What Happened When a Palestinian Restaurant Hosted a Shabbos Dinner

A taste of what Palestine once was—and still could be.

Some people wore yarmulkes and some people wore keffiyehs and many people wore both. Neighbors broke bread—more specifically, a six-foot roll of challah—beneath a mural of the Al-Aqsa mosque, whose golden bricks were surrounded by a garland of olive branches.

It was a Friday night shabbos and over 1,300 people had crowded the new Ditmas Park branch of Ayat, a Palestinian restaurant chain with six locations across New York City and Pennsylvania. If Ayat sounds familiar, it’s either because you’re a Brooklynite with good taste in mashawy or because you’ve been reading some vitriolic headlines over the last month. (From ABC: “Palestinian-American business owners face death threats, negative reviews.” From the Daily Mail: “NYC Palestinian restaurant owner says he’s getting two death threats a MINUTE.”)

Many of the recent attacks on Ayat came from allies of Israel, who attacked the restaurant owners in the name of combating “Jew hatred.” But in the aftermath, both Jews and Palestinians came together to challenge this narrative and foster a unified front against anti-Palestinian violence—and it all happened over dinner.

The initial backlash happened after Elenani and Masoud promoted the December opening of their new location in a community Facebook group. Commenters pounced on the tongue-in-cheek title of their seafood menu, “From the river to the sea.”

The slogan, which had been on Ayat’s menu for almost a year, is regarded as a rallying cry for Palestinian liberation, but Zionist groups have labeled it “hate speech.” While the argument isn’t new, it’s taken on new life following Hamas’s October 7 attack against Israel and Israel’s subsequent assault on Gaza, which the International Court of Justice has dubbed a “plausible” genocide in the making.

The owners didn’t view the menu item as an attack against Jews but, rather, as a call for peace and equality in the Middle East. Masoud told The Nation it represented the version of Palestinian life she wanted the world to see: joy, generosity, and vibrant culture in the form of her family recipes, passed down through generations back in Jerusalem.

“If you approach a Palestinian person,” Masoud told The Nation, “they’re gonna welcome you into their home with open arms.… That was the message behind our first flagship location: ‘Hey guys, Palestinian identity is not this controversy.’”

That’s why, Elenani said, amid the bomb threats and media frenzy, he finally set in motion an idea he’d been dreaming of for a while now: a space that could bring Muslims and Jews together under one roof and, more specifically, at one dinner table.

“That’s why we’re here today,” he told The Nation on the night of the Shabbat.

The event was no small undertaking. Ayat shut down early on an otherwise bustling Friday night to prepare for the services at sundown and dinner at 9 pm. There was a tent for the Shabbat Torah reading, a klezmer band and trays of Levantine cuisine, including baba ganoush, rice, hummus, fattat jaj, and mansaf.

Elenani hired Jewish caterers, who provided the gargantuan challah as well as kosher food options. It was a challenge both logistically and politically; several kosher food providers, he said, had declined to serve the event. What’s more, Elenani estimated the night cost the small business owners upwards of $40,000; dinnergoers paid nothing.

The price was well worth it for Elenani. “If we’re able to utilize our cuisine and our kitchen to bring people together, I think that’ll always be the case, and we hope for it to stay as the case,” he said.

For many Jewish attendees, the dinner was more than just a call for peace; it was a call to action and a reassertion of a thriving Jewish culture of anti-occupation resistance. (Elenani did note, however, that “all are welcome” regardless of political beliefs.) As the daughter of a Holocaust survivor, 69-year-old Brooklynite Adele Rolider said she was thankful to be in a space where she could be proud of her Jewish heritage and exercise Jewish traditions of social justice. “I’m proud of being a daughter of survivors,” she told The Nation. “But what am I proud of? Am I proud of just one people having gone through this [so] that I can survive and grow?”

“My growth is to say ‘no’ to this,” she said of the ongoing Israeli violence against Palestinians.

It was a sentiment heard throughout the night, including and especially during the religious services. Jewish spiritual leaders with Kehilla, which is a loose collective of progressive Sephardic worshippers in New York City, began the night with a service that followed Sephardic and Mizrahi Jewish customs, which are those of the majority of Jews in Israel and the Middle East. During prayers, Jewish spiritual leaders led the crowd in a mourner’s kaddish, calling to mind the lives being lost today in Palestine and the lives lost many years ago in the Holocaust.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →If you stayed after the line that had formed around the block thinned and the six-foot challah hollowed; had you wandered upstairs at Ayat, where murals of Palestinian flags and folk dancers in keffiyehs surrounded Jewish worshippers swaying in song; if you had asked Laura Elkeslassy, a cantor who had assembled the siddur, or prayer book, for the night, about the melodic hymns she led from her seat at the table; if you listened to melodies that might have been sung by Jews in the Middle East and Palestine all those years ago, before the border walls and checkpoints were built, before the Nakba, you would have seen what much of Jewish life was like then or could be like now.

“The stories of Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews are often erased,” Elkeslassy told The Nation. “Centuries of French and British colonialism created a separation, but that’s not the way they were living for millennia. Tonight, we wanted to recreate these ancient bonds between our communities.”

Perhaps the most literal expression of these connections were the songs, hand-selected for this night by Elkeslassy herself. They were largely works of contrafact, which are prayers or poems sung to the tune of borrowed melodies from another language. One might hear “Li Habibi” (“For My Beloved”), for example, a classical Andalusian song derived from the Arabic “Nuba Hijaz el Kbir” and its Hebrew counterpart “Elohim diber bekodsho.”

“The theology of Zion returned and the Torah pre-dates the nationalist movement of Zionism, and those who read Torah know it does not need to translate that way,” Elkeslassy said. “This book shows a vision of abundance, peace, and eternal justice.”

The night conjured stories from a time before the Israeli state when pockets of multifaith communities lived, worked, and dined together in Palestine, as historian Menachem Klein documents in his book Lives in Common: Arabs and Jews in Jerusalem, Jaffa and Hebron. Jews and Muslims alike founded businesses and public service projects together, such as the Red Crescent, established in Jerusalem in 1916. Jewish and Muslim mothers nursed each other’s babies or watched over each other’s children. Cultural conflict and violence still existed, of course, but in each other, many Jews and Muslims found camaraderie, and a local, unifying identity: Palestinian.

“It did not arrive from the outside, like Arab nationalism and Zionism,” Klein writes, “but grew out of the daily lives of the country’s inhabitants.”

It’s a sentiment Elkeslassy echoed. “Tonight’s event brought hope,” she said. “If the leaders can’t deal with this, then maybe the people will.”

We cannot back down

We now confront a second Trump presidency.

There’s not a moment to lose. We must harness our fears, our grief, and yes, our anger, to resist the dangerous policies Donald Trump will unleash on our country. We rededicate ourselves to our role as journalists and writers of principle and conscience.

Today, we also steel ourselves for the fight ahead. It will demand a fearless spirit, an informed mind, wise analysis, and humane resistance. We face the enactment of Project 2025, a far-right supreme court, political authoritarianism, increasing inequality and record homelessness, a looming climate crisis, and conflicts abroad. The Nation will expose and propose, nurture investigative reporting, and stand together as a community to keep hope and possibility alive. The Nation’s work will continue—as it has in good and not-so-good times—to develop alternative ideas and visions, to deepen our mission of truth-telling and deep reporting, and to further solidarity in a nation divided.

Armed with a remarkable 160 years of bold, independent journalism, our mandate today remains the same as when abolitionists first founded The Nation—to uphold the principles of democracy and freedom, serve as a beacon through the darkest days of resistance, and to envision and struggle for a brighter future.

The day is dark, the forces arrayed are tenacious, but as the late Nation editorial board member Toni Morrison wrote “No! This is precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.”

I urge you to stand with The Nation and donate today.

Onwards,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

When It Comes to Public Health, We Need to Tap Into People, Not Pundits When It Comes to Public Health, We Need to Tap Into People, Not Pundits

The future of our health under Trump is going to be bleak. But the solution lies in our communities, not individual personalities.

Mr. Scarborough Goes to Mar-a-Lago Mr. Scarborough Goes to Mar-a-Lago

The hosts of Joe Biden’s favorite political talk show have quickly pivoted to kissing the ring of the incoming president.

Watching a Parallel Media Try to Make Trump the Big Sports Story Watching a Parallel Media Try to Make Trump the Big Sports Story

The president-elect did not dominate the world of sports this weekend, but Fox News and Internet tabloids are inventing new realities.

The First Amendment Will Suffer Under Trump The First Amendment Will Suffer Under Trump

Given what’s heading our way, we need a capacious view and robust defense of the First Amendment from all quarters.

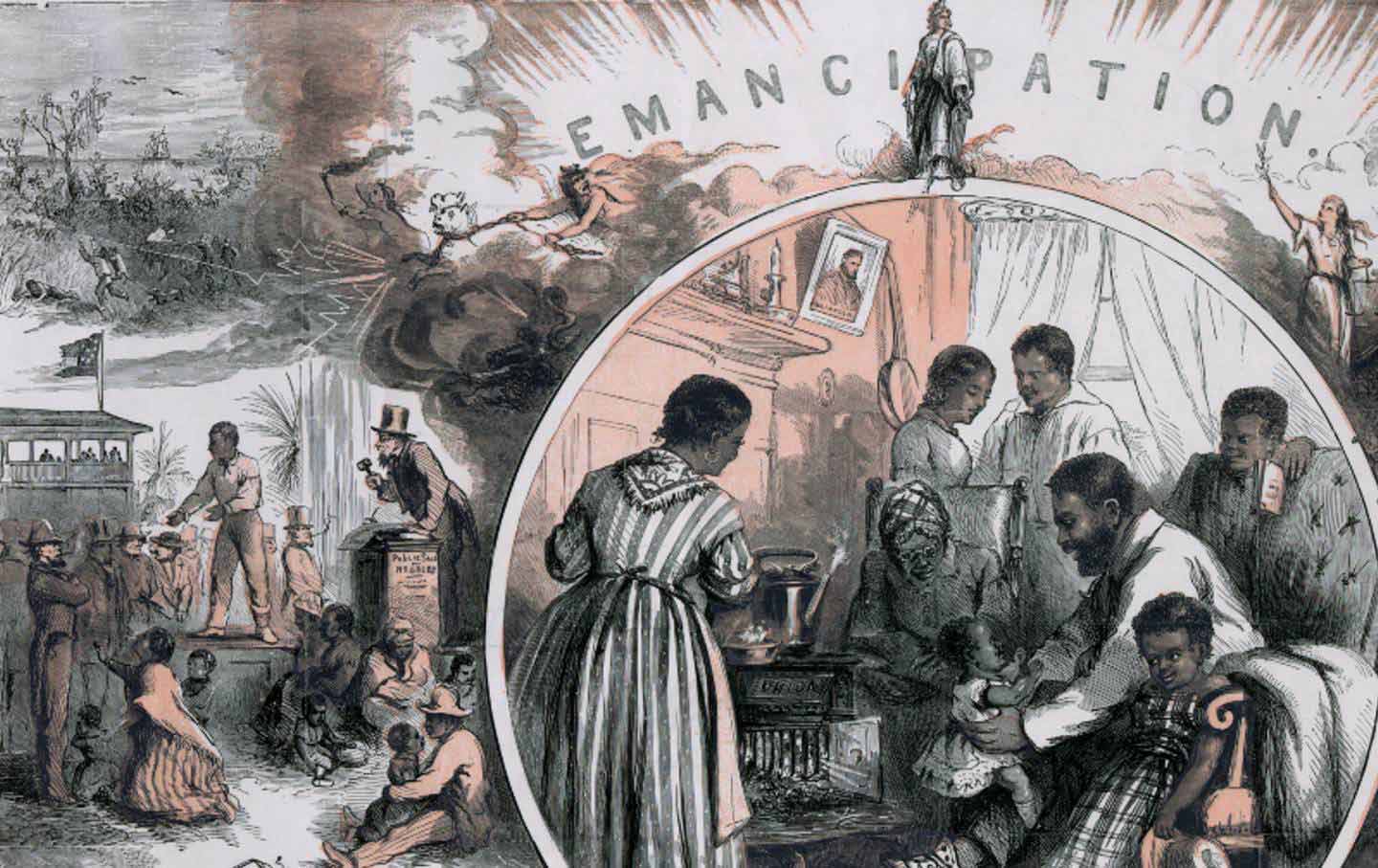

Slavery in an Age of Emancipation Slavery in an Age of Emancipation

Robin Blackburn’s sweeping history of slavery and freedom in the 19th century.

How Wisconsin Lost Control of the Strange Disease Killing Its Deer How Wisconsin Lost Control of the Strange Disease Killing Its Deer

Despite early containment efforts, chronic wasting disease has been allowed to run rampant in the state. That’s bad news for all of us.