Medical Technology Makes Doctors Less Skillful. Should You Care?

Technological advances are transforming medicine, but it may be making your physician less creative.

Are technological advances making doctors lose the art of medicine?

(whitebalance.oatt / Getty Images)

Of the many patients waiting to be seen on that frigid November night in Ann Arbor, only one was silent. He offered nothing more than an uneasy gaze amid the clamor of the ICU’s step-down unit. He had been found unresponsive on the street before being brought into the emergency department where he was unceremoniously thrust back into consciousness. Though his vitals had stabilized, he could not leave: Hospitals cannot discharge an unidentified individual, and being nonverbal, he could not identify himself. When it became clear that the patient was not regaining his ability to speak, he was admitted to the hospital as a John Doe and wheeled off to the wards.

It was two hours into Alexandre Carvalho’s shift when he became acquainted with the case of the nonverbal John Doe. Carvalho, an infectious disease physician who was an internal medicine resident at the time, was used to seeing both nonverbal patients and John Does, but something about this man stood out. According to the admission notes, after being stabilized, the patient’s condition seemed consistent: He was not healthy, per se, but he did not appear to be deteriorating. He was caught in a sort of medical limbo: alert and oriented yet locked in his body, unable to speak or communicate. A CT and chest X-ray were ordered, and the scans revealed something shocking: a large hole in his lung.

The care team sprang into action, putting the patient into immediate isolation for fear of potential infectious causes. Was it tuberculosis? Cavitary pneumonia? Actinomycosis? The list of diagnoses quickly grew as the care team clustered around the computer screen. And then, just like that, police notified the care team that the John Doe had been identified and his family were here in the hospital. The attending physicians waved the police away, more focused on the technological findings than any explanations the family might provide. Carvalho watched this unfold in confusion. As no one else appeared interested, Carvalho slipped off to investigate what the family had to say.

After sitting with the family and talking to them about the patient, Carvalho mentioned the lesion that had been discovered on the CT. Apparently, it was not new. Years ago, the patient had attempted suicide by shooting himself in the chest. He survived, but had suffered a stroke as a complication and became nonverbal as a result. The hole in his lung was evidence of the bullet’s trajectory as it tracked through his chest cavity before exiting out the other side. “This workup [that] was thousands of dollars was not even the cause of the patient’s hospitalization,” Carvalho told me. It was nothing more than an incidental finding. Carvalho laughed as he shared that the “eureka moment of the diagnosis” could be boiled down to discovering the patient’s history by simply asking the family about it: “I think I gained this ability to get out of the technology a little bit by getting some of my training abroad.”

There are obvious benefits to medical technology. It can help detect diabetes, diagnose cancer, make highly accurate predictions in radiology, identify the presence of tuberculosis, and so much more. It can reduce human error. Some research even suggests that AI-powered applications in healthcare could improve patient outcomes by 30–40 percent while reducing treatment costs by up to 50 percent. But an increased use of medical technology has accelerated the problem of de-skilling, a reduction in the level of skill required to complete a task because some or all components of the task have been automated.

Historically, the term “de-skilling” has been used in the context of automation in manufacturing: While workers on assembly lines in the past were responsible for tasks that required manual skills such as constructing small parts or performing repairs, the advent of machinery reduced the need for workers to develop or maintain such a variety of high-level skills. Within the context of medicine, de-skilling refers to the decrease in a physician’s ability to derive information on the basis of detectable signs and symptoms alone, i.e., without technological aids.

Proper patient care requires a balance: an understanding of how to use medical technology as well as respect for the old-school method of learning each aspect of medicine for yourself, on the job. Coming to a diagnosis is a game of probabilities: There might be multiple possibilities that explain specific symptoms, but a doctor has to sift through them all and decide based on the patient’s history and their physical exam findings which ones are the most likely. Medical technology cannot fully supplant a physician’s intuition, and trying to use it as a replacement for this could result in a wasteful, excessive, and expensive process in which more tests are done than necessary. The problem is that every hospital—and every doctor—has a different idea of what the balance between technology and intuition should be. And as AI makes its way into the mix, it could further exacerbate the problem of de-skilling by offering more sophisticated shortcuts. Hospitals in the United States tend to lean much more on technology than in other countries, since US doctors have access to it and funding structures incentivize their use, but is it possible that US practitioners should be taking notes from doctors in more under-resourced areas who’ve had to make do with less?

Galant Chan, the program director of the internal medicine residency program at the Baylor College of Medicine, had many thoughts on how technology is integrated into medical education among the current class of up and coming US doctors. “Many things are different now,” Chan told me. “First of all, even before showing up at the bedside, our residents can glean a large amount of information about the patient they’re about to see, just by going into the electronic medical record.”

The advent of the electronic medical record has radically changed how physicians take a patient’s medical history. The new systems give doctors access to a sometimes inordinate amount of information that often contains notes and test results from many different institutions. But the system is far from perfect. It can disincentivize providers from taking their own patient histories as thoroughly when so much data can already be found in a patient’s chart, and the problem is that this information is not always accurate. That being said, the ability to see most of a patient’s records in one place is highly advantageous, particularly in situations where a patient is nonverbal or struggles with dementia or is otherwise a poor narrator.

In regards to relying on imaging for basic procedures, Chan said that if as a doctor “you don’t know your anatomy, ultrasound is really not going to help you that much.”

“It’s not like the two things are divorced from each other, where either you have ultrasound or you know how to do a physical exam,” Chan continued, “you kind of have to know both.”

That being said, many of medicine’s basic procedures—like inserting a central line—are only taught to residents when imaging is used to guide the way. In our current system, if ultrasounds were not available, it would be impossible for today’s US doctors to insert central lines and chest tubes or perform arterial blood gases and lumbar punctures. Chan assured me that an ultrasound machine is a very basic tool; there is virtually no place where this technology cannot be obtained in the US.

While the integration of technology into medical education makes sense to me, I asked why we cannot still train our doctors to learn how to perform these procedures without imaging, too. Knowing how to insert a central line or chest tube without imaging won’t change the way physicians do these procedures when an ultrasound machine is around, but the skill of doing certain procedures based on anatomical expertise would be preserved. And being more comfortable with this foundational knowledge may have significant long-term benefits that are less easily quantifiable. “There could certainly be value in that…[but] it’s always a matter of what’s something that every single internal medicine physician should know,” Chan said. She explained that it might be worthwhile to invest that type of training into physicians who will be working in unconventional environments, but that those who will be practicing in a hospital will not really have need for those skills.

But what about doctors who work in unconventional environments—or at the very least in smaller and under-resourced ones? Guilherme Henrique Da Silva Goes, a fifth-year medical student in Manaus, Brazil, told me that patients at his hospital sometimes die because of a lack of medical technology. “But at the same time,” he said, “when you’re exposed to a hard environment, you end up becoming very resourceful.”

Goes described a common problem in Manaus, where one will diagnose a patient and determine the best medication to prescribe, only to find out that the medication is not available. “It’s run out, [and] we don’t know when they’re going to replenish it, so then we have to look at the other medications we do have,” said Goes. Other medications are often less than ideal: They may have more side effects, which might make a patient less willing to take them or could be harmful depending on the patient’s preexisting conditions, but being forced to pivot strengthens one’s abilities as a practitioner. “You end up having a lot more experience in collecting a good history and doing a thorough physical exam because you have to,” Goes told me. In situations that require improvisation, these foundational skills become particularly irreplaceable.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The issue of de-skilling has divided the medical community. While virtually all physicians agree that medical technology offers significant advantages, there are differing opinions over how much it will disrupt the teaching of fundamental skills, like performing a thorough physical exam or taking a comprehensive patient history. Although this phenomenon of incorporating more technology has largely occurred alongside a movement for patient safety, one study has already identified several negative outcomes with de-skilling, including decreased clinical knowledge, decreased patient trust, increased stereotyping of patients, and decreased confidence in making clinical decisions.

On the whole, relying on medical technology increases patient safety, but there are trade-offs. On the one hand, a doctor who uses all available resources in order to come to a diagnosis may identify disease more accurately or quickly, yet they also might dehumanize their patient by submitting them to a gamut of tests. What makes this particularly anxiety-provoking is the fact that this approach often leaves patients to the mercy of insurance companies. Tests are already scary, but the added uncertainty of whether they’ll be covered raises the financial stakes. Meanwhile, the doctor who relies on a learned relationship with the intimacies of their patients’ conditions can inspire more trust, lessen anxiety, and contribute to better emotional well-being. And given the myriad of research linking mental and emotional health with physical health, a doctor who puts their patients at ease likely improves their outcomes, too.

Carvalho, who began his medical training in Brazil before completing it in the United States, describes American medical education as more systematic than its Brazilian counterpart. “In the US, the presentation, how we would discuss the cases…it was [done] in a very ritualistic manner,” Carvalho told me. “In Brazil, we were a little bit more loose.”

Carvalho argues that the US attitude toward healthcare undercuts the creativity of medicine. It can be hard to push past the procedural nature of it all and develop intuition. But that human instinct is exactly what separates a good doctor from merely a competent one. If we understand medicine primarily as caregiving, then technology, which can simplify the skill level needed to perform certain medical procedures, will never fully replace the creativity, sensitivity, and empathy required for building trust, and thereby relationships, with patients. “I think that’s a real fear, and it’s a healthy fear,” Chan explained, “but as we’re taking advantage of all the benefits that technology is providing, a big piece of it still has to be that connection between the physician and the patient.”

The way someone looks at you, the intonation in their voice, and the many other very human clues that patients convey are exactly why technology can never replace physician intuition. Carvalho’s past experiences prove this to be the case: Recall the patient in Ann Arbor, who likely would have been misdiagnosed with pneumonia were it not for Carvalho’s insistence on speaking to the family. While the United States often pushes a rote test-forward approach to medicine, it’s these sort of creative solutions alongside more traditional medical interventions that often end up giving the patients the care they need. Traditionally, the development of a doctor’s intuition has been hard earned by learning on the job. Experience should not be wholly undercut by technology, or somewhere along the way, we might lose the art of medicine to the science of it.

More from The Nation

In the GOP Civil War Over Immigration, Both Sides Are Racists In the GOP Civil War Over Immigration, Both Sides Are Racists

Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy want cheap labor—not a multiracial democracy.

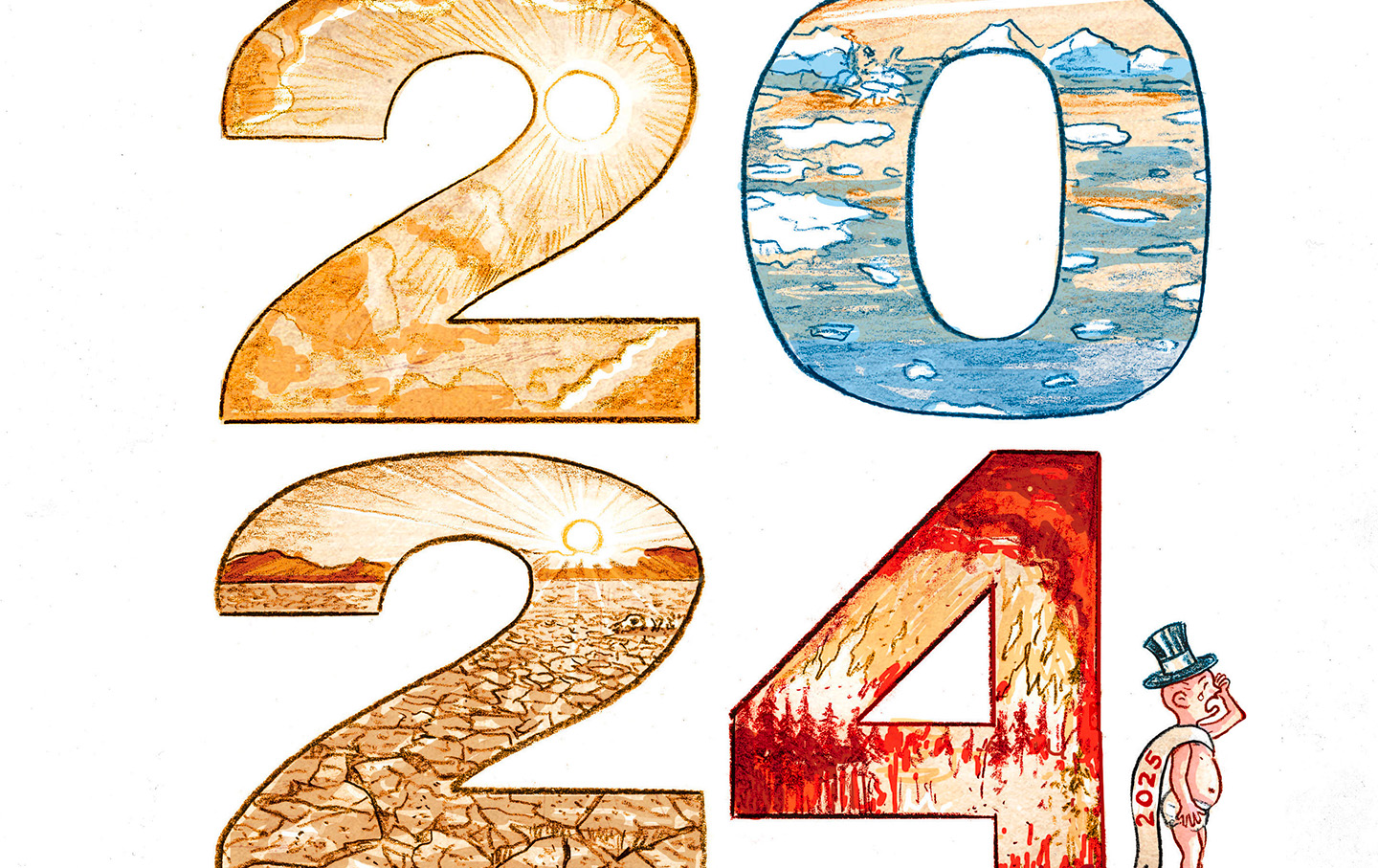

2024: Hottest Year on Record 2024: Hottest Year on Record

What will 2025 bring?

President Biden Should Pardon Ethel Rosenberg President Biden Should Pardon Ethel Rosenberg

A newly released classified document shows that the National Security Agency knew Ethel Rosenberg was not a spy—and that the government executed her anyway.

Blake Lively’s Suit Exposes the Twisted World of Hollywood Misogyny Blake Lively’s Suit Exposes the Twisted World of Hollywood Misogyny

The complaint revisits the same gaslighting tactics in the Amber Heard case, and has produced much the same social media fallout.

The Drama and Suffering of the World Chess Championship The Drama and Suffering of the World Chess Championship

A dispatch from the pivotal Game 11 in Singapore that helped make Gukesh Dommaraju an 18-year-old chess champion.

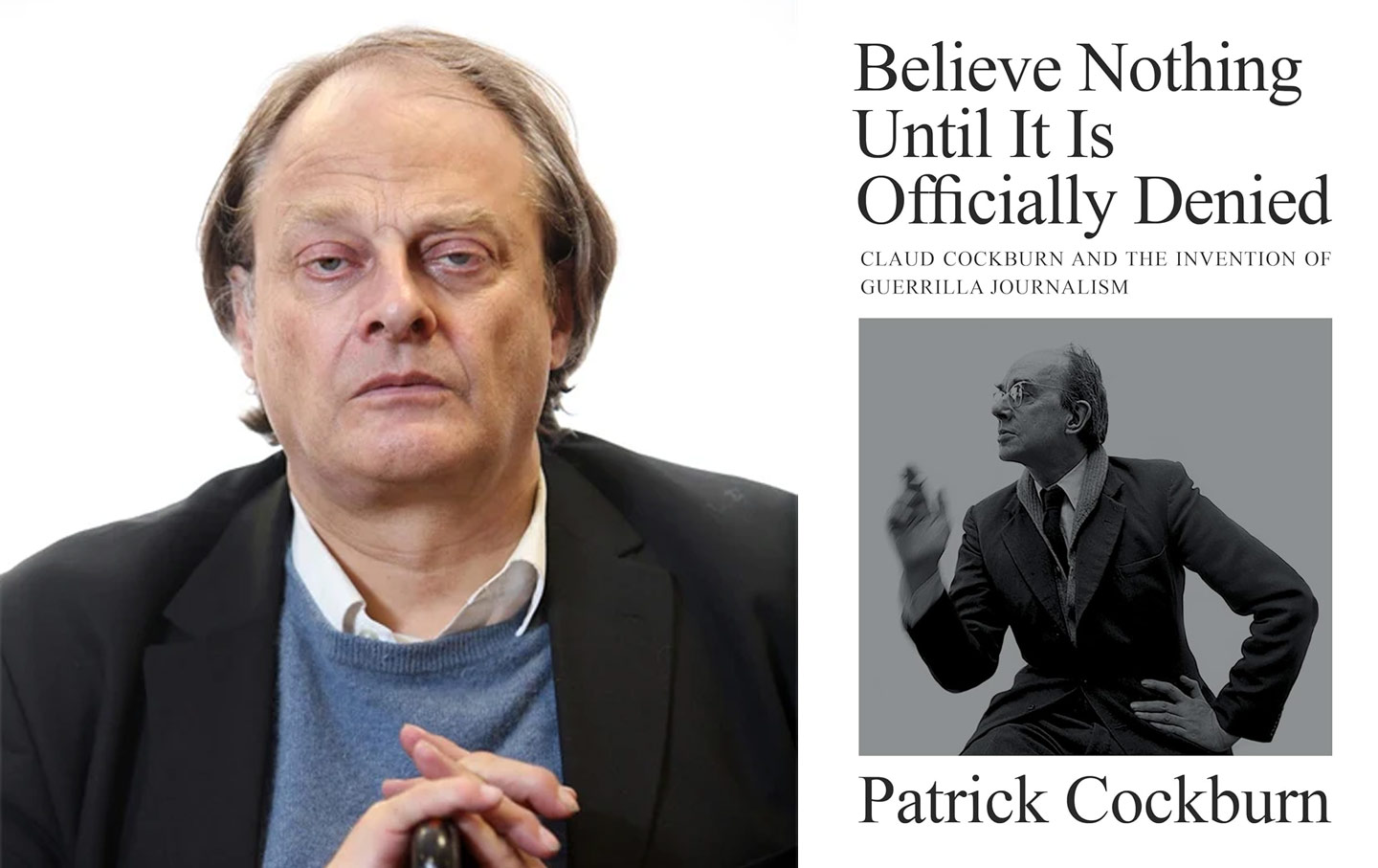

Claud Cockburn’s Legacy of Guerrilla Journalism Claud Cockburn’s Legacy of Guerrilla Journalism

Patrick Cockburn discusses his new biography about his father, Claud, with his niece, Laura Flanders.