Soap Opera Thriller

Alfonso Cuarón’s Disclaimer.

The Empty Thrills of Alfonso Cuarón’s “Disclaimer”

Why did the great Mexican filmmaker make a soapy thriller?

A scene from Disclaimer.

(Courtesy of Apple TV+)

Disclaimer, Alfonso Cuarón’s new series on Apple TV+, is about narrative and its relationship to truth. The series is, at its core, a simple melodrama, but its layers of excessive voiceover tend to reduce narrative to literal narration. Disclaimer wants to tell a complicated story, but it does so by spelling out exactly what its characters are thinking and feeling. Insisting on the ambiguities of its narrative, it is an exercise in storytelling that also wants to make sure we do not miss its lesson.

The miniseries is the first work Cuarón has directed since his film Roma, which garnered three Academy Awards in 2019, including Best Directing and Best Foreign Language Film. Set in the early 1970s, Roma drew from the writer-director’s upbringing in Mexico City and followed the experiences of a Mixtec housekeeper caught up in a time of personal and political turmoil. Roma was an unavoidably personal picture, but Disclaimer, with its multiple storytellers, gesturing orchestral score, and visually demarcated timelines, feels impersonal and overwrought.

Cuarón adapted Disclaimer from a novel of the same name by Renée Knight, a beach-read mystery in which dueling perspectives build up to a revelation. The series is a prestige soap, no getting around it, filled with sex and scandal and a mysterious death. But rather than drawing us into the events of the story, or even giving us the simple pleasures of its genre, it ends up being oddly didactic, so concerned with making its point that it flattens the subtlety and suspense that can be delivered by good craft.

Disclaimer begins with our introduction to Catherine Ravenscroft (Cate Blanchett), an accomplished documentarian whom we first see getting a big award for her work. Catherine is a truth teller who reveals the devious secrets of the powers that be. But she also has her own secret, as becomes clear when she receives a book in the mail that threatens to expose it: a self-published roman à clef that purports to reveal how her actions led to the death of a teenager 20 years earlier. Catherine immediately recognizes herself in the novel, and the guilt, lies, and concealment all bubble up to disrupt the seemingly calm surface of her life.

Catherine’s own shock of recognition spreads to those closest to her: her husband, Robert (Sacha Baron Cohen), who runs a foundation that launders his family’s generational wealth, and her adult son, Nicholas (Kodi Smit-McPhee), who can barely hold down a job and is thrust out to live on his own for the first time. They, too, get copies of the book, along with lurid photographs of the young Catherine that appear to confirm its depiction of her. Then the book spreads among her coworkers as well. Never mind that reasonable people might question the veracity of a self-published book that has appeared out of thin air or wonder why they are receiving it—everyone seems eager to cancel Catherine.

The catalyst for all this conflict is Stephen Brigstocke (Kevin Kline), a musty old widower who has drifted through life with no purpose until he finds a manuscript and some old photographs left behind by his late wife, Nancy (Lesley Manville). In those pages, Stephen reads about his son, Jonathan, a helpless young teenage boy enthralled by an older woman (apparently Catherine), whose cruelty leads to his death. Stephen is now determined to right this wrong—or at least to exact his revenge.

Stephen devises a plan that will strip Catherine of all the success, reputation, and familial affection she has gained over the past 20 years. He sees himself as an avenger of injustice, and his life is renewed by this pursuit; he is giddy with excitement. When he leaves a copy of the book for Catherine’s son, he mimes tossing a hand grenade. Stephen might as well be twirling his villain’s mustache, though at least he’s having fun—even if no one else is.

As a director, Cuarón always adjusts his formal techniques to match the demands of each individual film. In his science-fiction thrillers Children of Men and Gravity, he takes viewers into different worlds with long, immersive tracking shots. In Roma, his black-and-white photography stays parallel to the action and establishes a flatter, more objective perspective in the midst of familial drama.

In Disclaimer, Cuarón again leverages light and color, shot length and movement, to narrate his tale of secrecy and competing truths. Working with two cinematographers—Emmanuel Lubezki, his longtime collaborator, and Bruno Delbonnel—he welds their distinct styles to distinguish between the events of the present and the recent past and those of 20 years earlier.

If nothing else, the series is so gorgeously photographed that it makes you want to watch it on mute. Look at how Lubezki films the encroaching dawn in the Ravenscroft kitchen, how the sun peeks in through the curtains when Catherine wakes into her nightmare. When her husband is struck by Stephen’s ammo, the photography switches to an unsteady handheld look, full of shakiness and dramatic zooms. The scenes in Italy, photographed by Delbonnel, are romantic and soft, almost ethereal, pink and orange like the sunset. Yet when combined with everything else, these contrasting visual styles come to feel overly literal. Want to guess which scenes are meant to depict a version of events that may prove to be only loosely tied to reality?

Disclaimer distrusts not only its audience but its own images. The series is bathed in various voice-overs that sometimes deliver exposition in the most direct way possible but also often narrate the very events we are watching. We learn about the memory issues that Catherine’s mother is dealing with just before a phone conversation illustrates these same issues; we learn about Robert’s disappointment with Nicholas just as we see him looking over his son’s sketchy apartment, his dismay etched on his face. We are told precisely what the core characters are thinking and feeling, leaving nothing to the imagination. It’s not just that the acting and visual storytelling are made to feel redundant, but that the audience is robbed of one of the key attractions of a serialized and soapy mystery: the pleasure of connecting the dots.

There’s probably a point to all of this narrating. Cuarón wants to remind us that so much of our thinking and behavior at any given moment reflects our limited perspective, and that narratives, once they take hold, can shape and affect our perception of the truth. But rather than shading the story with doubt, this tactic erases ambiguity.

It eventually becomes clear that there is a twist or revelation coming. Yet the series stacks the deck so much in one direction that, when it does come, the twist feels almost formulaic: the unvarnished truth that overturns and condemns all the other supposed truths the show has fed its viewers. What does it mean, though, that Disclaimer has spent a good 90 percent of its run time airing and developing a set of assumptions that are now entirely discarded? Cuarón has stated his desire to confront viewers for their own judgment of Catherine, to reveal the ambiguities found in all narratives—and yet it’s a judgment that the show itself imposes on them. As Phillip Maciak observed in The New Republic, to achieve his gotcha moment, Cuarón ends up doing to the audience exactly what his show claims to condemn: It “commits the sin in order to eventually point a finger at us viewers for committing it, too.” Disclaimer goes for shock and indignation rather than empathy.

Perhaps the moral of the story would land better if the world that Disclaimer imposes on us were at least fun to inhabit. The same material could have been presented as a thriller, such as Gone Girl, or a dark comedy soap like Big Little Lies. Then you could at least draw viewers into investing in the story, only to rupture their assumptions later. Yet even as genre fare, Disclaimer has no winking self-awareness, no hint of camp, and takes no pleasure in its tropes—in short, it’s no fun. But you can’t condemn us for investing in a false narrative if you never got us to buy into it in the first place.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

The Best Albums of 2025 The Best Albums of 2025

From Mavis Staples to the Kronos Quartet—these are our music critic’s favorite works from this year.

Forrest Gander’s Desert Phenomenology Forrest Gander’s Desert Phenomenology

His poems bridge the gap between nature’s wild expanse and the private space of one’s imagination.

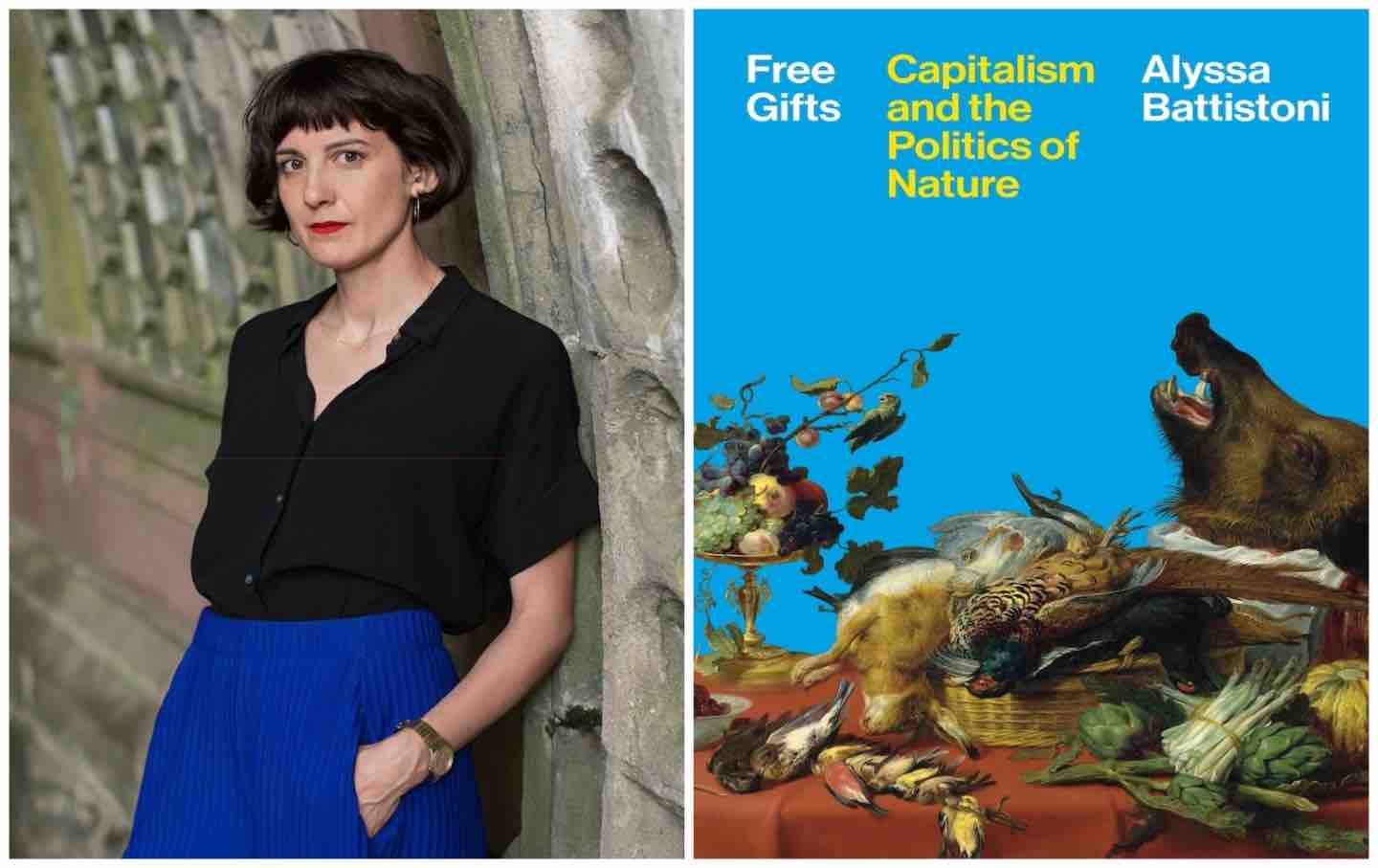

Capitalism’s Toxic Nature Capitalism’s Toxic Nature

A conversation with Alyssa Battistoni about the essential and contradictory nature of capitalism to the environment and her new book Free Gifts: Capitalism and the Politics of Nat...

Solvej Balle and the Tyranny of Time Solvej Balle and the Tyranny of Time

The Danish novelist’s septology, On the Calculation of Volume, asks what fiction can explore when you remove one of its key characteristics—the idea of time itself.

Muriel Spark’s Magnetic Pull Muriel Spark’s Magnetic Pull

What made the Scottish novelist’s antic novels so appealing?

Luigi Pirandello’s Broken Men Luigi Pirandello’s Broken Men

The Nobel Prize-winning writer was once seen as Italy’s great man of letters. Why was he forgotten?