A Road Trip Through America’s Absurd Political Life

In Sean Price Williams’s debut film, The Sweet East, he pokes fun at the nation’s ideological bubbles.

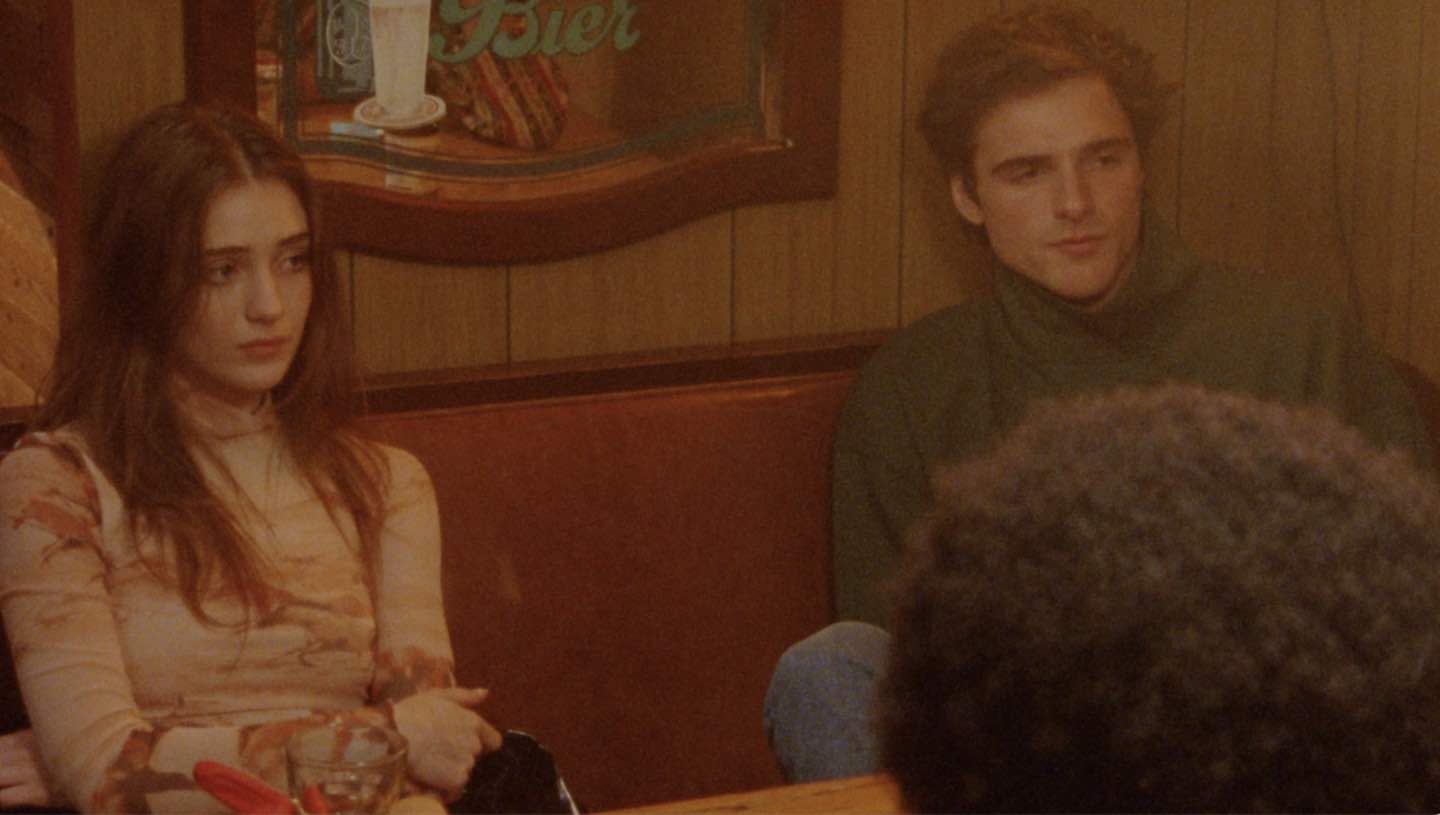

A scene from The Sweet East.

(Courtesy of Utopia)Early in Long Strange Trip, Amir Bar-Lev’s exhaustive four-hour documentary on the Grateful Dead, the venerable jam band’s weary British road manager, Sam Cutler, takes a stab at defining the group’s enduring appeal. “Americans,” he begins, “have got this very, very strange and interesting preoccupation with the discovery of what constitutes America. What it is. In America, people leave home and go out in search of America.” For Cutler, this is a uniquely (and perhaps exclusively) American endeavor.

You don’t really hear about French kids puttering around in a Peugeot “in search of France,” or Tokyo youngsters crisscrossing the archipelago on shinkansen trains looking for Japan. But from touring Deadhead carnivals to films like Easy Rider, Paris, Texas, and Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure—as well as in the enduring idea of the road trip itself—there remains a deep sense that there’s something meaningful to be discovered traversing the vast and varied highways and byways of this preposterous nation. The Sweet East, the debut film from director Sean Price Williams, asks: Well, is there?

The Sweet East is a kind of road movie—albeit one constructed around extended pit stops—across the American Northeast. Talia Ryder stars as Lillian, a disaffected high-schooler who buses up from South Carolina to Washington, D.C., on a school trip. She spends most of the time tooting on a nicotine vape and thumbing around on her smartphone. A class dinner at a notorious pizzeria/ping-pong parlor is interrupted by an unhinged gunman (Andy Milonakis) demanding to see the basement where, he insists, children are being molested. Amid the chaos, Lillian escapes with a punk rock kid (Earl Cave), who entices her into a beat-up van to Baltimore asking, “Fancy a ride to Charm City?”

At a teeming squat, Cave’s “artivist” (his term) gives Lillian a demonstration of his video art experiments. He says that he is trying to render, with his frantic collage of websites and surveillance tapes, the feeling of browsing the Internet as an aesthetic experience. One might say the same of The Sweet East, which feels like a whirling, comic joyride through various contemporary subcultures, which the film regards as more or less equally absurd, be they anti-fascist or antisemitic, art kid or armed wannabe militiaman.

Once the film begins in earnest, as she is hustled away from the pizzeria, Lillian accidentally leaves her phone behind. It’s a smart touch. For one thing, it effectively cuts her off from the outside world. And further, The Sweet East unfolds like a satire in which someone is being whisked through the world of the modern smartphone, where people posture “IRL” as they might on social media, carving out hyper-specific identities, wailing comfortably from within their bubbles. It is a nation (or at least a seaboard) of frauds and poseurs, whom our plucky guide meets with eyes already half-rolled.

From Baltimore, Lillian rolls through the empty industrial land outside of Trenton, N.J., where her new trust-fund, crust-punk friends are eager to spar with a group of neo-Nazis staging a rally. The problem is, the neo-Nazis are nowhere to be found. Separated again, Lillian wanders through the woods and happens upon the rally (really more of a panic), where she meets, and is taken in by, a loquacious academic and closet white supremacist named Lawrence (played by former MTV video jockey Simon Rex). Lawrence takes her to his home, keeps her warm, and dresses her in vintage ladies’ fashions. Lillian wedges a chair against her bedroom door to defend against any potential advances and groans as he rhapsodizes over a screening of D.W. Griffiths’s 1909 biopic of Edgar Allan Poe (“I’m just glad they figured out how to make movies less boring than this,” she complains). His incoherent gripes about liberalism, and the snootiness of more Eurocentric racists, fall on deaf ears. For Lillian, Lawrence is little more than an easy incel mark, happily forking over his AmEx card so she can go on a shopping spree.

On a sojourn to New York City, Lillian ditches Lawrence, only to be picked up by a pair of preening film school wannabes (Ayo Edebiri and Jeremy O. Harris), who decide to cast her in a period piece set around the construction of the Erie Canal. The two regard Lillian’s every utterance as prophetic or otherwise “perfect.” She begins a romance with her pompous English costar (Jacob Elordi), needling him with anti-European insults gleaned from Lawrence. When the film shoot goes awry (in tremendously hilarious fashion), Lillian is spirited away again, this time to Vermont, where she hides out on the property of a group of Islamist militiamen whose training sessions are soundtracked by ’90s Eurodance bangers. As scripted by film critic Nick Pinkerton and realized by Williams, The Sweet East is full of high ideas and low humor, unfolding as some hybrid of Beavis and Butt-Head Do America and Kubrick’s con man epic Barry Lyndon, two films that throw their halfwit heroes into maelstroms of world-historic significance.

Lillian is a bit of a cipher. Like Barry Lyndon (or Butt-Head), she is someone to whom things just happen. The characters she encounters project their personal fantasies onto her. For her part, Lillian seems resistant (or just bored) by these sorts of pestering advances, whether ideological or sexual, though she’s more than happy to use these characters for a free ride, a place to stay, an acting career, or a bummed cigarette.

Many of these men and women clearly want to sleep with Lillian, a perverse (and, in at least one case, pedophilic) desire that she wields to her advantage. Lillian is frustrating, a bit obnoxious, and undeniably crude (her favorite insult, deployed repeatedly, is “retarded”). But she is also wily: able to duck and weave through increasingly ludicrous, perilous situations with a preternatural ease and cunning. Lillian is always on her back foot, but never out of her depth. Rolling with the punches, blasé to a fault, she is something of a stand-in for that American idyll: a blank landscape whom those she meets try to conquer, but who always manages to wriggle out from underneath them. Is she a bundle of untamed potential, or just a vacuous black hole? Why not both? During her brief stint as a starlet, Lillian tells her director, who praises her beauty and brilliance, “I just don’t like, like, being told things about myself.” It is the sense of possibility itself, this mercurial un-pin-downable-ness, that has long drawn adventurers to the road, and it is also why Lillian, empty as she is, might be the ideal wanderer.

It has become something of a cliché for films, television shows, or other fruits of cultural production to be hailed as “what we need right now.” Generally speaking, that urgent need is defined as anti-Trump, counter-MAGA, and basically liberal. Such works are praised as tonics, remedying a political culture that has grown increasingly coarse and divided. The Sweet East offers no such cheap remedy: It is a proudly coarse movie, but that roughness is in the service of mapping a moment that feels both contemporary and eternal. No character that Lillian meets counters the noxiousness of the previous one; they are all self-important, and stupid, in their own unique way. America, after all, has always been a land of con artists and genocidal conquistadors, of hucksters and hacks.

This sort of satire can risk coming off a bit trollish. It can scan as flip, nihilistic, or somehow morally unserious: a self-conscious attempt to rustle the jimmies of the sort of viewer who may find its characters, dialogue, or provocative images (including a set of heavily pierced male genitals) gross or merely trite. Another film may well evoke more sympathy for the anti-fascist shitkickers or the righteous Black art school kids. Another film might not foreground a jaded protagonist so quick to deploy objectionable slurs or afford so much time to a windbag neo-Nazi with frustrated Lolita fantasies.

What makes The Sweet East work is its refusal to even buy into the idea that something like a movie (let alone a small, independent one destined by design to resonate with a selective audience) should somehow resist the politics it skewers: Williams and Pinkerton merely reflect the wonkiest excesses of the culture. The film’s Mad-magazine image of America as a land of craven, bumbling dimwits may not be especially flattering. But it is hard not to be entranced—or at least intermittently amused—by it.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →This may all sound awfully cynical, and it probably is. But it’s cynical in a fresh, frank way. Lillian’s reflex to greet the world with a smirk betrays a weary vigilance, which allows her to survive, and thrive, in the face of predators, would-be captors, and an armed troop of angry neo-Nazis. Her journey through the modern American dream results in no grand disillusionment, because she brooked no illusions in the first place. It is a kind of stunted bildungsroman in which the main character, in all her fuzziness and petty prejudices, is not transformed but rather confirmed. Lillian encounters little that is politically or culturally worthwhile in her adventures. Yet the film’s pace—eased with dreamy languors on the banks of the Delaware River and juiced with occasional bursts of extreme violence—ironically does restore faith in the adventure of America itself.

When Lillian finds herself, in the film’s final episode, safe in the graces of a kindly Catholic friar (Gibby Haynes, the lumbering front man of Texas noise-punk band the Butthole Surfers), who has phoned the police and helps to spirit her back to her worried parents, she cannot help but giggle uncontrollably as he prattles on about a Bethlehem chapel believed to be blessed by a drop of the Virgin Mary’s breast milk. Lillian’s winding journey from the Capitol to some monastery in the wilds of Vermont is wild, exhausting, and at times genuinely frightening. It is also, as her fit of laughter suggests, ecstatic. The people she meets may not embody the better angels of the essential American character (if there is one), but her experience of encountering them proves its own reward.

We need your support

What’s at stake this November is the future of our democracy. Yet Nation readers know the fight for justice, equity, and peace doesn’t stop in November. Change doesn’t happen overnight. We need sustained, fearless journalism to advocate for bold ideas, expose corruption, defend our democracy, secure our bodily rights, promote peace, and protect the environment.

This month, we’re calling on you to give a monthly donation to support The Nation’s independent journalism. If you’ve read this far, I know you value our journalism that speaks truth to power in a way corporate-owned media never can. The most effective way to support The Nation is by becoming a monthly donor; this will provide us with a reliable funding base.

In the coming months, our writers will be working to bring you what you need to know—from John Nichols on the election, Elie Mystal on justice and injustice, Chris Lehmann’s reporting from inside the beltway, Joan Walsh with insightful political analysis, Jeet Heer’s crackling wit, and Amy Littlefield on the front lines of the fight for abortion access. For as little as $10 a month, you can empower our dedicated writers, editors, and fact checkers to report deeply on the most critical issues of our day.

Set up a monthly recurring donation today and join the committed community of readers who make our journalism possible for the long haul. For nearly 160 years, The Nation has stood for truth and justice—can you help us thrive for 160 more?

Onwards,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

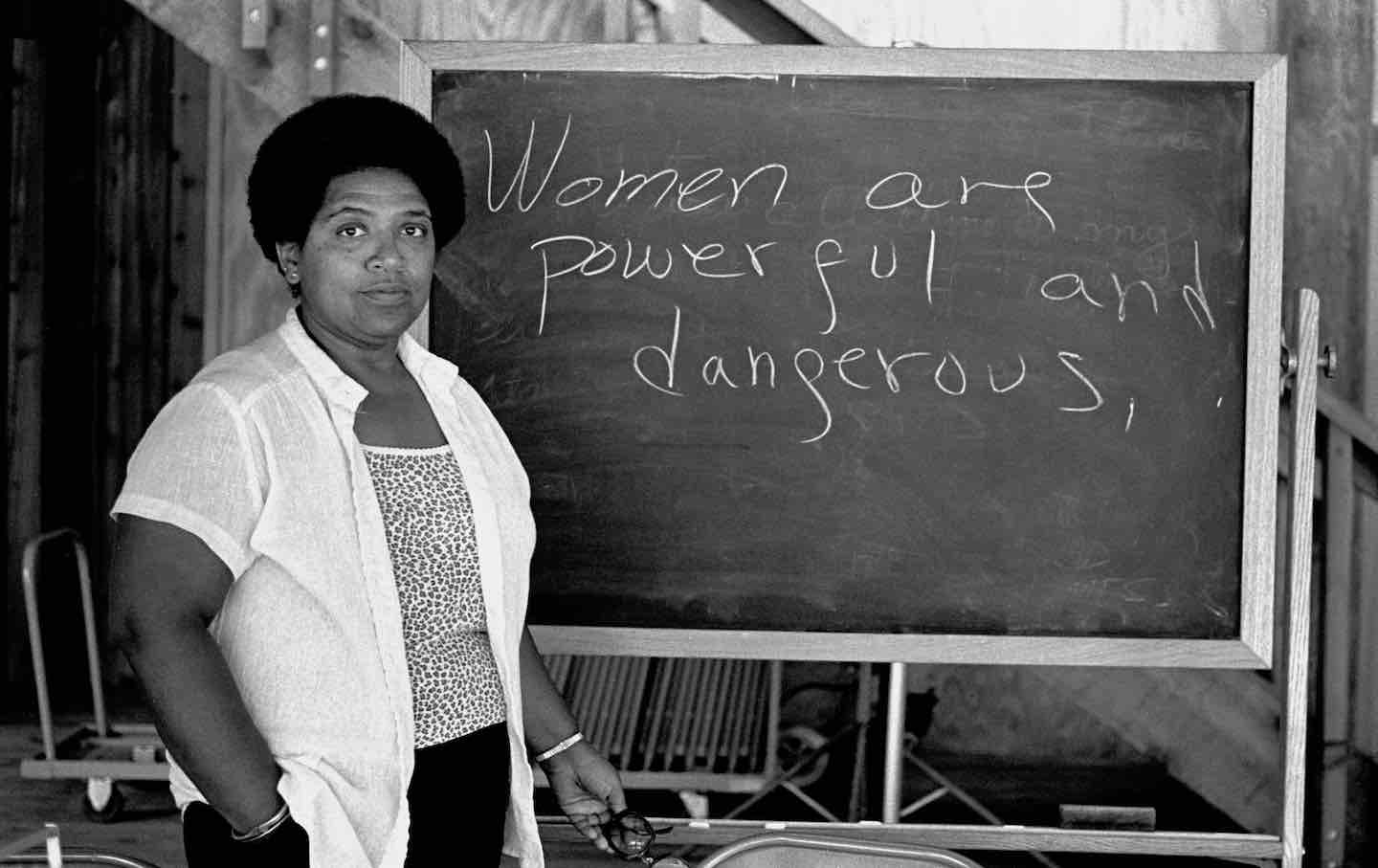

Audre Lorde Has More to Tell Us Than a Handful of Quotes Audre Lorde Has More to Tell Us Than a Handful of Quotes

A conversation with Alexis Pauline Gumbs, one of the world's foremost experts on the Black feminist writer, on her biography Survival Is a Promise: The Eternal Life of Audre Lorde...

The Coming of World Art at the Venice Biennale The Coming of World Art at the Venice Biennale

At one of the oldest biennials on the planet, a glimpse of a more global idea of art history is on view.

Shirley Chisholm Shirley Chisholm

Shirley Chisholm was the first black woman elected to the United States Congress, she represented New York's 12th congressional district from 1969 to 1983.

Move Over Hollywood, Here Comes Chick-fil-A Move Over Hollywood, Here Comes Chick-fil-A

The fast-food giant is poised to move the entertainment world further to the right.

Natasha Trethewey’s Life in Poetry and Prose Natasha Trethewey’s Life in Poetry and Prose

A work of biography, an essay on literature and memory and the South, a prose poem full of lyrical dexterity, Trethewey's latest book is like all of her others: a master study of ...

The Genius of Garth Greenwell The Genius of Garth Greenwell

Set abroad or at home, in unfamiliar worlds an ocean away or in an intensive care unit in Iowa, Greenwell's novels are songs of the self and of the United States as a whole.