Gaza’s Queer Palestinians Fight to Be Remembered

Through the online platform Queering the Map, stories of queer Palestinians can live on forever, asserting to the world that they do, in fact, exist.

As Israel’s attack on Gaza carries on, Palestinian history is being ripped from existence. Entire family trees are being uprooted and scorched. This kind of annihilation doesn’t just harm the physical body of a people; it attacks their ability to pass on their knowledge, their stories, their customs, and their culture to future generations. As in other genocides, a central intent of this erasure is to eliminate not only lives but a collective memory as well. The loss is incalculable. For queer and trans people in Gaza, already existing on the margins of society, the erasure is tenfold.

Israel’s far-right government, despite aligning itself with homophobic powers around the globe, insists that the Israeli state is a haven for LGBTQ people—in contrast with Palestine, where, it is implied, no queer person could last even a day. This “pinkwashing” is part of Israeli propaganda that erases the existence of queer Palestinians.

Reporting from the Queer Bloc of the recent National March on Washington to Free Palestine, Steven Thrasher writes in Mondoweiss:

But this faux-moral superiority pinkwashes the ways LGBTQ Palestinians are not welcome in Israel (nor, increasingly, in the United States), and it tries to hide the brutality of their lives under apartheid even before October 7. And as if their own governments and religious zealots don’t enact lethal homophobia and transphobia, Israel and the United States’s pinkwashing condemns Palestine as inherently homophobic and transphobic.

Israel’s pinkwashing not only implies that there are no LGBTQ Palestinians but also that they cannot possibly be accepted as they are, where they are. In other words, they must flee to a more “civilized” society, i.e., a white, European one.

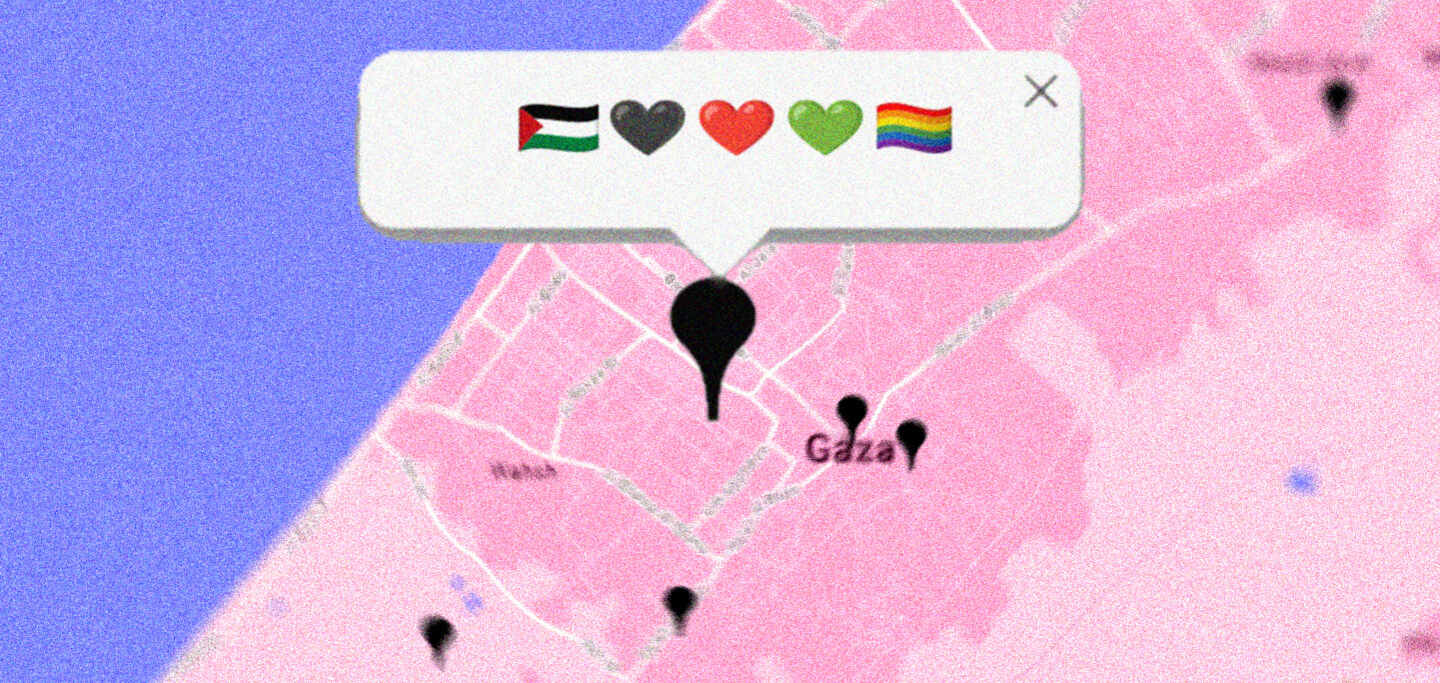

However, LGBTQ Palestinans are finding ways to counter these narratives and make their existence known, even as Israel destroys the world around them. Chief among their outlets is an interactive website, Queering the Map, that allows users to pin stories and memories of their queer and trans experiences all over the world.

The site was launched in 2017 by founder Lucas LaRochelle. Its mission was to gather submissions from queer people and create a global digital archive of queer memory.

In a moment when journalists have been under attack and a blockade on electricity has severely limited the ability of people in Gaza to get their message out, Queering the Map has become an essential tool for queer Palestinians whose stories could have disappeared beneath the rubble altogether.

The entries are equal parts romantic, wistful, and heartbreaking—the testimony of people trying to find love and beauty in a world that wants to erase them from existence.

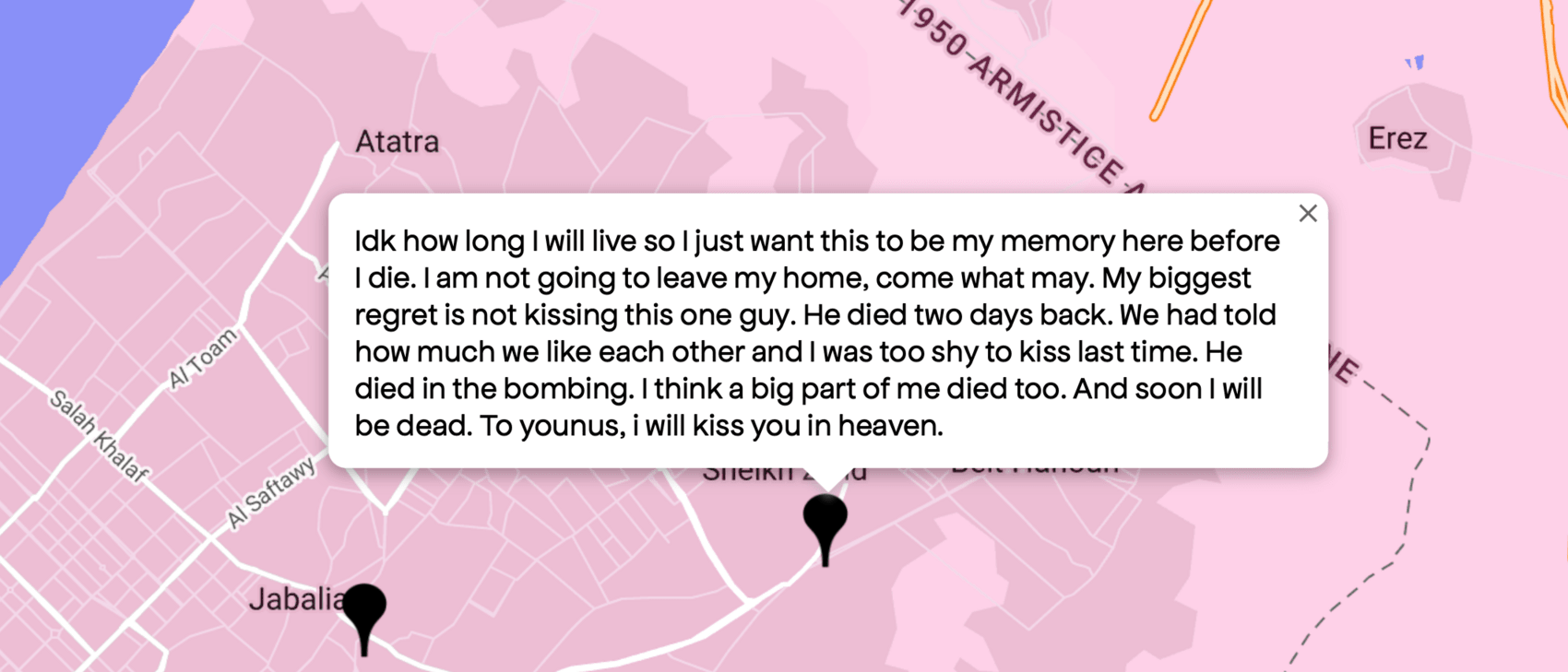

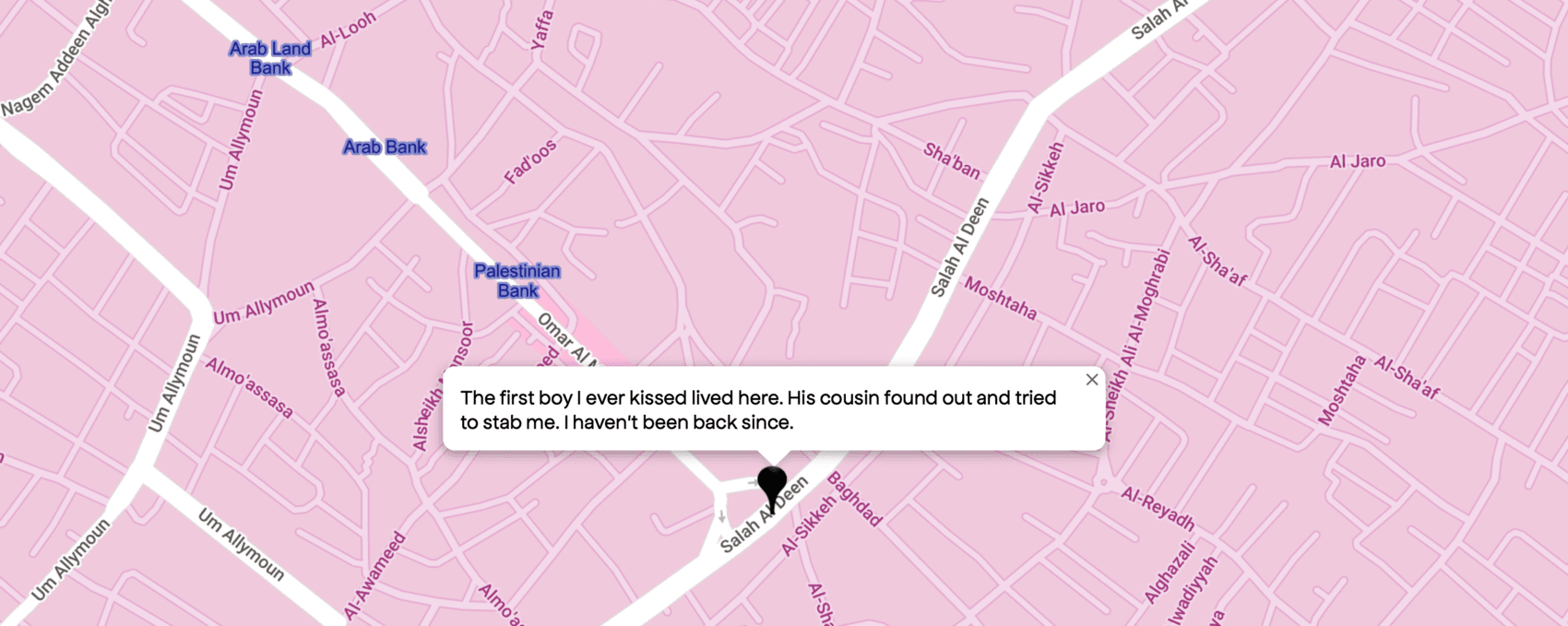

In one submission, someone wrote:

Idk how long I will live so I just want this to be my memory here before I die. I am not going to leave my home, come what may. My biggest regret is not kissing this one guy. He died two days back. We had told how much we like each other and I was too shy to kiss last time. He died in the bombing. I think a big part of me died too. And soon I will be dead. To younus, i will kiss you in heaven.

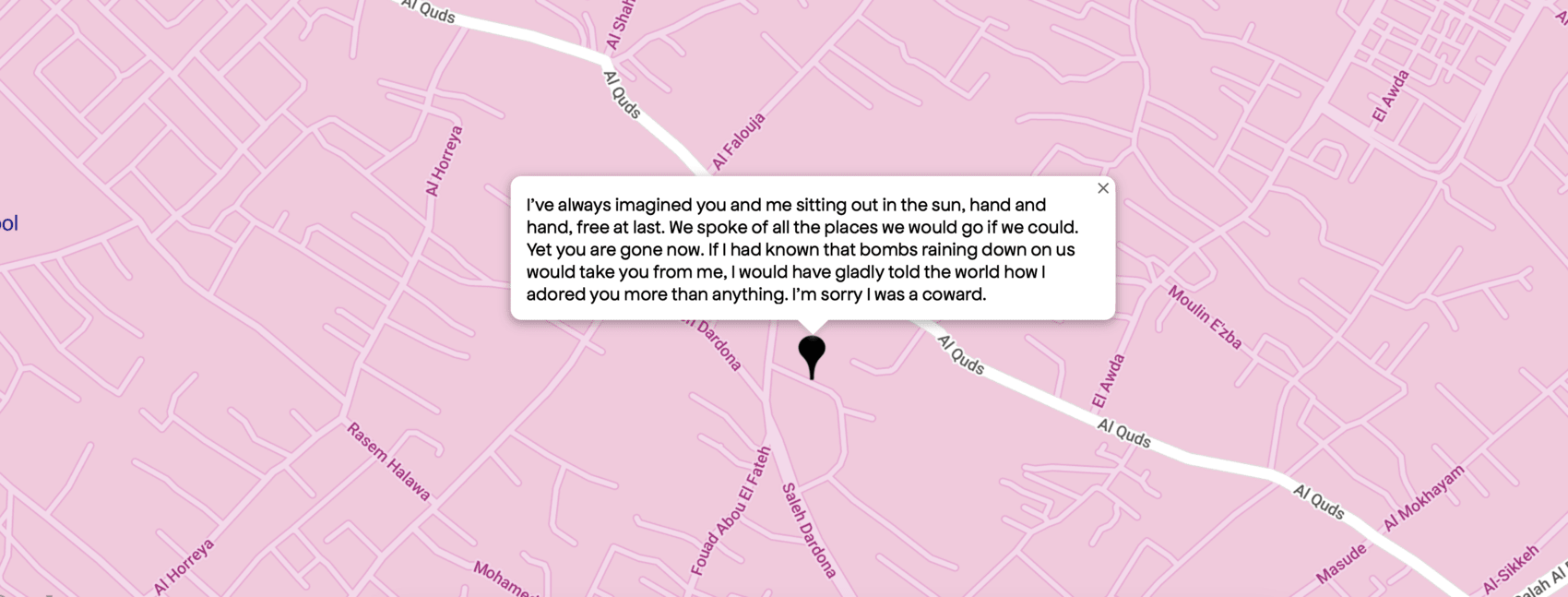

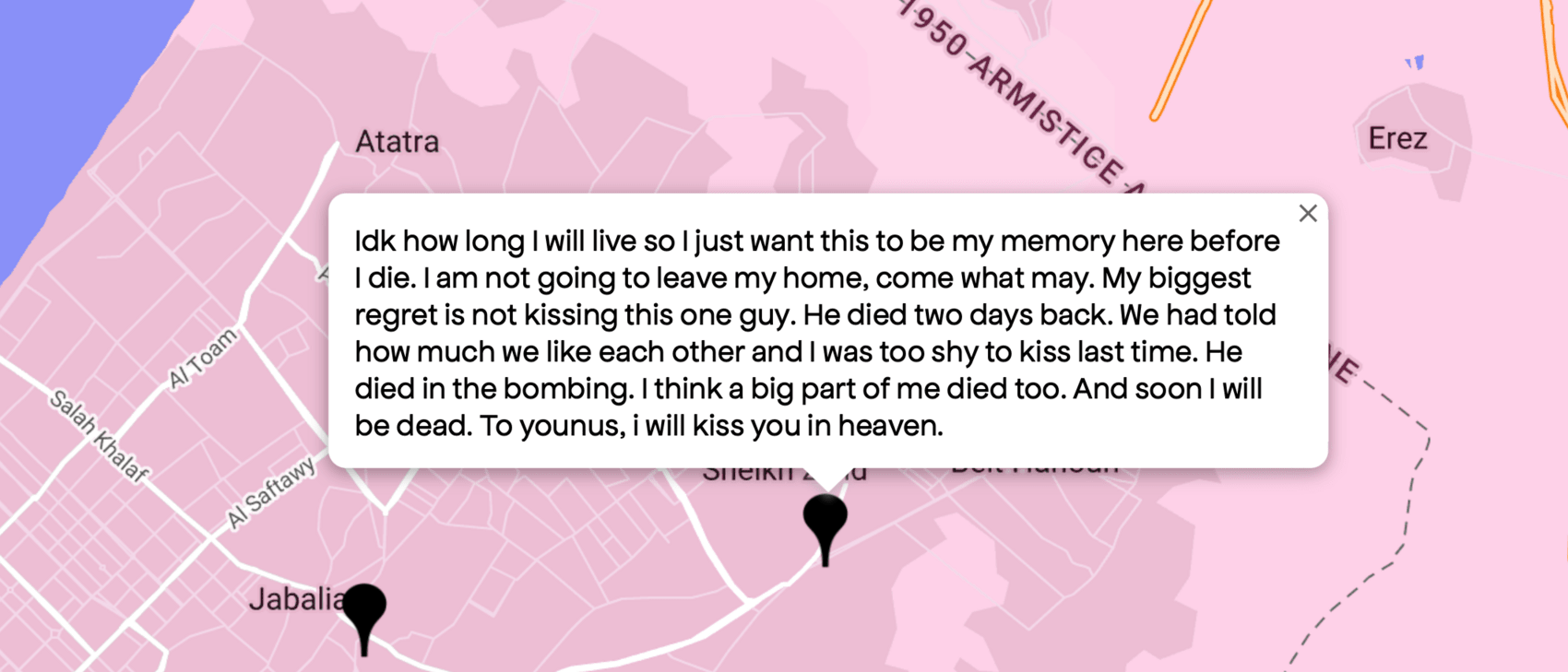

Another wrote:

I’ve always imagined you and me sitting out in the sun, hand and hand, free at last. We spoke of all the places we would go if we could. Yet you are gone now. If I had known that bombs raining down on us would take you from me, I would have gladly told the world how I adored you more than anything. I’m sorry I was a coward.

In just a few short lines, these anonymous Palestinians were able to capture all that is lost when people are annihilated. Each of these submissions is pinned to Gaza, though the date they were uploaded to the platform is unknown.

Israel conducted air strikes on the Gaza Strip throughout 2022; a three-day attack in August 2022 killed 46 Palestinians and wounded 350 people.

It’s hard to discern which specific Israeli missile killed the lovers and crushes these submitters write about, highlighting the ongoing trauma from Israeli military bombardments faced by Palestinians in Gaza.

Another post reads:

A place [where] I kissed my first [crush]. Being gay in Gaza is hard but somehow it was fun. I made out with a lot of boys in my neighborhood. I thought everyone is gay to some level.

![“A place [where] I kissed my first [crush]. Being gay in Gaza is hard but somehow it was fun. I made out with a lot of boys in my neighborhood. I thought everyone is gay to some level.”](https://www.thenation.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/my-first-crush.jpg)

Unsurprisingly, many struggle to hold the two identities as able to coexist. Commenting on some Palestinian screenshots on Queering the Map’s official Instagram page, some have posed questions like, “How [do] queers support Palestine knowing they will execute them for their identity at the first opportunity?” and “Maybe visit Palestine and check if it’s not punishable by death, Yell ‘Slayyyyy’ when you get there they love it.”

These comments deliberately overlook the more immediate punishment, the collective punishment for being Palestinian in the Gaza Strip, the West Bank, or even Israel. More than 11,200 people, including over 4,000 children, have been killed in Gaza since October 7. These comments deflect from the executions that are happening every 15 minutes as Israel continues relentless air strikes on Gaza, with illegal chemical weapons like white phosphorus. Comments like these rely on racist tropes about Palestinians to deflect from the violence all Palestinians are subjected to. Tropes that green-lighted journalistic malpractice when unverified reports of Hamas beheading babies circulated in mainstream media—which were later retracted by the White House. Tropes that are directly responsible for the current ethnic cleansing of Gaza. People are being decapitated in Gaza, not for being queer but for being Palestinian.

In an article about Pinkwashing, Al-Qaws, a Palestinian civil-society organization for Sexual and Gender diversity, writes:

When queer Palestinians are spoken about by Israel’s defenders, it is only to paint a portrait of individual victimization that reinforces a binary between Palestinian backwardness and Israeli progressiveness. These portrayals suggest that Palestinian society suffers from pathological homophobia, and that no dissenting voices could ever survive for long within it. Pinkwashing tells queer Palestinians that personal (and never collective) liberation can only be found by escaping from their communities and running into their colonizer’s arms.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →By painting Palestine and Palestinians as intrinsically homophobic, Palestinian resistance is framed as antithetical to queer liberation, while Israeli occupation is a form of queer salvation. In fact, Israeli security forces have admitted to deliberately threatening and outing queer Palestinians as a tactic to intimidate them into working as informants.

Communities of color in the US know the ramifications of transphobic and homophobic scapegoating. People of color are often depicted as innately more homophobic than their white counterparts. Yet, when Black trans people are murdered across this country with impunity, or when state governments pass policies that force families with trans children to leave their homes for safer cities, we don’t insist that these places be decimated for their violent views. When it’s not the Global South we’re talking about, we tend to be better able to understand that transphobic and homophobic violence are not reflective of the whole.

Witnessing Queering the Map in a time of war, brings to mind another map created from a need for self-definition against US war propaganda. In 2010, Iraqi artist Wafaa Bilal created a performance piece “and Counting…,” where his back was tattooed with dots for each Iraqi killed by the US, and to challenge American desensitization to the catastrophic loss of Iraqi life during the height of the Iraq war. The piece was performed over the course of 24 hours in a New York City gallery. He was not able to tattoo all 100,000 dots representing Iraqi’s killed (a conservative estimate—some say the toll is closer to 1,000,000) before running out of space on his back. Bilal sought to commemorate the dead as well as challenge American audiences to interrogate their relationship to the people they typically saw as simply statistics. He did not have the luxury of distance from these numbers; his own brother, Haji Bilal, was killed by a US air strike in 2004.

Wafaa Bilal’s tattooed map was in direct conversation with another kind of tattooing that had been taking place across Iraq. As a result of the sheer carnage brought by the American military, Iraqis, especially young men tattooed parts of their bodies with their names and various forms of identification, in hopes of making it easier for their loved ones to identify their bodies when the time came.

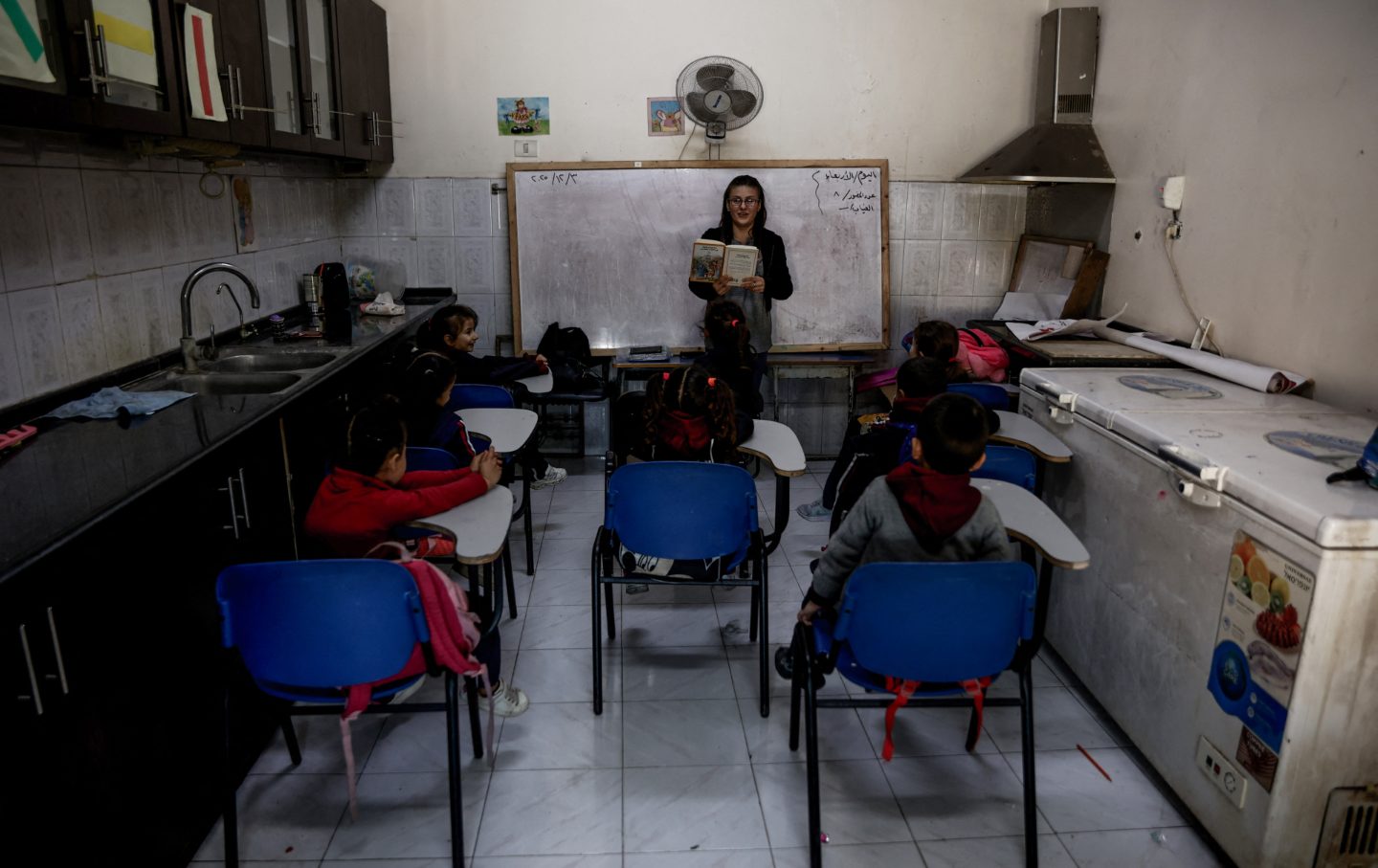

In October, videos circulated of small Palestinian children mapping their own bodies with permanent markers, taking a cue from the young people of Iraq who used tattoo guns to alleviate the psychic suffering their family members would endure when they went searching for body parts to bury. The videos of the children, gathered in groups, writing their names as their young minds are forced to reckon with the end of their short lives, are heartbreaking. The images of children’s dead bodies with their names stretched across their still limbs are harrowing.

It is vital to unravel the misinformation that keeps people consenting to wars where thousands of children are deemed acceptable “collateral damage.” It is vital that these children stop being forced to write their names and their little siblings’ names on their arms, so they may live long enough to feel their own heart flutter after meeting a new crush. So they can know the uncertainty of tingling fingertips as you try to decide whether or not to reach for their hand. So they might someday experience all of the ways one can love, and some can even write their own memories into queer archives.

Queering the Map can be seen as a digital version of this act of memory-keeping for queer people as their loved ones are killed and the end of their own life feels imminent. More than the shocking horror of seeing their bodies mutilated by Israeli missiles, the memories of Palestinians in Gaza become a connective tissue for people like myself, who have also had first crushes, and been in love, and had to hide it for a myriad of reasons.

I read these stories and grieve the people whose desperate fingers typed them. I think about them and wonder if they have survived the US-funded Israeli airstrikes. If they will be able to leave new notes on this Queer Map. If they will be able to rebuild Gaza in their image, with their love and memories. If they will one day be free of occupation travel restrictions to wander the globe and experience the different pulses of queer communities, and come back home to Gaza, sharing their stories with dear friends. Reminiscing over the parties they went to, the people they kissed, the meals they shared, the queer memories they made. Or if they have already joined the loves they wrote of in the next realm. If they are together, fingers intertwined, walking the shoreline of a Gaza that isn’t mapped by bombs.

In a way, the anonymous Gazans’ whose stories are pinned on Queering the Map, are asking us to do more than bear witness. They are asking us to love their loves with them. To hear our own stories in their stories. To love them. Adore them. And thus, be haunted by what we have allowed them to become.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation