When We Occupied Columbia in 1978, the University Didn’t Call the NYPD

Campus administrators met student demands to divest from apartheid-era South Africa. What’s changed?

In May of our senior year, my friends and I—along with some 300 others—occupied the lobby of Uris Hall, directly across from a trustees’ meeting in Low Library, Columbia’s administration building, to demand that the university divest from companies with ties to South Africa. This was 1978: Jimmy Carter was in the White House, the liberation (as we would have put it) of Saigon had occurred just three years earlier, and with the United States not at war (at least overtly) anywhere in the world, we turned our attention abroad, to the apartheid regime of South Africa—a regime opposed by Carter but sustained by Wall Street. For those of us who came to Morningside Heights with the protests of 1968 very much on our minds, our chance to answer the call of history arrived just in time.

Although I can still recall the wild energy of that occupation—my first real experience of the power of solidarity—I had forgotten why and under what circumstances it ended. Final exams? Graduation? It turns out that we ended it because we had won: The university senate voted to sell the school’s holdings in any company that displayed “indifference” to the apartheid regime, as well as pull its money from the banks doing business there. Though less than the complete divestiture that we’d demanded—and achieved, a few years and several demonstrations later—it seemed like enough of a victory to allow for a withdrawal (though many of us wore white armbands in protest at graduation a few days later). We most certainly did not see our peaceful (if rowdy) demonstrations forcibly broken up by the New York Police Department in full riot gear. The trauma of police violence on campus from 10 years before was still too raw for any university administrator to risk reopening those wounds. In 1978, professor Edward Said—who would become the most prominent spokesman for the Palestinian cause (as well as music critic for The Nation)—was known on campus mainly as a Conrad scholar with a sideline in literary theory.

Unlike her colleagues at Harvard and the University of Pennsylvania, Columbia’s current president, Minouche Shafik, did not fall into the traps laid by her congressional inquisitors; her robust denunciation of antisemitism was doubtless gratifying to (some) major donors and local politicians. But on the heels of her craven willingness to throw pro-Palestinian faculty (including frequent Nation contributor Katherine Franke) under the bus, and her blatant disregard for academic freedom, Shafik’s decision to bring in the NYPD was a catastrophic failure of judgment that renders her unfit to remain in office.

Writing this as I am during Passover—when Jews are commanded not only to celebrate our liberation from bondage but to retell the story as if we had been enslaved by Pharoah ourselves—I’m more aware than usual of the ironies of history, and of the enduring bitterness when one nation’s freedom comes at the expense of another’s. And of the price in blood (see Jack Mirkinson), and conscience, when victims become persecutors—with or without divine intervention.

So it is a great pleasure to draw your attention to the seasonal abundance of our Spring Books issue—where generational politics will also figure in Tope Folarin’s review of Vinson Cunningham’s Obama administration novel, Sam Adler-Bell’s essay on burnout and the Bernie generation, Edna Bonhomme’s consideration of the travails of millennial divorce, and Sarah Schulman’s reflections on Keith Haring.

And to offer a different kind of liberation narrative: Amy Littlefield’s cover story on the abortion pill underground that has sprung up in response to the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision. (And for another ’60s vibe with a long tail, see Alissa Quart’s account of psychedelic inequality.)

Not to mention a suite of dispatches—Wen Stephenson’s from Nepal, Lydia Kiesling’s from Portland, Oregon, and Kim Kelly’s from WrestleMania XL—as well as Stephanie Burt on Joanna Russ, Nicolás Medina Mora on Gabriel García Márquez, and Elias Rodriques on Nell Irvin Painter. Plus provocative columnists, sagacious editorials, and gorgeous art and illustrations. A feast for the eyes and the mind!

D.D. Guttenplan

Editor

We cannot back down

We now confront a second Trump presidency.

There’s not a moment to lose. We must harness our fears, our grief, and yes, our anger, to resist the dangerous policies Donald Trump will unleash on our country. We rededicate ourselves to our role as journalists and writers of principle and conscience.

Today, we also steel ourselves for the fight ahead. It will demand a fearless spirit, an informed mind, wise analysis, and humane resistance. We face the enactment of Project 2025, a far-right supreme court, political authoritarianism, increasing inequality and record homelessness, a looming climate crisis, and conflicts abroad. The Nation will expose and propose, nurture investigative reporting, and stand together as a community to keep hope and possibility alive. The Nation’s work will continue—as it has in good and not-so-good times—to develop alternative ideas and visions, to deepen our mission of truth-telling and deep reporting, and to further solidarity in a nation divided.

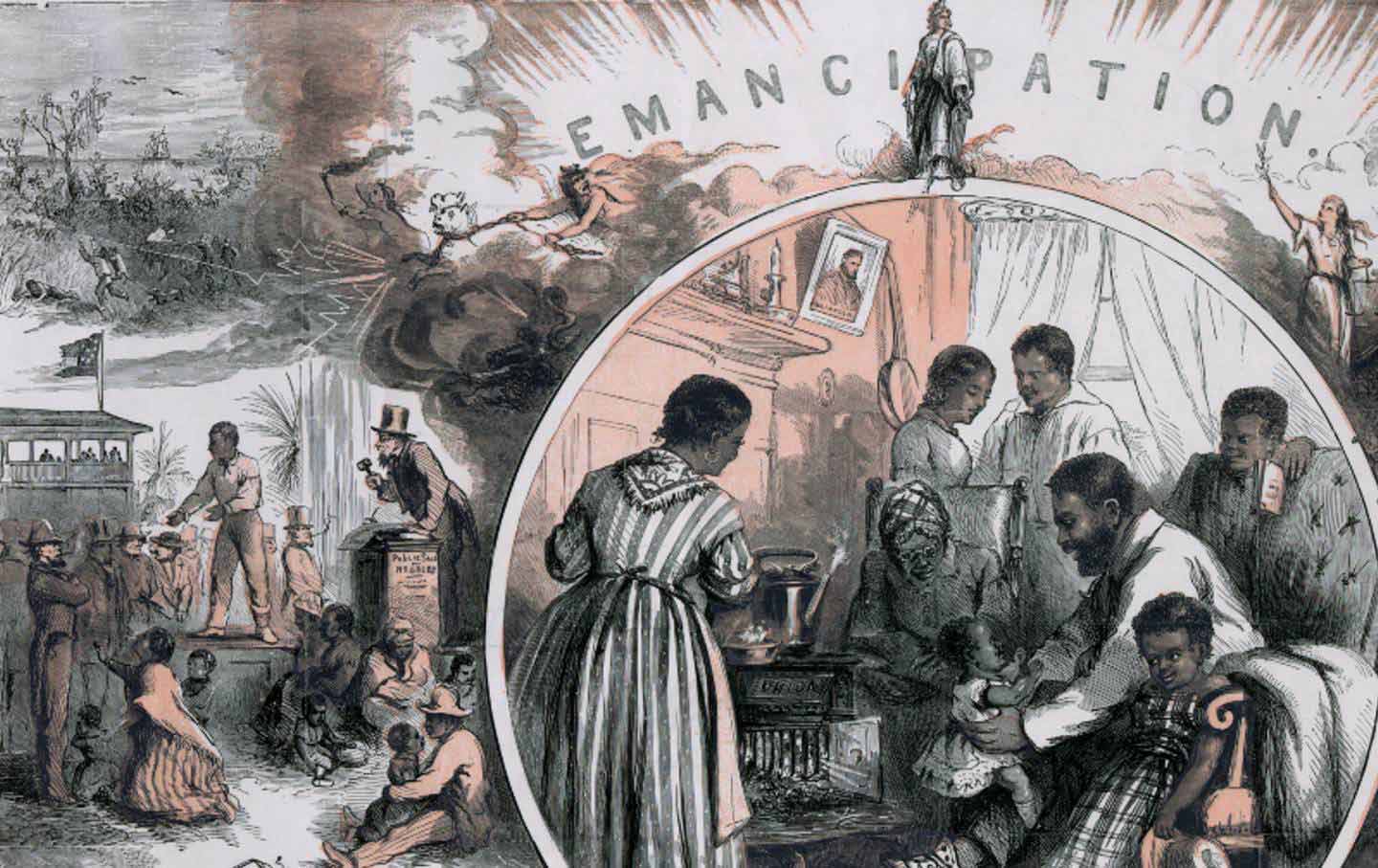

Armed with a remarkable 160 years of bold, independent journalism, our mandate today remains the same as when abolitionists first founded The Nation—to uphold the principles of democracy and freedom, serve as a beacon through the darkest days of resistance, and to envision and struggle for a brighter future.

The day is dark, the forces arrayed are tenacious, but as the late Nation editorial board member Toni Morrison wrote “No! This is precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.”

I urge you to stand with The Nation and donate today.

Onwards,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation