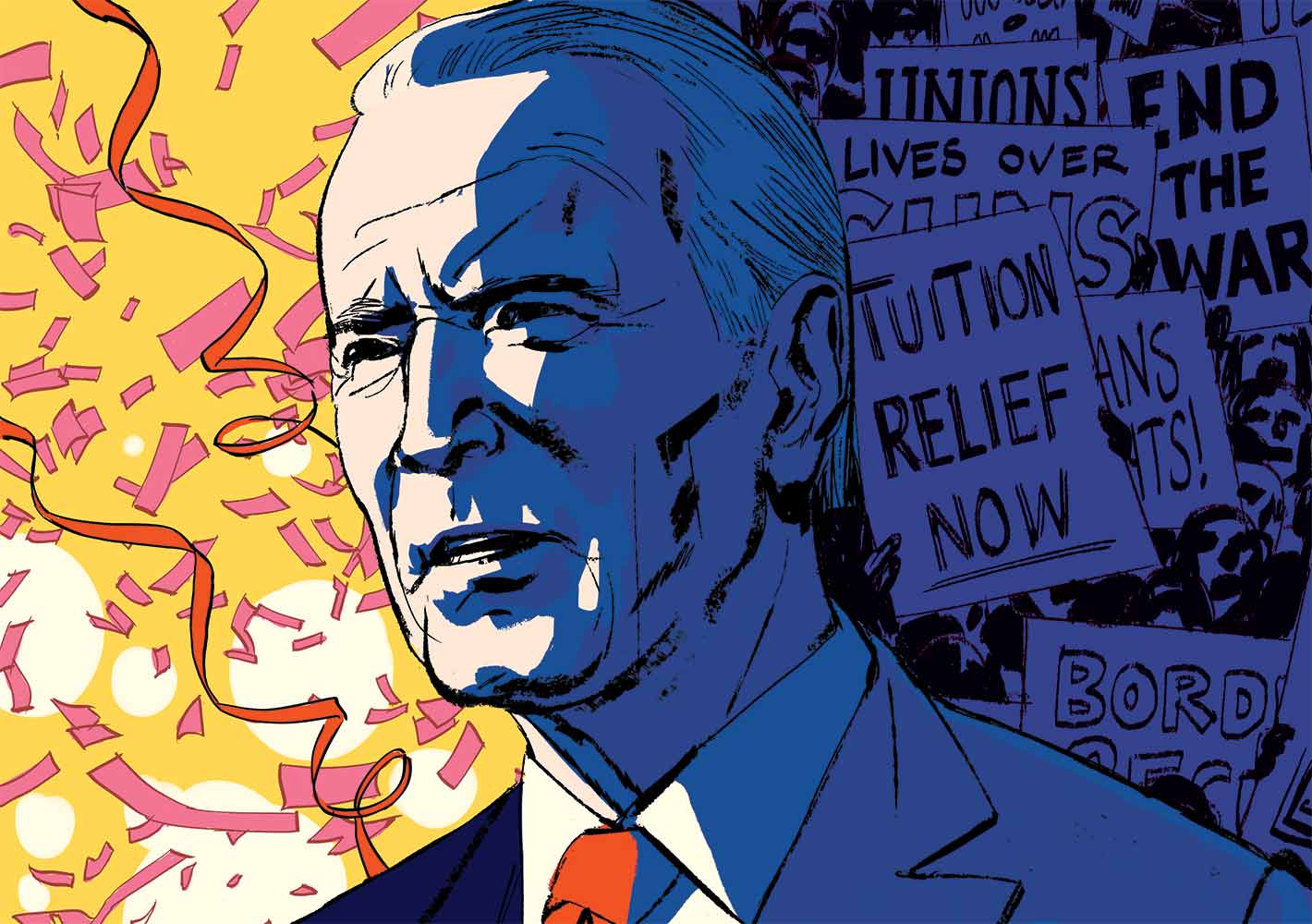

The Divided President

Who is in charge in the Biden White House?

Who Is In Charge in the Biden White House?

In The Last Politician, Franklin Foer offers a portrait of an administration at odds with itself.

Beneath Joe Biden’s avuncular, aw-shucks demeanor lies an ego even larger than his mouth. Three presidential campaigns across three separate decades say everything one needs to know about the man’s sense of himself and his role in history. And it must come as some relief to Biden that history still has a role for him. The Cold War that shaped American politics for most of his career has given way not to an age of international peace and untroubled prosperity but to an era of political and economic upheaval in which his can-do optimism is still very much in demand. Or, at least, this is what he and his boosters assure us. The institutions of American democracy are still worthy of our faith; what we need is the right person with the right intentions at their helm.

Books in review

The Last Politican: Inside Joe Biden’s White House and the Struggle for America’s Future

Buy this bookTo the surprise of many, Biden and the Democrats in Washington have managed to pull some real and even transformative policy victories out of those sclerotic institutions over the course of his term so far. He signed the Inflation Reduction Act, the nation’s first major climate bill, into law. Together with the CHIPS and Science Act and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, Bidenomics—the White House’s label for its industrial programs—has reasserted the federal government’s role in driving economic investment. There have been less heralded victories, like the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, the first major gun control legislation to be passed by Congress in nearly 30 years. And Biden has also used the powers of his office to push a pro-labor, pro-competition agenda through the executive agencies.

Nevertheless, Biden is entering his reelection campaign as a weak and embattled incumbent. Voters remain deeply pessimistic about an economy that, by conventional measures, has actually improved under his watch. Biden’s age now weighs heavily on the public’s mind. And the administration’s response to the crisis in Gaza has cratered Biden’s standing with progressives, including those who cheered the withdrawal from Afghanistan not so long ago. That fulfilled promise and the investments of Bidenomics seemed, for a time, to quell the impatience over all that the Democrats have left undone on key issues, from immigration to democratic reform. Gaza has changed all that. While the press might have welcomed Biden into the White House with comparisons to Franklin Roosevelt—comparisons that Biden encouraged—he now finds himself dogged by less flattering comparisons to Lyndon Johnson, whose grand domestic policy agenda ended up being overshadowed by the blood that he allowed to be cruelly and uselessly shed in Vietnam.

Presidential historians looking back at the past few years will document Biden’s failures in greater detail than we can now, of course, but they’ll also take care to note, if they’re any good, that even the best presidents and most capable administrations find themselves buffeted and dazed by forces and events outside their control. The competence and character of well-placed individuals, as Biden and his backers insist, really do matter. But structural conditions and the movements shifting politics outside the White House always matter too. Though Biden may have insisted at the outset of his presidency “that he would prove that democracy could still deliver for its citizens, that it hadn’t lost its capacity to accomplish big things,” as Franklin Foer writes in The Last Politician, his new book on the first two years of the Biden administration, his successes on that score have been more the product of a sea change in Democratic politics than his own leadership. And his odds of keeping the presidency might rest on whether he comes to recognize that.

In Foer’s view, many of Biden’s achievements can be credited to his personality and character: He’s a skilled and uncommonly sensitive statesman, possessed of all the dealmaking acumen that Donald Trump so often boasted about and so obviously lacked. “As I reported on him at close distance,” Foer writes, “my respect for him grew. I came to appreciate his ability to shelve his ego and empathetically understand the psychology of the foreign leaders he sparred with and the senators he wooed.”

But strangely, one comes away from Foer’s closely observed account of the Biden White House with the impression that Biden’s successes have often been achieved in spite of an evidently fickle and mercurial temperament. Biden “deeply craves advice,” Foer tells us, “but is often stubbornly resistant to it.” On foreign policy, he is guided by a “swaggering sense of his own wisdom” and a contempt for “the mandarins” of the foreign-policy Blob “trying to muddy things up with their abstractions and theories.” While we’re told that Biden resents “the presence of trust-fund kids who showed up in Washington as interns,” he nevertheless takes pride in his staff of Ivy Leaguers, whom he introduces to visitors as “his meritocratic trophies.”

In the Joe Biden that Foer gives us, we have yet another president—the third in this young century—who seems to act substantially from the gut. And while that’s worked out well for progressives here and there, Biden’s personality and conservative instincts have also been obstacles for leftward progress.

During the 2020 campaign, for instance, he repeatedly promised to lift the cap on refugees imposed during the Trump administration, a pledge that was directly reaffirmed to Congress in February 2021, even as the swelling number of unaccompanied minors arriving at the border began drawing public attention and criticism. “It was an important symbolic reversal,” Foer writes. “And all that it required was Biden signing paperwork approving the funding for it. But in a cantankerous mood when considering it, he doubted whether he should. In an early March meeting that included Secretary of State Antony Blinken, he nodded in the direction of his longtime adviser, a passionate proponent of raising the cap. ‘They want me to increase the number of people in the country, but that’s kind of crazy.’”

After the White House announced in April that Biden would be reneging on his promise and leaving Trump’s cap in place for at least the year ahead, staffers including chief of staff Ron Klain and Domestic Policy Council director Susan Rice embarked on a plan to gently nudge the president back to his original position, an effort that involved managing Biden’s temper. “It was perfectly clear that Biden would keep raising the subject himself, usually in meetings about the border crisis, usually with an edge of aggression,” Foer tells us. “He moaned, ‘Can you believe that they want me to go back to those high numbers?’ At a moment like that Susan Rice would shoot a glance across the room, which told aides, ‘Don’t take the bait.’”

Eventually, the improvement of conditions at the border created an opening for a more forceful push. Biden staffer Amy Pope was sent to a weekly meeting on the border with the paperwork for lifting the refugee cap in hand. Trying to seal the deal, Pope observed that by raising the refugee cap, Biden could help secure his legacy. Foer tells us that this line set Biden off. “‘I don’t care about my legacy,’ he shot back. In the moment, Biden’s logic shifted. All he cared about, he said, was treating the refugees humanely.” Without much further ado, he signed the document on the spot.

Anecdotes like this undermine Foer’s praise for Biden’s personal and political acumen a fair bit. The president is a rather insecure man; he needs to be constantly prodded and managed by those around him in ways that flatter his ego. In March 2022, when Biden paid a visit to Poland, he gave a speech that ended with a shocking bit of improvisation. “For God’s sake,” he thundered of Vladimir Putin, “this man cannot remain in power.” That impromptu call for what sounded like regime change in Russia was immediately walked back by his aides, and it left Biden feeling even more surly. “Rather than owning his failure, he fumed to his friends about how he was treated like a toddler,” Foer writes. “Was John Kennedy ever babied like that?” Joe’s no Jack Kennedy, but as the remark suggests, he’s spent a lifetime working to become a figure of Kennedy’s stature.

“As a young senator,” Foer notes, “he gave rousing addresses that aspired to the lyricism of the Kennedys, rife with verbal pyrotechnics, moments of soaring eloquence. They seemed a source of pride for him, evidence of how he mastered public speaking, the very thing that had once debilitated him.” And the Poland speech, in Biden’s view, was an increasingly rare opportunity to prove that he could speak as movingly and memorably as JFK did—by way of “a grand exhortation about the moral imperative of thwarting authoritarianism.”

That grasping ambition is a critical part of who Biden is. He has always been a poor fit within the Democratic establishment he now commands. As he’s fond of reminding us, he really did grow up in a middle-class family from Scranton, Pa. He didn’t go to an Ivy League college. He was among the least affluent members of the Senate. And by his own admission, he’s a gaffe machine with a gift for saying the wrong thing at the wrong time.

Even after an uncommonly hefty vice presidency in which Biden took up, among other responsibilities, ending the war in Iraq and overseeing the implementation of the 2009 Recovery Act, he had to suffer the indignity of being shooed away from the 2016 race and was openly discouraged by party elites, including Barack Obama himself, from running yet again in 2020. Biden entered the race anyway, but even then he appeared hopelessly out of step with a party being pulled to the left, winning the nomination only after Democratic leaders and his opponents belatedly closed ranks behind him in order to thwart the advance of Bernie Sanders.

The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and the potential scale of the response it so obviously demanded did ultimately put Biden into more accord with progressives. And the refugee-cap episode and other moments in Foer’s book suggest that Biden can be tugged left, on occasion, by his advisers. But that only goes to show, as Foer’s account inadvertently makes clear, that the administration’s sprawling cast of supporting characters—including an inner circle of staffers (most of whom, ironically, are not committed progressives)—are perhaps more responsible for the progressive tilt of the administration than Biden himself is.

The Last Politician may be readers’ introduction to many of these staffers. We meet Biden’s unfussy and unpretentious speechwriter, Mike Donilon—“the closest thing the president has to an alter ego,” Foer writes—who shifts from feeding Biden the gospel of national unity to pushing for a more aggressive tone against Trump and Republican extremism and who tries, albeit with mixed success initially, to have Biden voice more outrage in the wake of the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision.

We also meet White House deputy chief of staff Bruce Reed, a former head of the centrist Democratic Leadership Council, whose appointment was castigated by progressives—though when we’re introduced to him in The Last Politician, Reed is cultivating Biden’s interest in corporate concentration and monopoly power, which leads to the appointment of two antitrust crusaders: Lina Khan to head the Federal Trade Commission and Tim Wu to a position in the White House.

Of those closest to Biden, Ron Klain—who was White House chief of staff until last February and has worked for Biden on and off since young adulthood—has been particularly instrumental in pulling Biden in a more progressive direction, having moved left himself during Trump’s term. As Foer notes of Klain: “Over the [2020] campaign, he had formed an easy relationship with Bernie Sanders, who appreciated how quickly he responded to his calls and how he seemed open to suggestions. With appointments to administration jobs, he helped Elizabeth Warren place her protégés in top posts. He said explicitly that he wanted to avoid fights with the Left, on the cusp of a moment when the administration would need its support.”

While Donilon and Reed encouraged Biden to continue building support for his legislative agenda among moderate Republicans in the Senate, Klain—who had seen firsthand the Obama White House’s fruitless efforts to do likewise with the Affordable Care Act as Biden’s chief of staff at the time—urged Biden to take advantage of the Democrats’ narrow Senate majority and the budget reconciliation process to pass the American Rescue Plan.

Outside of this trio, whose members have known Biden and one another for around 40 years—“Ron Klain was the godfather of Reed’s child,” Foer observes at one point, and “Donilon and Klain went to Georgetown together, where Klain covered Donilon’s bid to become student body president in the student newspaper” —one other figure has had a particularly significant influence on the direction Biden has taken as president, despite having spent only about a decade or so in his orbit: Jake Sullivan.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Formally the national security adviser, Sullivan was also “the primary architect of the Biden domestic policy agenda,” Foer tells us, having pieced together the platform that would become known as “Build Back Better” while he worked on the Biden campaign. Sullivan came to that campaign as a scarred veteran of Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential run—in 2015, she had assigned him the task of figuring out what progressives were all riled up about in anticipation of a campaign against Elizabeth Warren.

Nothing in Sullivan’s résumé suggested that he’d be particularly well-suited to this task. A Yale graduate and Rhodes Scholar who had found his way to Clinton’s side not long after finishing law school and then followed her into the Obama administration, Sullivan was elite Washington personified. Nevertheless, as he would eventually report back to Clinton, the critiques that Warren, Sanders, and progressive activists in the years after Occupy Wall Street were leveling at the Democratic establishment were too disquieting and too persuasive to be brushed aside. “While he wasn’t prepared to propose that Hillary Clinton adopt Elizabeth Warren’s policies, he pushed in that direction,” Foer writes. “On the whiteboard in his office during the Clinton campaign, he scrawled the word rents and left it there as a token of his growing hostility to monopoly.”

Whatever interest Clinton might have had in crafting a more progressive policy agenda evaporated with Trump’s nomination and the subsequent shift in the focus of the race. But Sullivan’s interest in that project survived the campaign and only deepened over the course of Trump’s term, which provoked soul-searching across the Democratic policy world, particularly among the party’s young professionals. “They didn’t just worry about Trump,” Foer writes. “They fretted about what would become of the Democratic Party. It seemed as though the party was fracturing, just like the nation.” And while some party leaders responded to that fracturing by continuing the time-honored tradition of angrily punching left, Sullivan and other like-minded aides went out of their way to hear the progressives out.

“One of Sullivan’s close collaborators on the Clinton campaign, Heather Boushey, organized a reconciliation tour,” Foer explains. “Along with Mike Pyle, who left the Obama White House to work in finance, she put together a series of dinners in Washington, New York, and San Francisco. Young establishment wonks broke bread with Elizabeth Warren disciples, labor union officials, and intellectuals from left-leaning think tanks. At these meals, the establishment found itself gravitating towards an alliance—or rather a confluence.”

That confluence would be reflected in Sullivan’s work patching together the Build Back Better agenda. And when one factors in everything that’s fallen under his purview in his official capacity as national security adviser—including his leading role in managing the withdrawal from Afghanistan—it begins to seem like we’ve been living these past three years under a Sullivan administration as much as a Biden one.

On the whole, Foer holds the Biden administration in high esteem, though he qualifies his enthusiasm when it comes to the withdrawal from Afghanistan—less irresponsibly managed than rushed, in his view—which he details in a lengthy, day-by-day account that takes up a substantial portion of his book’s middle section.

But even there, he finds things to admire. The rapid creation and management of a network of camps for Afghan refugees across Europe, he writes, required “a massive amount of quick diplomacy and logistical know-how,” and the administration’s officials rose to the challenge. “In the end, the US government housed sixty thousand Afghans in facilities, many of which didn’t exist before the fall of Kabul,” he notes. “It flew 387 sorties from [Kabul’s airport]. At the height of the operation, an aircraft took off every forty-five minutes. It was a terrible failure of planning that necessitated a mad scramble—a mad scramble that was an impressive display of creative determination.”

He assesses the administration’s early response to Covid similarly: The task of cleaning up Trump’s mess fell to a slate of officials that Foer introduces to us as an Avengers-style team of super-technocrats. “From all his years responding to once-in-a-century storms and toxic spills,” Foer writes, Covid supply coordinator Tim Manning, a former deputy administrator at the Federal Emergency Management Agency, “had learned how to make things happen in cramped conditions, how to move fleets of utility repair trucks across the nation overnight, and how to find housing for refugees fleeing all manner of apocalypses. He was trained to transcend the everyday practices of government.”

Meanwhile, former FDA commissioner David Kessler, “a well-known operator” and “a renowned pugilist with a long list of enemies,” was hired to boost the supply of vaccines and, backed by the provisions of the Defense Production Act, all but threatened Moderna CEO Stephane Bancel to that end in a dramatically rendered Zoom meeting. “Kessler played the heavy,” Foer writes. “‘The president has said these doses will be available by the middle of May. They will be available by the middle of May.’” It worked, and “within months, the state, in whose capacities the public held so little trust, made it possible for any adult to walk into a pharmacy and obtain a lifesaving shot…. Technocracy—roundly maligned—had produced one of the best designed, most important government programs of all time.”

The presidency is never really about one man. Although Foer’s narrative is framed at the outset as a dive into Biden’s gifts and experiences as a leader—the “last politician”—the story he actually tells is of an expansive administrative state that has placed a substantial amount of power in the hands of officials—the Sullivans, the Klains, the Reeds—whom a president chooses to take on as staff. These advisers and technocrats are not elected or directly accountable to the public in any real way. Indeed, they’re often people that the average voter wouldn’t even recognize on TV. But for better or for worse, they’ve come to exert more and more influence on policy and our lives.

This fact can make ascribing true, independent, and direct agency to the person ostensibly in charge difficult. Yet, at times, Foer does so confidently nonetheless—even though his own account invites readers to ask how much of what’s already being called Biden’s “legacy,” in this book and elsewhere, can be credited to Biden personally. The decision to stay the course on withdrawal from Afghanistan was, of course, Biden’s; divining responsibility for how it was done is a more complicated matter.

That said, there are actions the administration has taken that clearly bear Biden’s fingerprints. The administration’s handling of Gaza, for instance, is in large part the product of Biden’s own stubbornness. Beyond his confidence in his ability to charm Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu into submission, Foer also reminds us—in passages that read even more gravely now than they did when the book was published last September—that the defense of Israeli policy, whether in the United States’ interests or not, has been one of Biden’s longest-standing commitments. “Biden,” Foer notes, “was old enough to have met with Golda Meir on the eve of the Yom Kippur War in 1973. He grew up in a world where most Americans, especially liberals, regarded Israel as a historical miracle and a sympathetic underdog.” Biden first met future House speaker Nancy Pelosi while she was organizing a fundraiser for Israel in the 1970s, Foer continues: “Biden was the keynote speaker. Pelosi loaned her Jeep, for the sake of squiring Biden around town so that he could extol the case for Zionism.”

While the American public is still largely supportive of Israel, the case for Zionism has taken a substantial hit in the aftermath of the Israeli response to Hamas’s October attack, particularly among Democrats.

Biden’s presidency has not been what most progressives would have wanted, and there’s little reason to believe, given Biden’s own politics and the Democratic Party’s current ideological composition, that it ever could have been, even if the Democrats had secured larger majorities in Congress than they had in the first two years of Biden’s term. It is true, thanks largely to the policy professionals that Biden has surrounded himself with, that it also hasn’t been the presidency most progressives feared. But Biden’s now-dismal standing in the polls as the campaign year starts in earnest suggests that he’ll have to rally more than tepid, grudging support from the Democratic base—and gain the faith of many more voters in the general electorate—in order to defeat Trump in November.

For a book called The Last Politician, it is notable that Foer’s narrative contains remarkably few instances of Biden engaging in what most would consider politics. There are almost no interactions chronicled with people who might be considered ordinary voters, and no notable episodes in which Biden tries to sell his policy agenda to the broader public. That’s not really an oversight on Foer’s part. Obama and Trump were highly visible and well-nigh inescapable presidents. But Biden has chosen to make himself scarce, partly to disguise his age and partly to fulfill a campaign promise—that anxious voters bewildered by the Trump years would finally be able to tune out the goings-on in the White House and in Washington. And they have—developing, as they’ve turned their attention elsewhere, a sense that Biden hasn’t been active or effective in addressing their concerns.

The crisis in Gaza hasn’t helped matters—especially since the broader public, including the overwhelming majority of Democrats, backs a cease-fire and a negotiated end to the conflict. Continued bloodshed may only deepen perceptions of Biden’s ineffectuality. But even if not, his reelection will surely depend on convincing voters that he has the energy and the political capital for a robust second term, in which he would be more of a felt presence than in the first. Technocrats and expertise may have put Bidenomics into action and carried much of his domestic policy agenda forward. But they will not help him at the polls.

We cannot back down

We now confront a second Trump presidency.

There’s not a moment to lose. We must harness our fears, our grief, and yes, our anger, to resist the dangerous policies Donald Trump will unleash on our country. We rededicate ourselves to our role as journalists and writers of principle and conscience.

Today, we also steel ourselves for the fight ahead. It will demand a fearless spirit, an informed mind, wise analysis, and humane resistance. We face the enactment of Project 2025, a far-right supreme court, political authoritarianism, increasing inequality and record homelessness, a looming climate crisis, and conflicts abroad. The Nation will expose and propose, nurture investigative reporting, and stand together as a community to keep hope and possibility alive. The Nation’s work will continue—as it has in good and not-so-good times—to develop alternative ideas and visions, to deepen our mission of truth-telling and deep reporting, and to further solidarity in a nation divided.

Armed with a remarkable 160 years of bold, independent journalism, our mandate today remains the same as when abolitionists first founded The Nation—to uphold the principles of democracy and freedom, serve as a beacon through the darkest days of resistance, and to envision and struggle for a brighter future.

The day is dark, the forces arrayed are tenacious, but as the late Nation editorial board member Toni Morrison wrote “No! This is precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.”

I urge you to stand with The Nation and donate today.

Onwards,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

Why Americans Are Obsessed With Poor Posture Why Americans Are Obsessed With Poor Posture

A recent history of the 20th-century movement to fix slouching questions the moral and political dimensions of addressing bad backs over wider public health concerns.

Thomas Müntzer’s Misunderstood Revolution Thomas Müntzer’s Misunderstood Revolution

A recent biography of the German preacher and leader of the Peasants’s War examines what remains radical about the short-lived rebellion he led.

Is It Possible to Suspend Disbelief at Ayad Akhtar’s AI Play? Is It Possible to Suspend Disbelief at Ayad Akhtar’s AI Play?

The Robert Downey Jr.–starring McNeal, which was possibly cowritten with the help of AI, is a showcase for the new technology’s mediocrity.

Possibility, Force, and BDSM: A Conversation With Chris Kraus and Anna Poletti Possibility, Force, and BDSM: A Conversation With Chris Kraus and Anna Poletti

The two writers discuss the challenges of writing about sex, loneliness, and the new ways novels can tackle BDSM.

Lore Segal’s Stubborn Optimism Lore Segal’s Stubborn Optimism

In her life and work, she moved through the world with a disarming blend of youthful curiosity and daring intelligence.

The Sheer Gusto of Jane DeLynn The Sheer Gusto of Jane DeLynn

1982’s In Thrall was a magnificent piece of queer fiction, at once comic and courageous.