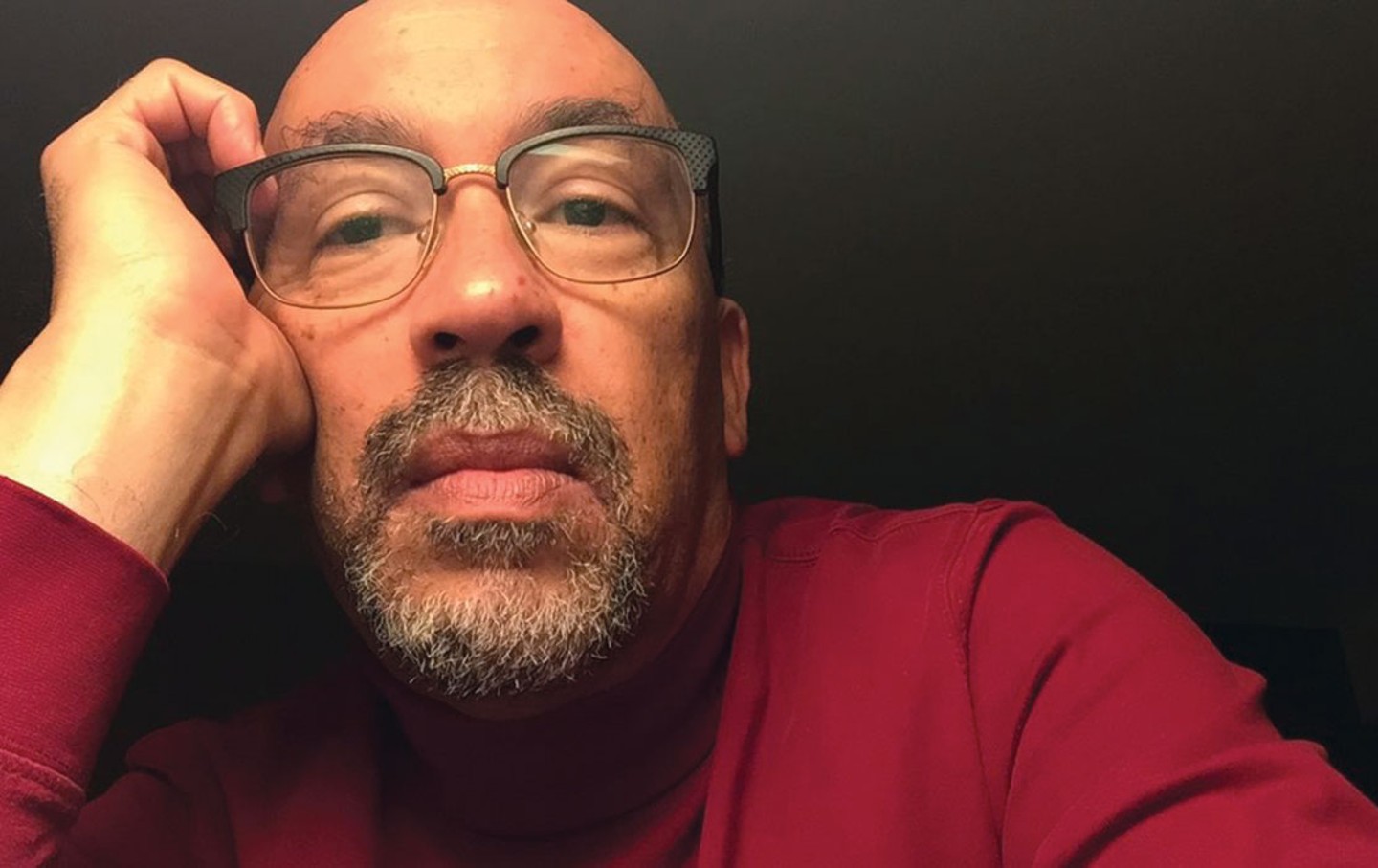

The Metamorphosis of Kyrie Irving

The Dallas Mavericks guard could’ve left the NBA a villain, but he’s now played long enough to become a hero.

The NBA Finals pit the Dallas Mavericks against the Boston Celtics, and during tonight’s game one, millions of eyes will be on former Celtic Kyrie Irving, who has been making magic throughout the Mavericks’ improbable run to the 2024 championship. When Irving joined Boston as a baby-faced 26-year-old, the fit was, to put it mildly, not ideal. After two disappointing years, he left town for the Brooklyn Nets. In Boston, he feuded with teammates and joined the long list of athletes who called out the city’s racism. When Irving returned to Boston, a fan threw a water bottle at him. Irving also gave the Celtic faithful the one-finger salute and stomped on the head of their leprechaun mascot painted at half-court.

This won him no friends in the press, who accused Irving of being what they call “a locker-room cancer.” Irving’s time in Brooklyn—alongside future Hall-of-Famers James Harden and Kevin Durant—only seemed to cement this reputation when a Nets club with championship-or-bust aspirations became the sports equivalent of box-office poison. There were injuries, chemistry problems, and a toxic atmosphere that made, for all the talent and expense, an unwatchable result. (Call them Kevin’s Gate.)

During the pandemic, Irving earned broad disapproval—and the love of Ted Cruz—for refusing to take the vaccine. This also disrupted the franchise, as state law prevented him from playing games in New York City.

Today, Irving is 32, and is, in his own words, a different human being. It’s a sentiment seemingly universally agreed upon across the media landscape. The press accepts that Irving has changed for the better not because of his conversion to Islam or new family life but because the Mavericks are winning, and in this moral ecosystem, the proof of not just greatness but goodness is found only in wins and losses.

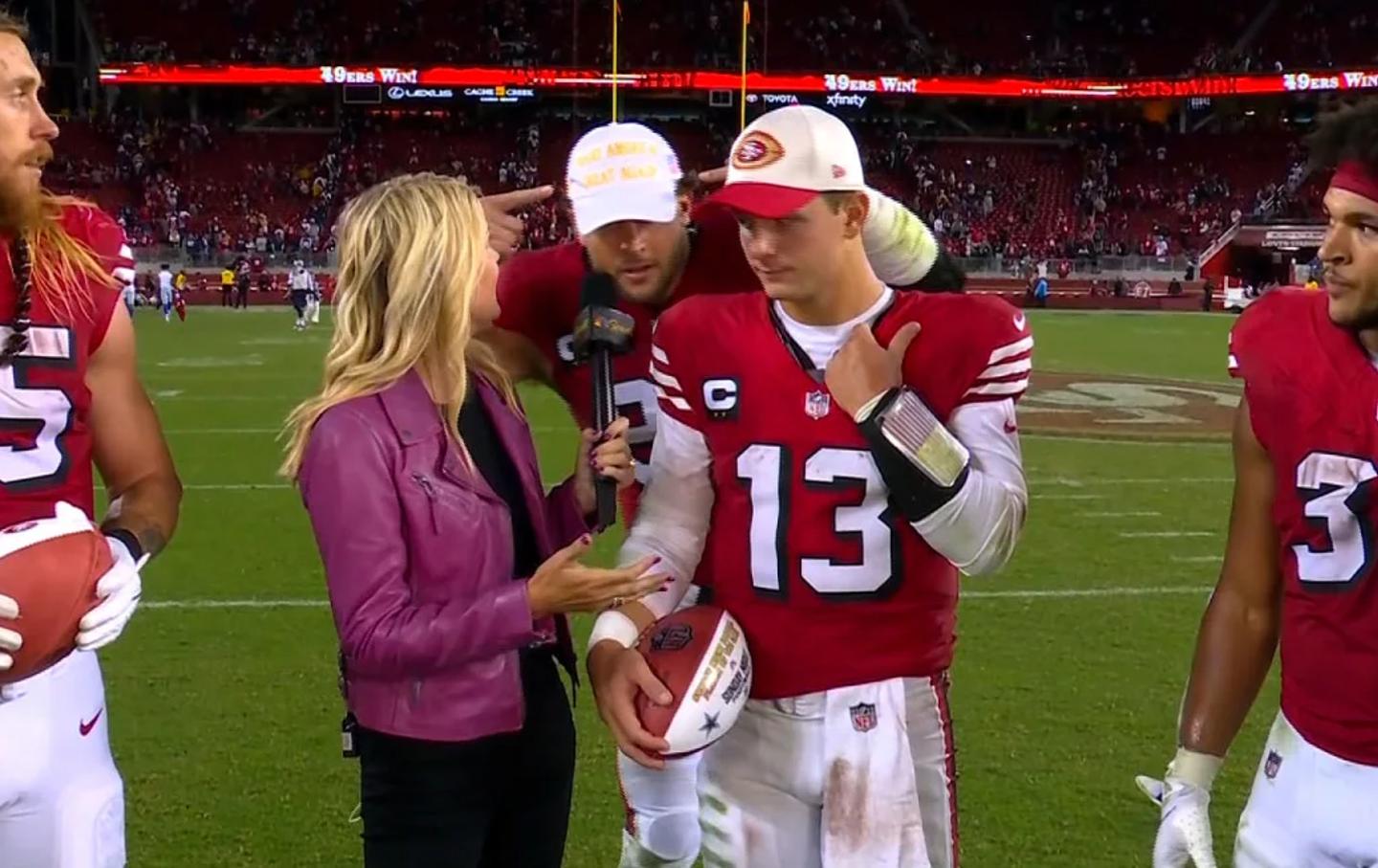

Far from the Tasmanian Devil of chaos he has been accused of being throughout his career, Irving is now a locker-room leader: the calm, elder sage on an inexperienced team whose core—including wunderkind Luka Doncic—is all of 25 years or younger. It has been especially great theater to see the prickly Doncic take to Irving like a long-lost basketball blood brother. Their energy and chemistry on and off the court is like a buddy flick from the 1980s: The cocksure Slovenian kid and a grizzled vet from New Jersey, after a wary beginning, become besotted with each other. Then they join forces to topple an evil empire of emerald green. The script writes itself.

But Irving’s metamorphosis is seen most strikingly in his relationship with the sports media. It has been stunning to watch him go from being hostile and distrustful of the press to thoughtful and gregarious. He now looks from the podium at a sea of ink-stained wretches and makes them sing his tune. They celebrate his character off the court, while belatedly recognizing his Hall of Fame skills on the court—skills that recently provoked his former teammate LeBron James to call him “the most gifted player the NBA has ever seen.”

Irving’s newfound love affair with the media is not why people are taken with him; it’s the effect. The cause is that he is no longer blithe about his own cultural power. Irving realizes that if he says—even in jest—that the earth is flat or if he retweets, apparently without having watched it, an antisemitic video, this not only distracts a whole team; it creates an image of him as some kind of villain that is at odds with reality. That negative perception was always a shame, because the common thread throughout Irving’s tumultuous career is that he gives a damn about the world. He stood with the Black Lives Matter movement almost a decade ago, after the 2014 police killing of Eric Garner, when he wore an “I Can’t Breathe” shirt to warm-ups. He embraced his Indigenous heritage and the struggle at Standing Rock. He has always been in solidarity with the people of Palestine. Irving’s mistake was thinking that his ongoing actions would define his character, when in our ravenous world of sports social media, a wrongheaded click can matter more than a decade of good work.

Kyrie Irving is in many respects still the same Kyrie, but he now sees his own power as a personality. He realizes that if he wants people to care about Black lives or Standing Rock or Palestine, how he presents those ideas are as important as how he presents himself. It’s the oldest story in sports media: either give the 24-hour news cycle something to feed upon, or they will feed on you. Irving is clearly worn out from being fed upon. He is wise enough in his 32-year-old dotage to know that if he gives of himself to the press, they will run with the narrative that this is a “new Kyrie” and will burnish his image for him.

There is nothing the media loves more than a comeback. Now, he is someone who takes a keffiyeh to press conferences and wears a Palestine-shaped pendant, yet by the time the interviews end, the hard-bitten scribes come out singing his praises. It is a dizzying feat, and it signals the greatest change in Irving: going from someone who was being played by the media—held up unfairly as a symbol for all that’s wrong with sports—to someone who now expertly plays them. Irving has always deserved his due. To see him get it is to see the inverse of a depressing truism: Irving could have left the NBA a villain, but he has lived long enough to become a hero.

We cannot back down

We now confront a second Trump presidency.

There’s not a moment to lose. We must harness our fears, our grief, and yes, our anger, to resist the dangerous policies Donald Trump will unleash on our country. We rededicate ourselves to our role as journalists and writers of principle and conscience.

Today, we also steel ourselves for the fight ahead. It will demand a fearless spirit, an informed mind, wise analysis, and humane resistance. We face the enactment of Project 2025, a far-right supreme court, political authoritarianism, increasing inequality and record homelessness, a looming climate crisis, and conflicts abroad. The Nation will expose and propose, nurture investigative reporting, and stand together as a community to keep hope and possibility alive. The Nation’s work will continue—as it has in good and not-so-good times—to develop alternative ideas and visions, to deepen our mission of truth-telling and deep reporting, and to further solidarity in a nation divided.

Armed with a remarkable 160 years of bold, independent journalism, our mandate today remains the same as when abolitionists first founded The Nation—to uphold the principles of democracy and freedom, serve as a beacon through the darkest days of resistance, and to envision and struggle for a brighter future.

The day is dark, the forces arrayed are tenacious, but as the late Nation editorial board member Toni Morrison wrote “No! This is precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.”

I urge you to stand with The Nation and donate today.

Onwards,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation