When the Feds Are Still Watching

Former Black Panthers fear the FBI is still keeping tabs on them decades after COINTELPRO. In at least one case, they were right.

Malik Rahim.

(Bryan Tarnowski)On a warm afternoon in 1970, Cleo Silvers, then a young member of the Black Panther Party, boarded the subway from the Bronx to Harlem. COINTELPRO was at its height. Fred Hampton had recently been assassinated by police in Chicago. Huey Newton was imprisoned on false charges. She was still on the subway when police stopped her.

“I told them, ‘I’m going to the Black Panther office, and you better leave me alone,’” recalled Silvers, now 78. And they did. By the time she got to the Panther headquarters on Seventh Avenue, she breathed a sigh of relief, and continued with her work: within a few months, she’d be helping to take over a hospital.

Silvers recounted this day recently, sitting at her kitchen table, bedecked in a mauve headwrap and gold jewelry. Anyone looking in the window would see just another Tennessee academic, the rooms she shares with her husband, Ron, overflowing with books on racial justice and radical organizing. But Silvers’s life has been one of boldness: as a Young Lord in the South Bronx in 1970, she took part in the Lincoln Hospital Takeover, when activists demanded better care for patients, supported by Assata Shakur and other Panthers. After the takeover, Silvers helped run a door-to-door program with the Young Lords, testing people for tuberculosis and lead.

Throughout this time, Silvers, like so many of her radical peers, was on the radar of the FBI. The bureau’s notorious COINTELPRO program—a campaign of covert and illegal operations aimed primarily at subverting civil rights and anti-war movements—was in full swing. Government operatives spied on, intimidated, smeared, harassed, blackmailed, wrongfully imprisoned, and assassinated dozens of Black leaders and radicals like Silvers until it was officially shuttered in 1971. Silvers’s name appears repeatedly in the 110,000-page cache of declassified FBI files on the Black Panthers, according to Bob Boyle, the attorney who obtained them. Decades later, congressional hearings and public apologies have served to frame COINTELPRO as a dark American chapter, one relegated to the dustbin of history.

It’s 40 years since Silvers was last arrested and questioned about the Black Panther Party. About 45 years since the FBI visited her family to interrogate them about her whereabouts. More than 50 since she was betrayed by her own boyfriend, who she found out decades later was an FBI informant. And though the FBI’s pursuit of the Black Panthers officially ended, the government’s targeting and surveillance of radical activists never did.

Silvers believes that she endured FBI harassment for decades following the official end of COINTELPRO. She told The Nation that FBI agents contacted her bosses and got her fired from multiple jobs, sometimes leveraging the federal grants that nonprofits needed to operate. When she was working for a workforce training program in 1995, she said, she was told by a friend that “the FBI came in and told [Silvers’s supervisor] that you were a Black Panther, and that it would be better for her to fire you than to lose the entire program.” Silvers was let go. (The person Silvers named as her former supervisor strongly denied to The Nation that this had occurred.)

In 2002, Silvers said, she was working for Long Island University when her boss told her, “You are doing a wonderful job. But I have to ask you—what in the world did you do to the government? What did you do to the FBI? They are so angry at you.” Her boss went on, “They have come here and told me that I have to fire you.” She was let go again.

As the NYPD discovered in 1971, Silvers doesn’t scare easily. But years of harassment left their mark. And today, daily, she feels the feds on her heels.

“They continue to actively target us,” Silvers said. She believes her phones are still tapped and her apartment bugged. She sees people follow her into grocery stores, buy nothing, and follow her out. She is approached and befriended by strangers who then mysteriously disappear without a trace, sometimes after suggesting they jointly pursue some criminal venture (e.g., life insurance fraud).

Wary, Silvers takes precautions. Sometimes she pours oil all over her trash, to spoil private documents and keep agents off the trail. Twice, she said, she’s seen Tennessee Bureau of Investigation (TBI) plates on SUVs that were following her: “I think they do it to let me know that they’re there.”

To some, this might smack of paranoia. And at times, Silvers’s husband, Ron, is gently skeptical. When Silvers suggested that a neighbor had left a recorder in their couch, Ron disagreed, finding the speculation a step too far.

But “the thing is, you really can’t tell,” he said. “From time to time, I have had the impression we’re being followed.”

The Nation requested relevant public records in an attempt to prove, or disprove, Silvers’s suspicions. The TBI replied that “all TBI investigative records, both closed and open, are considered confidential.” A FOIA request regarding Silvers filed 17 months ago is still awaiting a response. Typically, any documents that come back are heavily redacted.

In fact, it’s the uncertainty itself that contributes to the surveillance PTSD experienced today by aging Black activists like Silvers. Surveillance PTSD, also common among young men who’ve experienced multiple police stops, manifests as hypervigilance, anxiety, depression, and mistrust of formal institutions, including health clinics and banks. Sometimes it’s the very inability to know whether you’re really being watched, or you’re simply being paranoid, that is most unsettling of all.

Frederika Newton, widow of BPP cofounder Huey Newton, still operates constantly under the assumption that she’s being surveilled. She knows that, as a result, some people might think the way she works is unusual.

“Living with it so long, it’s hard to say how it’s affected me. It’s gotten so normalized,” she said, speaking by phone from Oakland, where she is president of the Dr. Huey P Newton Foundation, which aims to preserve Huey Newton’s legacy and correct decades of FBI-propagated disinformation about the Panthers. Today, she said, her younger colleagues, who never experienced the abject violence of 1960s COINTELPRO, “think I’m paranoid—that’s the only time I notice. My reality isn’t other people’s reality.”

But of course, sometimes, you do get to know what’s true.

On a warm winter afternoon, Malik Rahim hunched in his darkened living room in New Orleans, the walls plastered with decades of Black radical flyers and photographs, paging through a thin sheath of public records. Rahim, also a former Black Panther, is a renowned community organizer in New Orleans; he can’t walk a block without a car slowing to wave at him, one driver after another lifting fists of solidarity. He’s perhaps most known locally for founding the nonprofit Common Ground in the wake of Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Common Ground and its health clinic served a half a million Katrina survivors in its first year. In 2019, Rahim received a Living Legend award from the Southern University of New Orleans honoring his work. In a box near his couch sits a framed Lifetime President’s Volunteer Service Award, recently received from President Biden.

For years, Rahim had suspected—but never been able to prove—that the FBI had targeted him. Now, government documents showed that he was correct.

Documents obtained last year by The Nation show that in August 2006, a year after Katrina, the New Orleans Joint Terrorism Task Force (JTTF), a federal-police amalgamation led by the FBI, began conducting a “threat assessment” of Malik Rahim and Common Ground for “possible nefarious Domestic Terrorism or Anarchist activities.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The JTTF’s report claimed that Common Ground was distributing “propaganda” and “anti-government posters.” Under a section titled “Intelligence Gaps,” the JTTF posed several questions, like: “Is Common Ground planning any terrorist attacks against Louisiana government facilities?,” and, “What anarchist groups and gangs, besides the New Black Panther party, is the Common Ground Collective recruiting from?” It ends with a request for the JTTF to conduct an investigation into Common Ground.

Rahim was unaware of the FBI’s efforts until The Nation shared the files with him this year.

“The FBI really put secret agents on us,” Rahim said, shaking his head. “I knew that they was planning on either killing me, or doing a character assassination, [but] this is really fucked up.”

Here’s what Common Ground had actually achieved by August 2006: It had established a health clinic that served 15,000 residents; set up nine distribution centers; cleaned and gutted 1000+ homes and 12 churches; and served hundreds through the Common Ground Legal Team that monitored police harassment and abuse. They also distributed breakfast and had a kids’ bike shop and basketball tournaments.

The revelation is all the more disturbing because Rahim had tried, with Common Ground, to be explicitly nonpolitical. “We didn’t get involved in no election, because our goal was just offering relief,” he said.

Rahim noted that, contrary to the file’s claims, Common Ground had zero connections to the New Black Panther Party, which was founded in 1989 and is not related to the original BPP.

Even before these latest revelations, Rahim had, for almost two decades, lived under the same kind of uncertainty as Silvers. In 2008, it was revealed that his former friend the Common Ground cofounder Brandon Darby had at some point turned on the organization and become a notorious FBI informant, likely in late 2007.

Rahim’s voice was wounded as he explained how Darby’s betrayal affected him. It damaged Rahim’s relationship with his own son, who suspected Darby before his realignment became public. “I went against my own child” to defend Darby at the time, Rahim said.

It appears that the FBI may have undermined Common Ground’s efforts even before Darby flipped. Rahim and Common Ground spent much of 2005 and 2006 repairing a low-income housing complex called The Woodlands, in order to prevent hundreds of residents from being evicted. The owner, Anthony Reginelli Jr., agreed for Rahim to purchase the complex for $5 million.

But within weeks of the JTTF opening its investigation, Reginelli backed out of the deal and sold it to a property development group instead. The following month—just before Thanksgiving—all Woodlands residents received eviction notices. By January, hundreds were on the street.

And the FBI wasn’t done with Rahim. In March 2007, it opened a mail fraud case against him under the heading “terrorism enterprise investigation.” The case remained open for more than a year, according to the declassified documents, with occasional updates that speculate about putting Rahim in front of a grand jury. The FBI finally closed the case in August 2008, noting that “no evidence has been collected.” At the time, Rahim had just launched a campaign for a seat in the Louisiana House of Representatives as a Green Party candidate.

Reginelli and his ex-wife, then co-owner of The Woodlands, told The Nation they did not recall speaking with the FBI. The other two then-owners of The Woodlands could not be reached for comment.

As with Silvers, the surveillance of Rahim—and his uncertainty around it—has done lasting damage. Rahim sees threats all around him. He believes that white vigilantes poisoned his dogs last year—not so outlandish, considering that white vigilantes were shooting and killing unarmed Black New Orleanians in the wake of Katrina. On the day he went to accept his Living Legend award, his car was mysteriously towed. He says that officers from the nearby FBI fusion center jog past him on the levee and acknowledge him by name, just to let him know they know who he is. For decades, he’s been unable to get a passport or a driver’s license.

And yet even with the sheath of records in hand, it’s difficult to ever know exactly what is deliberate targeting by police forces, what is the product of systemic racism, and what is simply the difficulty of navigating the daily indignities of US bureaucracy, magnified by the anxiety of a lifetime’s state targeting.

Regardless, Rahim’s files lend credence to Silvers’s suspicions. Many aging Black Panthers remain active in justice organizing, and confer regularly on their efforts; Rahim visited Silvers’s apartment in New York City after Katrina as he sought to drum up support.

And yet this reality hasn’t immobilized Rahim. In October, he received funding to establish a community center in Algiers, near his home. It will be the first time since the investigation of Common Ground that he will have a space dedicated to his organizing work.

Rahim and Silvers are not outliers. The destabilization, the inability to know what’s real, to be haunted by uncertainty for decades—that’s the point. FBI briefs from 1971 describe their purpose as the inducement of “paranoia.” So COINTELPRO’s effects linger on, whether or not the program’s targets are still being actively surveilled by the state today.

Frederika Newton says her past experiences manifest today as mistrust of strangers and hypervigilance. She “walks the straight and narrow,” and keeps meticulous records. “Most people don’t have their attorney in board meetings,” she pointed out. And, like Rahim in 2006, she is wary of becoming a target by being too noticeable. “Other people get elated when we raise money. I get nervous,” she said.

Silvers is largely retired from organizing work, and often refers to her targeting with humor, rather than anxiety. But that doesn’t mean she feels safe. She still keeps an eye out for suspicious cars following her on her way to the grocery store, the nail salon, and the rehab center where she does physical therapy for her heart. She said her cardiac problems have been worsened by surveillance stress: “It’s still killing you, psychologically and physically, as you get older.” (The FBI has acknowledged the link between surveillance and debilitating stress in the past; according to a 1964 memo, the bureau took pride in hounding an elderly Puerto Rican activist so much he suffered a heart attack.)

“It’s like microaggressions,” said Silver—painful in part because they are both ubiquitous and hard to prove. When Silvers and her husband, an interracial couple, found that their tire had been slashed in a Memphis parking lot, they could attribute it to coordinated state efforts to intimidate them—or to regular Klan members, all of it part and parcel of the legacy of racial terror in the US South.

After all, when poison is in the atmosphere like that, it hurts everywhere. Whom can you trust? How can you know? How can it not drive you mad?

“Some of them [activists] lost their minds because of that,” said Silvers. “Some of them are unable to function today. Some of them are hiding. They don’t want to be connected with anything that has to do with the movement. Many of them say, ‘I love you, Cleo, but don’t call me anymore.’” She sighed. “Because they’re afraid. Afraid. More than nervous—afraid.”

More from The Nation

The People vs. ICE The People vs. ICE

Across the country, neighbors are working together to protect one another from Trump’s immigration crackdowns.

Puerto Rico’s Mothers Against War Turn to Revolutionary Love Puerto Rico’s Mothers Against War Turn to Revolutionary Love

Formed to oppose the Iraq War, Madres Contra La Guerra have now spent decades trying to end Puerto Rico’s role at the center of the US war machine in Latin America.

A Minneapolis Teacher Wants the Whole Country in the Streets A Minneapolis Teacher Wants the Whole Country in the Streets

Dan Troccoli, a public middle school teacher, says everyone should start “emulating” Minneapolis’s resistance to ICE and the Trump regime.

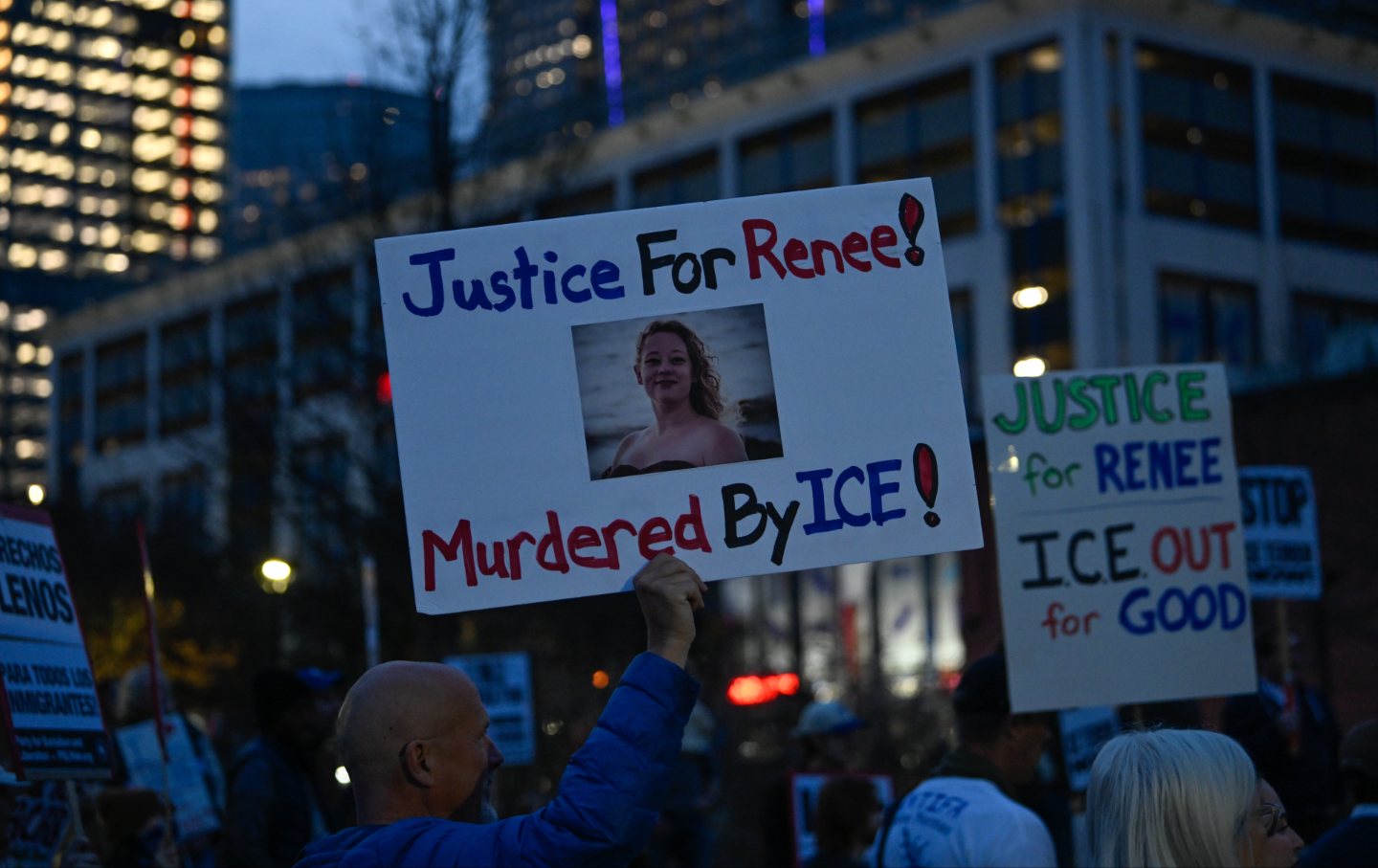

Let’s Make Renee Good the Last Person That ICE Kills Let’s Make Renee Good the Last Person That ICE Kills

We can turn the tide against Trump—but only with mass action and courageous leadership.

Liberals Think Antifa Isn’t Real. But It Is—and It Knows How to Win. Liberals Think Antifa Isn’t Real. But It Is—and It Knows How to Win.

To protect us all from the violence of the Trump administration, we must defend antifa.

Want to Stop ICE? Go After Its Corporate Collaborators. Want to Stop ICE? Go After Its Corporate Collaborators.

ICE can’t function without help from the private sector. So we should force the private sector to stop helping.