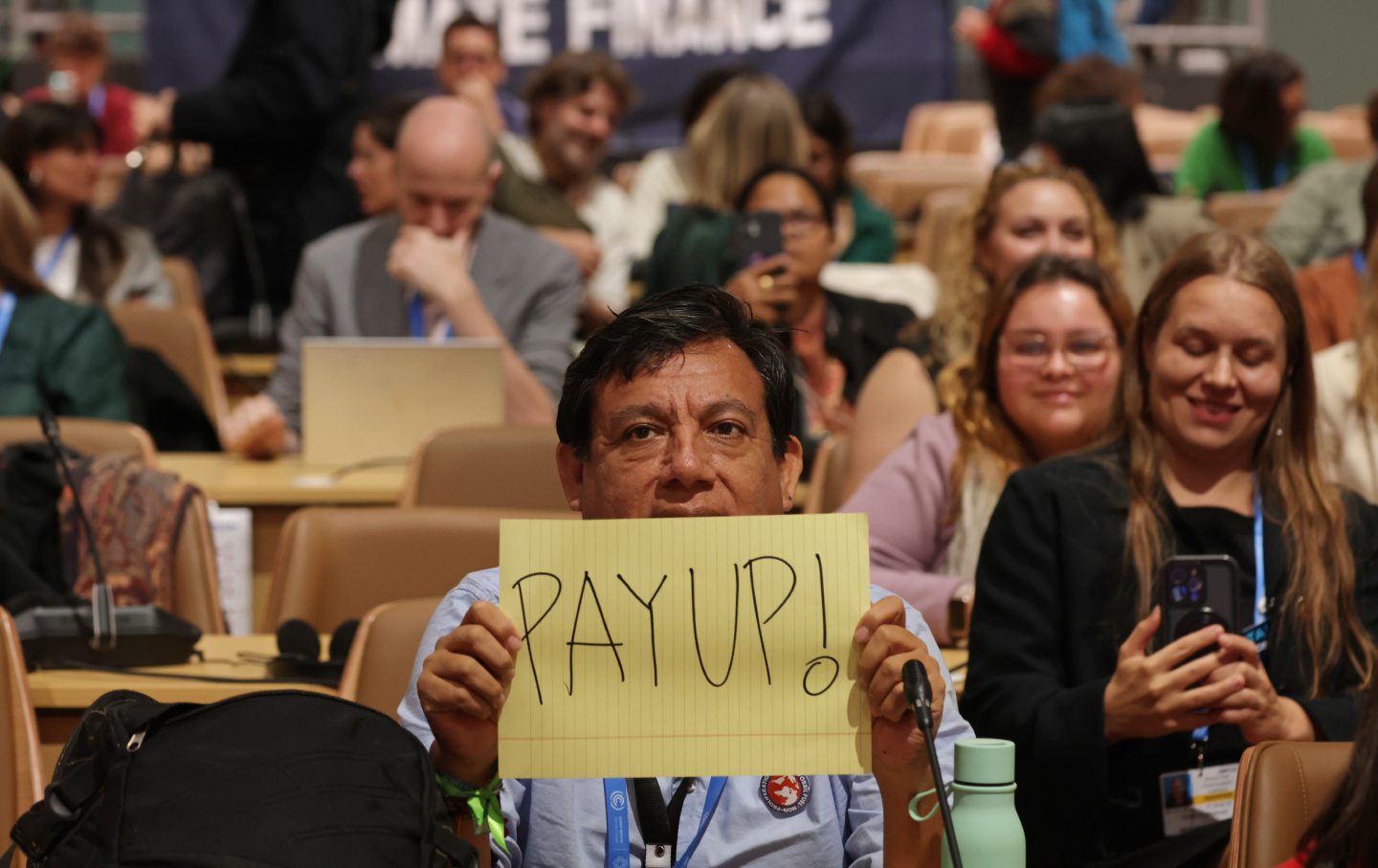

Activists, including one holding a piece of paper with “Pay Up!” written on it, in reference to demands for climate finance for developing countries, arrive to attend the “People’s Plenary” on day 10 at the UNFCCC COP29 Climate Conference on November 21, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan.

(Sean Gallup / Getty Images)

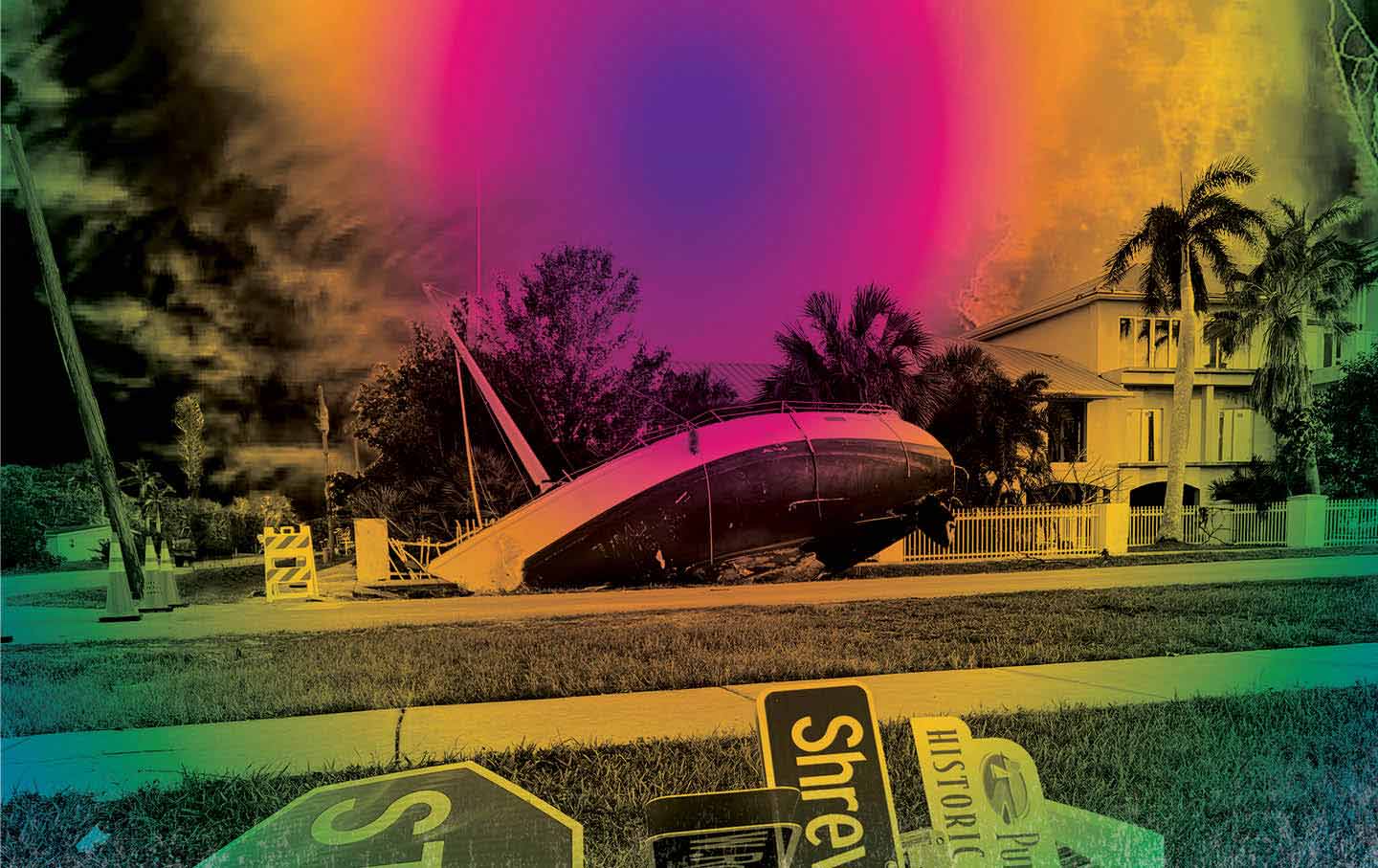

Baku, Azerbaijan—I first saw Lidy Nacpil holding court in one of the hallways of the labyrinthine Baku Olympic Stadium at COP29. Sitting in a circle on the floor, activists wearing T-shirts calling on big carbon emitters to “Pay Up!” hung on her every word.

Nacpil has been an activist in her native Philippines since the early 1980s when she joined student protests against Ferdinand Marcos’s dictatorship. There she met her first husband, fellow activist Lean Alejandro, who was murdered by hired gunmen when he was just 27 years old.

Since her early activism days, Nacpil has become a world-leading environmental-justice activist and is the coordinator of the Asian People’s Movement on Debt and Development, also known as Jubilee South. She has been a longtime advocate for debt-free climate justice to developing nations, ending fossil-fuel subsidies, and imposing a global wealth tax.

She has recently been coordinating the people’s plenary and the “Pay Up” demonstration movement here at COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan. Nacpil’s messaging was reflected at the highest level of COP when the UN Secretary-General Antonío Guterres delivered his remarks at the opening of COP this year, saying, “Pay up, or humanity will pay the price.” This slogan, along with the slogan demanding that climate justice financing should be paid in “trillions, not billions” has been echoed across COP29, appearing in the speeches of ministers across high-level meetings, at plenary sessions, and in demonstrations.

Nacpil, who is in a wheelchair, manages to be seemingly everywhere at once. This conversation itself is stitched together from several 10-minute interviews, when our first sit-down meeting was interrupted when her colleague asked if she wanted to participate in a demonstration halfway across the conference stadium. Without missing a beat, she was ready for action.

Running alongside her, her sense of commitment and urgency was obviously. “The action is happening now—we need to go now,” she said to the young man was pushing her wheelchair. I quickly gave up trying to keep up. For Nacpil, there is no time to waste.

—Carol Schaeffer

Carol Schaeffer: Can you tell me a about your history as an activist and how you came to climate justice in particular?

Lidy Nacpil: Like many activists, I started in my student days. My background as a biology student drew me to climate, as well as wanting to stop the many environmentally destructive projects of the Marcos dictatorship at the time. But I realized it brought many things together because climate is about more than saving trees, forests, wildlife, and so on. It’s about people. But it’s also about inequitable economic systems. It’s not by accident that the richest countries in the world are both wealthy and most responsible for the global greenhouse gas emissions. The economic system that has brought that about is the system that also has made them very rich.

And it’s an urgent problem. It’s not like we can afford to spend the rest of our lives, and then waiting on future generations to carry on. There has to be major results in our lifetime.

CS: Tell me about Pay Up. What are the demands, and what’s the current state of negotiations?

LN: Developed countries agreed in the 1992 Climate Convention to provide climate finance to developing nations, acknowledging their historical responsibility for climate change. The Global South, while bearing the brunt of loss and damage, demands funding not only for adaptation but also for mitigation to help decarbonize by 2050. This benefits global emission reduction efforts.

Historically, developed countries have emitted the most greenhouse gases, which remain in the atmosphere for thousands of years. It’s only logical that they not only have to reach net zero in their own countries, they also have to cover the cost of reaching zero elsewhere. But we will pay for a fair share based on our historical responsibility. So that’s why we use the slogan “Pay Up,” because they haven’t been paying up.

The long-standing pledge of $100 billion per year, made in 2009, is outdated and insufficient. Negotiations on a New Collective Quantified Goal emphasize the need for trillions of dollars, not billions. Public finance over private is essential because we need government-led regulation. We need programs that will blaze the trail. I have no doubt we will also need private financing, but private finance makes decisions based on profitability.

That’s why we use the slogan “Trillions, not billions.” We’re not going to accept any amount that is not expressed in terms of trillions.

CS: The current number that I’ve seen on the table is $1 trillion annually. Where did your number of $5 trillion annually come from?

LN: This is based on our estimates given several studies.

It is important to start with the data available. A lot of reported numbers are based off a needs-determination report, and we know that less than half of developing nations submitted what’s called their biennial report. So even based off half-reported needs, the estimate is already in the area of more than $2 trillion per year until 2030. And this is only about mitigation and adaptation, which does not include loss and damage. Loss and damage separately ranges from $400 to $800 billion, so that’s more than $3 trillion added together.

Then there’s also the cost of a fair and just transition to not leave workers without jobs, communities without livelihoods. And then building up the renewable energy systems to replace fossil fuels. So add it all up, and a nice round number of a minimum estimate is $5 trillion. These are low estimates. So we’re saying a down payment of $5 trillion is about what we need. Of course, we’re not expecting this process to come up with a $5 trillion this year.

I mean, we will be lucky to have some trillion number, but this is a fight. We intend to continue not just in this. So $5 trillion is a low benchmark that we need to put out there so that governments know what numbers we should be talking about.

CS: I just want to put a trillion dollars into perspective. The total federal budget of the United States is $6.75 trillion. The next biggest economy in the West is Germany, and their entire federal budget is half a trillion. So this demand for $5 trillion, where is it going to come from?

LN: First of all, there is a way to still put together some money from existing budgets to contribute towards the $5 trillion. We are challenging all the northern governments, for instance, to reduce their spending on military, to cut out all the subsidies for the fossil fuel industry. And that doesn’t mean it should all go to overseas climate finance. They should also look at prioritizing public services and climate action inside their own countries.

But there is a way of taxing the world’s wealthiest companies, high-worth individuals and families. That is one very clear way that this money can be raised. There are also other ways of raising these funds.

We point, for example, to Covid funding, and the way they collectively together raised about $16 trillion. And this is more terrifying than Covid. Covid in the short run, of course, killed so many people. But we’re talking about billions of people at risk in the next two decades if they don’t act now.

So we can’t see why they still keep insisting that it’s not possible.

CS: And what’s the role of multilateral banks like the World Bank and also private finance in financing this global climate justice?

LN: Our first call to them is stop financing fossil fuel projects. The very least they can do is do no harm. Now, if they want to support the climate transition, there has to be a huge change in their nature as banks, because we don’t want lending or loans for adaptation, for loss and damage. It defeats the entire purpose of climate finance if it’s coming in the form of these loans, especially for these areas of spending. There’s no money to be made. How are we going to pay back loans?

What we want is a system that’s not just based on your capacity to pay; it’s an energy system that is able to give access for those who can barely afford the energy costs right now.

There is a role for concessional lending for energy systems. And so we’re saying that they should locate the role in there. But for other climate actions, it should be grants.

Now, the other thing that we’re talking about is private finance. So private corporations, because many in the industries are private, they should pay for the cost of greening their industries, making sure they reduce their emissions. We can’t let public funds be subsidizing the cost of them greening their own industries. Public funds are meant to ensure that we have services, that those who cannot afford are able to get the energy that they need, the resilience building of communities, and so on. But for corporations, organizations, greening their industries, making sure they run on renewable energy, not fossil fuel energy, they should assume the cost of that. So there is indeed a very important role for private financing, and that is especially for decarbonization of private industries, and they should share that cost.

CS: Currently, 90 percent of existing climate financing is dedicated toward mitigation versus adaptation, which includes loss and damage. Do you want that percentage to change? Do you want a higher percentage of climate funding to go toward adaptation and loss and damage or more toward mitigation?

LN: There are two things we want. One is to increase the amount of climate finance streams. There has to be a balanced allocation for both mitigation and adaptation, as well as loss and damage.

Mitigation is about solutions, but an adaptation and loss and damage is about, in the meantime, what do our people do? Until that we have solved climate change, we are suffering the destruction, the losses. We need to adjust, we need to adapt, we need to build resilience.

So it’s very hard to say which one is more important. We keep insisting that there has to be a balanced allocation of what climate finance flows there are. But right now, urgently, we’re calling on an increase.

CS: And what will your response be if your demands are not met this week?

LN: We’ve known for a long while that we need to continue to fight.

If our demands are not met here, we will continue to fight, not just in the next COP but throughout the whole year, because this is not the only arena for fighting, for demanding the climate finance that we need. We need to confront the governments of the rich countries directly.

We have been mobilizing in front of their embassies, for instance, in between COPs. We have been sending out messages, doing media work. We will continue that fight because that climate justice money is so urgent.

In the meantime, while we’re doing that, we’re also, of course, campaigning for our governments to pay more attention to climate action, to do what we can with our own budget. It’s not like we’re just calling on the Global North. We’re also doing our work at the national level to make sure our government has their priorities straight on public spending.

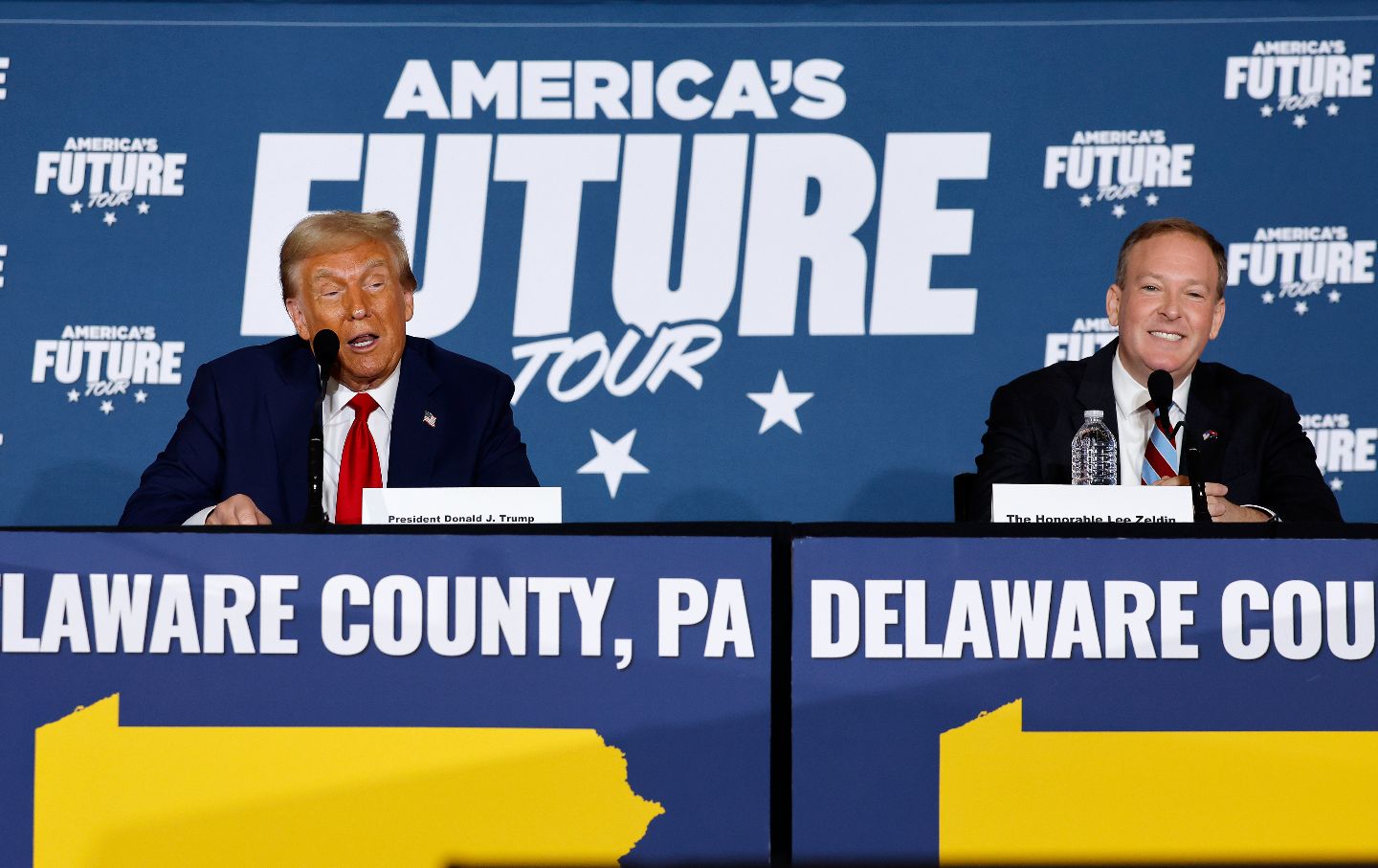

CS: You survived a dictatorship. Do you have any advice for activists or people that are worried about life under Trump?

LN: The first is not to lose hope because we’ve suffered through horrific experiences under a dictatorship, under Marcos, for instance.

And if we work together and struggle together and persist, it will not take a short time. We know that. Then we will experience victories, too. It never finishes the work of striving for justice.

But it’s not like you’re just simply marching in place. You do progress. You do advance. And if you’re lucky like me, in your lifetime, you can see many dramatic changes, which are the fruits of your work together with many other groups. We need to keep the faith. We shouldn’t lose hope. We shouldn’t get depressed. We should get angry and channel that anger into productive work. That would be my message.

We cannot back down

We now confront a second Trump presidency.

There’s not a moment to lose. We must harness our fears, our grief, and yes, our anger, to resist the dangerous policies Donald Trump will unleash on our country. We rededicate ourselves to our role as journalists and writers of principle and conscience.

Today, we also steel ourselves for the fight ahead. It will demand a fearless spirit, an informed mind, wise analysis, and humane resistance. We face the enactment of Project 2025, a far-right supreme court, political authoritarianism, increasing inequality and record homelessness, a looming climate crisis, and conflicts abroad. The Nation will expose and propose, nurture investigative reporting, and stand together as a community to keep hope and possibility alive. The Nation’s work will continue—as it has in good and not-so-good times—to develop alternative ideas and visions, to deepen our mission of truth-telling and deep reporting, and to further solidarity in a nation divided.

Armed with a remarkable 160 years of bold, independent journalism, our mandate today remains the same as when abolitionists first founded The Nation—to uphold the principles of democracy and freedom, serve as a beacon through the darkest days of resistance, and to envision and struggle for a brighter future.

The day is dark, the forces arrayed are tenacious, but as the late Nation editorial board member Toni Morrison wrote “No! This is precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.”

I urge you to stand with The Nation and donate today.

Onwards,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation