Social Media Companies Are Having a Bad Moment

What if it were the start of a movement?

It would require, at this point, an unprecedented display of rhetorical gymnastics—or perhaps the miracle unearthing of some consensus-reversing data—to argue with any coherence that social media has been good for the American psyche. You’re probably familiar with the most alarming statistics: Between 2010 and 2019, rates of depression and anxiety in the United States rose by more than 50 percent; the suicide rate for adolescents rose by 48 percent, and for girls ages 10 to 14 by 131 percent. There are countless disturbing trend lines, each with a strong link to social media usage. Maybe it was still possible, a few years ago, to reasonably claim that concern about the effects of a platform like Instagram was no different from the kind of hand-wringing that has accompanied every other technological advancement of which we are now appreciative. But with each passing day, you have to be more of a deluded “techno-optimist” windbag to believe that.

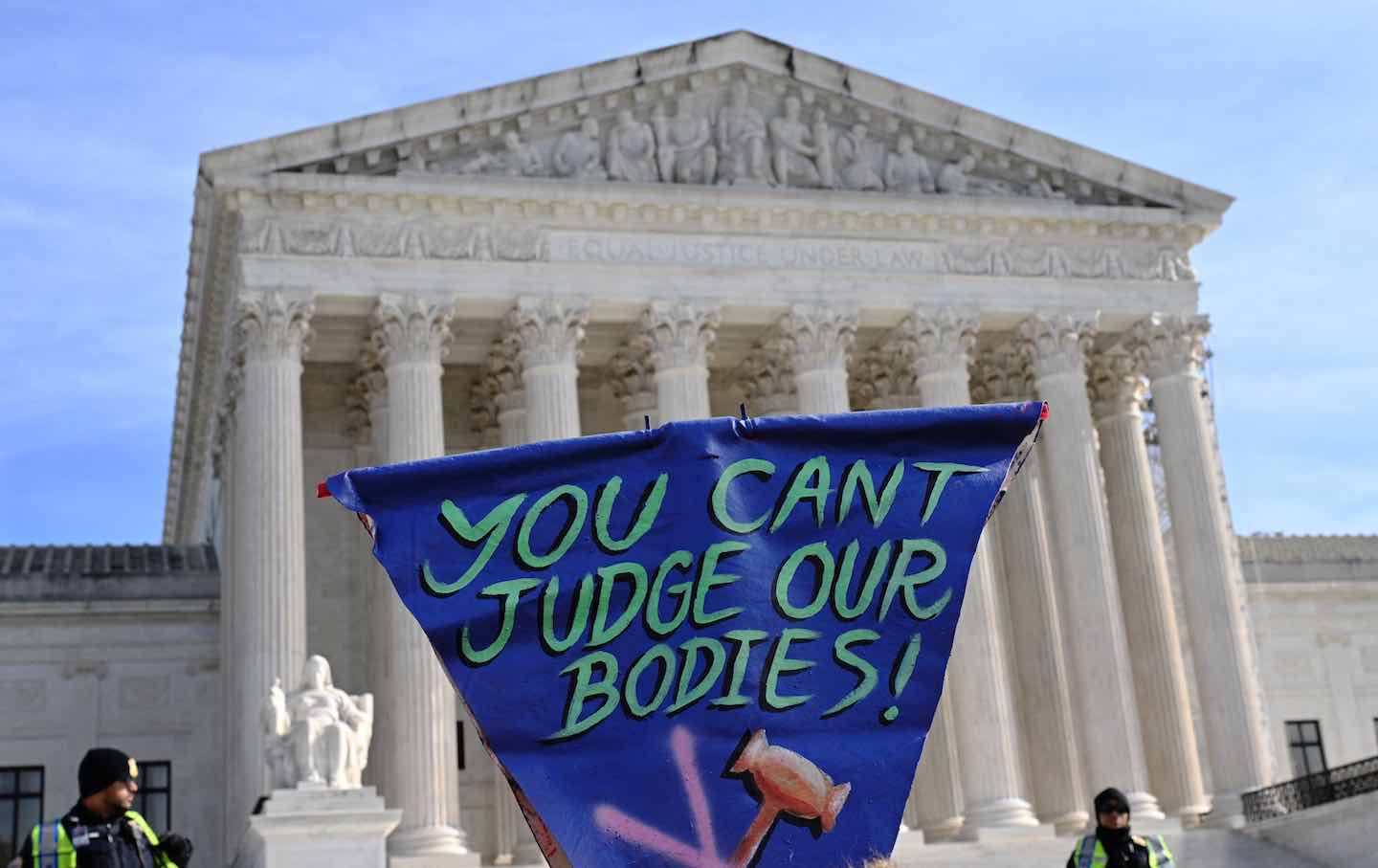

Social media companies and their apologists find themselves in an especially rough moment right now. Sociologist Jonathan Haidt has just released a new book, The Anxious Generation, which puts the severity of the screen-induced mental health crisis out of the question. The House just passed the TikTok ban, and bipartisan bills to regulate social media are moving forward in the Senate. State legislatures in Vermont, Minnesota and Maryland are contemplating bipartisan bills modeled to create greater online protections for kids. For a while, it was unclear whether any substantial anti–social media resistance would take shape. It’s happening now.

What’s strange about this moment, though—and what’s strange about the social media issue in general—is the general absence of a collective Gen Z voice in the discourse. We are the most affected, and yet we have little to say. Columnists, school principals, religious leaders, the surgeon general, Republican and Democratic lawmakers alike are all going after social media companies. But we—whom history will surely remember as a generation defined by phones—are comparatively quiet.

It’s not that we don’t understand the problem. We can see it on a political level (only in our Age of Phones could someone like Trump become president) and feel it on a personal one (the constant pull of cynicism, the retreat into solipsism, the general degradation of our ability to think and focus and inhabit meaningful states of mind). We know about the ways in which social media short-circuits or trivializes empathy, and thus hinders the democratic process. We are concerned by our collective addiction and conscious of it as such. We may find something patronizing in the tone of the “get off your phone” advocates—Haidt, to us, may sound a bit too much like a parent in alarmist mode—but, by and large, we don’t refute the diagnosis.

Ask the average 20-year-old what they think about social media and the answer will likely be negative. Last year, the University of Chicago published a working paper that found that 57 percent of college students who are active users of Instagram would “prefer to live in a world without the platform.” The experimenters asked the students how much they would have to be paid to get rid of their social media. Fifty dollars was the average answer. But “if most others” deactivated their social media, the average student would pay to have that happen. We’ve come to see the daily bombardment of electronically mediated stupidity as just another quality of life that must be weathered, depressing but immutable, like some constant rain.

It is difficult for young people to refuse social media for a number of reasons that aren’t our fault—the apps are engineered to be addictive and are often offered to us at a young age. (The cigarette comparison is fitting, though you could persuasively argue that some social media executives have knowingly exploited young consumers to a far greater extent than the cigarette execs did.) An additional explanation for our inability to envision an anti–social media movement—akin to the social justice or gun control movements in which many of us participated—is this: We intuitively feel that we’re supposed to reject our elders’ attempts to control our behavior and thought. But when it comes to the phone issue, it’s the social media executives who are controlling our behavior and thought, and it’s the fretful elders who are right about that. Weirdly, then, our rebellion will have to be with the finger-wagging Gen Xers, to some extent, and not against them. It’s a psychological adjustment as counterintuitive for us as it is necessary. After all, such an intergenerational alliance might be the only force powerful enough to break the tech lobby’s grip on Capitol Hill.

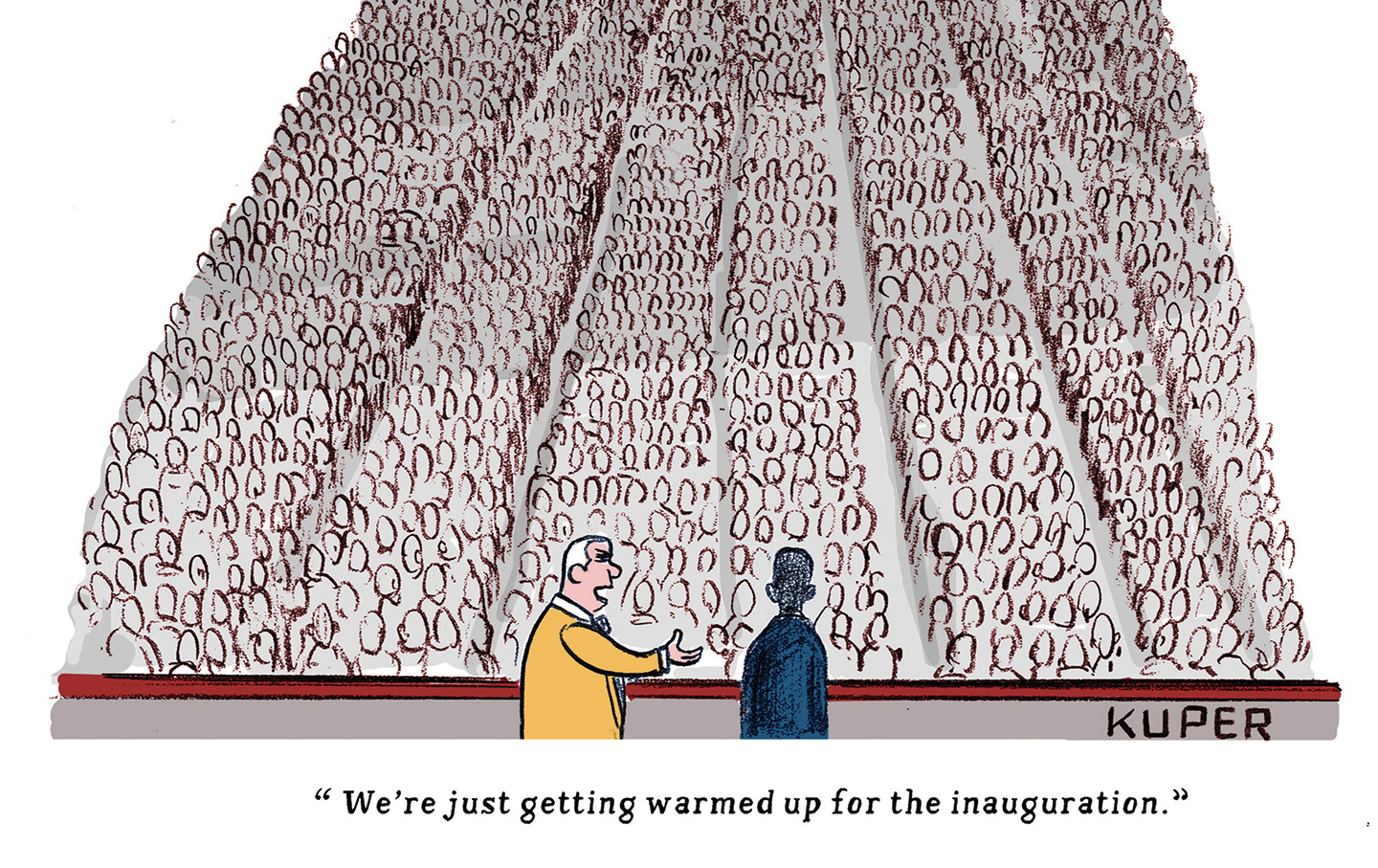

When we think today about great American social movements, we turn most often to the 1960s: the civil rights and anti-war movements (which were often characterized by young people rejecting the prevailing ethical concerns of their parents). But perhaps it’s more useful to draw from a different social crusade. In How to Do Nothing, Jenny Odell cites the 1934 West Coast Waterfront Strike as an apt model for social media resistance. The strike, which spanned nearly 2,000 miles, affected all of San Francisco. After police killed two employers who broke the picket line, 100,000 people across the city joined the strike. What we need now, Odell writes, is a similar project of “refusal, boycott, and sabotage”—a “spectacle of noncompliance that registers on the larger scale of the public.”

Strikes, of course, don’t end workers’ relationships with their employers; they restructure them. A total renunciation of the online world is neither pragmatic nor necessary. But an assertion of collective power is. There are members of our generation who have taken it upon themselves to forge one. Emma Lembke founded Log Off a few years ago, when she was a senior in high school. Her organization is committed to helping young people develop healthier relationships with social media, including spending much less time on the apps. Recent college graduate Trisha Prabhu, through an effort she created called ReThink, is creating technology to counter online hate and make social media more humane.

These activists impel us not to submit to the algorithms. They remind us of what Zadie Smith wrote about millennials and Facebook 14 years ago, in a key formulation of phrase equally applicable to Gen Z now: “The software currently shaping their generation is unworthy of them. They are more interesting than it is. They deserve better.” For over a decade, we’ve been trapped in an online infrastructure designed by people who have little interest in the common good. The entire ethos of social media can be located in a single sentence—penned with exceptional, unblinking amorality by aspiring-MMA fighter Mark Zuckerberg—from an early internal Facebook memo: “A squirrel dying in front of your house may be more relevant to your interests right now than people dying in Africa.” That’s the kind of thinking—inane, corporate, and so maddeningly small—that birthed the social media revolution. It will continue to shape us so long as we fail to see these platforms, and the people behind them, as the affronts that they are.

If there was ever a time to refuse social media as we know it, it’s upon us. We’ve arrived at a moment of reckoning. Will we turn the moment into a movement?