Why I’m Running for Commissioner of Agriculture in North Carolina

The health of our state’s democracy depends so much on its agriculture and rural economics.

I’m a crop scientist who’s been working in agriculture for 26 years, and here’s why I’m running for commissioner of agriculture in North Carolina.

Commissioner of agriculture is usually an overlooked role—but it matters tremendously for a state’s economic health, the food system, and democracy at large. Let’s talk about what this job does, why it matters, and why Democratic women with a strong economic message win these races—as Nikki Fried did in Florida in 2018.

In North Carolina, the commissioner of agriculture has two jobs. First, we’re supposed to help our state’s farm economy grow. Second, we handle the health and safety needs related to agriculture. Local meat packing plants? We inspect those. Pesticide use, manure, and other farm materials that can cause trouble when not used properly? We enforce those standards. Bird flu outbreak in our state? We work with farmers to keep it contained.

You can think of a state’s commissioner of agriculture as the shepherd of its food system. But it’s more than that. The health of a state’s democracy depends so much on its agriculture and rural economics.

Rural poverty causes radicalization. So does pollution from farms. Farm radicalization isn’t just a local problem. Farm outfits that hire undocumented workers put serious money behind hard-right legislators and sheriffs who pledge to collaborate with ICE. That means local country politics can get ugly. And those ugly politics don’t stay local. They can undermine democracy for the whole state—as happened here in North Carolina. The ballot fraud in 2018 that made national headlines here? The fraudsters got their start years earlier in an effort to elect an unpopular hardline sheriff in that county—a majority-minority area dominated by the largest hog slaughterhouse in the world.

A commissioner of agriculture who understands both livelihoods and civil rights can make a huge difference. They can build regional and local food systems that grow broad-based wealth. That’s good for a state’s economy and it’s good for democracy. Or like our current state leadership, they can mismanage and dawdle while farm country goes broke. Much of North Carolina’s rural crisis traces straight back to leadership. Our leadership isn’t developing new crops and markets fast enough to keep up with those that are fading out, like tobacco. This drives poverty, farm loss, rural despair, and radicalization in North Carolina—a critical swing state in national elections.

For all the power they hold, commissioner of agriculture races get shockingly little attention. In states like North Carolina where this position is elected, commissioners can run again and again for decades with little real opposition. We’ve had the same commissioner of agriculture for 20 years, despite a series of fumbles and corruption scandals on his watch. He presided over the largest crop insurance fraud ring in US history. His department tipped off meat plants suspected of animal abuse before a “surprise” inspection. His greatest success was encouraging China to buy North Carolina-grown tobacco—only for Trump, for whom the incumbent helped raise funds and votes, to destroy that market with a trade war. Running out of options due to poor leadership, North Carolina’s farmers are resorting to organized crime. And while all this was happening, the incumbent and his aides misspent taxpayer dollars on high-end lodgings and dining.

For all this, urban politicos in North Carolina seem to assume our current commissioner of agriculture will be in office forever. After all, if he keeps winning, farmers must love him, right?

Wrong.

I’m struck by how eager North Carolina’s farmers are for change. It’s not hard to see why. After you account for inflation and population growth, North Carolina’s farm economy has shrunk by 19 percent in the last 20 years. Our farmers and ranchers feel it. And they know what the problem is: corrupt leadership. One hog farmer put it to me this way: “Politicians are a bit like piggies. They’re frisky when they’re little. But then they discover corn and become hogs.” He paused and went on. “Maybe it’s time to put this one in the smokehouse.”

A map of rural North Carolina’s votes bears this out. In 2020 several North Carolina farm counties voted for the Democratic candidate for commissioner of agriculture, and not by a little: Anson. Bertie. Northampton. Hertford. Vance. Hoke. Chatham. Watauga. Halifax. Warren. Edgecombe. Our incumbent doesn’t win because of the farmer vote. After all, farmers are less than 1 percent of North Carolina’s population. Why does he keep winning, then? Suburbs. In 2020, hundreds of thousands of suburban North Carolinians voted for both Joe Biden and a Republican commissioner of agriculture who’s wildly unpopular in much of our actual rural farm country.

It’s one of the greatest ironies of politics. Even when Democrats win the presidential and governor’s seats in North Carolina, suburban voters keep us locked in with a corrupt Republican commissioner of agriculture who’s wildly unpopular in much of rural North Carolina. Why? Because he looks and sounds like what suburbanites think a farmer should look like.

So let’s talk about what I bring to the table. I’ve worked in agriculture and food for 26 years. My job is to sit down with farmers, help them understand their options, and do what’s best for their own livelihood. In that job, I’ve helped family farms and food businesses start growing vegetables in greenhouses. That’s a great livelihood if you get it right—but if you get one detail wrong, you’ll lose your shirt. I’m proud to say every single one of my farm clients is still in business. Altogether, they’re now worth $4 billion. I’ll go toe-to-toe with anyone in North Carolina on that track record.

I know how to help farmers be successful working for themselves—not corporations. I know firsthand the difference that adequate, fair lending makes to every farmer. I know treating workers right makes businesses work better, because people have a chance to put down roots and build skills in their jobs. Bottom line: I know how to do business.

People ask me if it’s hard to work in agriculture as a woman. I wouldn’t know. I haven’t tried it any other way. But I do know that nobody in farm country is surprised that I know how to do business. Rural women have long held the line on making farms work. We’re the ones who balance the family books, take outside jobs, handle invoicing, and turn raw crops and livestock into goods ready for people to buy. We are the business backbone that makes farm country work. I’m proud of what we do. And I’m ready to do it for all of North Carolina.

We cannot back down

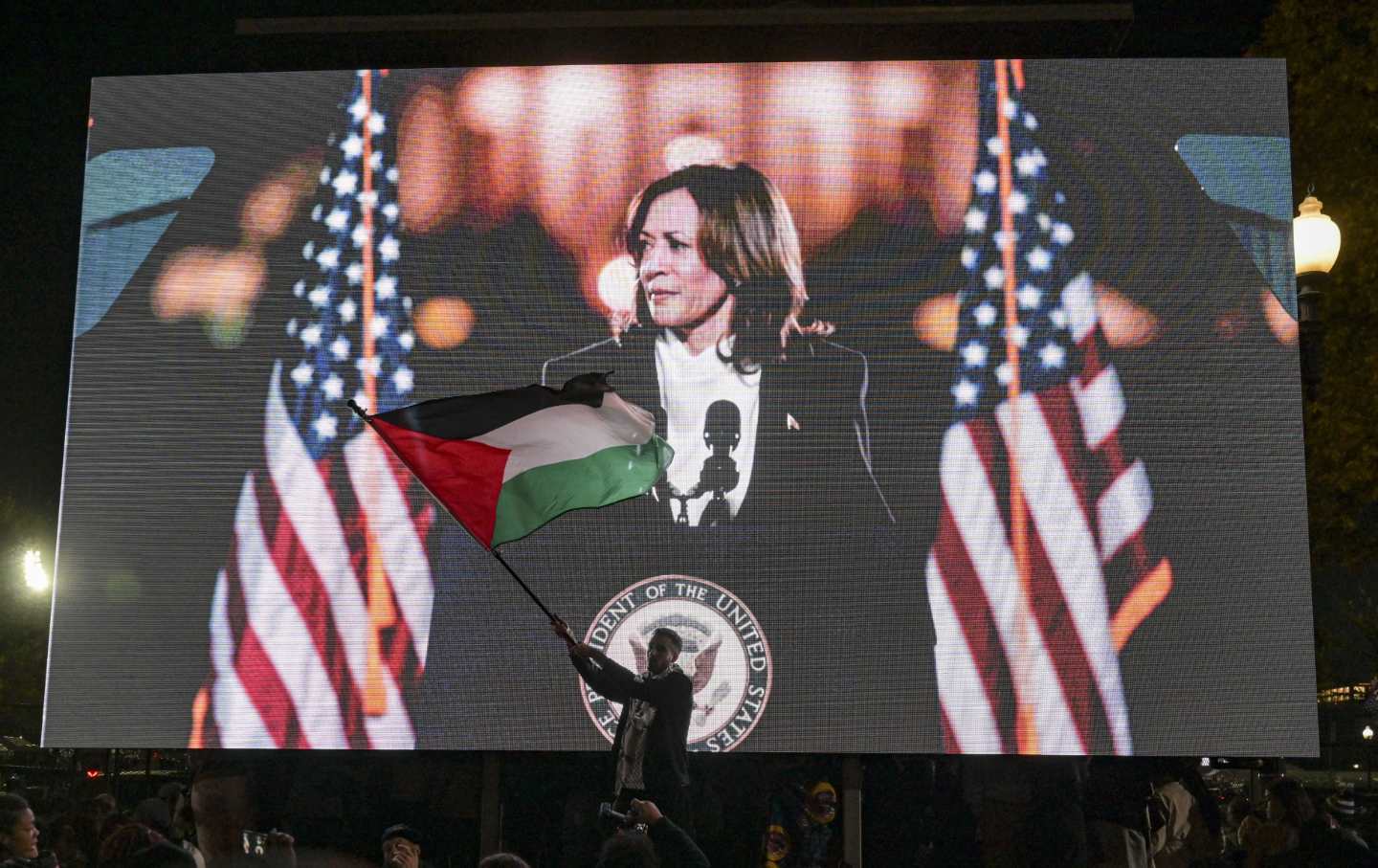

We now confront a second Trump presidency.

There’s not a moment to lose. We must harness our fears, our grief, and yes, our anger, to resist the dangerous policies Donald Trump will unleash on our country. We rededicate ourselves to our role as journalists and writers of principle and conscience.

Today, we also steel ourselves for the fight ahead. It will demand a fearless spirit, an informed mind, wise analysis, and humane resistance. We face the enactment of Project 2025, a far-right supreme court, political authoritarianism, increasing inequality and record homelessness, a looming climate crisis, and conflicts abroad. The Nation will expose and propose, nurture investigative reporting, and stand together as a community to keep hope and possibility alive. The Nation’s work will continue—as it has in good and not-so-good times—to develop alternative ideas and visions, to deepen our mission of truth-telling and deep reporting, and to further solidarity in a nation divided.

Armed with a remarkable 160 years of bold, independent journalism, our mandate today remains the same as when abolitionists first founded The Nation—to uphold the principles of democracy and freedom, serve as a beacon through the darkest days of resistance, and to envision and struggle for a brighter future.

The day is dark, the forces arrayed are tenacious, but as the late Nation editorial board member Toni Morrison wrote “No! This is precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.”

I urge you to stand with The Nation and donate today.

Onwards,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation