What No One Talks About When They Talk About Taiwan

In so many histories, writers so often ignore the social movements and underclass that helped define island nation’s destiny.

The view from the Taipei 101 tower, 2020.

(Photo by Carl Court / Getty Images)

There was once a time when Taiwan was referred to by international news outlets as a “self-ruled island.” A decade ago, when papers like The New York Times and The Washington Post were reporting on the 2014 Sunflower Movement—the youth-led occupation of the Taiwanese Legislature that was among the largest, if not the largest, social movement in the country’s history—it was normal to describe the island nation as such.

Books in review

The Struggle for Taiwan: A History of America, China, and the Island Caught Between

Buy this bookAt the time, this boilerplate designation never acknowledged how much Taiwan had democratized in spite of decades of US-backed authoritarian rule by the Kuomintang (KMT), in the classic mold of right-wing, anti-communist strongmen with US backing. The struggle to build democratic institutions, and the popular demonstrations that continued to hold the elected government accountable, happened even with the specter of danger that hung over Taiwan: the threat of annexation by China. This in itself contributed to the rise of the Sunflower Movement, with the KMT seen as overriding democratic institutions to defend Taiwan’s sovereignty.

Fast-forward a decade, and Taiwan is now routinely called the “most dangerous place on Earth,” as the title of a now-infamous issue of The Economist declared, and has frequent visits by American politicians as a show of support. All of these international developments, if you follow the Anglo-American press, underline the fraught nature of the island nation’s place in the world. Take, for example, then–US Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi’s 2022 visit to Taiwan, against the wishes of the Chinese government. In the aftermath of that visit, to register its displeasure at what it called an infringement of its sovereignty, China launched an unprecedented display of military exercises around the island. The Pelosi visit set the tone for subsequent US support of Taiwan.

And, of course, some of the alarm has emerged from the central role Taiwan plays in global semiconductor manufacturing: With the supply-chain shortages that the world experienced during the Covid-19 pandemic, Taiwan’s importance in the realm of consumer electronics became strikingly clear—semiconductors made in the country are key components in products as disparate as Playstations and electric cars.

To meet the challenge of discussing Taiwan’s situation, in the past several years there has been a host of new books intended for a public whose knowledge of the country hasn’t been updated much since the Cold War. One such example is Sulmaan Wasif Khan’s The Struggle for Taiwan. The approach that Khan, a professor of international history and Chinese foreign relations at Tufts University, takes as a historian is not without its merits; his reading of the dynamics of the Cold War in Asia is praiseworthy. But The Struggle for Taiwan is ultimately still a history of political leaders and elites. It fails to grasp the democracy-from-below dynamics that exist in the country and doesn’t place enough weight on the movements that helped democratize Taiwan.

Unfortunately, one can only get to know so much about Taiwan and its people through this approach, with the history flattened into the story of “great men”—an approach that tells us little about how Taiwan’s past will influence its future.

Still, Khan’s task is not an easy one: to sum up over 70 years of history while also carving out enough space to discuss the complexities of the unique circumstances that Taiwan faces in the 21st century. After all, Taiwan is the unusual case of a de facto independent nation-state with its own government, elections, economy, military, passport, and currency that lacks de jure recognition as a result of Chinese diplomatic pressure.

To this end, Khan begins his narrative shortly after the end of the Chinese Civil War. He does not dwell on the long war between the KMT and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) before the two agreed to cooperate to fight the Japanese. There is, after all, already a voluminous body of English-language histories on the Chinese Civil War, often framing a struggle that was fought across a nation of hundreds of millions as a turbulent moment of transition mediated solely through the bitter struggle between Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong. And such histories usually stop with Chiang’s exile in Taiwan, as though that were the end of the story.

But in focusing on Chiang’s decision-making in terms of the KMT’s retreat to Taiwan and his at-times-antagonistic relationship with his American backers, Khan is attentive to the way that Chiang played his part as merely the first among equals rather than the unquestioned leader of the array of forces aligned with the KMT during the Chinese Civil War. Likewise, Khan does a good job of describing how trends in American politics, such as the rising tide of anti-communism in the 1950s, came to influence the dynamics of the US-Taiwan relationship. In this, Khan manages to avoid depicting either the KMT or the United States as a monolithic political force, instead painting both sides with a great degree of nuance.

Khan is aware that the Democratic Progressive Party, which currently rules Taiwan, traces its roots to Taiwan’s democracy movement and that this movement arose from resistance to the KMT, which began almost as soon as it arrived in Taiwan. But this often comes off as cursory in Khan’s book, with only passing references to political figures from the resistance against the KMT, such as the Marxist revolutionary and Taiwanese independence activist Su Beng. Pushback against the KMT stemmed in part from the backlash against the political system that it instituted after its arrival, one that favored those descended from people who had traveled to Taiwan after the Chinese Civil War, because of their links with the party. This was a guiding principle of Su Beng and others’ calls for Taiwanese independence during this period, on the basis of the principles of self-rule.

By missing this important on-the-ground resistance, Khan proves less adept at describing Taiwan’s transition to democracy than other aspects of his story—and his biases filter through in his account of democratization. That is, one hears too many echoes in his book of the celebratory accounts of Taiwanese democratization that depict Chiang Kai-shek’s son and successor, Chiang Ching-kuo, as having hidden pro-democracy aspirations that emerged late in his life. In reality, the KMT stepped back from power because it recognized that it could not forever contain the rising tide of social dissatisfaction. The developments in the Philippines and South Korea in the 1980s and ’90s provide dramatic examples of what happened when people’s movements overturned unelected authoritarian governments.

This has been a recurring theme in many Anglophone histories of Taiwan, which credit the KMT—despite its having been the country’s authoritarian ruler—with having voluntarily relinquished its power through the apparent wisdom of its leaders. And this is partly the case, given that the KMT did realize that it would not be able to maintain control over Taiwan indefinitely through armed rule, while it could maintain political influence in steering the process of democratization.

But one still wonders why the moments of retrenchment and protest are ignored. Incidents of major protest, such as the 1979 Kaohsiung incident and the 1990 Wild Lily Movement, or outrage over the deaths of political dissidents such as the journalists Henry Liu and Cheng Nan-jung, are historically important because they show that Taiwan’s democratization did not occur solely through party politics. Rather, it was the interplay between the actions of the state and the ground-level resistance that led to Taiwan’s democratization, not the decisions of the KMT alone.

One undercurrent of Khan’s narrative of Taiwanese history is his rather inattentive approach to the sub-ethnic dynamics of the island’s politics. These sub-ethnic dynamics, as well as the political disparity between the capital of Taipei and the rest of the nation, have long been drivers of political contention on the island—significant because it shows that not all dimensions of Taiwanese politics are directly related to China’s territorial claims. The rise of Lee Teng-hui, for example, who came to the presidency through the KMT but then unexpectedly proved to have pro-independence sympathies, is not understood in Khan’s book as a compromise meant to address the sub-ethnic dynamics of Taiwanese politics, which could no longer be ignored by the 1980s and ’90s.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Lee became president in spite of the misgivings of the KMT establishment. His ascension was a compromise, given that his ethnic background was that of the benshengren—those descended from the hundreds of years of Han migration to Taiwan that preceded the KMT’s retreat to the island after the Chinese Civil War. This was due to rising discontent with the KMT’s rule, which privileged the waishengren, the descendants of those who came to Taiwan after the civil war.

Indeed, it proves difficult to understand the rise of Chen Shui-bian in the 2000s—the first victorious presidential candidate of the Democratic Progressive Party, and the first non-KMT president in Taiwanese history—without a grasp of these dynamics. Chen leaned heavily into his benshengren identity in his political messaging. At the same time, Khan provides a surprisingly sympathetic and revisionist account of his presidency, pointing to how Chen was often perceived internationally as a dangerous pro-independence provocateur; in fact, on many occasions, he sought economic rapprochement with China. This is an important dimension of the Chen administration that has been overshadowed in retrospective readings of his presidency that focus only on his critical statements—as exemplified in his advocacy of a referendum on Taiwanese independence—and fail to note the way that key DPP politicians courted China during this time.

The Struggle for Taiwan is unquestionably at its weakest when it comes to the past decade of Taiwanese politics. Here again, Khan seems strangely inattentive to social dynamics, all the more so when he discusses major political events that saw little coverage in the Anglo-American press.

Khan’s discussion of the 2014 Sunflower Movement, which broke out against a KMT that had returned to power, is instructive. The movement involved the month-long occupation of the Taiwanese Legislature by student activists protesting a trade agreement that the then-ruling Ma Ying-jeou administration hoped to sign with China, culminating in around 2 percent of the Taiwanese population converging on the streets of Taipei.

For Khan, this was merely a brief protest against the KMT government’s lack of transparency, and he positions fears regarding Taiwan’s “mainlandization” as mostly occurring in the decade after the Sunflower Movement. Quite the opposite, as fears regarding “mainlandization” took root in the years prior to the Sunflower Movement, at a time when China’s economic and political heft was on the rise, including the influx of millions of Chinese tourists during the 2010s. (Covid-19 proved the death knell of the influence on Taiwan from Chinese tourists, who were unable to come to the island afterward due to continued restrictions in both countries.)

Khan is unable to balance all the moving pieces of his narrative, leading to some strange omissions. It proves somewhat abrupt when he finally introduces the debate about extending the military draft in Taiwan close to the end of his book, with regard to long-standing questions about Taiwan’s military capabilities and how it might deter a Chinese invasion. But the draft had long been a rite of passage in society for young men. And the threat of a Chinese invasion has been the sword of Damocles that has hung over Taiwan for decades. The threat from China is not new and has long influenced domestic politics—the KMT, for example, maintained its political control over Taiwan using emergency measures passed under the auspices of fighting communism, leading to what was once the world’s longest period of martial law.

Indeed, the irony of Taiwan’s democratization is that the KMT could only maintain power for so many decades because of US backing. China’s claims over Taiwan mostly followed those of the KMT, with the CCP taking little interest in the island before that. In this sense, tensions over Taiwan are not only the product of the legacy of the Chinese Civil War but the unresolved legacy of how the US propped up the Chiang regime. Consequently, Taiwan has long been a proxy for the tensions between the US and China, not just in the last few years.

In many ways, then, Western perceptions are playing catch-up in light of the sudden attention on Taiwan since the Covid-19 pandemic and the 2022 Pelosi visit. Though The Struggle for Taiwan has its merits, it can still be situated as a book that emerges from this attempt to update understandings of the country. Yet understanding the dynamics of Taiwanese society requires a grasp of how the history of people’s movements cemented democracy there, rather than simply asserting that Taiwan was lucky enough to have a series of wise leaders—a particularly ironic view considering that Taiwan’s democracy is still relatively recent, and a number of its leaders were unelected autocrats. After all, Taiwan’s past can provide little insight into its future if its history is viewed exclusively as that of its political elite rather than of its people, when it is the people of Taiwan who will ultimately determine its future.

More from The Nation

The Misunderstood Vision of KAWS The Misunderstood Vision of KAWS

An exhibition of his impressive collection compels our art critic to ask if we should start taking the world famous street artist’s project more seriously.

Novelist on a Deadline: Barry Malzberg, 1939–2024 Novelist on a Deadline: Barry Malzberg, 1939–2024

A speed demon at the typewriter, Malzberg wrote quickly and brilliantly in a variety of genres including mystery, thrillers, and erotica, but his core work was in science fiction....

The Best Albums of 2024 The Best Albums of 2024

This year’s best music, our critic thinks, defied conventions of genre and doctrine, showing how hybrid and fluid the art has become.

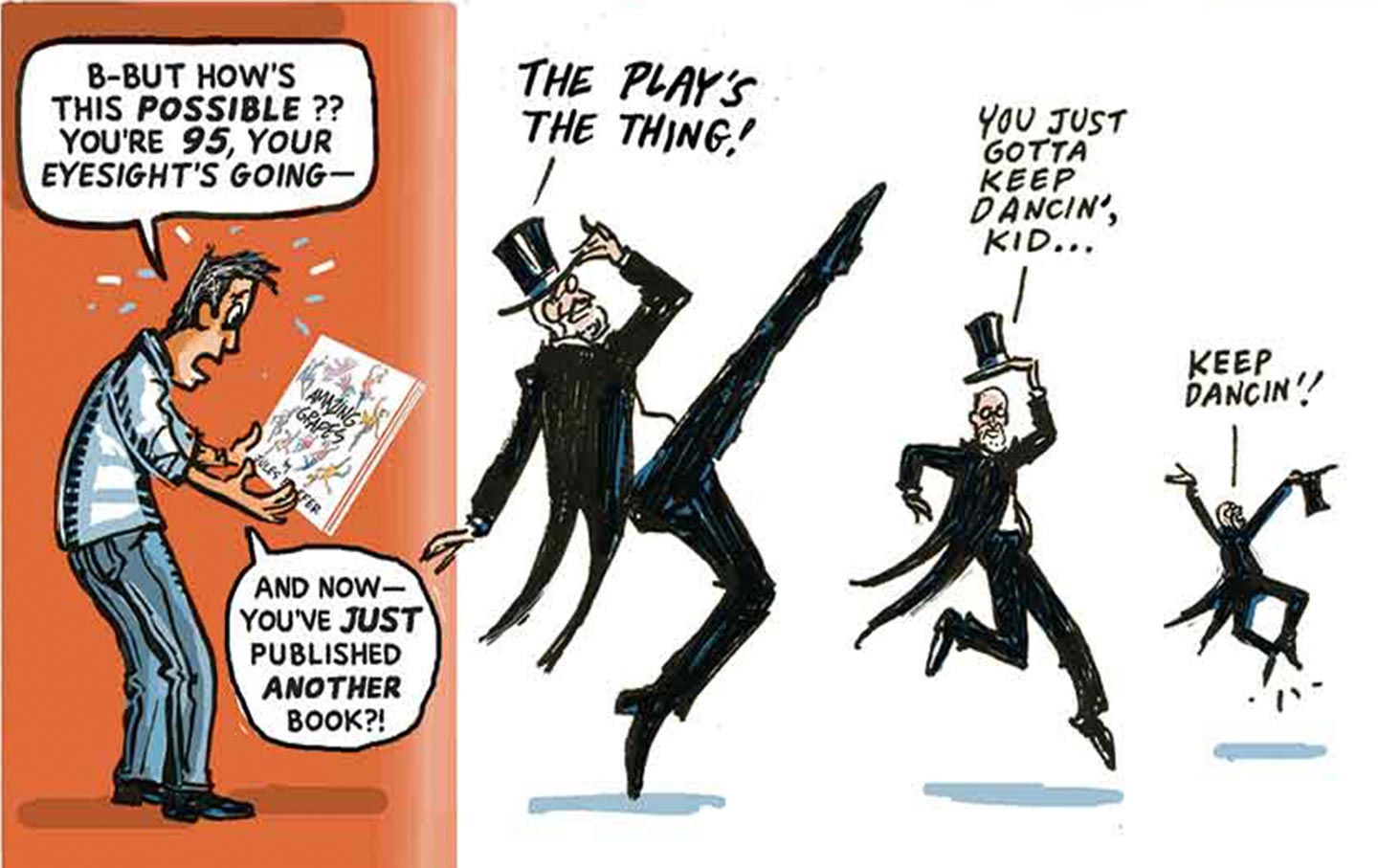

A Dance to Jules Feiffer at 95 A Dance to Jules Feiffer at 95

Cartoonist and writer Jules Feiffer is a national treasure. To mark his 95th birthday, we had some questions for the longtime Nation contributor.

The Empty Thrills of Alfonso Cuarón’s “Disclaimer” The Empty Thrills of Alfonso Cuarón’s “Disclaimer”

Why did the great Mexican filmmaker make a soapy thriller?

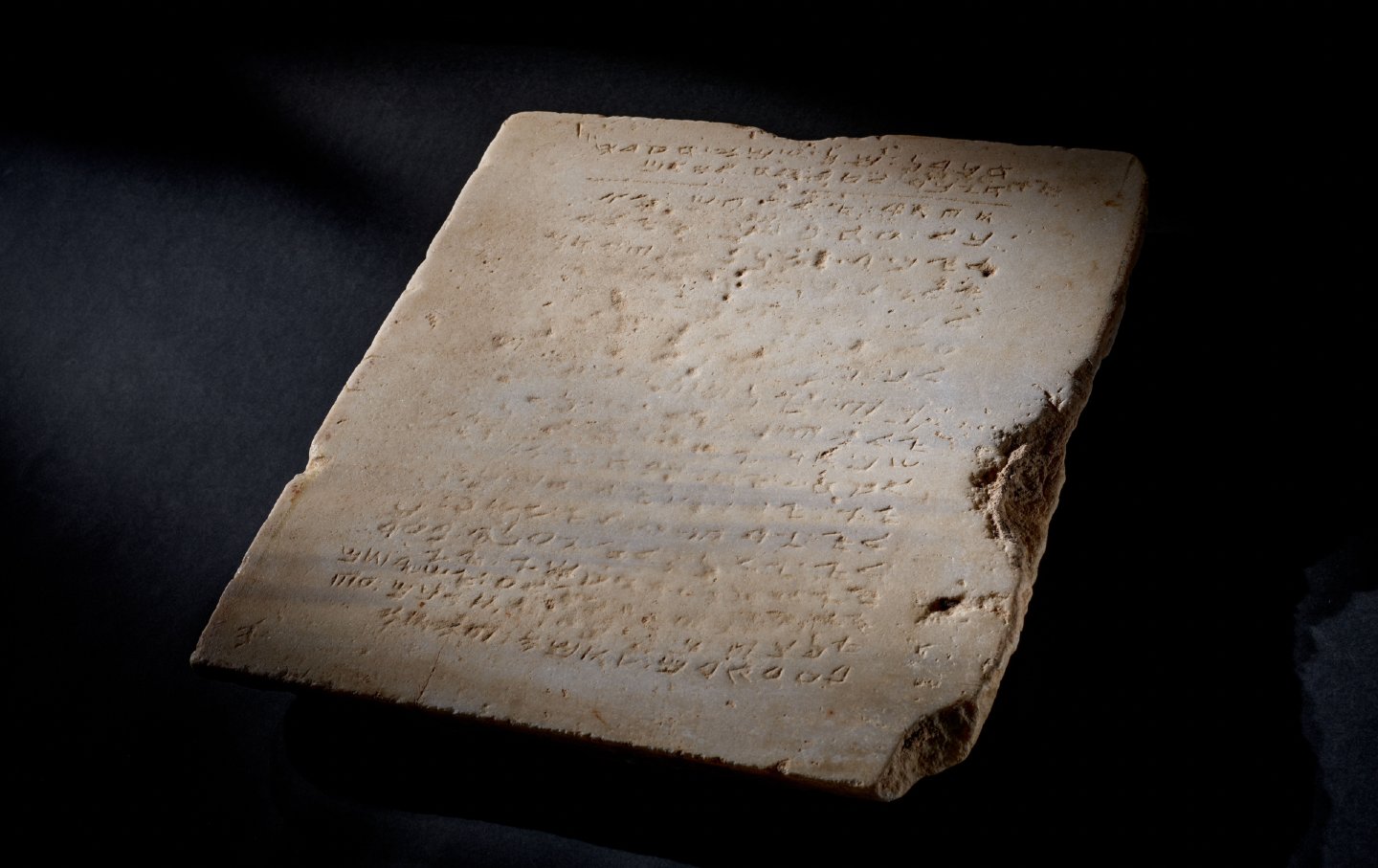

Auctioning Off Judaism’s Past Auctioning Off Judaism’s Past

As the collections of Sir Moses Montefiore and David Solomon Sassoon go under the hammer today, what's the future for rare books and historic artifacts in the age of generative AI...