The Medieval-ness of Mark Zuckerberg

There’s something very feudal about his massive doomsday bunker.

In December, Wired released an in-depth investigation detailing the alarming extent to which Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg has bought up the Hawaiian island of Kauai since 2014. The billionaire hasn’t just scooped up land on the island but power, as his parasitic philanthropy has undermined the regulatory oversight of local government. And now he’s also constructing a sprawling, secretive compound known as Koolau Ranch. It’s a standard-issue paranoid billionaire apocalyptic fantasy, replete with farms, a Swiss Family Robinson–esque network of treehouses, and a 5,000-square-foot self-sustaining underground bunker, as well as two mansions “with a total floor area comparable to a professional football field.” While we sadly don’t have images of the mansions, we do have a rendering of the proposed bunker. At first glance, it looks like that often-lampooned New York Times drawing of Osama bin Laden’s cave network mixed with the stale, cubicled, fluorescent-lit office building the guy who does my taxes works in. Once more, Zuckerberg’s aesthetic tastes are best described as the human embodiment of beige, even when he is pouring $100 million dollars into a project (on top of the $170 million he’s already spent on land). This is disappointing to me. If one is to build a ridiculous compound, I feel as though it should at least be as interesting as a famous historical bunker of a different era: the Las Vegas Underground House, a Cold War fever dream featuring a Barbie-pink kitchen and a pool straight out of a mini-golf course.

Yet what strikes me most about Koolau Ranch isn’t its dullness and unoriginality but its sheer medievalness. Zuckerberg is essentially building the Silicon Valley equivalent of a castle. For this comparison, I’d like to focus on the Holy Roman Empire of the 12th and 13th centuries, where power structures were much more decentralized than in the centralized, strictly hierarchical feudalism that had already developed in England or France at the time. During a period of political diffusion, castles like Pettau (now Ptuj Castle in Ptuj, Slovenia) or Münzenberg Castle in Hess, Germany, were very important ways of watching over vast swaths of land and maintaining social and political order.

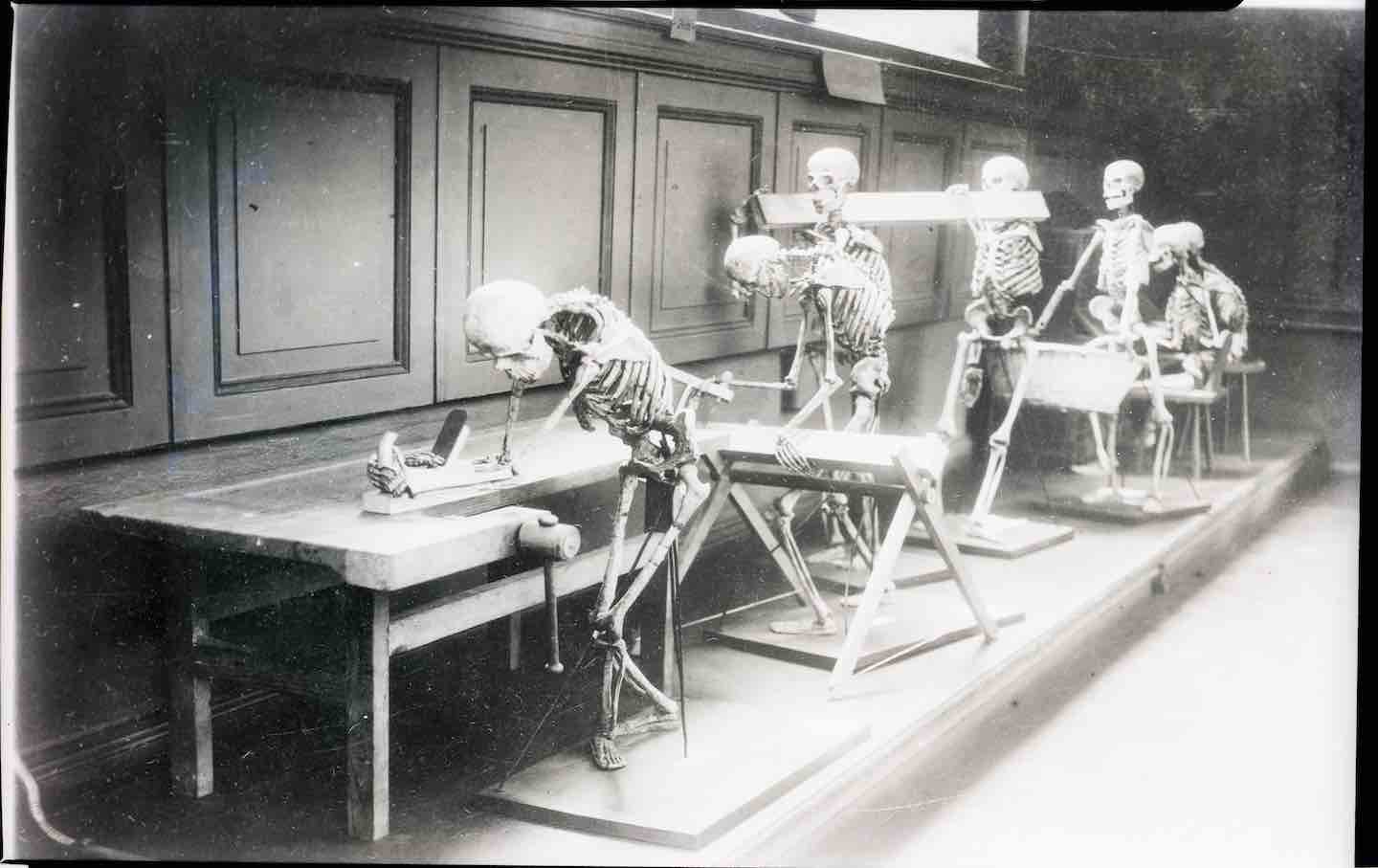

While we think of castles as fanciful, crenellated sites of chivalry, it should be remembered that a castle is not a single building but a collective noun. Castles were essentially closed, self-sustaining systems engineered to survive for weeks under siege. A large castle like Münzenberg typically had an outer and inner ward. The outer ward contained the most important economic and strategic properties, such as smithies for making weapons and armor; bakeries; livestock pens; etc. The inner ward is what is most commonly associated with the term castle, those structures enclosed within the highly fortified stone walls and towers. This space is best defined by two buildings: the palace (the lord’s living quarters) and the keep (the fortified tower for use when the castle came under military threat). The inner ward was often built on steep and difficult to traverse terrain in order to deter enemies, but also to surveil the land—and to be looked upon by subjects. Castles, because they had to be self-sustaining, had their own chapels, wells, and massive kitchens.

Zuckerberg irrefutably operates in a capitalist economic system. But there’s something undeniably feudal about his compound. It’s fortified (by a wall, plus an entire security force), self-sustaining (with farms, food stock, a water source, etc.), built on steep terrain (this, according to Wired, has spurred workplace accidents), and defined by a palatial private space and a survivalist shelter (the two mansions and the bunker). Not unlike a feudal lord, Zuckerberg has cultivated a paternalistic relationship with the land he occupies (through financial rather than sword-based coercion): Wired documents how islanders have taken to petitioning him directly for aid, especially after he provided it during Covid-19.

Zuckerberg’s is a paranoid siege mentality adopted for the technological age. We are living in an era of constant information and surveillance—and no one knows this better than one of the era’s architects. His compound anticipates times of strife and conflict—consequences of the actions of those like him within a sclerotic political and economic system that inflicts untold miseries around the world. While the rest of us face privation and climate displacement, Zuckerberg will be in Hawaii in his mansions (plural) and bunker.

Medieval as his compound is, it’s also informed by a century of technological positivism and a Cold War mentality that never really went away. Belief in technologically self-sustaining architecture pervaded the 1960s and ’70s (another era of intersecting crises). It produced such diverse examples as Alison and Peter Smithson’s plastic, fully automated House of the Future; Walt Disney’s original plans for a planned, self-regulating city known as EPCOT; and more hippie/eco-minded explorations of communes, biospheres, and solar houses. These projects, while diverse in political orientation, were all utopian yet subverted by apocalyptic undertones. The need for a self-sustaining system, after all, presupposes a world that is no longer habitable. It is not surprising that one of the foundational cultural documents of early Silicon Valley culture, the bizarre self-sufficiency magazine The Whole Earth Catalog, originated from such movements and thinking.

Perhaps what is most disappointing is that Zuckerberg ultimately lacks this kind of creativity. That in itself is a late-stage Silicon Valley–ism: Institutions have become rent-seeking bedbugs, sucking the blood from everything of value they’ve built, incapable of generating new ideas outside of wholesale scams and the monetization of every facet of daily life. Zuckerberg is not imagining a better world where humanity is saved from itself by clever engineering. He’s not exploring new ways of living or thinking even on a surface level. He is nothing but a base looter of society, a petty overlord hiding in his castle keep, incapable of imagining anything but a siege.

We cannot back down

We now confront a second Trump presidency.

There’s not a moment to lose. We must harness our fears, our grief, and yes, our anger, to resist the dangerous policies Donald Trump will unleash on our country. We rededicate ourselves to our role as journalists and writers of principle and conscience.

Today, we also steel ourselves for the fight ahead. It will demand a fearless spirit, an informed mind, wise analysis, and humane resistance. We face the enactment of Project 2025, a far-right supreme court, political authoritarianism, increasing inequality and record homelessness, a looming climate crisis, and conflicts abroad. The Nation will expose and propose, nurture investigative reporting, and stand together as a community to keep hope and possibility alive. The Nation’s work will continue—as it has in good and not-so-good times—to develop alternative ideas and visions, to deepen our mission of truth-telling and deep reporting, and to further solidarity in a nation divided.

Armed with a remarkable 160 years of bold, independent journalism, our mandate today remains the same as when abolitionists first founded The Nation—to uphold the principles of democracy and freedom, serve as a beacon through the darkest days of resistance, and to envision and struggle for a brighter future.

The day is dark, the forces arrayed are tenacious, but as the late Nation editorial board member Toni Morrison wrote “No! This is precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.”

I urge you to stand with The Nation and donate today.

Onwards,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation