A Virtual Roll-Call Vote Will Do Severe Harm to Democratic Prospects

The Democrats can’t afford to make their Chicago gathering an inflated press conference. It must have substance—starting with an actual roll-call vote.

US Vice President Kamala Harris and President Joe Biden in the Roosevelt Room of the White House in Washington, DC, on Sunday, July 14, 2024.

(Photographer: Bonnie Cash / UPI / Bloomberg)

Milwaukee—While Republican Party leaders are stage-managing the first major-party convention of the summer in Milwaukee this week, their rivals are plotting to suck the life out of next month’s Democratic National Convention in Chicago—in what critics decry as a transparent effort to shut down debate about whether Joe Biden should be the party’s nominee.

If these Democratic insiders succeed, they will damage their party’s prospects in the fall competition with Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump, and they could potentially undermine the rest of the party ticket in a challenging election year.

At issue is the question of whether the Democrats will hold a traditional roll-call vote when they convene in Chicago from August 19 to 22. If and when that roll call is held, President Biden is likely to win it—provided, of course, that he chooses to continue as a candidate. Biden swept the party’s caucuses and primaries, winning 56 contests and an estimated 3,905 of 3,949 delegates, so he’s got the clear advantage. Unfortunately, Democratic National Committee chair Jamie Harrison and his allies, agitated by discussions about whether Biden should be replaced as the party nominee, are angling to hold a “virtual roll-call”—essentially a low-profile Zoom meeting or conference call—weeks before the convention in order to lock things in for the president. The vote could take place as soon as the first week of August, forcing a decision to be made even as Democrats remain painfully divided over whether Biden should be their standard-bearer. That fact was highlighted anew Wednesday, when US Representative Adam Schiff, a close ally of former House speaker Nancy Pelosi, and the Democratic nominee for California’s open US Senate seat, pleaded for Biden—who on Wednesday afternoon tested positive for Covid-19—to quit the race and “secure his legacy of leadership by allowing us to defeat Donald Trump in the upcoming election.”

At the same time, there were reports that Senate majority leader Chuck Schumer and House Democratic leader Hakeem Jeffries had encouraged DNC leaders to delay plans for a virtual vote to renominate Biden for at least a week.

No matter what the timing, a virtual roll-call is a terrible idea. It smacks of insider politicking and backroom dealmaking. Worst of all, it makes the party look weak, and afraid of its own base, at a time when Democrats desperately need to project strength.

Warning that the virtual roll call “will be rightly perceived as a purely political maneuver” and “could deeply undermine the morale and unity of Democrats—from delegates, volunteers, grassroots organizers, and donors to ordinary voters—at the worst possible time,” Californian US Representative Jared Huffman and several other Democratic members of Congress—with varying views on whether Biden should continue his candidacy—have been circulating a letter in which they “respectfully but emphatically request that you cancel any plans for an accelerated ‘virtual roll call’ and further refrain from any extraordinary procedures that could be perceived as curtailing legitimate debate or attempting to force an early resolution of the party nomination.”

The idea of holding a virtual roll call first surfaced two months ago, when there were concerns that an Ohio law requiring political parties to certify their presidential nominees by August 7 might block a Democratic ticket nominated after that date from gaining a place on the state’s ballot. But Ohio resolved that issue by extending the deadline to September 1. Instead of recognizing that the problem has been averted, DNC leaders and Biden campaign operatives have continued to push for a virtual vote long before the convention. In some cases, they have suggested that they want to do so because they don’t trust Ohio Republicans to maintain the extended deadline. That’s an absurd excuse; even in these hyper-partisan times, it is exceptionally unlikely that a court would permit a bait-and-switch scheme to deny Ohio voters a choice between the presidential candidates of the two major parties.

The congressional draft letter calling for the abandonment of the virtual roll-call scheme argues that “there is no serious threat to the Democratic ticket nominated in regular order at next month’s DNC convention appearing on the ballot in Ohio or any other state.” With that in mind, the House members explain that there is “no longer any legal reason for moving forward with the extraordinary step of an early nomination by way of a ‘virtual roll call.’”

It’s obvious what the virtual roll call is really intended to do: forcibly end the simmering debate over the president’s future. Biden’s claim on the nomination grew more tenuous after a miserable performance in the June 27 debate with Trump, along with several other missteps. He’s faced public calls for him to stand down from roughly 20 Democratic members of the House and Senate, the editorial pages of The New York Times and The Washington Post, actor George Clooney, and an energetic activist group, Pass the Torch, Joe! Polls also show that a majority of Democratic voters would prefer another nominee. That’s one of the reasons behind-the-scenes efforts have been waged by some party elders and donors to get the president to reconsider his reelection run.

But Biden has made it clear that he doesn’t want to stand down and, as of now, he has Democratic Party chair Harrison, many members of the Democratic National Committee, organized labor and a good cross section of centrist and progressive members of Congress—including US Senator Bernie Sanders and US Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez—in his corner.

No matter what Democrats think about the president’s continued candidacy, however, there should be a recognition at this point that making Biden the Democratic nominee before anyone shows up in Chicago raises a practical question: Why even hold what is, after all, a nominating convention, if the ticket has already been nominated?

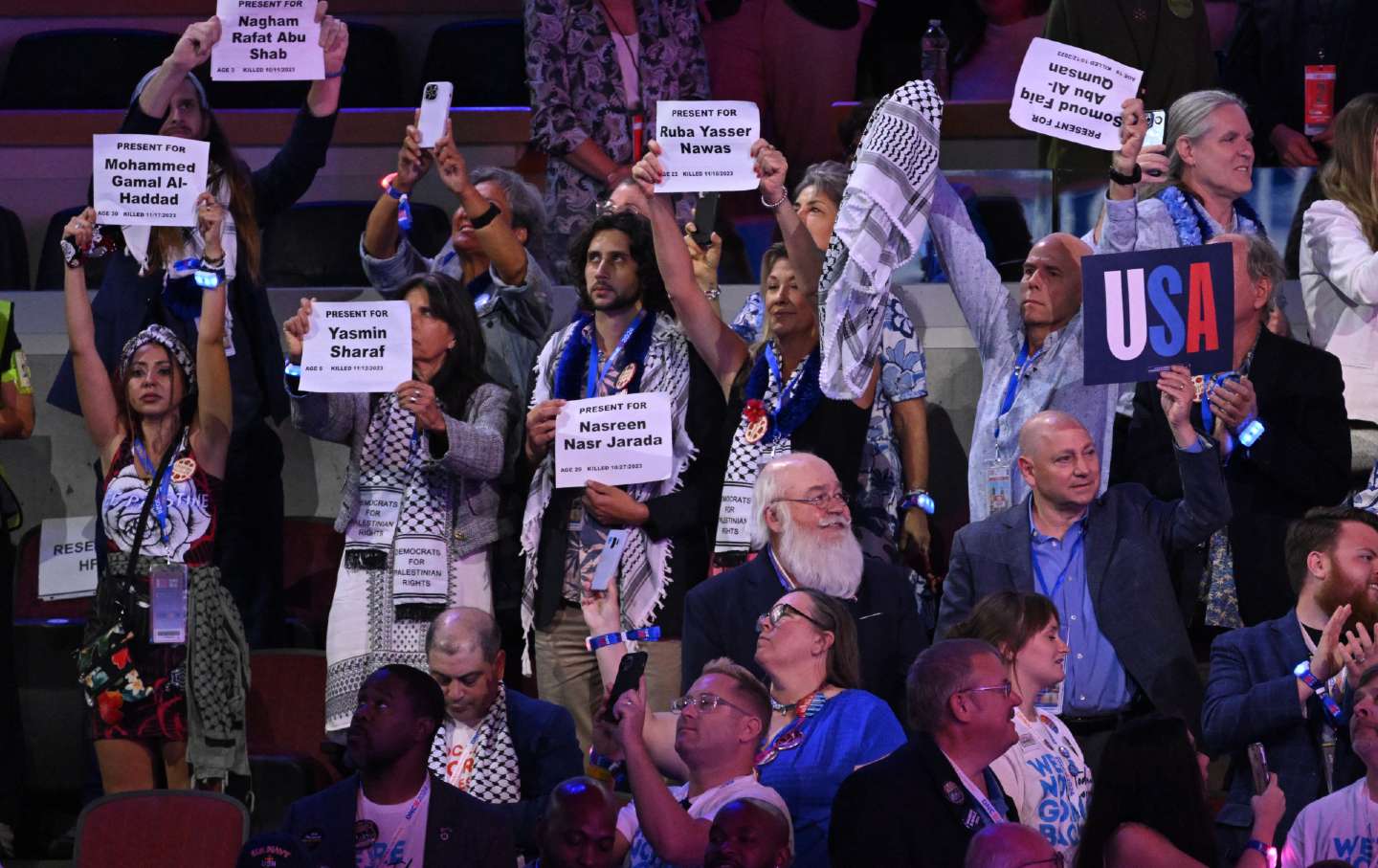

To be sure, there are Democrats who will argue that the form the roll call takes doesn’t matter. Officially, at least, nothing’s really up for grabs. Biden’s only formal opposition at this point comes from the roughly 35 uncommitted delegates from states where substantial numbers of voters wanted to register opposition to the president’s response to the Israeli assault on Gaza.

But the delegate numbers do not give a full picture of the divisions and concerns that exist within the party—regarding Biden’s viability and the question of where the party will stand on Gaza and other issues.

Sweeping those differences under the rug won’t help Biden. Addressing them could.

For that to happen, however, the DNC must, to the greatest extent possible, respect the processes that are associated with a national convention and encourage the heightened levels of engagement and excitement that extend from freewheeling live debates about what a party and its nominee should stand for.

Democrats don’t need a press conference on steroids, with speaker after speaker repeating talking points from the podium. The Republicans are already giving America one of those.

Democrats need to hold a genuine convention, with a reasonable airing of differences and sincere wrestling over issues and strategies. A debate, even a stilted one where most of the cards are in the hands of the Biden campaign, has the potential to get the president out of his comfort zone. It could also produce some genuine excitement, and that’s a commodity this party needs going into the fall.

Despite his bad debate performance and heightened sympathy for Trump following Saturday’s failed assassination attempt on the former president, polls continue to point to a reasonably close contest—nationally and in key battleground states. Biden and his aides seem to believe that their circumstance will improve as time brings clarity to the race. But that’s always been a dangerous bet.

Democrats, whether they are running Biden or someone else in November, need all the energy and enthusiasm they can generate. And that won’t come from a virtual roll-call vote or a convention that is little more than an extended “Biden for president” ad. Democrats won’t benefit from an over-managed convention this year. They need to open up avenues for the expression of dissent, regarding the nomination and the platform on which the eventual nominee will run. Even if Biden is overwhelmingly renominated, the president’s allies must understand that many Democrats disagree with Biden’s position on Gaza and fear that the party lacks a coherent message on an economy that most Americans are unhappy with.

The Biden camp will argue that the president is not getting the credit he is due for policies that have pulled the country out of Trump’s Covid-era downturn. That may be true, but there is a danger in telling Americans they “don’t know how good they’ve got it.” There must be a recognition of economic uncertainty, precarity, and frustration. And that requires an exploration of policies that spell out—clearly and unequivocally—what a second Biden administration, with a Democratic Congress, would seek to accomplish.

The best place for that exploration is in an open and honest platform-writing process, with the presentation of majority and minority reports, and floor debates on issues where real differences exist. Airing those differences is not a sign of weakness. It is a sign of strength. And Democrats should show that strength at their convention.

I’m not naïve. I know that the Biden camp will be disinclined to allow those debates, just as they are disinclined to hold a traditional roll-call vote for the presidential nomination. But Biden and his aides should abandon their caution, not merely because it makes for a more exciting and meaningful convention, but also because Biden needs the input. Even if he secures the nomination without much of a fight, he will benefit from pressure on Gaza, from pressure on economic issues, from pressure to take a clear stand on eliminating the Senate filibuster, and so much more. Most importantly, Biden is facing an electorate that, in polling, has expressed significant doubts about whether he has what it takes to serve for four more years. Shutting down debate and trying to jam his nomination through will only stir speculation that he doesn’t even trust his party’s most fervent supporters to stick with him until the convention.

There’s precedent for opening things up at a Democratic convention that Biden should consider. In 1948, President Harry Truman looked to be headed for overwhelming defeat. The polls were terrible. The Republicans had united behind a high-profile nominee—New York Governor Thomas Dewey—who was known nationally from a bid for the presidency just four years earlier. Democrats were divided, having failed to get over the loss of the unifying figure that was former President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. As the convention approached, there was a significant effort to replace Truman as the nominee, although it ultimately fizzled.

At the same time, there was a fight over the platform that Truman would run on.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The deepest divide was on the issue of civil rights—an area where many liberal Democrats thought Truman had done too little, while many Southern segregationist Democrats thought he had done too much. Instead of avoiding the issue, the party held a robust platform debate, in which 37-year-old Minnesota US Senate candidate Hubert Humphrey famously called on the convention to “get out of the shadow of states’ rights and walk forthrightly into the bright sunshine of human rights.”

The delegates faced pressure from Southerners who opposed civil rights and Truman aides who thought that taking a bold stand against discrimination, segregation, and barriers to voting rights would divide the party and lose the support of what was then described as the Democratic Party’s “solid South.” In the end, they voted 651½-582½ in favor of the bold civil rights plank that Humphrey—and activists such as Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters leader A. Philip Randolph—said was both morally and politically necessary. Many Southern Dixiecrats bolted. But Truman was able to unite the party outside the South and, with a strong boost from Black voters in the rapidly industrializing cities of a number of swing states, he surprised the pundits and won reelection by a commanding margin. So commanding that Democrats picked up 75 seats in the House and nine seats in the Senate, a result that allowed the party to regain full control of the Congress.

The convention debate that Truman and his aides initially feared played an important role in turning around the fortunes of an embattled campaign. That’s a lesson Biden and Democrats should look to as they consider just how open, honest, and exciting they want the 2024 Democratic National Convention to be.

Can we count on you?

In the coming election, the fate of our democracy and fundamental civil rights are on the ballot. The conservative architects of Project 2025 are scheming to institutionalize Donald Trump’s authoritarian vision across all levels of government if he should win.

We’ve already seen events that fill us with both dread and cautious optimism—throughout it all, The Nation has been a bulwark against misinformation and an advocate for bold, principled perspectives. Our dedicated writers have sat down with Kamala Harris and Bernie Sanders for interviews, unpacked the shallow right-wing populist appeals of J.D. Vance, and debated the pathway for a Democratic victory in November.

Stories like these and the one you just read are vital at this critical juncture in our country’s history. Now more than ever, we need clear-eyed and deeply reported independent journalism to make sense of the headlines and sort fact from fiction. Donate today and join our 160-year legacy of speaking truth to power and uplifting the voices of grassroots advocates.

Throughout 2024 and what is likely the defining election of our lifetimes, we need your support to continue publishing the insightful journalism you rely on.

Thank you,

The Editors of The Nation

More from The Nation

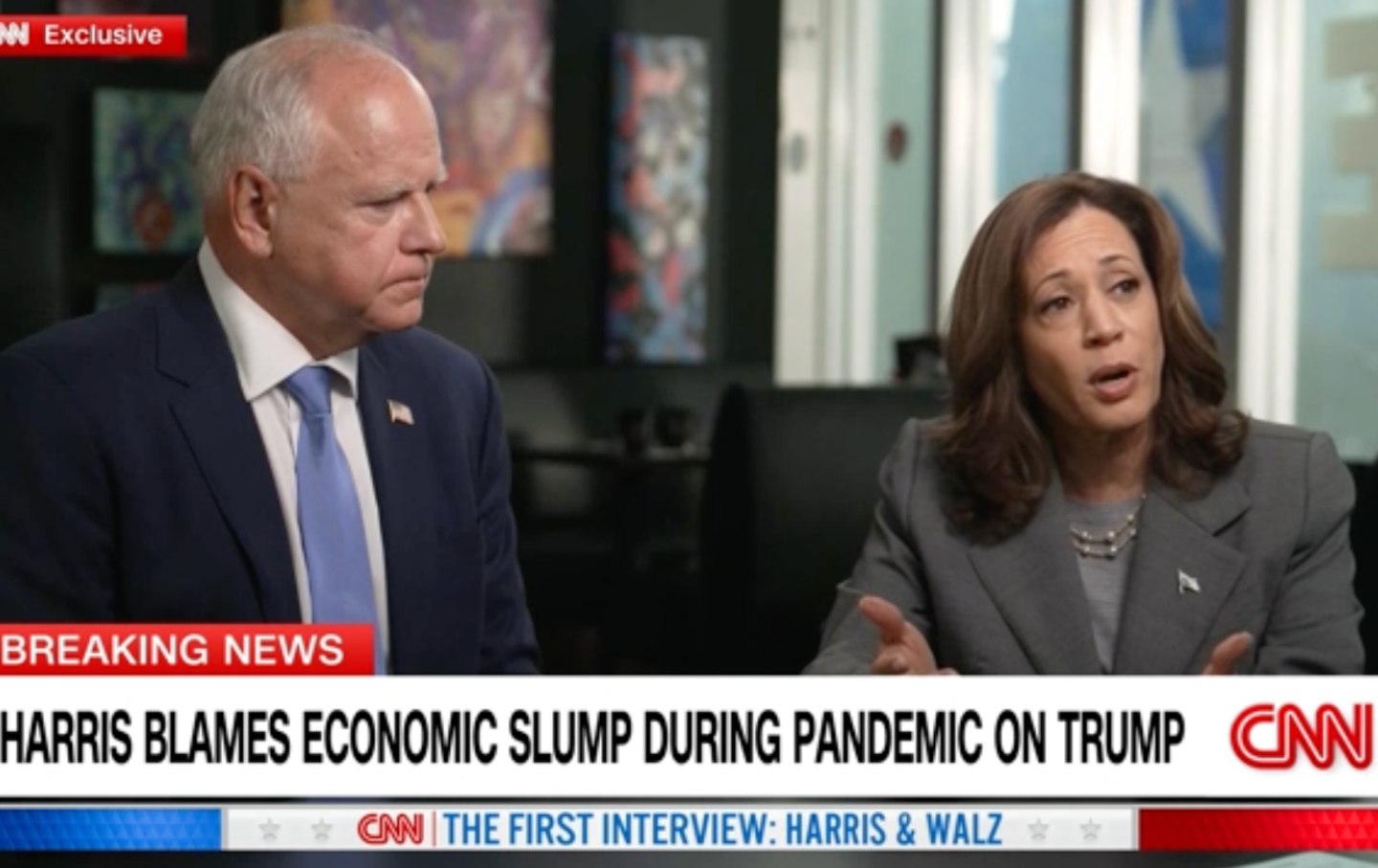

The Beltway Media Got Its Harris Interview. Can We Move on Now? The Beltway Media Got Its Harris Interview. Can We Move on Now?

Harris and Walz held their own during an interview driven more by media-made controversies than substance.

I’m Still Hoping to Vote for Kamala Harris I’m Still Hoping to Vote for Kamala Harris

But the hope I felt when she became the nominee has been curdling into despair over her refusal to allow a Palestinian to address the convention—and her continuing silence on Gaza...

Don’t Underestimate Donald Trump’s Coalition of the Weird Don’t Underestimate Donald Trump’s Coalition of the Weird

The GOP’s new league of fringe figures tries to replicate the party’s winning formula of 2016. And it just might work again.

It’s Not Too Early to Ask: Who Should Replace Merrick Garland? It’s Not Too Early to Ask: Who Should Replace Merrick Garland?

Should Kamala Harris win in November, her attorney general pick will be among her most critical cabinet appointments. Progressives should start organizing now.

The Backlash Comes for Oakland’s Progressive Prosecutor The Backlash Comes for Oakland’s Progressive Prosecutor

Pamela Price, the Alameda County DA, is fighting a recall vote and to defend her unwavering refusal to over-criminalize young people.

Youth Voter Turnout in NYC Is Struggling. These Organizations Want to Fix It. Youth Voter Turnout in NYC Is Struggling. These Organizations Want to Fix It.

A lack of knowledge about the process—from registration to marking a ballot—is often the main barrier between youth and voting. “If young people sit it out, that will have an impa...