Biden Is Repeating Bush’s Post-9/11 Playbook. It’s Not Working.

Just like his predecessor, the president is decrying anti-Arab and Muslim hatred while helping to fuel it. But people are refusing to let him get away with this hypocrisy.

Hajur El-Haggan had been teaching at Argyle Middle School in Silver Spring, Md., for five years when the Israel-Gaza war began. She had never been shy about her views, often wearing T-shirts, pins, and even fingernail art with slogans expressing solidarity with Palestine. No one had ever made an issue of her politics in the classroom.

Then, in late November, El-Haggan was put on leave by the Montgomery County Board of Education because she had added a popular call for Palestinian liberation, “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free,” to her e-mail signature. (Her attorney, Rawda Fawaz, says that quotes in e-mail signatures are technically against the county’s rules, but this policy was applied only to speech related to Palestine.)

El-Haggan is suing the school board for discrimination with the help of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, along with two other teachers who say they were also suspended by the district for their Palestine advocacy. Days before being put on leave, El-Haggan also had a Palestinian flag ripped off her car in the school parking lot.

As a Muslim of Egyptian and Sudanese descent, El-Haggan was brought up with stories of how Islamophobia affected her older family members in the early 2000s. For El-Haggan, and so many others, the current climate has disturbing parallels to the outbreak of bigotry experienced by Arabs and Muslims after the September 11 attacks. CAIR has received over 3,000 complaints of Islamophobia and anti-Arab bias and discrimination since the October 7 Hamas attacks, many related to employment and education like El-Haggan’s.

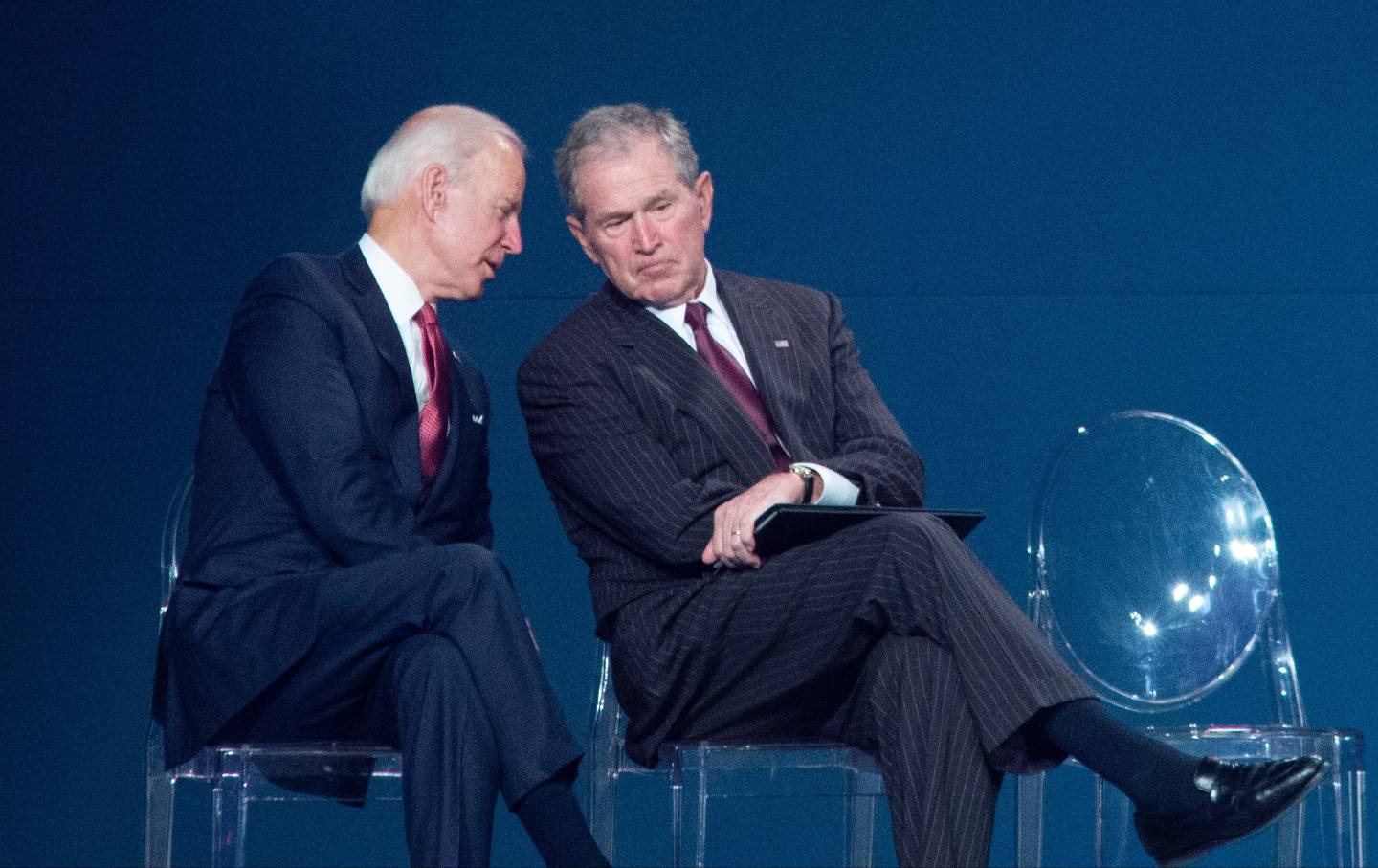

This parallel is not a coincidence, but rather a result of the policies and strategies of the people in charge of the country—from George W. Bush then to Joe Biden now. And both men responded to this spread of hatred with the same pandering hypocrisy.

Bush condemned Islamophobia and anti-Arab hate while fueling mass violence against Muslims and Arabs at home and abroad. Similarly, Joe Biden has wanly attempted to present himself as an ally of Muslim and Arab Americans, while creating the perfect conditions for hate against this community to thrive. (Israel has killed over 29,000 Palestinians, mostly women and children, in its ongoing bombardment of Gaza, with the Biden administration’s total financial and diplomatic support.)

“When you see that the government is protecting one class of people and not others that are also impacted, then society will mimic that and cast out one group—Muslims and Arabs—while being accommodating of another,” said El-Haggan.

But while Bush paid a relatively small political price for stoking racism and Islamophobia, Biden now finds himself facing striking levels of resistance from a conscious public.

Following the attacks on the Twin Towers, Bush announced a costly and lengthy war that would make no distinction between “terrorists who committed these acts and those who harbor them,” launching air strikes against the Taliban and Al Qaeda in Afghanistan and beginning the so-called War on Terror, which would only expand over the next few years.

Bush adopted a strategy of preemptive war, justifying the invasion of Iraq by falsified claims that Saddam Hussein was storing weapons of mass destruction. As the powerful chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Biden voted for the authorization of military force in Iraq, stating in Congress in 2002, “Saddam [Hussein] has got to go, and it is likely to be required to have U.S. force to have him go, and the question is how to do it in my view, not if to do it.”

Later that year, Benjamin Netanyahu, after serving his first tenure as the prime minister of Israel, testified before Congress in support o the Iraq invasion. He stated that the most important thing in winning the War on Terror was “the application of power.”

“It’s not a question of whether Iraq’s regime should be taken out, but when should it be taken out,” Netanyahu said, echoing the imperialist rhetoric of both Biden and Bush. In Iraq alone, the war left roughly 1 million dead, up to 2 million widowed, and 5 million children orphaned.

Back at home, hate crimes and discrimination targeting Muslims and those racially profiled as Muslim were increasing to unprecedented levels. Bush expressed his dedication to vengeance and targeting “terror” wherever it existed, allowing the vague target to be placed on anyone the public deemed a threat.

The Bush administration launched an extensive surveillance project on the Muslim community—monitoring not only political activity but also schools, mosques, and even charities. Globally, more than 100,000 Muslims were detained, many held indefinitely and in secret locations.

But even as he pushed destructive wars and discriminatory policies, Bush rhetorically positioned himself in opposition to bigotry against Muslims and Arabs. He even famously visited the Islamic Center of Washington, D.C., a week after 9/11, addressing the crowd with quotes from the Koran and saying, “The face of terror is not the true faith of Islam. That’s not what Islam is all about. Islam is peace.” (Pundits have been praising him for those words ever since, even though they had little to do with his actions.)

The response to 9/11 also created a new identity among many Muslim and Arab Americans. What was once a large yet often unnoticed community became hyper-visible, and therefore more vulnerable to scrutiny. As Moustafa Bayoumi put it, “Muslim Americans were not just racialized after 9/11; we were invented. The term barely existed in the popular imagination before 2001.” Many Muslim Americans practiced policing themselves in a desperate effort to appear patriotic and “moderate.”

Organizations were coping with increased visibility through efforts to educate Americans about Islam, highlighting it as a tolerant religion compatible with American values. In 2004, CAIR released a TV and radio campaign featuring the slogan “I am Muslim, I am American,” as well as an online petition called “Not in the name of Islam” to denounce acts of terror. The campaign featured images of Muslim Americans as police officers, human rights activists, and Little League baseball players. There was, of course, widespread resistance against the War on Terror, creating some of the largest protests the world has seen. However, many Muslim Americans remained on the defense, often distancing themselves from political issues and foreign policy decisions as a form of survival.

After October 7, Biden, like Bush, initially ramped up his condemnation of attacks on Muslims and Arabs on American soil. When 6-year-old Palestinian American Wadea Al-Fayoume was stabbed 26 times in October, the White House was quick to release a statement condemning the murder. It also announced a Strategy to Counter Islamophobia.

Since then, Biden has grown more silent, even as both domestic hate and offshore war crimes continued. In November, three Palestinian American college students were shot while wearing traditional Palestinian keffiyeh scarves and speaking Arabic. Biden did not go beyond offering vague condolences to their families.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →One of the survivors of the Burlington shooting, Hisham Awartani, became partially paralyzed by the shooting and used the opportunity to redirect people’s attention toward those killed in Gaza. “I take solace in the fact that I am able to receive this care…. it makes me think of people in Gaza…who have been disabled by bombing,” he said in one interview.

While the administration sympathized with Awartani as a victim of a freak attack, his status as a critic of state-sanctioned violence abroad—and as a symbol of the dangers that such violence causes on the domestic front—was ignored.

On February 4, a 23-year-old Palestinian American was stabbed in Austin, Tex., after attending a rally calling for a cease-fire. The White House has not commented. The stabbing victim blamed Biden for the assault.

Meanwhile, Biden continued to show the shallowness of his concerns for Palestinians, even on the rhetorical level. In a statement marking 100 days of war, Biden honored the hostages taken by Hamas, with no mention of the countless Palestinians, including American citizens, killed and held captive by Israel. As Awartani and others have made clear, it can no longer be acceptable for politicians to coddle survivors of hate crimes without acknowledging their anti-Muslim and anti-Arab foreign policy.

The déjà-vu feeling of Biden’s policies has created a shift in organizing among Muslim and Arab Americans, on both the individual and organizational level. As a nonprofit, CAIR can’t endorse political candidates, but it has been regularly publishing statements criticizing the Biden administration’s war on Gaza. At the March on Washington on January 13, Executive Director Nihad Awad announced the creation of a CAIR Political Action Committee. Fawaz explained that the group’s priority moving forward is in “unlocking Muslim potential” and protecting the rights of Muslim advocates at protests, workplaces, and schools without having to compromise their values.

Action is connected to identity, argues Dr. Hajar Yazdiha, a scholar at the University of Southern California. Yazdiha found in a study that Muslim Americans who viewed themselves as aspirationally “white” had more of a desire to assimilate and be model citizens. Those who accepted that they would always be seen as “outsiders,” despite their best efforts, were more likely to be critical of the systems they lived under and to positively view solidarity with other communities of color.

“These are second-generation and third-generation Muslim immigrants, who have grown up alongside Black and brown classmates. They’ve learned the histories of the civil rights struggle, and so they’re contextualized in their own experiences within this longer history,” said Yazdiha “It’s easier for them to understand that their experiences are not unique, and they’re actually part of the American imperial project.”

Muslim and Arab Americans are experiencing a clarity gained only through hindsight: The people that those in their community helped elect (Bush received 78 percent of the Muslim vote in 2000) have long worked to dehumanize them. Standing unified against efforts to destroy the life, culture, and history of Arab and Muslim nations, this particular moment opens up a unique opportunity of influence for those in their diasporas.

Biden has sensed this. After The Wall Street Journal published an op-ed that called Dearborn, Mich., home to a large Muslim and Arab community, “America’s jihad capital,” which prompted increased security at places of worship across the city, Biden said, “Americans know that blaming a group of people based on the words of a small few is wrong. That’s exactly what can lead to Islamophobia and anti-Arab hate, and it shouldn’t happen to the residents of Dearborn—or any American town.”

But he is finding that Arabs and Muslims are refusing to be quite as accommodating as he’d like. Leaders in Dearborn are encouraging voters to select “uncommitted” in Michigan’s upcoming primary in protest of his unwavering support for Israel. As gruesome images of the Biden-approved Israeli assault on Gaza continue to spread online—a doctor amputating his niece’s leg on a kitchen table without anesthesia, a young girls eyes blackened with blood after an Israeli tank drove over her tent, killing her father and sister, a 6-year-old trapped in a car with dead family members before also being killed by Israeli gunfire—any disappointment and grief directed toward Biden has already solidified into collective resistance.

Zaid El Baroudi, a half-Palestinian and half-Egyptian student at North Carolina Central University and cofounder of a MAS-PACE chapter in Raleigh, has been helping young Muslims in his community organize around Palestine. “For so long, Muslims in America felt very powerless. They have pressure from within their community not to engage in the American political system, which I think is a massive mistake,” said El Baroudi, who has noticed an increase in motivation among the youth he works with, noting an especially passionate 16-year-old who spoke at a recent city council meeting. But one piece is still missing. “Our biggest problem is that Muslims don’t vote, [politicians] don’t care because you don’t vote. You don’t matter.”

An estimated 35,000 people in the Research Triangle are Muslim, an area made up of three of the most populous cities in North Carolina, which, like Michigan, is a swing state, and carries a strong potential to influence the upcoming election. “The Muslim community alone has the power to swing this either left or right,” El Baroudi said. “And I think that when people realize that power and mobilize, we can have a lot more power over local government.”

It seems difficult to imagine these kinds of statements being made in the era of Bush. He faced Muslim and Arab communities that were relatively politically passive, to the point where he felt he could ignore their demands for civil rights and justice. But Biden, despite his attempts to repeat the Bush playbook, is not so lucky. After years of experiencing Bush’s brutal wars, discriminatory policies stretching over decades, and continual exclusion despite “following all the rules,” many Muslim and Arab Americans are in no mood to give the president a pass.

Instead, they have adopted a different way of understanding their place within the United States, and politicians are now feeling the repercussions. “Folks will not fall in line like they had before,” said Yazdiha. “They will not look for the lesser of two evils, because they are realizing that both evils are equally detrimental to their existence.”

We cannot back down

We now confront a second Trump presidency.

There’s not a moment to lose. We must harness our fears, our grief, and yes, our anger, to resist the dangerous policies Donald Trump will unleash on our country. We rededicate ourselves to our role as journalists and writers of principle and conscience.

Today, we also steel ourselves for the fight ahead. It will demand a fearless spirit, an informed mind, wise analysis, and humane resistance. We face the enactment of Project 2025, a far-right supreme court, political authoritarianism, increasing inequality and record homelessness, a looming climate crisis, and conflicts abroad. The Nation will expose and propose, nurture investigative reporting, and stand together as a community to keep hope and possibility alive. The Nation’s work will continue—as it has in good and not-so-good times—to develop alternative ideas and visions, to deepen our mission of truth-telling and deep reporting, and to further solidarity in a nation divided.

Armed with a remarkable 160 years of bold, independent journalism, our mandate today remains the same as when abolitionists first founded The Nation—to uphold the principles of democracy and freedom, serve as a beacon through the darkest days of resistance, and to envision and struggle for a brighter future.

The day is dark, the forces arrayed are tenacious, but as the late Nation editorial board member Toni Morrison wrote “No! This is precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.”

I urge you to stand with The Nation and donate today.

Onwards,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

BREAKING: Matt Gaetz Quits and Journalism Still Matters—a Lot BREAKING: Matt Gaetz Quits and Journalism Still Matters—a Lot

Forty-five minutes after CNN contacted Trump’s attorney general nominee about additional allegations of sexual misconduct, he was done.

The Red Wave Didn’t Hit Statehouses in This Election The Red Wave Didn’t Hit Statehouses in This Election

State-level Democrats largely held their ground, even scoring key victories in battleground states—and under Trump, that’s going to matter.

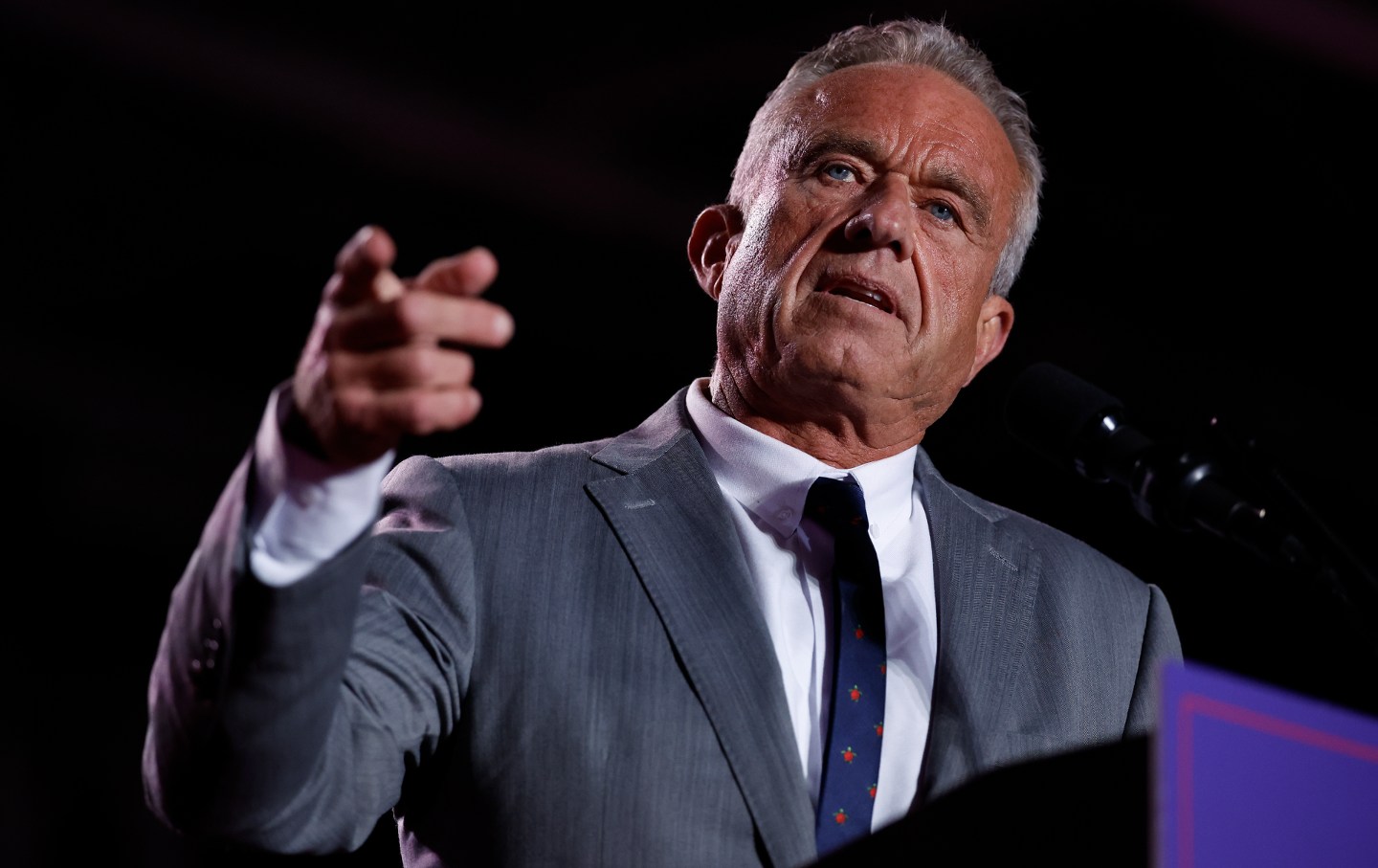

How Nominally Pro-Choice RFK Jr. Can Get Anti-Abortion Groups to Back His HHS Nomination How Nominally Pro-Choice RFK Jr. Can Get Anti-Abortion Groups to Back His HHS Nomination

He can pick a strident abortion opponent like Roger Severino, who wrote the Project 2025 chapter on HHS, as his number two.

Red Flags Red Flags

The result of the presidential election reflects individual and collective responsibility.

How Loyalty Trumps Qualification in Trump Universe How Loyalty Trumps Qualification in Trump Universe

Meet “first buddy” Elon Musk.

Bury the #Resistance, Once and For All Bury the #Resistance, Once and For All

It had a bad run, and now it’s over. Let’s move on and find a new way to fight the right.