LP was my introduction to Armstrong, I had never bought into the critical trope that he had lost his way artistically. I always preferred these later remakes to the earlier classics; the sound is much better, and the band is swinging much harder.

On this video, even in a closed studio environment, Armstrong uses all the trademark mannerisms, including smiles and hand gestures, that he did on stage and screen. He plays like he sings, without pretense or artifice. He frequently goes for a big finish at the end—those celebratory high trumpet notes that changed brass playing the world over—but even those moments of climactic theater are absolutely natural, even inevitable.

The pianist on the date is the great Billy Kyle, a cigarette dangling from his lips as he plays. In jazz, the human is indistinguishable from the music. Kyle’s touch, his harmony, and—perhaps especially—his cigarette paint a long-lost, utterly irretrievable picture.

The whole house and museum offer the same kind of effect. Seeing the photos of Armstrong walking through his modernist kitchen, hearing him shuck and jive on tape from the hi-fi in his study: Witnessing the quotidian details of his life only makes his legend all the more imposing and inspiring.

Jason Moran is right to call his installation “Here to Stay.” Last week, while I was working on the edits for this article, I was in Boston teaching at the New England Conservatory of Music. I rode to campus one morning with a Bulgarian Uber driver named Deyan. To my amazement, he was playing Louis Armstrong—and not just the hits like “Hello, Dolly,” either. After somehow acquiring a collection of 65 CDs devoted to air checks and performances from 1945 to 1955, Deyan had uploaded the collection to his phone in order to play it all day for his customers. “I never get tired of the collection,” Deyan told me, “and most of my passengers ask me about what they are hearing. They are all happy to listen to Louis Armstrong.”

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

The Best Albums of 2025 The Best Albums of 2025

From Mavis Staples to the Kronos Quartet—these are our music critic’s favorite works from this year.

Forrest Gander’s Desert Phenomenology Forrest Gander’s Desert Phenomenology

His poems bridge the gap between nature’s wild expanse and the private space of one’s imagination.

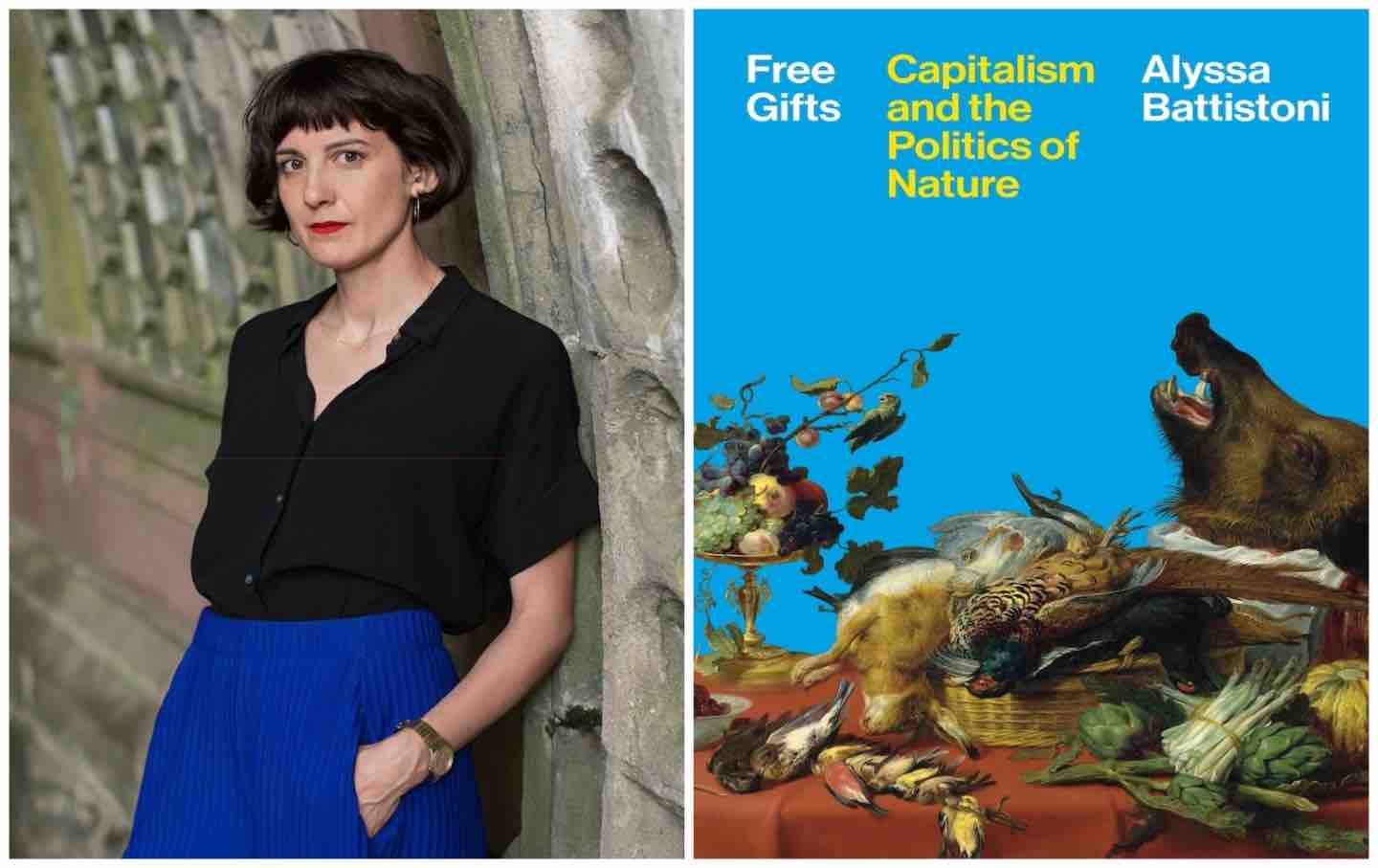

Capitalism’s Toxic Nature Capitalism’s Toxic Nature

A conversation with Alyssa Battistoni about the essential and contradictory nature of capitalism to the environment and her new book Free Gifts: Capitalism and the Politics of Nat...

Solvej Balle and the Tyranny of Time Solvej Balle and the Tyranny of Time

The Danish novelist’s septology, On the Calculation of Volume, asks what fiction can explore when you remove one of its key characteristics—the idea of time itself.

Muriel Spark’s Magnetic Pull Muriel Spark’s Magnetic Pull

What made the Scottish novelist’s antic novels so appealing?

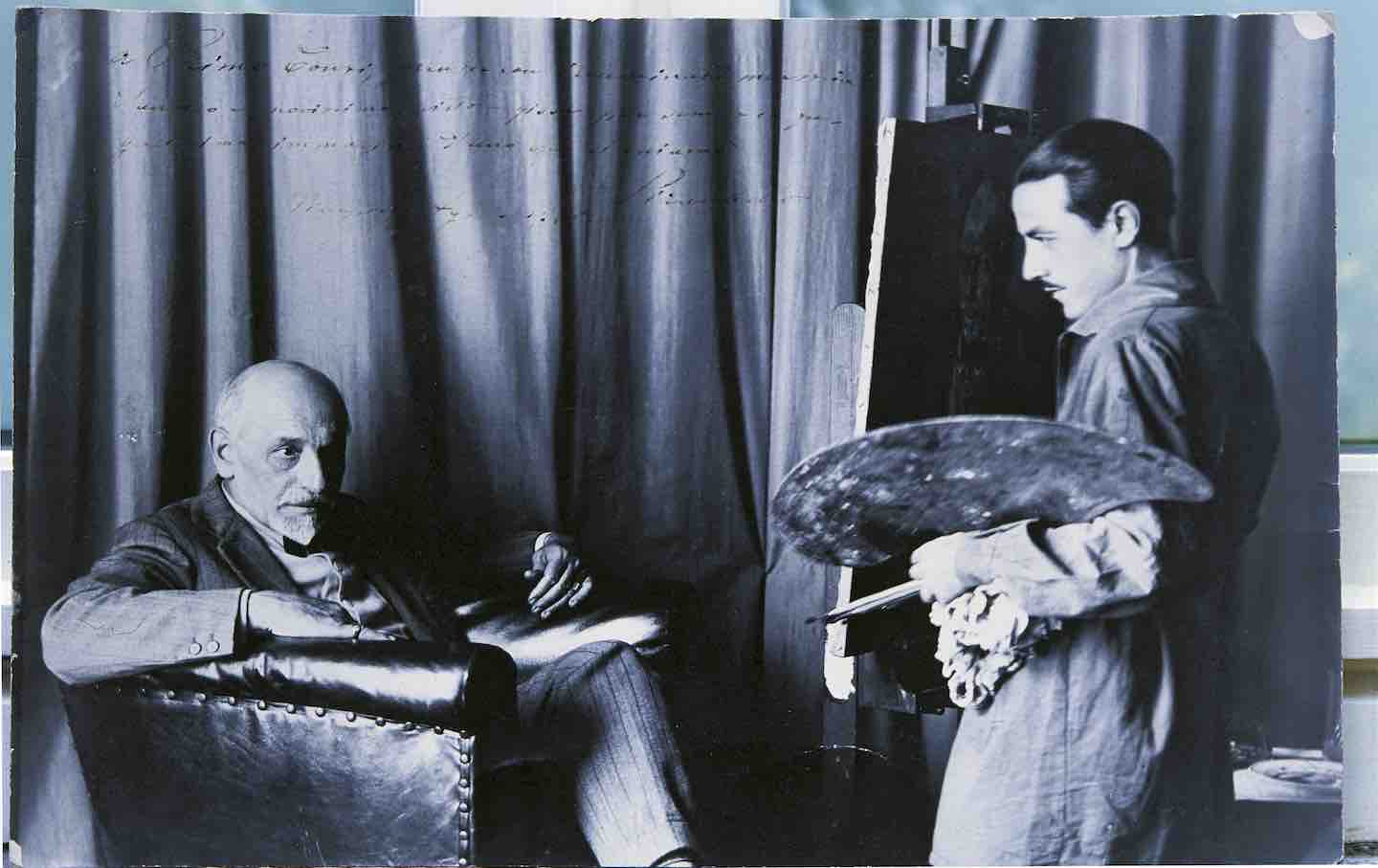

Luigi Pirandello’s Broken Men Luigi Pirandello’s Broken Men

The Nobel Prize-winning writer was once seen as Italy’s great man of letters. Why was he forgotten?