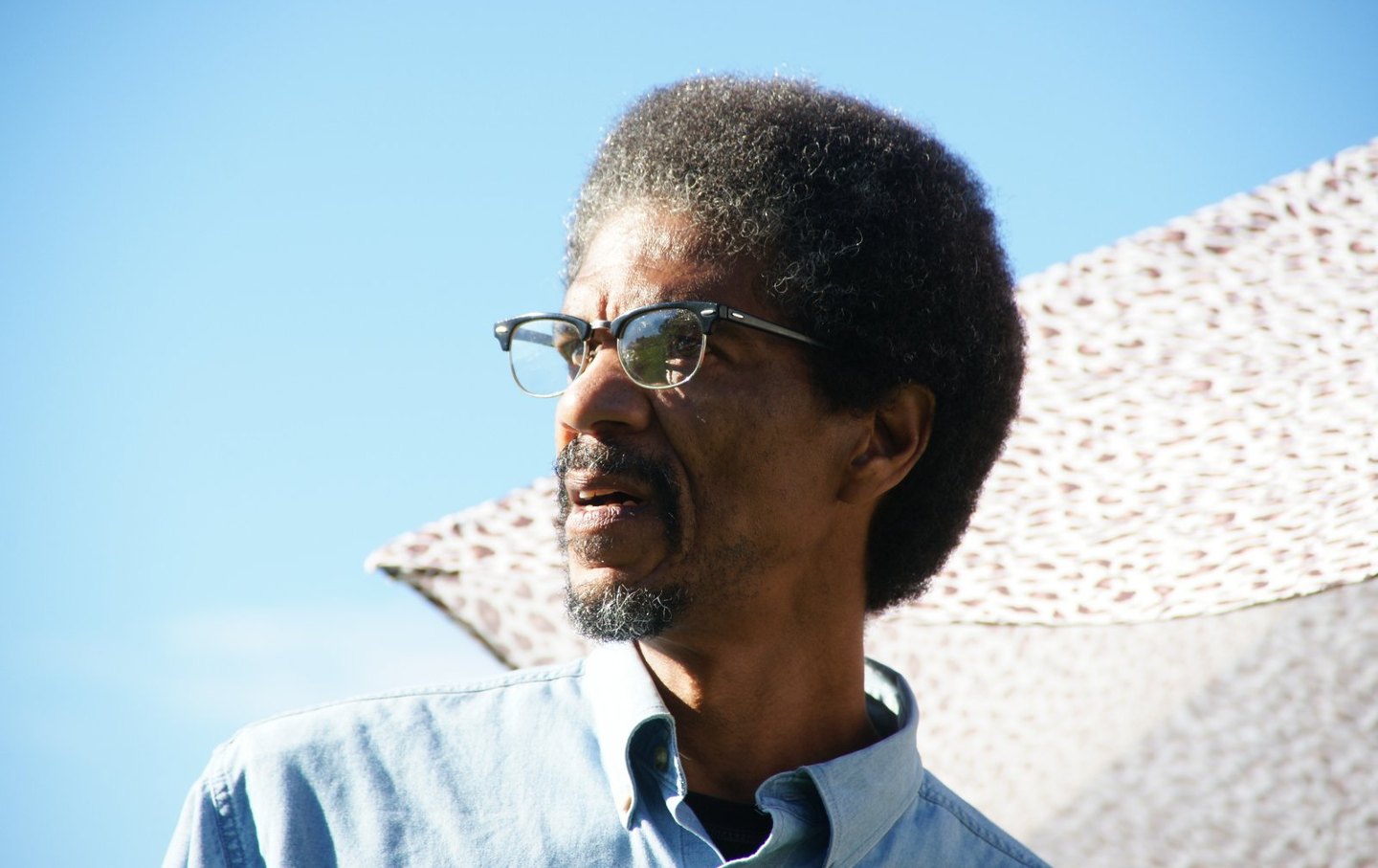

In a world accustomed to mass death, it is tradition at year’s end to commemorate individual losses, without which the scale of human grief is barely comprehensible. This year, The Nation lost a friend and writer, a source and sometime antagonist, a fierce and tender comrade in Kevin Alexander Gray, who died suddenly on March 7 in Columbia, S.C. He was a black man in America, dead at 65.

Chances are that any reporter covering presidential elections—particularly the Democrats’ “Black Primary” in South Carolina—would at least have met Kevin Gray, if not had a talk and gotten a primer on the peculiarities of the state. He had spent his life there, and having once had a job that sent him to every county, he knew not only its players (and their political genome) but also the creases of its history and folkways, as well as the origins of countless black figures who had fled. Kevin stayed. He stayed and called himself “kind of a hippie guy” in outlook. Stayed and ran Black News in Columbia. Stayed and did retail politics, ousting racist sheriffs, electing some progressives. Stayed and burned a conjoined Confederate/Nazi flag on Gervais Street when the statehouse flew the slavers’ battle standard. Stayed and for 20 years chaired the state ACLU, for which he was the public face of lawsuits and support for anyone exercising free speech and seeking equal treatment. Stayed and opposed violence and war, though he’d been an army captain. Stayed and suffered neither fools nor stereotypes.

Kevin observed the world—traveled, physically and intellectually—and translated it for local audiences; then he used place and personal experience as starting points when writing or speaking about politics and culture nationally, in print, on radio or television. He could talk with anyone. And could he talk… weaving political analysis and movie lines, scholarship and street wisdom, storytelling and common cussing. His voice was mellow, and stinging. He’d say he liked to keep things simple. His curiosity was anything but: “I try to understand why we relate to one another the way we do, why we say the things we say and do the things we do, and what it may lead us to,” he wrote.

Moving around the state, he’d chat with strangers; invariably it turned out he knew exactly where their momma grew up, or how their labor figured in history. Early on, he’d set a goal to meet everyone who had worked with Dr. King. So, he met Jesse Jackson, with whom he had an enduring, sometimes contentious, deeply felt relationship. He helped build the Rainbow Coalition. In 1988 he coordinated Jackson’s South Carolina campaign for the presidential nomination, delivering the state for “my homeboy.”

“Glorious” is how he characterized the Rainbow experience. Kevin loved King’s 1967 “triple evils” speech—included an excerpt on a mix tape with “Ghetto Vet,” Malcolm X and “Everything Is Everything”—which defined the essential task as a unified struggle against “racism, economic exploitation and war.” On that basis, in 1984 the Rainbow stitched together pieces of the fractured left in a Black-led social movement electoral campaign. It brought Kevin lifelong friends Steve Cobble and Frank Watkins: like him, background guys much-consulted by political journalists; like him, both now gone. It brought Kevin detractors, chiefly hack preachers who fancied themselves arbiters of black politics and remained embittered, for decades, because he’d seated gay activists or Central America solidaristas or Palestinians or poor and peace people instead of them as 1988 convention delegates. Jackson had said he wanted a delegation that reflected his coalition; Kevin was one of the people who made sure it did.

In death, Kevin Gray was sometimes remembered as “fearless.” And sometimes as “an entrepreneur” with edges rubbed smooth because he ran a barbecue restaurant. Kevin never would so reduce life. He opened Railroad BBQ in 2020, and adorned it with black, Southern, political ephemera for many reasons but not as an endpoint. Memory mattered. He’d grown up in the segregated South and brooked no contemporary arguments suggesting maybe it wasn’t so bad. It was the place his father, Paul, had fled, but to which he returned with his children; the place his mother, Geneva, sought to change, sending Kevin and his sister Valerie to desegregate the local school in Spartanburg; a place whose violence the family endured and absorbed. Kevin’s optimism and humor were as much tools for survival as they were features of his personality. When Richard Pryor died, Kevin wrote a tribute calling the comic genius “a mirror”: “His comedy was rooted in his and our fears. And he dealt with those fears in some screwed up ways just like the rest of us. To confront fear isn’t fearlessness, it’s courage.” He called this his favorite essay in his collection, Waiting for Lightning to Strike.

People respected Kevin for the same reasons he admired Pryor. He kept it real, and reality is messy. The night Barack Obama won the 2008 South Carolina primary, Kevin was under the TV lights, being interviewed. He distrusted Obama as a neoliberal “smoothy-doovy” and would be an unsparing critic, but he also understood not only the mechanisms by which the campaign succeeded but the reasons behind voters’ dreams. An old man watching from a distance, a security guard, asked, “Is that Kevin Gray?… I want to thank him for all he’s meant to us.” And Kevin met the old man, and they talked a long while beyond the glare.

We cannot back down

We now confront a second Trump presidency.

There’s not a moment to lose. We must harness our fears, our grief, and yes, our anger, to resist the dangerous policies Donald Trump will unleash on our country. We rededicate ourselves to our role as journalists and writers of principle and conscience.

Today, we also steel ourselves for the fight ahead. It will demand a fearless spirit, an informed mind, wise analysis, and humane resistance. We face the enactment of Project 2025, a far-right supreme court, political authoritarianism, increasing inequality and record homelessness, a looming climate crisis, and conflicts abroad. The Nation will expose and propose, nurture investigative reporting, and stand together as a community to keep hope and possibility alive. The Nation’s work will continue—as it has in good and not-so-good times—to develop alternative ideas and visions, to deepen our mission of truth-telling and deep reporting, and to further solidarity in a nation divided.

Armed with a remarkable 160 years of bold, independent journalism, our mandate today remains the same as when abolitionists first founded The Nation—to uphold the principles of democracy and freedom, serve as a beacon through the darkest days of resistance, and to envision and struggle for a brighter future.

The day is dark, the forces arrayed are tenacious, but as the late Nation editorial board member Toni Morrison wrote “No! This is precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.”

I urge you to stand with The Nation and donate today.

Onwards,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation