Every Schoolchild Should Eat Free

Full bellies lead to attentive minds.

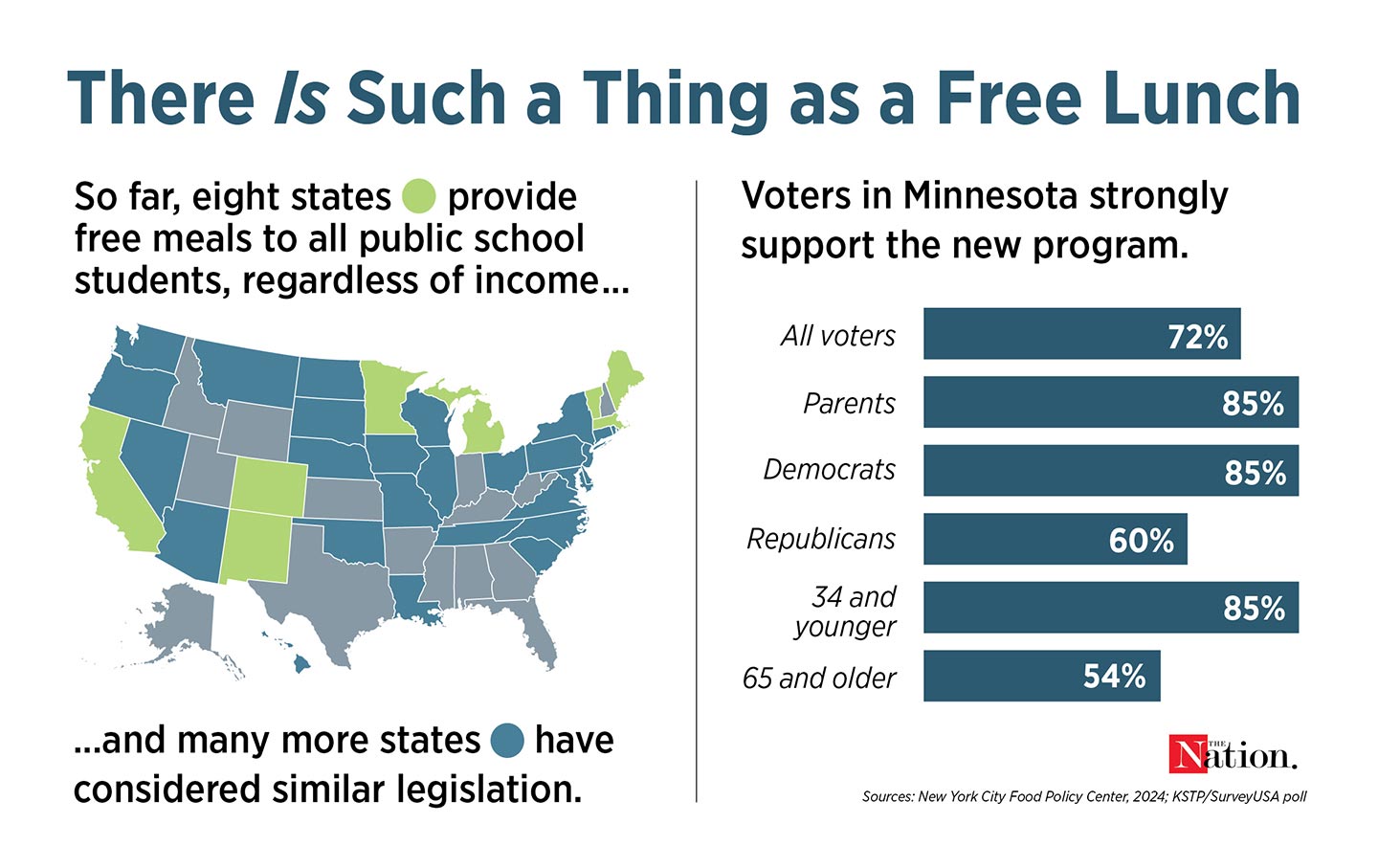

If you’re outside of Minnesota and had heard of Tim Walz before he was being considered as Kamala Harris’s running mate, it’s probably because you had seen a photo from March 2023 of more than a dozen children smothering the Minnesota governor with hugs, his face red with delight. That image was taken after Walz signed a bill making the state the fourth in the country to offer all students free meals at school.

Other politicians have also realized the merits of universal school meals. Danica Roem, who recently won a seat in the Virginia Senate, campaigned on the slogan “Fixing roads, feeding kids.” The policy has a multitude of benefits for families, schools, and the politicians who embrace it.

Access to school meals staves off children’s hunger and helps stabilize their families’ finances. When Congress instituted universal school meals during the pandemic, 95 percent of large school districts said it decreased student hunger. Before Covid, parents who lived in school districts with universal free school meals spent 5 percent less on groceries per month, and they reduced food insecurity among the affected households by nearly 5 percent. Despite the economic hardships of the early days of the pandemic, food insecurity for households with children fell in 2021, the last full year of the program, to a lower level than in 2019.

Full bellies lead to attentive minds. As Walz, a former teacher, noted, when “the kids are hungry, there’s going to be more problems.” And research backs him up. Students who get free school breakfasts have better attendance, behavior, and academic outcomes. A census study of Oregon found that free school meals lowered the likelihood of being suspended. This is what has happened in Minnesota, too, according to Walz: Attendance went up, and classroom behavior issues went down.

Parents want to feed their kids, but there are barriers to the current free and reduced-price school meals program. Before the pandemic, more than one in five food-insecure families didn’t qualify. The federal rules are strict: If a family makes a dollar over the income limits—for a family of four, $39,000 for free meals and $55,500 for reduced-price meals—they don’t qualify. Even if a family is eligible, it must make its way through a pile of forms.

The paperwork puts a burden on schools, too. During the pandemic, when there were no documents to process, school nutrition staff used the extra time to develop recipes and try new ingredients. Now that things have reverted to normal, half of the school nutrition programs that don’t have universal meals say that getting parents to submit the forms is a significant challenge. Worse, over 96 percent say unpaid meal debt has increased since the pandemic-era free meals ended, which means schools are now on the hook to track down the money or eat the cost. As of last fall, the median amount accrued per school without universal free meals was nearly $6,400.

The program also stigmatizes some students. Some schools have given children color-coded tickets to indicate who gets free or reduced-price lunches, and kids whose accounts accrue debt have been singled out in various ways, from being forced to eat cold jelly sandwiches to having their unpaid meals thrown in the trash. On the other hand, 57 percent of the schools that offer free meals to all report that stigma has decreased.

Universal school meals are also a gift to busy, stressed-out parents. Americans spend an average of 39 minutes a day preparing and cleaning up after meals. As with most domestic labor, this falls more heavily on women, who spend about twice as much time making meals as men. Those numbers don’t account for the fact that parents who work full-time typically need to get up early to pack lunches for their children (not to mention make breakfasts).

Walz understands this. The most feedback on his state’s universal meals program has been from families, “especially mothers, because of the unequal distribution of domestic labor,” he said on Ezra Klein’s podcast. “It was actually middle-class folks who were most jazzed about this,” he added.

This, Walz said, is part of why it’s such a popular program. Making it universal has helped all families of all incomes, giving them a reason to support its continuance. In a poll from earlier this year, more than 70 percent of Minnesota voters approved of it, more than any other policy polled. It’s so popular, in fact, that more children have used it than anticipated.