What Is Policing For?

Sociologist Michael Sierra-Arévalo’s recent book explains how an obsession with violence has defined the police’s purpose and worldview.

Police in Baltimore, Maryland, 2015.

(Photo by Andrew Burton / Getty Images)

In a working-class neighborhood in a midsize Northeastern town, a police officer is driving his cruiser down a darkened street when he passes a group of six Latino teenagers walking and talking together. “Look at these little shitheads,” he mutters. He stops his car, throws it in reverse, and backs down the one-way street, unholstering his pistol and laying it in his lap. When he reaches the group, all of whom are boys, he rolls down his window and, keeping the pistol in his lap, just out of sight, points it at them through the panel of the cruiser door. “What’s up, guys?” the officer says. “What’s up?” they reply. He questions them about how they’re doing in school; they joke nervously about their grades. Eventually, without acknowledging their jokes, the officer ends the encounter. “All right, you guys stay out of trouble,” he says and then drives away, slowly reholstering his pistol.

Books in review

The Danger Imperative: Violence, Death, and the Soul of Policing

Buy this bookIn the passenger seat, Michael Sierra-Arévalo, a sociologist at the University of Texas at Austin, silently observes the interaction. Soon enough, the officer explains the unholstered gun: “They would have been able to shoot at us in a split second if they wanted,” he says. “You have to be ready for that. Always have a plan of attack.”

This short but haunting exchange illustrates a central ethos of American law enforcement, as Sierra-Arévalo argues in a new book, The Danger Imperative: Violence, Death, and the Soul of Policing. In quietly reaching for his firearm, the officer was indulging a now-routine impulse. It may be irrational, given how rarely police are attacked. But policing, as a profession, is obsessed with violence and officer safety, a worldview that Sierra-Arévalo calls “the danger imperative.” Within its ambit, the officer’s actions make perfect sense.

A focus on danger pervades police culture, from drills in the academy to self-defense tactics on the street. Officers are taught from the start that the very people they are sworn to serve might harm them at any moment: Even if department policy states that they are never to draw a weapon unless an emergency arises, the philosophy of policing in America is to treat every interaction as a potential crisis. And despite the modern color-blind logic of the profession, police disproportionately use these tactics in poor communities of color, often causing harm.

“The danger imperative is policing’s governing institutional frame,” Sierra-Arévalo writes. More simply, it is “the ‘soul’ of policing.” The Danger Imperative studies several police departments around the country to catalog the often hidden mechanisms that animate police violence. Beyond that, Sierra-Arévalo reveals how danger has become a useful focus for a reactionary social project: A vigilant police force is a necessary ingredient in protecting the interests of both capital and the state. In an era when demands for racial and economic justice have reached a fever pitch, the book explains how a preoccupation with violence helps perpetuate a system of inequality.

It was Michael Brown’s death in Ferguson, Missouri, and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement that convinced Sierra-Arévalo that he should study cops. People filled the streets, decrying long-standing patterns of police brutality; the police responded with tear gas, nightsticks, and arrests. To some pundits, policymakers, and police representatives, these confrontations amounted to a “war on cops,” the latest rhetorical front in a counterrevolutionary battle, growing since the 1960s, that targeted protesters as criminal enemies. When disturbed citizens ambushed and killed police officers in New York City and Dallas, it only served as further proof that the thin blue line between chaos and order was under attack. Never acknowledged by this same commentariat is that policing today is safer than ever. It’s not danger-free, of course: Officers suffer a violent injury rate more than 16 times the national average for all jobs. But deaths in the line of duty have dropped by 75 percent in the last 50 years, and violence against police has not spiked since 2014.

Why, then, do police see threats all around them? To understand this phenomenon, Sierra-Arévalo spent four years, from 2014 to 2018, observing three police departments in the Northeast, the Southwest, and the West, pseudonymized as Elmont, Sunshine, and West River. From the moment that officers join the force, he found, they are bombarded with the message that the public is out to get them. In academy rooms bedecked with military imagery, instructors screen grisly videos of officers murdered on the job. “Reality-based” scenarios suggest, falsely, that hidden guns are common during traffic stops. A PRISim simulation video in Sunshine teaches recruits when to “neutralize” an armed suspect—and how to justify it despite the department’s stated policies. This tough-sounding “tactical” stuff far outweighs the instruction on defusing potentially violent situations. Elmont, for example, devotes 170 hours to weapons training and just 10 to de-escalation techniques. The ruling message of police education, Sierra-Arévalo writes, is that their work is defined by “a constant fight for survival that must be won at all costs.”

On the job, a barrage of information reiterates the lethal dangers of policing. Public memorials to fallen officers are ubiquitous. Elmont’s headquarters displays plaques for each officer killed on duty going back to the 19th century. Privately, officers possess a “hidden world of cultural artifacts” to commemorate the dead: bracelets, tattoos, and personal shrines. Meanwhile, the daily functions of the department reinforce the sense of threat. Sierra-Arévalo takes us into the “lineup” room where officers start their shift; there the walls are plastered with warnings about volatile gang members and exotic weapons. Supervisors distribute “hot sheets” with information about violent crimes around the region. Never mind that these offenses represent a tiny fraction of any agency’s thousands of routine calls for service; they take center stage in the police imagination. Occasionally, actual violence strikes. When an unruly crowd in West River injures an officer during an illegal street race, her colleagues understand the incident as confirmation of the widespread danger to police across the country in the wake of BLM. “This just goes to show how the climate is right now,” one tells Sierra-Arévalo. “It’s disturbing how violent and aggressive people are with officers.”

The perception of the public as dangerous and unruly is not limited, of course, to police. It reaches the highest levels of the state, transcending the partisan divide of mainstream politics. Thus every modern political elite, whatever their high-flown incantations in favor of “police reform” or “law and order,” must pay rhetorical tribute to the brave law-enforcement officers who put their lives in harm’s way so that the rest of us can stay safe. The ruling class has always been incentivized to breed a fear of the other among police: It serves to protect their interests. Our political economy creates an underclass, and that underclass must be managed. A certain measure of indoctrination, it seems, is necessary to convince agents of the state, transformed from ordinary citizens, that they are righteous in repressing the least powerful among us, and in doubling down when those disempowered take to the streets.

For police, the danger imperative is more than mere rhetoric. They are true believers, and it’s stunning to see how their fear materializes in real-world behavior, particularly toward the urban poor. It’s not that officers discuss these perceived threats in explicitly racial terms, Sierra-Arévalo writes. No longer do Black and Latino “superpredators” prowl our streets. Instead, police today justify violence in the race-neutral language of “tactics” and “officer safety.” But the fact remains that the police are disproportionately sent into communities of color. Because of historic racism, disinvestment, and abuse, these neighborhoods suffer the bulk of violent crime and therefore the brunt of police stops, arrests, and violence. In a wretched and unending cycle, police target a population that the state has largely abandoned.

Thus it is no wonder that police feel unsafe in the neighborhoods they patrol. The Danger Imperative documents the “safety-enhancing” tactics that officers routinely use—and how they go maddeningly wrong. Particularly eye-popping is the concept of “command presence,” a demeanor and appearance taught in the academy that “exudes authority” and is meant to maintain control over a volatile public. In practice, this often looks like plain old disrespect. One Elmont officer regularly shouts at people who question him. At one point, he barges into a woman’s apartment building when she asks whether he has a warrant, rather than simply explain that he’s trying to return her neighbor’s lost wallet. Ironically, in behaving so rudely, officers lethally “neutralize” whatever shreds of public trust they might otherwise enjoy, leading to more resentment and generating more danger.

In other scenarios, officers are simply not equipped to help, and the danger imperative causes them to perceive threats where none exist. When two Elmont officers respond to a family’s call to assist with their son’s mental health crisis, Sierra-Arévalo observes a harrowing situation. After the man behaves erratically and tries to leave the room, officers fear that he could be retrieving a weapon, so they instantly go “hands on,” wrestling him to the ground, pepper-spraying him in the face, and handcuffing him before an ambulance arrives to take him away. His family is furious. “Fucking pigs!” his sister yells. The man, who ends up being transported to the hospital for observation, was in acute mental distress and did little wrong aside from putting up a futile resistance to the officers’ rough treatment. These aggressive tactics are fairly commonplace—much more so than high-profile police killings. In 2018, officers pushed, grabbed, or struck 430,000 people nationwide; by comparison, they fatally shot 990. “Most police violence,” Sierra-Arévalo writes, “is used to preemptively assert control over interactions or in response to passive, nonviolent resistance.”

What is policing for? Far from creating safety, in America the profession has always been a means of asserting control. In its origins, policing as we know it today was created to put down slave revolts. During the civil rights era, police brutally suppressed peaceful marchers. Today, police remain the frontline force cracking down on demonstrations for racial and economic justice, and the danger imperative remains a powerful tool in explaining away their actions. Just last year, when police shot and killed an unarmed activist opposing Atlanta’s proposed Cop City training facility, they claimed self-defense and escaped repercussions. But these continued confrontations announce a new and durable public refusal to accept the violence that police mete out. “Something has changed in America,” Tobi Haslett wrote in n+1 in 2021, reflecting on the historic uprisings over the police murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis. “The rebellion didn’t just release a jet of fury but lodged the riot, without apology, in the very rhythm of political life.”

Sierra-Arévalo’s conclusions are, in part, a product of that change. Having spent more than 1,000 hours watching officers invent threats where there were none (be it a homeless person in the park or a crowd of political protesters) and abuse their power (whether by handcuffing innocent motorists or tackling mentally ill patients), he recognizes the cultural and institutional limits of reform. The book largely arrives at non-reformist solutions, ones that don’t rely on the police to solve society’s ills. Adding community-strengthening nonprofits can reduce murder and overall crime: They bolster people’s ability to set expectations for neighborhood safety. Environmental fixes like greening vacant lots can also cut violence: They remove signs of blight and physical opportunities to do harm. Expanded budgets for violence interrupters, mental health practitioners, and restorative justice programs can provide for community needs—all without resorting to the punitive policies that have filled America’s prisons.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →“Just as reformers have been afforded decades and billions of dollars to realize halting change in police culture and operations,” Sierra-Arévalo writes, “the same allowance should be given to those invested in providing for public wellbeing without policing and its attendant harms.” Above all, this is what the public has been demanding: time and resources to create community safety on their own terms. Change can feel impossible, but the most dangerous thing we could do is to continue accepting policing as usual.

More from The Nation

The Agony of Aaron Rodgers The Agony of Aaron Rodgers

Is he the world’s most interesting athlete or is he just a washed-up crackpot?

Can You Understand Ireland Through One Family’s Terrible Secret? Can You Understand Ireland Through One Family’s Terrible Secret?

In Missing Persons, Clair Wills's intimate story of institutionalized Irish women and children, shows how a family's history and a nation’s history run in parallel.

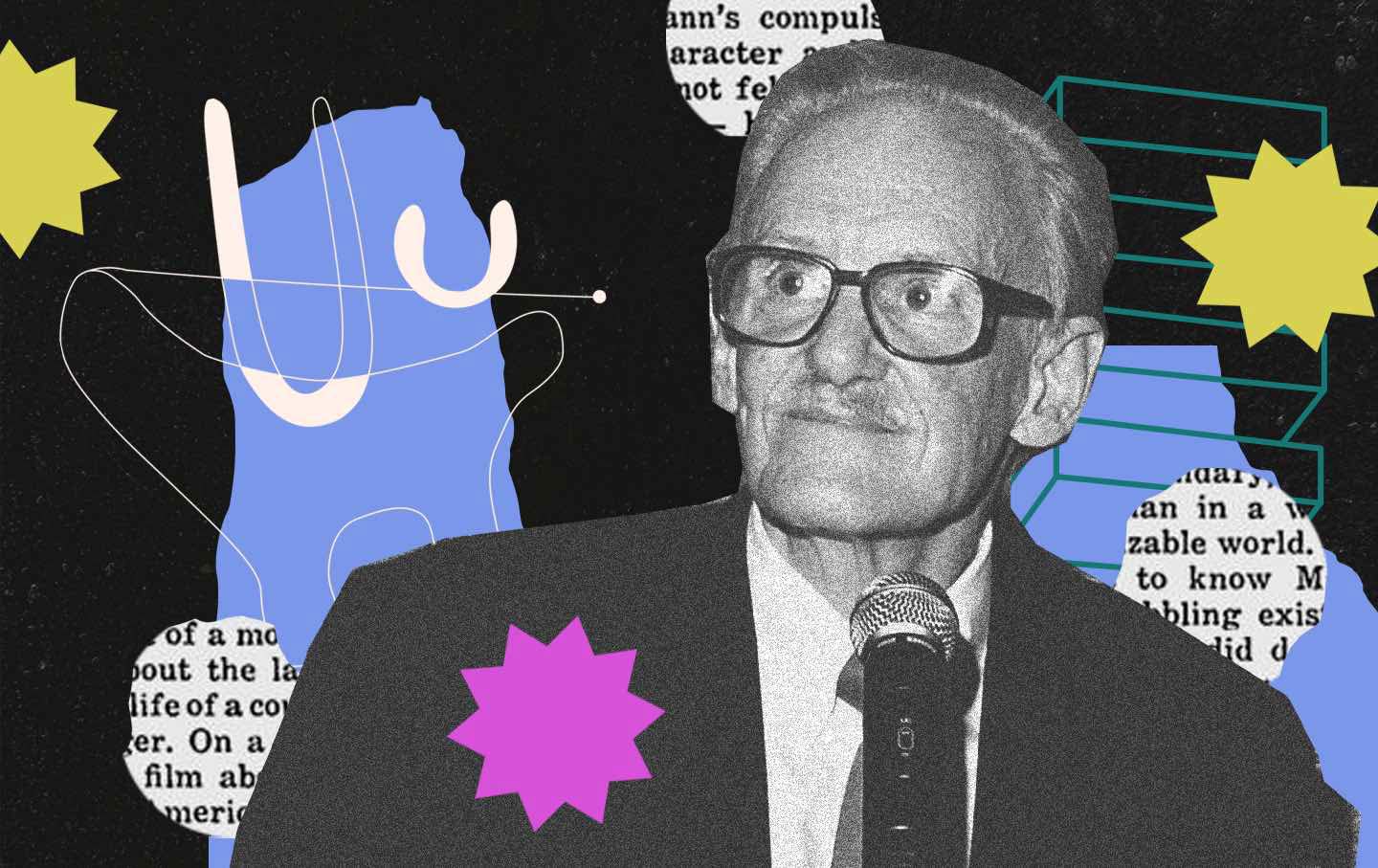

Peter Schjeldahl’s Pleasure Principle Peter Schjeldahl’s Pleasure Principle

His art criticism fixated on the narcissism of the entire enterprise. But over six decades, his work proved that a critic could be an artist too.

How the Western Literary Canon Made the World Worse How the Western Literary Canon Made the World Worse

A talk with Dionne Brand about her recent book, Salvage, which looks at how the classic texts of Anglo-American fiction helped abet the crimes of capitalism, colonialism, and more...

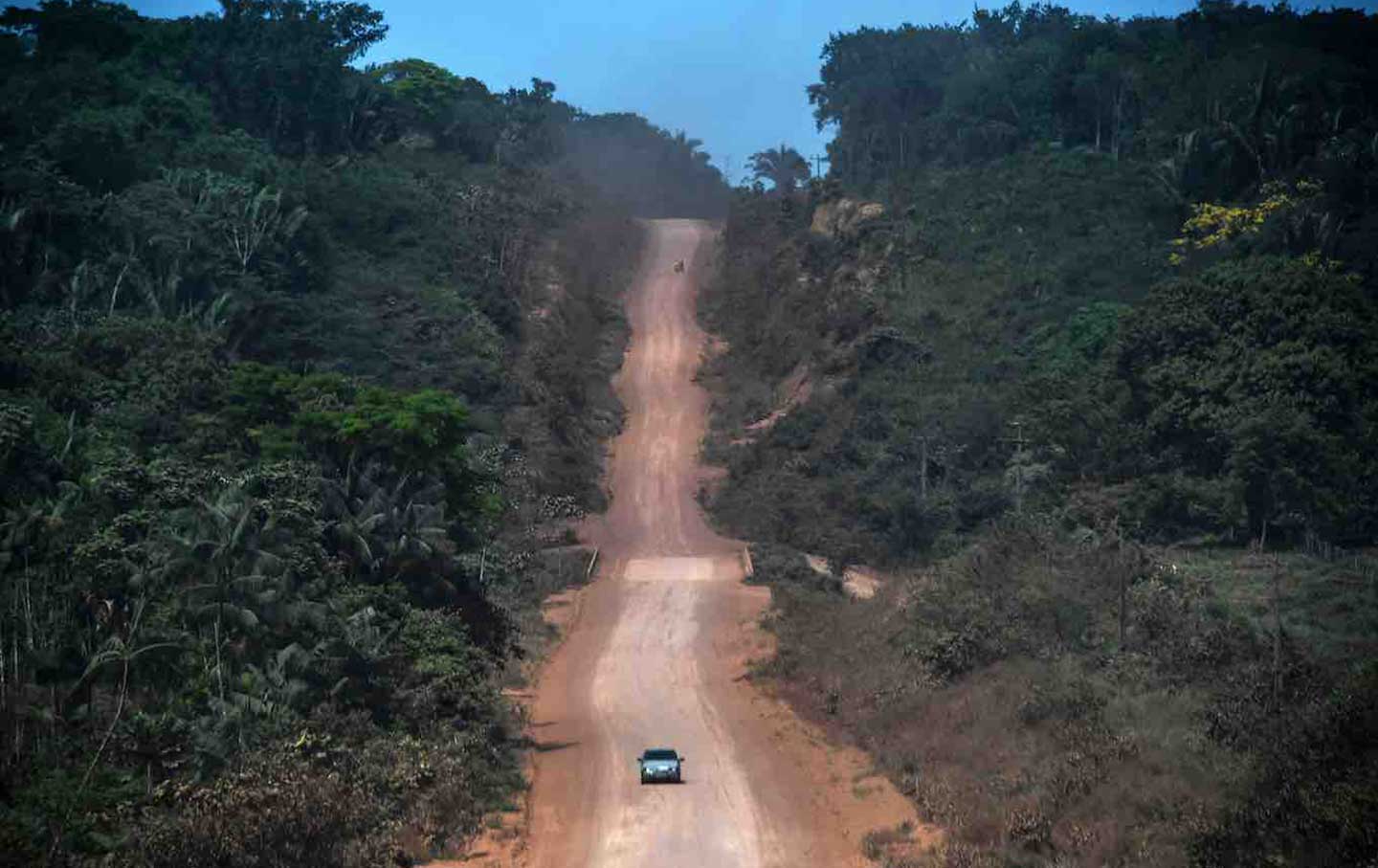

Along the Roads That Built Modern Brazil Along the Roads That Built Modern Brazil

José Henrique Bortoluci's What Is Mine tells the story of his country’s laborers, like his father, who built its infrastructure, and in turn its fractious politics.

The Long History of the "Elsewhere Museum" The Long History of the "Elsewhere Museum"

Can the ethnographic museum be reinvented?