Damascus Diary: A New Year in a New Syria

Syrians begin to learn to live without Assad.

Damascus and Sednaya, Syria—On New Year’s Day, Diyya ad-Din Dereh took his family on an outing. He, his wife, and their four young girls squeezed into their silver Kia sedan and headed to Sednaya Prison, in the foothills of the Qalamoun Mountains. Dereh, a tailor from Damascus, had been arrested in 2011 as protests erupted against Syria’s dictator, Bashar al-Assad. His brother, a student, was also captured that same year, and ended up in Sednaya, a prison that was known as the “human slaughterhouse,” a place where Assad’s officers inflicted sadistic torture on inmates.

On December 8 last year, Assad fled Syria, and rebels took control of the state apparatus. They flung open the doors of prisons and killed the handful of regime loyalists who had remained. When the rebels deemed it safe, the families of the missing were allowed to search the premises.

I visited Sednaya just over three weeks after Assad’s departure. Deep holes had been gouged in the floor by rescue groups and relatives who had been searching for loved ones thought to be in a rumored underground facility. A stern delegation from Germany was being taken on a tour by the White Helmets, a civil defense group that had been helping to try to locate the underground prison. Over 100,000 people are estimated to have been disappeared by the Assad regime. Many of the country’s Sunnis believe that the dictator and his backers subjected their population to a genocide.

The Sednaya complex was the most infamous of Assad’s prisons, and had become symbolic of his brutality. People had plastered the prison with the pictures of missing people. Discarded clothes cluttered cell rooms, where up to 50 inmates were held at a time. The place was rank with the smell of rotting bodies, the stench of pain and desperation.

Dereh, who was released by Assad and fled to a rebel-controlled province, knew he would not find his brother. After four years in jail, all traces of his brother had disappeared. “I wanted to show my children where their uncle was killed,” he told me. “I want them to understand what happened.”

To get to Syria, I had flown to Beirut. In the city’s southern suburbs, I passed buildings that had been shattered by Israeli bombs, and into the snow-dusted peaks of the Anti-Lebanon Mountains. At the Masnaa border, the car jolted on the road. My driver explained that an Israeli air strike in October had cratered the tarmac.

Israel’s bombing campaign in Lebanon this fall killed most senior leaders of Hezbollah. Assad, who had relied on the group’s fighters in the past to stay in power, was left exposed when Hezbollah and Israel signed a ceasefire in late November. (Israeli government sources claimed that Hezbollah, the Lebanese Shia militant group, was using the road to ferry weapons into the country to attack northern Israel.) “After the ceasefire,” my driver pointed out, “the Lebanese repaired the road immediately.”

At the border, our headlamps swept across billboards of Assad that had been torn to shreds by Syria’s new rulers. Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, or HTS, a rebel group with roots in a Sunni jihadist organization, had swept into Damascus on December 7, and Assad flew out of the country, arriving in Moscow, where he was given asylum. The rebels now manned the border post, long hair and shaggy beards poking out of their balaclavas. With barely a glimpse at my passport, we were waved through and onto a murky road with extinguished streetlamps.

After about 45 minutes, we saw turnoffs marked with the names of Damascus neighborhoods. The city’s suburbs had barely any lighting, so all of a sudden we were in the center of town, turning past masked men who had been rebel fighters only a few weeks beforehand. On traffic islands, people set off fireworks and draped themselves in the new Syrian flag, green and black and white, with red stars.

When I asked Syrians in Damascus what they thought of Assad’s fall, they invariably replied that it was “like a dream.” Theories abounded as to why a dictator who projected an image of strength fell so rapidly—was it because the generals who supported him were not being paid enough? Because his army was shattered and exhausted after 11 years of civil war? Because some concatenation of plots by foreign powers (the United States, Israel, Turkey) had neutralized one of Iran’s most important allies? Or was it because, as I was told over coffee at a hotel festooned with hanging vines and bearded militants using the WiFi, Assad had finally decided to take revenge on the Syrian people for betraying him? Nobody had a clear idea: All they could tell you was that a second act for the dictator was out of the question, even as they worried about what the future would bring.

For now, HTS has slotted itself into the spaces left by Assad’s fleeing men. They have taken over police stations, ministries, and military bases. When I visited Assad’s Ministry of Information, a skyscraper with richly cobwebbed stairwells and a rattletrap elevator, workers were screwing billboards with a new logo into the lobby walls. Men with the accents of rebel provinces sat behind large desks and hosted long meetings on how to best deal with the influx of foreign media, which interviews to grant and which not; in the process, they ended up saying very little, because no one knows who has and who does not have the authorization to speak to foreigners.

On the streets, the HTS fighters had become policemen, stern but silent, occasionally mugging for photos with children and letting smiling women pose with their Kalashnikovs. On December 31, HTS men jostled to get a good viewing spot as an historical drama about an Arab rebellion against the Ottoman occupation of Syria was being filmed in front of the Mausoleum of Saladin, complete with actors in period uniforms.

That afternoon, shopkeepers did frenzied business, and there was a sense of relief, the shrugging off of a great weight, even as everyone worried about what is to come. Amir, a fabric seller in the historic Old City, told me he gladly accepted dollars, unthinkable under Assad’s rule. “For just holding one dollar, I could have gone to jail a few weeks ago,” he said.

Syrians hope the United States will lift sanctions against the country, sparking a boom in business, but such actions may take some time, as HTS is designated both by Washington and the UN as a terrorist group and president-elect Donald Trump has indicated that he wants little to do with Syria. Only Turkish construction companies have signaled that they are keen to do business with the new regime.

As 2025 was rung in, the Old City filled with crowds of people who danced and sang. Fighters fired red tracer rounds into the air and young men fired bottle rockets. Speakers blared “Lift Your Head Up, You Are a Free Syrian,” an anthem of the revolt against Assad, and songs by Abdul Baset al-Sarout, a singer who died in combat with Assad’s forces in 2019. In bars, men drank alcohol and danced with other men and women: Fears that HTS would apply the strict Islamic law that they had imposed in areas they governed in the north had not yet come to pass.

Sednaya is not only a prison. The nearby town is home to a convent that is among the oldest in Christianity. Legend traces it back to the Byzantine emperor Justinian. Perched atop a rock, the regime’s jail is visible in the distance, but residents of the town told me they had nothing to do with the facility: Its officers lived on the base. Residents, afraid of informers, would not talk about it, even though it loomed on the main road. When driving, they would speed past its concrete barricades so as not to invite trouble. “It was a great injustice the Assad regime committed, naming the prison ‘Sednaya,’” a senior member of a Christian self-defense group in the town told me. (He requested that I not use his name or image because he was negotiating with the new authority.) “Now we are worried that people will take revenge on the town, even though we had nothing to do with the prison.”

Assad made much of his protection of Syria’s minorities, but the regime also knew how to play different groups off against one another to maintain power. Syria is intensely sectarian. Local self-defense groups sprang up to protect areas with large concentrations of minorities. Sednaya had been attacked before: In 2013, the monastery had even been hit during shelling. Christians there told me that the Russians afforded Syria’s Christians some degree of protection and built a statue of the Virgin Mary on a nearby peak, but that they had increasingly been left alone. “The regime’s hands were full of blood,” the defender told me. “People in Sednaya were afraid, and the Christians had to defend themselves.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Now the town’s defenders had to deal with new rulers: HTS. A banner with the new Syrian flag had been affixed to the front stair of the monastery. The group had tried to enter the church, but the defense force had told them not to do so. They saw it as a positive sign when HTS agreed to withdraw to a checkpoint a few hundred meters down the road.

Ahmed al-Sharaa, the rebel commander who is now the de facto head of government in Damascus, has signaled that he is open to the inclusion of minorities in the new Syria and recently met with church leaders. But in early January, liberal Syrians said they were concerned that a new school curriculum announced in the last few days is overly Islamist, and shows the government’s true agenda, and people were concerned by clashes between Sunni and Christian farmers in the nearby town of Maaloula. Damascenes I spoke to were particularly concerned that al-Sharaa’s government had said that elections might take up to four years.

On New Year’s Day, Dereh, the tailor whose brother had disappeared in the prison, told me that he was “hopeful for the future, now that the bad man has gone.” Other Syrians, especially those from minorities, were less sure. Aziz and Michline had come to the monastery from Damascus to celebrate New Year’s Day with their two children. They were trying to remain optimistic, but they hadn’t visited their friends the previous evening, as they traditionally would have—they were worried that the streets would be dangerous and unpoliced. (Weapons, abandoned by Assad’s men, are extremely cheap on the black market, and minority groups are arming self-protection forces.) Their 16-year-old daughter, Jessica, had taught herself fluent English during the war by watching American movies and YouTube. She dreamed of studying abroad. “Whatever you study, whatever degree you get, it’s useless outside, so if we just study abroad from the first place, it’s better,” she said. “My friends, they all think about leaving Syria.”

The defender in Sednaya town told me that he hoped European powers would guarantee the safety of Syria’s minorities, but that he didn’t want to take any chances. The nuns at the convent had been forbidden to speak on the record by the Orthodox patriarchate of Antioch, but their attitude was one of stoicism: Each epoch brings its challenges, but they would remain, as their forebears had done for almost 15 centuries.

Syria, though, has been irrevocably changed. Heading back into Damascus from Sednaya, we took a detour through Jobar and into the eastern suburbs of the capital. Assad leveled the area, which was an opposition stronghold, in 2017 with bombs and shells. Rows and rows of skeletal buildings stretched for miles. As dusk settled, men huddled in the ruins around fires for warmth. We drove for half an hour, an hour, and ruined buildings stretched as far as the eye could see.

More from The Nation

This Is Not Solidarity. It Is Predation. This Is Not Solidarity. It Is Predation.

The Iranian people are caught between severe domestic repression and external powers that exploit their suffering.

How a French City Kept Its Soccer Team Working Class How a French City Kept Its Soccer Team Working Class

Olympique de Marseille shows that if fans organize, a team can fight racism, keep its matches affordable, and maintain a deep connection to the city.

Donald Trump’s Nuclear Delusions Donald Trump’s Nuclear Delusions

The president wants to resume nuclear testing. Senator Edward Markey asks, “Is he a warmonger or just an idiot?’

The Colonial Takeover of Venezuela Begins with Corporate Investment The Colonial Takeover of Venezuela Begins with Corporate Investment

The spectacle of Nicolás Maduro’s capture has drawn attention away from the quieter imposition of systems and power networks that constitute colonial rule.

The US’s Nuclear Arms Treaty With Russia Is About to Lapse. What Happens Next? The US’s Nuclear Arms Treaty With Russia Is About to Lapse. What Happens Next?

If the US abandons New START, say goodbye to that comfortable feeling we once enjoyed of relative freedom from an imminent nuclear holocaust.

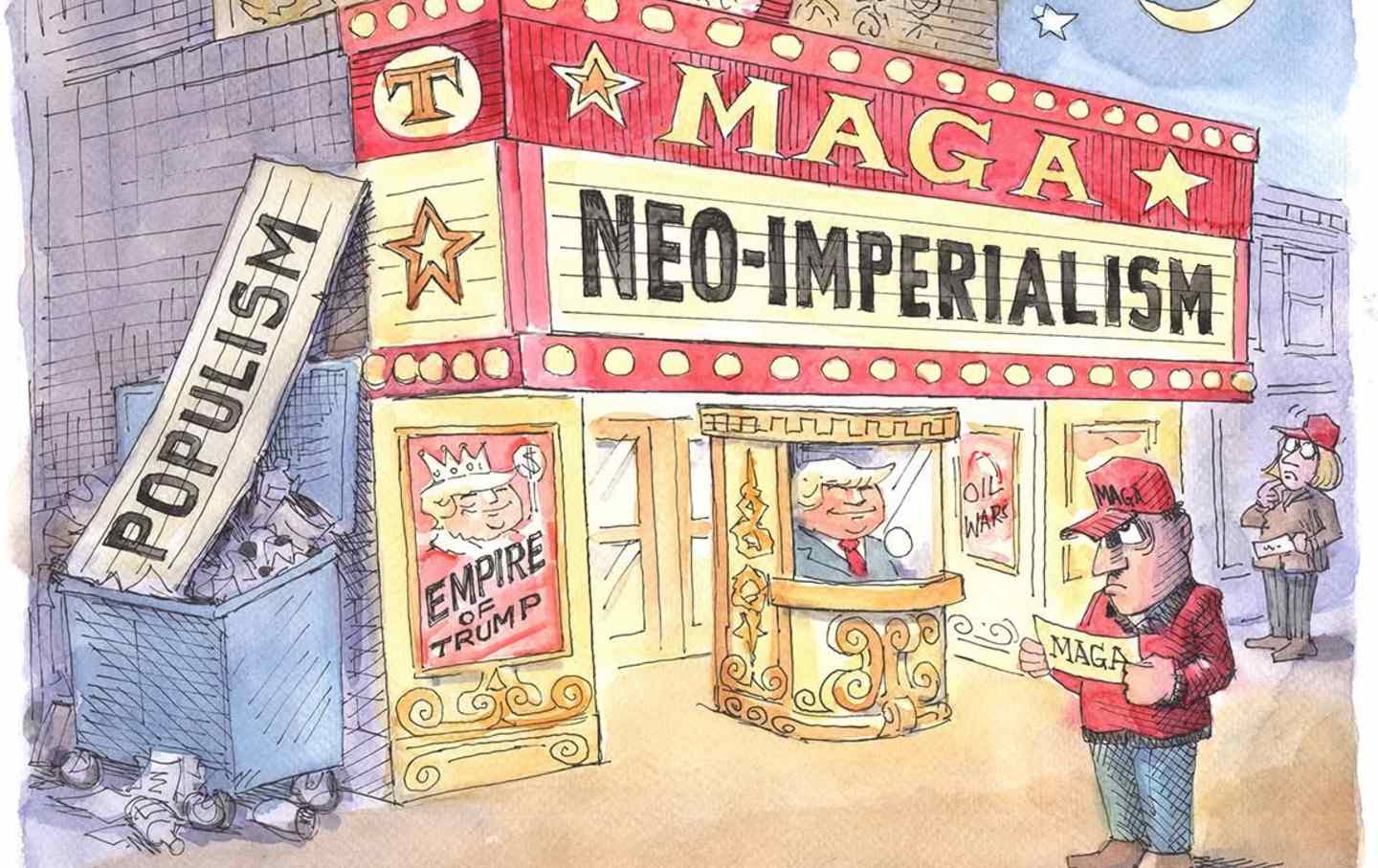

Trump’s Predatory Danger to Latin America Trump’s Predatory Danger to Latin America

The United States is now a superpower predator on the prowl in its “backyard.”