Is Sports Gambling a Public Health Crisis?

Why a progressive approach might be a national intervention.

“An illness, progressive in its nature, which can never be cured, but can be arrested.” Those words may sound like they describe some neurodegenerative disorder—but in fact, they’re how Gamblers Anonymous defines compulsive gambling. GA hosts more than 1,200 weekly meetings for the estimated 10 million Americans with gambling problems.

If you’re familiar with how other public health crises have been handled in America, you might expect this problem to be ignored by lawmakers. But the truth is, they’re making it worse. In recent years, legislatures across the country have broadly legalized one of the most habit-forming types of gambling: sports betting. Thirty-eight states and the District of Columbia now authorize the practice.

That means it’s currently easier to wager a month’s salary on the NBA Finals than it is to get an abortion.

This wave of legalization has ripped through the country with minimal murmuring from progressives—perhaps a reflection of a broader laissez-faire approach to matters of the personal life on the left. After all, it’s ordinarily a compassionate instinct to let people do what they want with their time and money. And yet a categorical gulf exists between, say, the right to marriage and the freedom to entangle yourself in an inherently exploitative scheme. That’s why the truly progressive approach to sports betting might be a national intervention.

As with more than a few of our current systemic woes, the sports betting craze originates from a Supreme Court decision aimed at safeguarding states’ rights. In 2018, Elena Kagan joined the court’s five conservative justices to overturn a federal sports betting ban. The suit was brought by Democratic New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy over gambling legalization passed by his predecessor, Chris Christie. It took an inspiring bipartisan effort to kick-start this spiral.

The six years since that ruling have seen Americans lose at least $245 billion on sports wagers. And given that rates of gambling addiction are highest among the unemployed, the elderly, and the poor, these losses have been disproportionately borne by those who could least afford them.

Figures like these upend the classic pro-gambling argument that its legalization benefits society by raising revenue for services like public education. According to research on gambling’s economic impact in New Jersey, online casinos have indeed generated hundreds of millions of dollars in taxes. But that influx is canceled out by hundreds of millions of dollars in gambling-related costs, like welfare and homelessness. In reality, vulnerable people are losing more than they’re gaining.

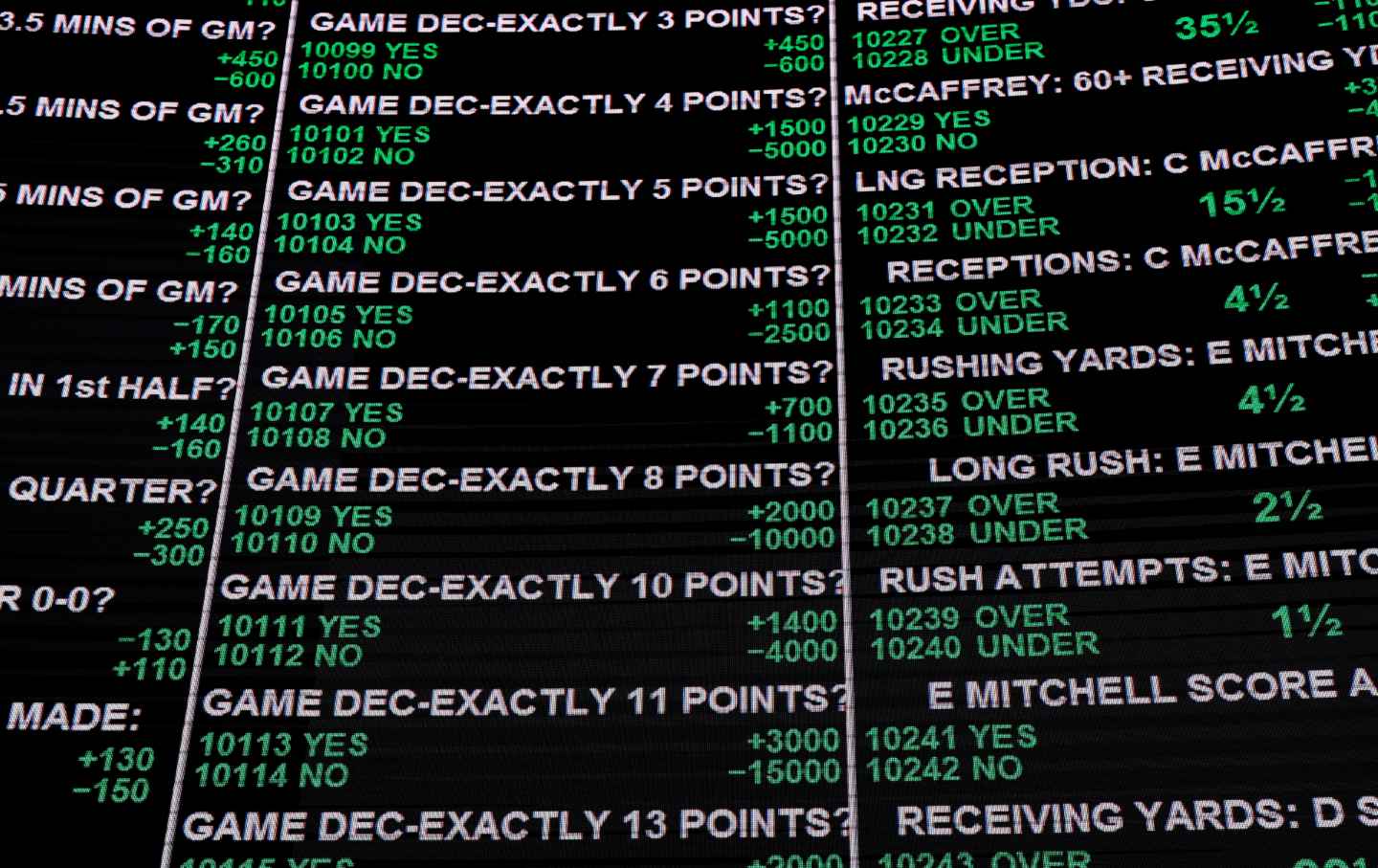

This is by design. And entire industries have conspired to exacerbate the crisis. Tune in to any game today, and you’ll find yourself watching not just the points on the board but also the point spread that broadcasters like ESPN continuously update. Betting magnates have bought up teams: The Adelson family, which operates the multibillion-dollar Sands casino corporation (and bankrolls everyone’s favorite convicted felon president), now owns the Dallas Mavericks. Even the players—and their interpreters—can’t resist the allure of winning big off the field. Sports and sports betting are becoming one and the same.

Maybe most alarming is another convergence—sports betting with smartphones. Valiantly named apps like FanDuel and DraftKings have taken the algorithmic addictions of the perpetual scroll and combined them with the retro fixation of rolling the dice. Dr. Tim Fong, the director of UCLA’s Gambling Studies program, has described these apps as creating a “casino in our pockets.” And they haven’t even fully integrated AI yet.

By far, the most vulnerable are the most online. More and more young people are making wagers in their pajamas, in between classes, and, yes, in the shower. In targeting the youth, betting moguls have successfully future-proofed their industry, if you ignore the fact that their customers will endure an increased risk of suicide for the rest of their lives.

This is not to suggest that we need to take the Carry Nation approach and prohibit sports gambling altogether. But a little regulation could do a lot of good. In Congress, Paul Tonko (D-NY) has urged treating these developments as a public health crisis, the same way the federal government did with cigarettes. His “Betting on Our Future Act” would make glamorous sports betting ads go the way of the Marlboro Man. By banning commercials like the two star-studded spots from this year’s Super Bowl, seen by 123 million people, the bill would stymie the rapid romanticization of a business historically associated with broken kneecaps.

Perhaps predictably, Tonko’s legislation has gone nowhere. And a proposal cosponsored by Senator Richard Blumenthal to fund treatment for gambling addiction hasn’t gathered much momentum, either. Combine that with the Supreme Court’s demonstrated proclivity for blocking federal intervention on this issue, and it may be that, at least in the immediate term, this fight will have to play out in the states—which thus far have been the main drivers of sports betting legalization.

Thankfully, some state lawmakers are beginning to realize they may have gone too fast, too soon. Spikes in the number of young people calling gambling hotlines so concerned Wayne Fontana, a state senator in Pennsylvania, that he introduced a bill banning the use of credit cards for online betting. Local legislators across the country could follow Fontana’s lead. Otherwise, more people will find themselves descending more deeply into more unpayable debt, at a time when loan default rates are already hitting record highs. How many more wagers do we have before it all goes bust?

Support The Nation this Giving Tuesday

Today is #GivingTuesday, a global day of giving that typically kicks off the year-end fundraising season for organizations that depend on donor support to make ends meet and enable them to do their work—including The Nation.

To help us mobilize our community in this critical moment, an anonymous donor is matching every gift The Nation receives today, dollar-for-dollar, up to $25,000. That means that until midnight tonight, every gift will be doubled, and its impact will go twice as far.

Right now, the free press is facing an uphill battle like we’ve never faced before. The incoming administration considers independent journalists “enemies of the people.” Attacks on free speech and freedom of the press, legal and physical attacks on journalists, and the ever-increasing power and spread of misinformation campaigns all threaten not just our ability to do our work, but our readers’ ability to find news, reporting, and analysis they can trust.

If we hit our goal today, that’s $50,000 in total revenue to shore up our newsroom, power our investigative reporting and deep political analysis, and ensure that we’re ready to serve as a beacon of truth, civil resistance, and progressive power in the weeks and months to come.

From our abolitionist roots to our ongoing dedication to upholding the principles of democracy and freedom, The Nation has been speaking truth to power for 160 years. In the days ahead, our work will matter more than it ever has. To stand up against political authoritarianism, white supremacy, a court system overrun by far-right appointees, and the myriad other threats looming on the horizon, we’ll need communities that are informed, connected, fearless, and empowered with the truth.

This outcome in November is one none of us hoped to see. But for more than a century and a half, The Nation has been preparing to meet it. We’re ready for the fight ahead, and now, we need you to stand with us. Join us by making a donation to The Nation today, while every dollar goes twice as far.

Onward, in gratitude and solidarity,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

Stopping Trump From Using the LA Olympics to Burnish His Strongman Image Stopping Trump From Using the LA Olympics to Burnish His Strongman Image

Activists, community leaders, and organizers are already teaming up to prevent LA28 from becoming an echo of the 1936 Nazi Olympics.

The GOP Push to Deregulate Childcare, One State at a Time The GOP Push to Deregulate Childcare, One State at a Time

From Kansas to South Carolina, Republican have come up with a terrifying solution to the childcare crisis: remove some of the basic guardrails ensuring safe, quality care for youn...

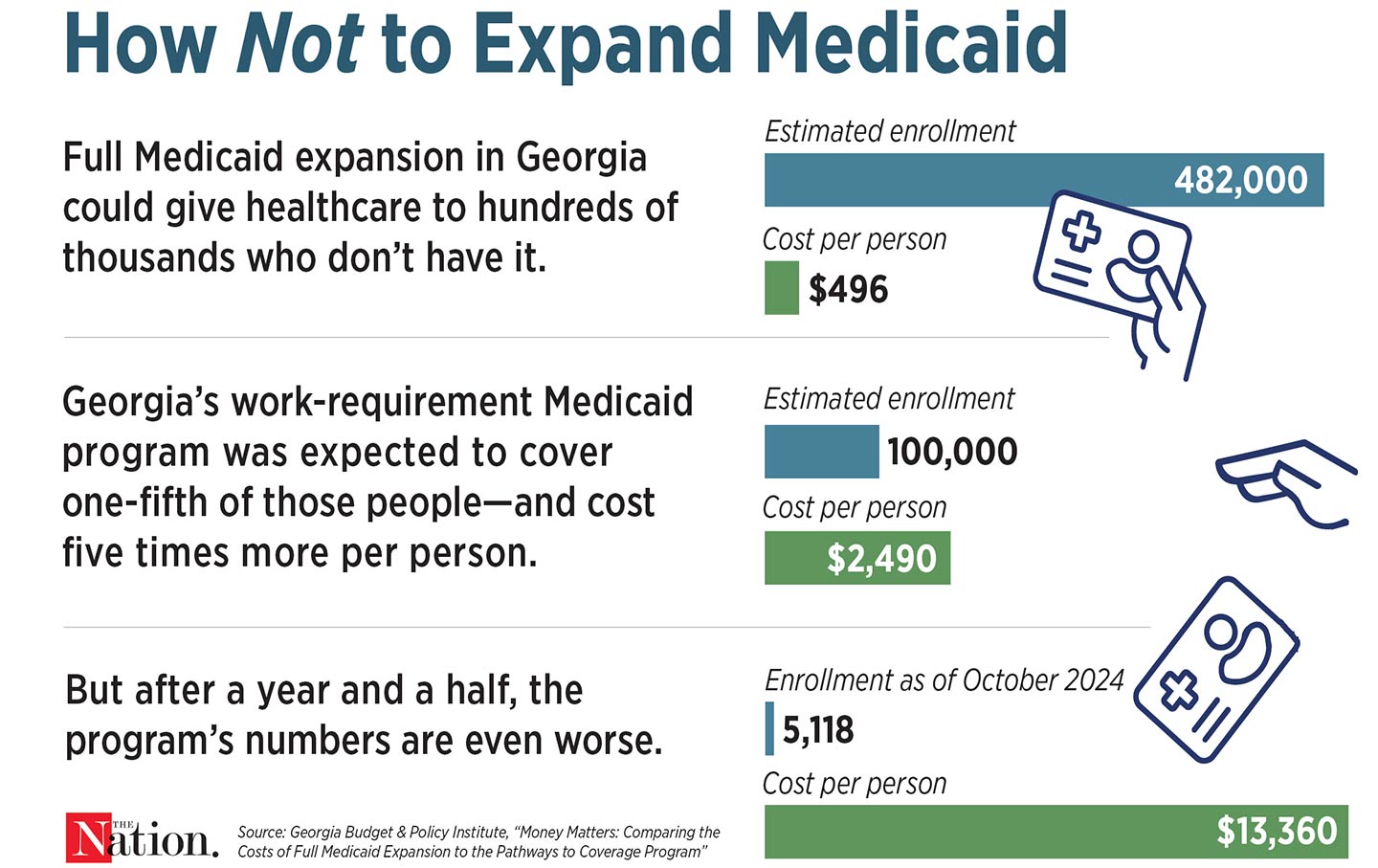

Georgia’s Disastrous Medicaid Work Requirements Georgia’s Disastrous Medicaid Work Requirements

Georgia’s Republican governor, Brian Kemp, said that 345,000 people would enroll in the state’s Medicaid program, which has strict work requirements—so far just 5,118 have.

Donald Trump’s Government of Gangsters Donald Trump’s Government of Gangsters

Who is being naïve now?

Illinois Has Put an End to the Injustice of Cash Bail Illinois Has Put an End to the Injustice of Cash Bail

Amid a national backlash against criminal justice reform, Illinois has achieved something extraordinary. It’s working better than anyone expected.

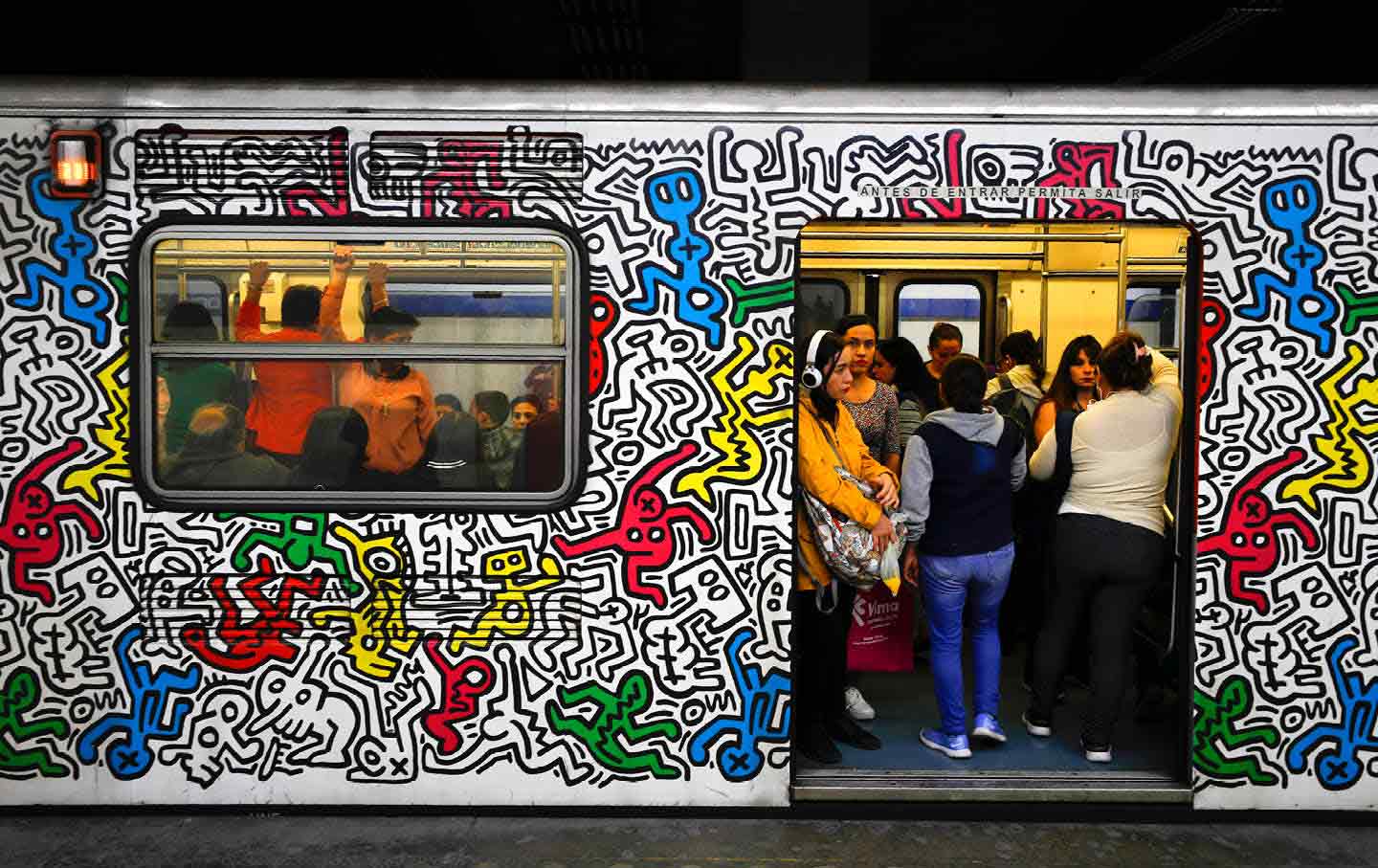

The Nonstop Gay Sex Party on the Mexico City Subway The Nonstop Gay Sex Party on the Mexico City Subway

The city’s metro hosts—and authorities unofficially sanction—a queer institution unlike any other.