Less than two weeks before Election Day, Americans are drowning in opinion polls. New surveys are released at a rate of about a dozen per day. We are, by turns, heartened and tormented by the respected Quinnipiac, the troubling Times/Siena, the right-leaning Rasmussen. People who are not paid to attend to such matters can be heard using phrases like “sample size,” “margin of error” and even “cross tabs.” We are a nation obsessed.

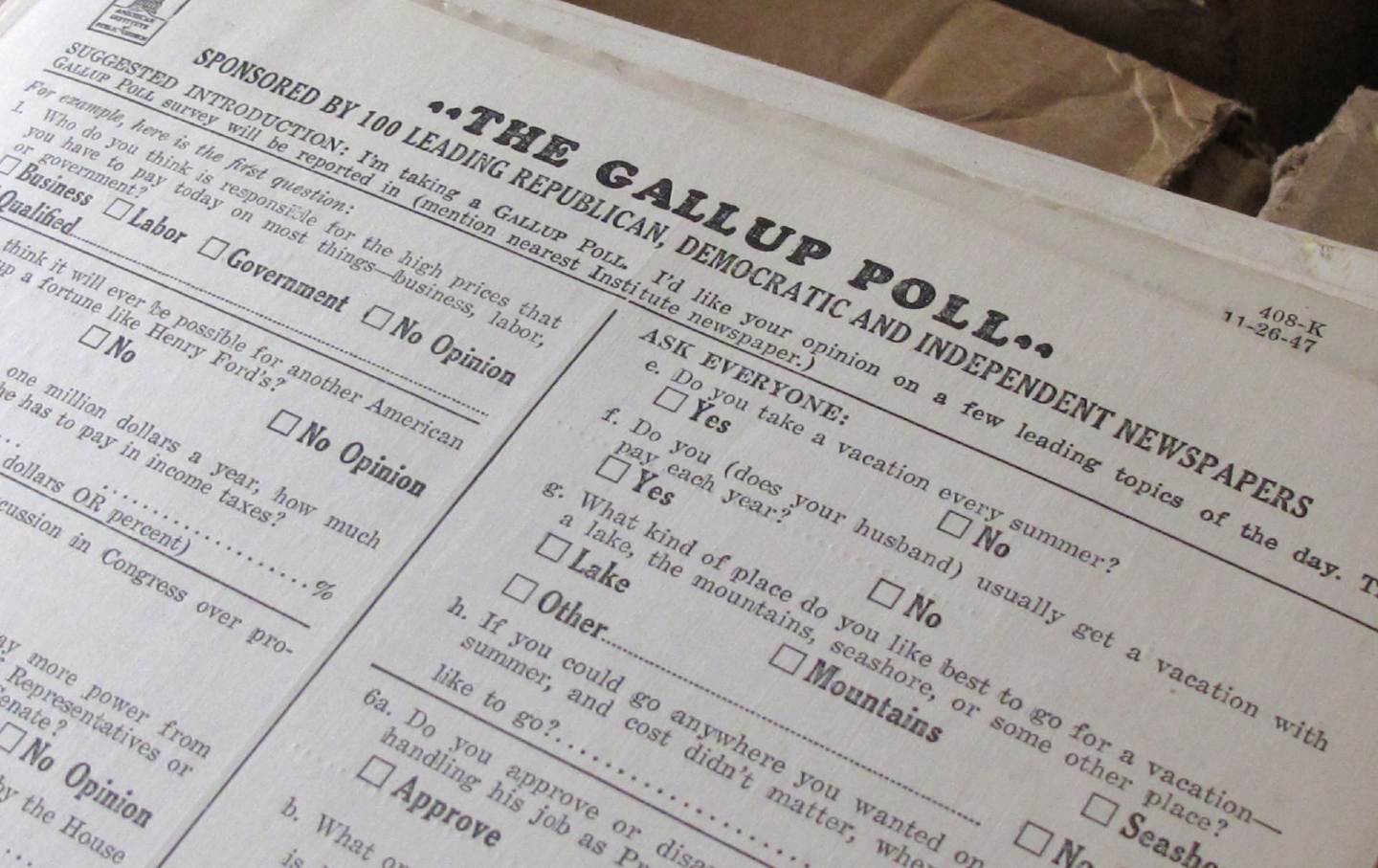

For this obsession we can thank, in part, George Gallup, who took public-opinion polling from the private-sector world of market research and applied it to American politics in the mid-1930s. He saw a problem with the informal and unscientific way polls were being conducted at the time. In 1936, Literary Digest went about surveying the public by scouring the phone book and car registration data and then sending millions of people a postcard asking whom they planned to vote for in the presidential election: Democratic incumbent Franklin D. Roosevelt or Republican challenger Alf Landon. Most respondents opted for Landon. The magazine predicted he would pick up 370 Electoral College votes. Landon wound up with eight. The magazine closed not long thereafter.

George Gallup, by contrast, knew that poorer voters who tended to support Roosevelt were less likely to have phones or cars. A former professor of journalism at Iowa State University, Gallup sought to craft a sample of voters that better reflected the voting public. By doing so, he predicted Roosevelt’s landslide in the 1936 election. On the strength of that success, he built a polling operation based in Princeton, New Jersey, which began publishing surveys of the American electorate’s opinions about both candidates and policies.

In early 1940, The Nation published an article about Gallup and the brand-new world of opinion polling, written by a 24-year-old James Wechsler, later the influential editor of the New York Post. Wechsler noted that, partly thanks to Gallup’s predictions in Roosevelt’s favor, most criticism of opinion polling was coming from conservative opponents of the New Deal, who argued that “polls are intrinsically a menace to the republic: they reveal only the sum total of popular ignorance; they foster the heresy that Mr. Milquetoast has something to say and a right to be heard even between election days; they thereby imperil the structure of ‘representative government.’”

While Wechsler didn’t share such antidemocratic concerns, he warned Nation readers to be skeptical of the profusion of opinion polls. After witnessing employees of Gallup’s American Institute of Public Opinion conduct interviews in three cities, he concluded that the potential for “manipulation of the polls by the conservative interests which ultimately pay for them” was a legitimate concern. (Gallup’s operation was funded by newspapers that subscribed to receive his data and reports.) “There is ample chance for sabotage along this assembly line,” Wechsler wrote.

Wechsler depicted Gallup as a nonpartisan expert “conscientiously groping for a vantage point above the battle where questions can be formulated in a spirit of peace and neutrality.”

Nearly five years later, Nation readers had a chance to hear from the man himself in a December 1944 article headlined, “I Don’t Take Sides.” He was responding to a critical essay the magazine had published two weeks earlier by a New Deal economist named Benjamin Ginzburg, who accused Gallup of refusing to share how he conducted his polling operations on the eve of that year’s presidential election. Whereas four years earlier conservatives had criticized Gallup, now it was Democrats who accused the pollster of putting out cooked survey figures.

In his Nation piece, Gallup dismissed the criticism as “unintelligent” and accused Ginzburg of “careless reporting,” while insisting that he welcomed any investigation of his polls. He also noted that, since both parties were accusing him of bias, he must be doing something right. “You can‘t make much of a case of political bias out of this record, unless perchance you regard us as chameleons who change political colors every two years,” Gallup wrote. “In this case at least one would have to admit that we distribute our political favors evenly.”

Gallup pledged that he and his institute had no political preferences and wanted only to predict the outcomes of elections correctly. He also insisted that, while he recognized there was “no social value in predicting elections,” his work contributed to the refinement of statistical methods that could perhaps be applied, more usefully, in other spheres of public life.

In his 1940 article, Wechsler depicted the polls as a useful addition to the democratic process. They gave voice to the common voter, who otherwise was rarely represented in the public discourse. “What have the answers to good questions, addressed intelligently to the right cross-section, proved about America?” Wechsler asked. “Above all they have revealed an incredibly animated populace anxious to articulate its fears, resentments, and loyalties.”

For Wechsler, it was the process, as much as the outcome, that gave polls their meaning. “[T]here is a perceptible undertone of excitement in these interviews which the statistics don’t record; to a host of Americans the polls represent a unique adventure in democratic life,” he noted. “On issues which have immediate personal impact, like involvement in war, they grasp at the chance to divulge what they are thinking, with the hope that someone in Washington will see the answers.”

“After watching fifty interviews,” Wechsler went on, “I could cite a large number of cases in which the answers were based on half-knowledge and intuition. But against those I could cite many others in which keen insight was revealed by people who were, in a sense, just learning to talk because nobody had previously asked them anything.”

“[T]he polls,” he concluded, “have encouraged the suspicion that Americans have minds.

It’s not obvious that opinion polls these days do much to encourage such suspicions, and one could hardly say that ordinary citizens are otherwise denied the chance to have their say in the public square. In a world overwhelmed by data, perhaps we might all do better to tune out the cacophony of polls and look to more qualitative sources of information in order to understand what truly animates the pulse of American democracy.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →We cannot back down

We now confront a second Trump presidency.

There’s not a moment to lose. We must harness our fears, our grief, and yes, our anger, to resist the dangerous policies Donald Trump will unleash on our country. We rededicate ourselves to our role as journalists and writers of principle and conscience.

Today, we also steel ourselves for the fight ahead. It will demand a fearless spirit, an informed mind, wise analysis, and humane resistance. We face the enactment of Project 2025, a far-right supreme court, political authoritarianism, increasing inequality and record homelessness, a looming climate crisis, and conflicts abroad. The Nation will expose and propose, nurture investigative reporting, and stand together as a community to keep hope and possibility alive. The Nation’s work will continue—as it has in good and not-so-good times—to develop alternative ideas and visions, to deepen our mission of truth-telling and deep reporting, and to further solidarity in a nation divided.

Armed with a remarkable 160 years of bold, independent journalism, our mandate today remains the same as when abolitionists first founded The Nation—to uphold the principles of democracy and freedom, serve as a beacon through the darkest days of resistance, and to envision and struggle for a brighter future.

The day is dark, the forces arrayed are tenacious, but as the late Nation editorial board member Toni Morrison wrote “No! This is precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.”

I urge you to stand with The Nation and donate today.

Onwards,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

How Loyalty Trumps Qualification in Trump Universe How Loyalty Trumps Qualification in Trump Universe

Meet “first buddy” Elon Musk.

Bury the #Resistance, Once and For All Bury the #Resistance, Once and For All

It had a bad run, and now it’s over. Let’s move on and find a new way to fight the right.

Trans People Shouldn’t Be Scapegoated for Democrats’ Failures Trans People Shouldn’t Be Scapegoated for Democrats’ Failures

Politicians and pundits are stoking a backlash to trans rights in the wake of the election. They’re playing a dangerous game.

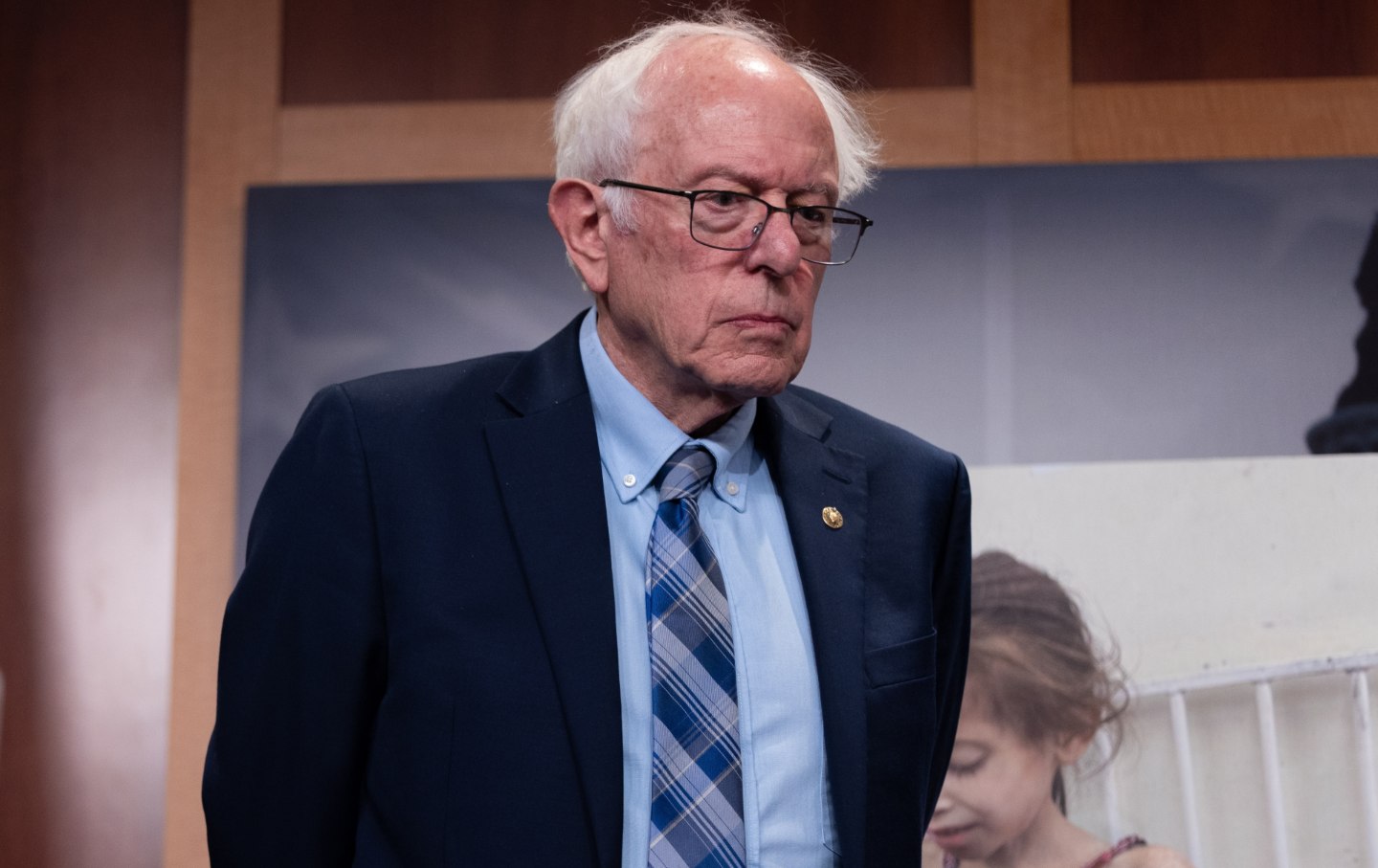

Bernie Sanders Is Leading a Bold New Effort to Block Arms Sales to Israel Bernie Sanders Is Leading a Bold New Effort to Block Arms Sales to Israel

The senator has more allies than ever in his fight to hold Israel accountable and save lives in Gaza.

Will “Serious” Republicans Block Any of Trump’s Freak-Show Cabinet Picks? Will “Serious” Republicans Block Any of Trump’s Freak-Show Cabinet Picks?

Will they stand up to even the scariest of these nominees? I’m not optimistic.

Harris’s Gaza Policy Was a Disaster on Every Level Harris’s Gaza Policy Was a Disaster on Every Level

Palestine may not have swung the election one way or another. But Democrats unquestionably paid a high price for their refusal to hold Israel accountable.