Adam Ehrlich Sachs’s Exhibitions of Absurdity

In Gretel and the Great War, an antic epistolary novel set in early 20th-century Austria, the writer tries to make sense of a society gone mad.

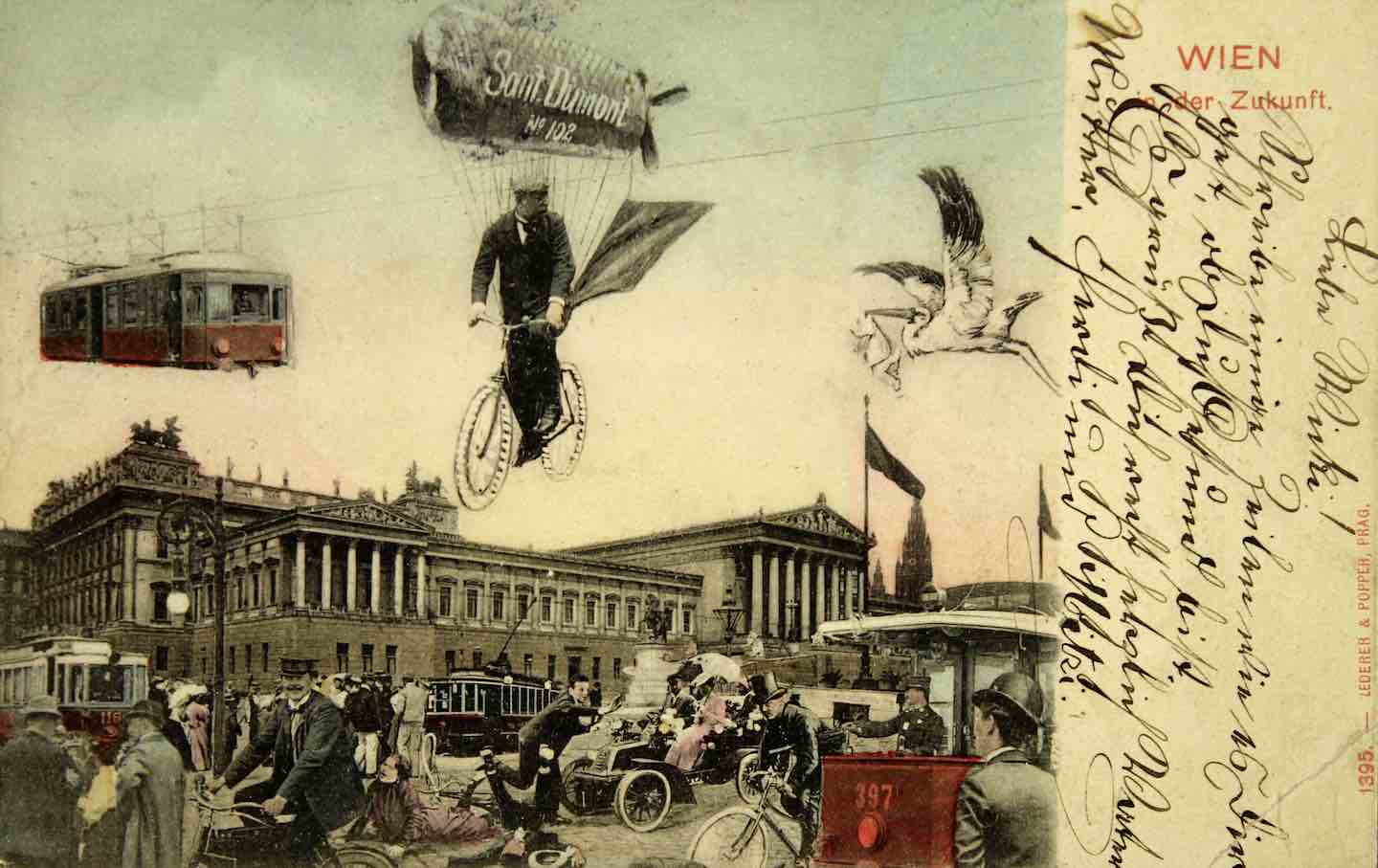

A postcard depicting Vienna in the future, 1905.

(Anonym / Imagno via Getty Images)

“We are obliged to regard many of our original minds as crazy,” wrote Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, the 18th-century German scientist and aphorist, “at least until we have become as clever as they are.” The characters that haunt Adam Ehrlich Sachs’s fiction—the blind astronomer who predicts an eclipse, the architect who designs buildings of scandalous simplicity, the physiologist who aims “to renew language by removing its encrustations”—possess minds that Lichtenberg might have deemed “original.” They exhibit qualities of both genius and madness, and Sachs’s fiction finds a home in the unmappable boundary between them. His geniuses lack a sense of proportion and live lives of devout eccentricity. It’s fitting, then, that his second novel, Gretel and the Great War—narrated by an institutionalized playwright—should be a work of comic and inventive excess, a wonderfully disproportionate book that eschews the familiar and stultifying comforts of moderation. In its imbalanced way, the novel becomes the perfect vessel to carry and satirize the post-rational ideas of a self-obsessed society.

Books in review

Gretel and the Great War

Buy this bookGretel and the Great War is framed as a found text comprising a series of letters. A brief preamble provides context: The year is 1919, and a mute girl turns up on the streets of Vienna. She is “handed over to the care of a neurologist,” who reasons that her silence is due to “a childhood deprived of language.” When he appeals to the public for information, the lone response comes from a patient at the Sanatorium Dr. Krakauer. The girl’s name is Gretel, the patient writes, and she’s not mute at all. Claiming to be her father, the patient says she grew up in a home rich with language and story. He sends Gretel 26 bedtime stories, one for each letter of the alphabet. Does someone read the stories to her? Do they bring Gretel comfort at night? All we learn is that the stories fail to make the cut for Dr. Hans Prinzhorn’s anthology of the art of the mad: “Evidently Prinzhorn found them unsuitable; they turned up in his archives some eighty years later.”

Sachs’s previous novel, The Organs of Sense, undercut itself in a similar fashion. Its narrator, the 17th-century philosopher Gottfried Leibniz, sends a record of his strange encounter with a blind astronomer to a journal called Philosophical Transactions, though the report is “for some reason never published there.” Narrative layers can coat a work in synthetic importance, a needy ploy to be taken seriously. By presenting texts as found and rejected, though, Sachs endearingly self-deprecates, disrupting the staging that makes some literary fiction prone to postmodern stuffiness. Sachs’s work wields a double edge—one side, the sharp confidence of invention; the other, the self-lacerating shame of artmaking. “I feel like a writer should never get over how embarrassing this is,” he once said in an interview. Gretel, then, is an exhibition of human absurdity, further enriched by its urge to implicate itself as a ludicrous act. Sachs would admit himself to the Sanatorium Dr. Krakauer, if only he felt he had earned it.

The 26 stories forming the book are letters to Gretel, each representing a character. As bedtime stories, their worth is questionable at best—but as curios of fiction, they’re rare antiques, finely crafted toys. The ballet master (B) strives to return dance to the pre-Baroque, even the pre-pre-Baroque; the explorer (E) dares to journey into the last of the earth’s remaining void spaces. There’s a simple architecture to these stories: A character nurtures a peculiar idea and tends it until it blooms into full foolishness. When characters face indisputable evidence of error, they deny it. Sanity, moderation—these are limitations, not virtues, in this world. Sachs admires those who have discovered their raison d’être, even, or especially, if it comes at great cost to reputation and equanimity. These characters and their impenetrable subjectivities help cultivate Sachs’s brand of negative capability: the physicist who believes in his particles, the choreographer who believes in the primordial origins of dance, the immunologist who believes a disease is sweeping the city. Their misplaced faith, played for laughs, is often compelling, sometimes moving. “Even in a city celebrated for its psychological profundities, most people still have to come up with their own reasons for why they act and feel the way they do,” Sachs writes in “The Toymaker” (T). Gretel teems with those reasons and unreasons.

Several stories rely on conflicting accounts of events to create an unsettling, pleasurable parallax—none more so than “The Father” (F), in which a physiologist meets a monk and is so taken with the “skeptical, secular glint” in his eyes that he joins the monastery to discover the monk’s secret. One day, the monk hands him a newspaper clipping that contains the testimony of the monk’s daughter. The monk is actually a failed physicist, who, his daughter claims, murdered her mother by forcing her to handle a deadly substance that could prove the existence of his obsessive inquiry: “unobservable” particles. Once captured in the physicist’s elegant equation, the particles revealed “the hidden substructure of all real and theoretical substances.” Unfortunately, the particles don’t exist. The physicist knows it, but he asks his daughter, again and again: “My particles?” Her dutiful response: “They exist, Father.” The daughter, like many other characters, is committed to the Sanatorium Dr. Krakauer, and the mother, only half-dead, ends up in a later story. To the Sachsian character, hoeing the tough row of the preposterous project, a child is an obliging validator. A parent, like a writer, is a credible fraud.

With Gretel, Sachs seems to draw inspiration from The Voice Imitator, Thomas Bernhard’s jaundiced version of Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. Pasted together from news reports and idle talk, The Voice Imitator bitterly, casually, and comically observes the ruin of its various characters. Sachs doesn’t aspire to Bernhard’s bile, though, and his work, to its credit, has a peculiar gentleness. While he shares Bernhard’s interest in the manic mind, Sachs’s stories bloom in moments of odd specificity based less in character than in language. He takes great pleasure in language—not as a lyrical hedonist prone to pile on words, but in precise, surgical acts of locution. The constrictions of story logic funnel the prose into unlikely arrangements, phrasal punch lines. From “The Kindergarten Teacher” (K): “The sound of her celebrated sister’s skull striking the edge of the kettledrum is described so vividly in the morning paper that she can hear it reverberating in her own head.” Or from “The Obstetrician” (O): “They innocently inquire about the ethnic significance of his hat.” As rules accrue, Sachs diligently follows their sequence to consequential yet delightfully unexpected outcomes of diction and syntax.

Gretel rehabilitates the exclamation, and Sachs applies it with a flair characteristic of the works of Gert Hofmann, particularly Lichtenberg and the Little Flower Girl, which might also have lent him the idea for the frequent line breaks and slippery, indirect speech. “An exclamation point is like laughing at your own joke,” said F. Scott Fitzgerald, something Gretel’s narcissistic father is more than capable of. (He ends nearly every story with an exclamatory “Good night!” or “I kiss you good night!”) But Sachs’s exclamations don’t ring with authorial self-satisfaction. His marks (and comma splices) backdate the prose and give it the desired texture of German in translation—another joke toward the book’s implausible, half-explained origins, and an homage to Bernhard and Hofmann. More than anything else, the eccentric punctuation deepens the themes. In “The General Intendant’s Daughter” (G), the famous actress Klamt begins a feud with the general intendant, who has cast his own daughter in the lead role. Klamt recognizes the general intendant as the former ballet master (B), who either crippled or killed his wife with his choreographic demands:

He impaired his wife with dance! Slew with an undanceable dance! A dance no one could dance! So first of all they were taking their dramaturgical guidance from someone who had zero formal training in theater! And who murdered his wife through choreography! This in the opinion of the finest physicians!

Emphasis turns into zeal and its funny but uninhibited cousin, fanaticism. In search of protection against reason, Sachs’s characters—frightening, frightened—deploy the exclamation to buttress the untenable position.

Twenty-six is a lot of letters, though, and the proof of concept almost proves tedious. Gretel’s conceit demands regular reinvention, a scheduled reset. Sachs’s comic virtuosity, like much virtuosity, has a sort of athletic repetitiveness, a muscular monotony. His discipline teeters on the edge of overcommitment to the bit. Yet the too-much-ness of Gretel is partly the point: the book’s reflection of the decadent society that refuses to look at or learn from itself, and the author’s strict fidelity to style and conceit. Fortunately, the back half of the novel is heavier, darker, and governed by the disquieting mood of fairy tale—a welcome tonal shift after the comic extravagance in Sachs’s default mode of droll baroque.

Although Sachs rearranges the details of the stories, the predominant themes persist—none more so than parenthood, the ur-theme uniting and contextualizing every tale of madness, genius, blindness, silence, obsession, and doom. Gretel’s parents are loving but catastrophically distracted, well-meaning but hopeless. The children are pawns in power struggles, collateral damage. In Gretel, F is for “The Father” and M is for “The Mother,” as if they’re disciplines of study, skilled vocations. Like an architect or scientist or painter, a parent can bungle the job with the right investment of myopic obsession. By the logic of the book, a parent is a kind of Sachsian genius, a paragon of misguided devotion, ready to drive off the edge of reason. Etymologically, “genius” conjures an external spirit that attends one at birth, a guardian deity. However far from gods, parents are often present from the beginning—attending, supposedly guarding. Sachs understands genius as a kind of parenthood, the rearing of a small and vulnerable thing. Hope is its hazard. At the end, Z is for “The Zionist,” and he turns out to be our narrator, father of Gretel and an ill-conceived dream: “the Jewish State, to which he himself gave birth during an evening at the theater.” He is our genius, our parent: He created the world we’ve inhabited for 200 pages, but then he’s taken away. We end where we started, with a father reaching out, his love failing to find its object. What is his genius worth now? He and his stories rescue no one.

Sachs’s fascination with eccentric artists and thinkers illuminates what he values most in writing: aesthetic courage, individual style. Gretel possesses both. Like Sachs’s characters, the novel moves toward extremity, seeking the terminal point of comedy and constraint. Rather than look for ways to soften or sand down these excesses, Sachs has doubled down on the hallmarks of his fiction—macabre slapstick, generous satire, treacherous parenting. But his successes leave him a somewhat solitary talent in American fiction. I suspect he recognizes this. In “The Neurologist” (N), he seems to steal a glance at himself in the mirror:

Actually no one can figure out exactly which field the neurologist is working in. The psychopathology journals consider his paper too preoccupied with ethical prescription, the ethics journals consider it too ornithological, the ornithology journals consider it too psychopathological.

In the end, he puts the paper in a drawer. Publication, he realizes, is not the point. The point is not publication but rather the liberation of a spirit from the vessel in which it is trapped.

Is Sachs describing himself, a writer who has shown little interest in making work that succumbs to market trends? No—he’s describing the neurologist, who subsequently saws through the neck of a heron to release the trapped spirit of his love. But could he also be describing himself? Sachs’s fiction has a spirit, one that he seems loath to trap in contemporary fiction’s familiar vessels. An air of self-imposed obscurity clings to his work, as if the quests of rejection and failure he depicts are enviable career trajectories. Sadly, he is already too successful; true Sachsian genius evades his grasp. Let him settle for what he’s achieved: a small and nearly peerless place in literature. Perhaps we should file his work under P, and pray that publication continues—even though it’s far from his point.