The Brooklyn Potluck That Helped Black Literature Flourish

In Courtney Thorsson’s cultural history The Sisterhood, she details how intimate gatherings played a role in the golden age of Black women’s writing.

Brooklyn, 1974.

(Photo by HUM Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

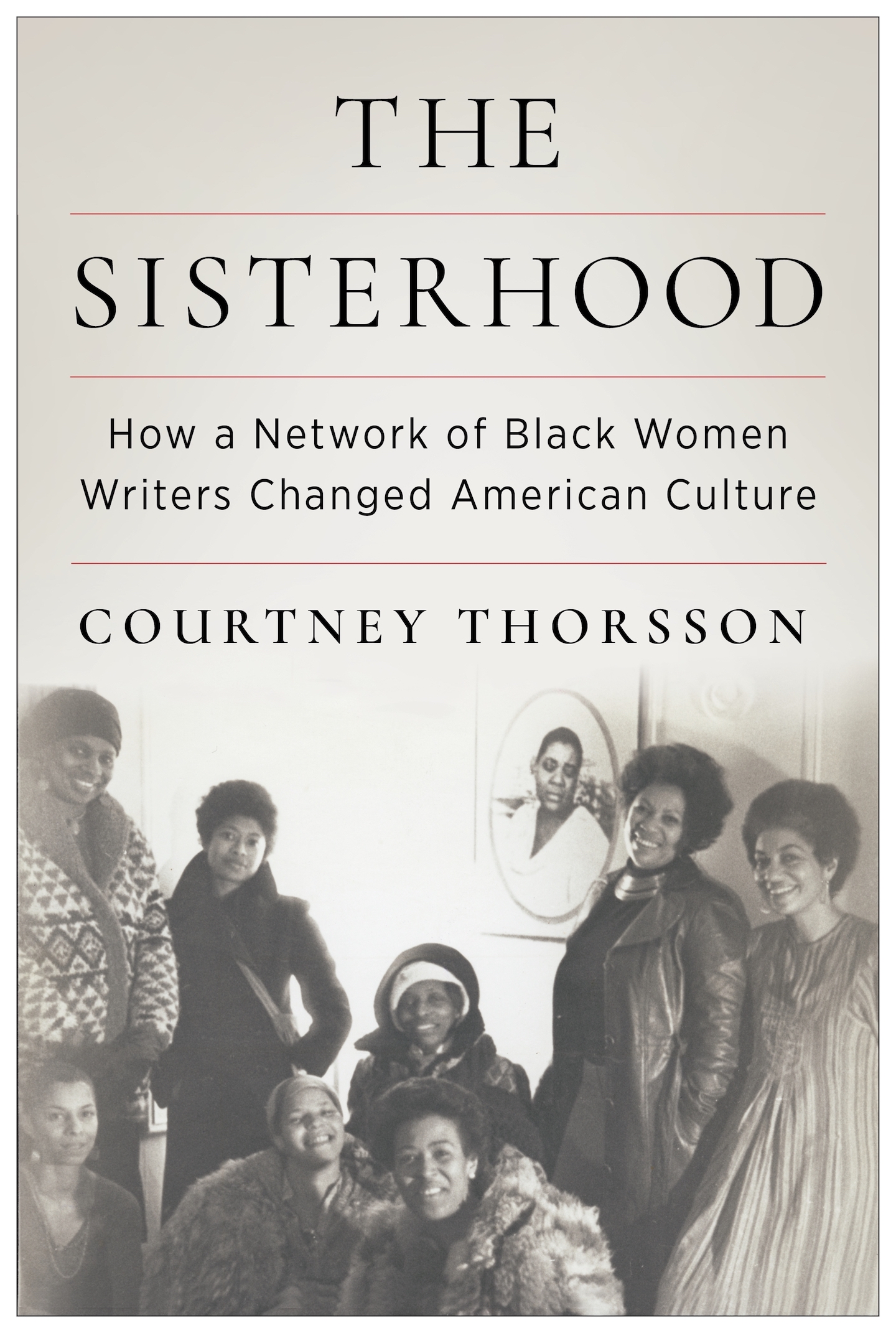

In February of 1977, eight Black women gathered for a photograph in a Brooklyn apartment. There are some faces that you might recognize: novelists Toni Morrison and Alice Walker, poet June Jordan, and playwright Ntozake Shange. And there are some faces that most people today would not, women whose work is forgotten or little-known: food writer Vertamae Grosvenor, Black feminist writer Lori Sharpe, meditation instructor Nana Maynard, and journalist Audreen Ballard. The photo was taken in the living room of Jordan’s Park Slope apartment and seemed to fulfill the desire for refuge she speaks of in her 1982 poem “Moving Towards Home”: “I need to speak about living room / Where the talk will take place in my language.” Despite the historical significance of this group of Black women, gathered in an intimate space to discuss important matters of life and liberation, their winter coats suggest that the photo was an afterthought, secondary in importance to the richness of their conversation.

Books in review

The Sisterhood: How a Network of Black Women Writers Changed American Culture

Buy this bookThe photograph brings up tantalizing questions about the social group these women formed, a group they called the Sisterhood. What did they talk about among themselves, what did they share in their meetings? Might Alice have arrived before the meeting to tell her friend June something crucial and heartbreaking about her own love life? Might Toni have encouraged Ntozake to write a novel, because that’s where the money was? Might Vertamae have cooked something delicious—a pot of hopping john or a pound cake—from her 1970 book Vibration Cooking?

In The Sisterhood: How a Network of Black Women Writers Changed American Culture, Courtney Thorsson captures some of the ineffable nature of this gathering of Black women writers and artists, which met on the third Sunday of every month for two years, from early 1977 to early 1979. After the first meeting in Jordan’s home on February 6, 1977, the Sisterhood grew to include up to 30 known members. According to an early agenda from February 20, 1977, the group decided that “refreshments will be ‘pot luck’ and sisters should feel free to bring other ‘favorite things’—records, poems, etc.” Despite the casual setting and ad hoc agenda, Thorsson makes a direct link between the Sisterhood’s meetings and the impressive array of publications by its members in the following decade, including Jordan’s Passion (1980) and Civil Wars (1981); Walker’s The Color Purple (1982); Paule Marshall’s Praisesong for the Widow (1983); Shange’s Sassafrass, Cypress & Indigo (1983); Audre Lorde’s Zami (1982) and Sister Outsider (1984); and Morrison’s Tar Baby (1981) and Beloved (1987). Thorsson’s book—which tells the story of the group through a careful consideration of Black women’s work in the publishing industry and academia from the 1970s to the present—proposes that the Sisterhood played a key role in the intellectual production of this golden age of Black women’s writing. Indeed, the friendships of the Black women in the Sisterhood were crucial to their careers, in fulfillment of another Jordan maxim: “We are the ones we have been waiting for.”

Thorsson’s tremendous archival research is paired with interviews, close readings of the Sisterhood’s published works, and an in-depth literary history of publication outlets in the 1970s and ’80s. According to Thorsson, novels, plays, and poetry were the fruit and flowers of “the unglamorous work of making the places one inhabited every day—homes, offices, classrooms—less racist, sexist, and homophobic.” Especially significant was the Sisterhood’s mark on Essence and Ms. magazine, through Walker, Ballard, and Judith Wilson, who served on the editorial boards of those publications. In these mainstream periodicals, Thorsson argues, “the Sisterhood pushed the publication of serious, sometimes politically radical Black feminist writing.” Though Walker eventually resigned from the editorial board of Ms. because of its tokenization of her status as a Black woman, her canonical 1974 essay “Looking for Zora” was published in the magazine during her tenure, as well as reviews of works by Jordan and Toni Cade Bambara, and an excerpt from Michelle Wallace’s then-controversial Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (a 1978 work critiquing misogyny in 1960s and ’70s Black liberation movements, which many perceived to be an unfair attack on Black men).

In their efforts to work within preexisting publication channels, the Sisterhood might have differed from more formalized Black feminist organizational spaces of the era. Thorsson notes that “consciousness-raising groups of the 1960s and ’70s were devoted to study and were often explicitly anticapitalist; the Sisterhood used those tools to different ends by engaging in professional networking (creating a ‘Rolodex’) and participating in a capitalist marketplace (planning to incorporate and seeking ‘investors’).” This likely might have been in tension with the leftist politics of some of the group’s individual members, including Walker and Jordan. In fact, Jordan had to be reminded that the group was meant for “black women who are artists or artist-related,” and had to be dissuaded from using its resources to establish “a center for battered black women.”

However, Thorsson writes that the members did not make a sharp distinction between politics and aesthetics, and that “for the Sisterhood the work of recovery and publication was political.” They proposed, for instance, starting a magazine that would publish contemporary Black writers but also survivalist “information about and pertaining to the provision of food, clothing, and shelter,” and they also hoped to start a publishing house that would “‘re-issue out-of-print black books,’ ‘anthologize important black articles,’ and possibly establish a ‘distribution relationship with Random House’ with Morrison’s help.” Though the proposed magazine (with its offerings of material resources for the Black masses) and the publishing house never materialized, many of the Sisterhood’s literary goals were achieved by other means. Walker, for instance, was key to the reissue of Zora Neale Hurston’s out-of-print works in the 1970s, and Vèvè Clark anthologized the writings of Hurston’s important contemporary Katherine Dunham. And in her editorial role at Random House, Morrison famously edited and advocated for the works of now-canonical Black writers like Angela Davis, Gayl Jones, Lucille Clifton, and Bambara. If the forces that had historically doomed Black women writers to poverty and obscurity were political, so too were the Sisterhood’s efforts to keep the living out of poverty and the dead out of obscurity.

The Sisterhood learned from the Black Arts Movement “to demand and create spaces—classrooms, editorial meetings, academic journals, book reviews, and anthologies—where Black writing was understood on its terms.” The group began with this impetus to create its own press or publication that would treat Black ideas with dignity and respect, but ultimately it fell victim to the success of its most famous members, whose creative endeavors left them with little time to build Black-led outlets from the ground up. Instead, they focused more diffusely on reforming the existing publishing industry and the university, vexed institutions that nevertheless offered them steady employment. As editors and academics, they played a key role in establishing Black feminism as a field of study that would later be co-opted by their workplaces into a neoliberal framework of diversity, equity, and inclusion. As Thorsson points out, Black women’s labor in these institutions “was not wholly radical or assimilationist and it was not entirely subversive or hegemonic; it was simultaneously all of these.” For better or worse, these contradictions plague Black women writers to this day.

Though its lofty goal “to use literature for Black women’s liberation” might not have manifested in the creation of new institutions, the Sisterhood played a notable role as an emotional refuge for Black women writers in an era of misogynistic scrutiny. Walker and Shange, along with Michelle Wallace (who attended only one meeting of the Sisterhood and then declined to take part further in the group), were subjected to a virulent misogynoir backlash that labeled them as man-haters and profiteers, causing Shange to consider hiring bodyguards. The public vitriol directed at these young Black women—enabled by prominent Black male writers like Ishmael Reed, Robert Staples, and Askia Touré—demonstrates the kind of intra-racial violence against Black women that they were critiquing in their writing. If the “Black gender debate” of the 1970s provided a forum for Black men to attack Black women’s perspectives on their own gender oppression, groups like the Sisterhood were crucial in providing spaces where Black women’s humanity was not up for debate. According to Sisterhood member Judith Wilson, the group was not initially conceived as a “place for ‘networking’ and ‘professional’ advancement, but rather as a form of ‘psychological support’ that came from the ‘experience of seeing that there were so many of us.’” In that more modest goal, it appears that the Sisterhood succeeded.

Thorsson also offers a humane depiction of some of the Sisterhood’s shortcomings. Theologian Renita Weems, a younger member who served as secretary for the group, told Thorsson in an interview that after a while, “the name-brand people who were at the core of it…no longer prioritized coming.” As their profiles grew, it seems, some of the more famous members became too busy to attend meetings and left the secretarial labor of running the group to younger or less established members like Weems. Interviews like this are an important part of Thorsson’s effort to reinscribe the Sisterhood’s breakout stars—so often exceptionalized by the American literary establishment—within a larger community of Black women who nourished, supported, and informed them. Without excusing the unfair division of labor that left the less illustrious members to “pick up the slack,” Thorsson does an excellent job of detailing the public scrutiny and whirlwind schedule of engagements that might have kept the more famous members exhausted and away. For example, Thorsson’s reading of Jordan’s poem “Letter to My Friend the Poet Ntozake Shange” shows both women at home briefly between transcontinental speaking engagements, with Jordan’s punch line—“maybe / one of us / better slow down!?”—serving as an ironic counterpoint to their perceived success.

The Sisterhood is not without its blind spots, especially regarding Black women writers based outside New York, the center of American publishing. Thorsson describes the Sisterhood’s hierarchical nature as one of its weaknesses, but in inflating the importance of the New York literati as a singular group that “changed America,” she sometimes reproduces an equally pernicious regional hierarchy. For instance, Thorsson describes Bambara as “a kind of one-woman branch of the group in Atlanta.” But it is inaccurate to paint Bambara, who was not a member of the Sisterhood, as somehow ancillary to the New York–based group, even if she did maintain friendships and correspondence with some of its members. In Atlanta, Bambara worked with the Southern Collective of African American Writers (SCAAW), an organization whose workshops and publications were open to any self-identified Black writer, aspiring or established. Thorsson admits that SCAAW “may have been more successful in creating an antihierarchical structure” and also that it remained active much longer than the Sisterhood—for more than a decade—but she still attributes its activities to the influence of the Sisterhood. Given that Thorsson consulted Bambara’s papers at Spelman College, the elision of archival materials honoring the distinct mission of SCAAW is disappointing, because it could have provided a more nuanced view of the Sisterhood as one of multiple regional networks of support for Black writers in the 1970s.

Overall, The Sisterhood provides a fascinating glimpse into a social and intellectual network that we are still discovering but may never fully know. Due to a lack of recordkeeping during the final year of the group’s meetings, Thorsson acknowledges, the contents of its discussions remain elusive, so instead she describes moments when the afterlives of its kinship bubble to the surface, becoming briefly legible in the public discourse. Just as Morrison advocated for Jordan’s poetry collection Things That I Do in the Dark by soliciting reviews in advance of its publication in 1977, for example, so Jordan returned the favor by spearheading a 1988 open letter in The New York Times by 48 Black intellectuals to protest Morrison’s omission from the candidates for the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize. For all her literary achievements and accolades, Morrison described this open letter as “easily the most significant thing that has happened to me in my writing life.” Thorsson makes every effort to unveil these moments of community support that, for Black women then as now, make the writing life possible.